Privacy Preserving Federated Learning on a Deep Neural Network

Groundbreaking developments in medicine, economics, etc. are taking place everyday due to the field of machine learning. However, rarely is the data truly protected. The modern paradigm in data science and machine learning is to aggregate everyone's sensitive data in a data center and protect it behind a layer of encryption. This, however, has been shown to be an unsafe practice; as shown in major data leaks by Apple, Equifax, and many more. A potential solution is to allow users to retain their data locally and protect it locally, while still retaining the ability for learning models to be developed using this data. Federated Learning is a recent advance in privacy protection and is a real solution to this issue. This technology is a means to train a shared model by aggregating and averaging locally-computed updates while the sensitive training data remains distributed locally across many parties. This project is a proof of concept for federated learning of deep networks based on iterative model averaging on a chosen dataset, MNIST data set. However, this learning method is vulnerable to a set of attacks, which could originate from any party contributing during federated optimization. In such an attack, a client's contribution and information about their data set is revealed through analyzing the distributed model. I plan on protecting against this by implementing a set of privacy preserving measures to ensure that this sensitive data is protected against adversarial parties during training. The aim is also to balance the trade-off between privacy loss and model performance.

In this project I set out to train a deep neural network using the MNIST data set distributed between multiple parties while maintaining privacy for each user. The primary method I intend on using is federated learning. This method of machine learning is designed to act on data stores that are held locally across many parties which is perfect for my task.

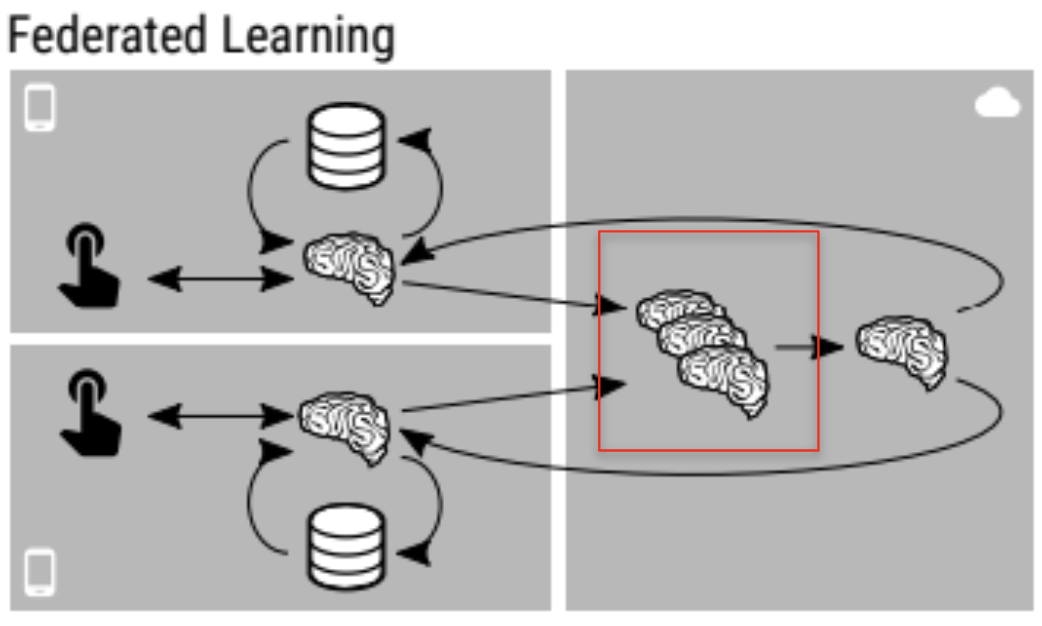

Federated learning, inherently, is more secure than standard traditional learning methods as it does not require centralizing data on one machine or in a data center. This method allows many parties to collaboratively train a shared prediction model while keeping all the training data local to each party's machine. This learning method was created by Google to train models on data stored locally across android mobile devices. It works by first downloading the current model, improves it by learning from local data, and then summarizes the changes as a small focused update. This update to the model is then sent to a third party in an encrypted form and is averaged with other user updates to improve the shared model [Research:Federated].

According to H. B. McMahan, et al. federated learning is designed to train from real world data on mobile devices, train on sensitive or large data sets, and to perform supervised learning on data that can be inferred naturally from user interaction [McMahan:Federated]. A great example of this is image classification, as it is real world data that can contain sensitive information and can be easily labeled with slight user interaction or meta-data.

Skin cancer image classification is a significant problem being solved with deep learning and convolutional neural networks [Esteva:Dermatologist]. Researchers at Stanford were presented with a data set of 130,000 clinical images. This enabled them to create an image analysis application running in a mobile environment that can classify skin lesions to hopefully predict skin cancer from a single image. This technology is undoubtedly significant, however; using a dataset can present researchers with a set of issues. Generally speaking, limited access to secure data can prevent the learning model from increasing in accuracy over time. Creating a bottle-neck in the training pipeline.

This is an excellent example of image classification that solves a problem plaguing millions of people worldwide that is only as accurate as the training set allows it to be. By training with federated learning you would be able to continually train the model as users use the model, and overtime potentially achieve the theoretical limit of predicting and classifying different forms of skin cancer. All while preventing the user's data from ever leaving their phone and maintaining a high level of privacy for a data sensitive image.

While there is a natural predisposition to privacy with federated learning, due to a user's data never being sent from device. It is still incredibly necessary to encrypt the model update prior to sending it from the users device to the trusted third party. In the event that an adversary is able to access the current state of the model and access the optimization update sent from a party's device, it is possible that the adversary would be able to infer the sensitive local data without ever having access to it. In order to protect against this the update needs to be encrypted prior to being uploaded into the third party's possession.

Utilizing a form of differential privacy or homomorphic encryption has been utilized for some studies [Geyer:Differentially, McMahan:Federated, Nabi:Privacy] with success, lending me to believe that this level of privacy should be sufficient in preventing adversaries.

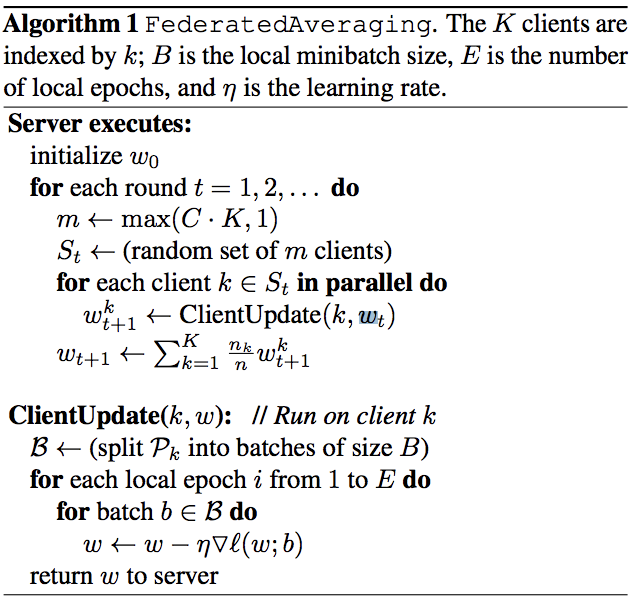

In this federated learning proof of concept, I attempted to adhere to the structure of federated learning designed by Google's team [Research:Federated] while attempting to implement a federated averaging algorithm set up by McMahan's group [McMahan:Federated].

In this proof of concept I decided to take an iterative approach. I first set out to perform linear regression on the MNIST dataset, to establish a baseline model. Then I set out to perform a 2-party federated learning example, once this was achieved I performed the 2-party case 4 more times to attempt to simulate a 6-party federated learning simulation.

In order to utilize the MNIST dataset, I had to load the entire dataset into memory. This was done using the defined load_mnist function, and in order to appropriately distribute the MNIST data into all 6 parties I chose 6 different sets of data from the MNIST training and testing sets.

def load_mnist(imagefile, labelfile):

# Open the images with gzip in read binary mode

images = open(imagefile, 'rb')

labels = open(labelfile, 'rb')

# Get metadata for images

images.read(4) # skip the magic_number

number_of_images = images.read(4)

number_of_images = unpack('>I', number_of_images)[0]

rows = images.read(4)

rows = unpack('>I', rows)[0]

cols = images.read(4)

cols = unpack('>I', cols)[0]

# Get metadata for labels

labels.read(4)

N = labels.read(4)

N = unpack('>I', N)[0]

# Get data

x = np.zeros((N, rows*cols), dtype=np.uint8) # Initialize numpy array

y = np.zeros(N, dtype=np.uint8) # Initialize numpy array

for i in range(N):

for j in range(rows*cols):

tmp_pixel = images.read(1) # Just a single byte

tmp_pixel = unpack('>B', tmp_pixel)[0]

x[i][j] = tmp_pixel

tmp_label = labels.read(1)

y[i] = unpack('>B', tmp_label)[0]

images.close()

labels.close()

return (x, y)For each of the parties I randomly selected a dataset size; for party 0 I used 1,200 data points, party 1 I used 30,000 data points, party 2 I used 3,000 data points, party 3 I used 1,200 data points, party 4 I used 12,000 data points, and party 4 I used 300 data points.

These values were chosen randomly to distribute the dataset amongst the parties in order to simulate a real scenario where some users contain many points and others less. This emulation would demonstrate how my implementation fares when testes on real data.

Once the data was loaded and distributed I began my primary objective, to perform linear regression on the MNIST dataset.

classifier_lr_base_t0 = time.time()

classifier_lr_base = LogisticRegression(random_state = 0, solver = 'lbfgs')

classifier_lr_base_t1 = time.time()

classifier_lr_base.fit(train_img, train_lbl)

classifier_lr_base_t2 = time.time()This code was able to instantiate a logistic regression classification model and then fit the model with the entire MNIST training set, 60,000 points.

After this goal was achieved I set out to implement the 2-party federated learning model.

This was done by first defining a initial party to play the part of the cloud. I assigned party 0 to take this place, as it contained a minimal amount of data points and thus would have a relatively weak model attached to it.

As this is the cloud party, it would be the system which seeds the model into the memory of all other parties. The first step in federated learning is for the cloud to train on the available data held in the cloud servers. This was performed the same way that the logistic regression classifier was trained in the baseline example.

Now in order for the cloud's data to be protected the logistic regression classifier model needs to be encrypted. I chose to encrypt the model's weights and biases using homomorphic encryption.

def generate_keypair(n_length = 512):

public_key, private_key = paillier.generate_paillier_keypair(n_length)

return public_key, private_keyBy utilizing the PHE python library, I was able to generate a set of public and private keys as shown in the generate_keypair code definition block.

As the cloud, party 0, never sends any information other than the base untrained model and the encrypted model's weights and biases. Preventing the other parties from deducing the initial data used to train this model, thus protecting the data stored on the cloud's servers.

classifier_lr_0_t4 = time.time()

coef_weight_0 = classifier_lr_0.coef_[0]

coef_bias_0 = classifier_lr_0.coef_[1]

coef_weight_encrypt_0 = []

coef_bias_encrypt_0 = []

for value in coef_weight_0:

coef_weight_encrypt_0.append(

public_key_0.encrypt(value, precision=7))

for value in coef_bias_0:

coef_bias_encrypt_0.append(

public_key_0.encrypt(value, precision=7))

coef_weight_encrypt_0 = np.asarray(coef_weight_encrypt_0)

coef_bias_encrypt_0 = np.asarray(coef_bias_encrypt_0)

classifier_lr_0_t5 = time.time()This method of encryption is easily performed by isolating the weight and bias matrices, looping through each value contained in each respective matrix, and encrypting that value using the public key.

After the cloud's model's weight and bias matrices are encrypted they are sent to the non-cloud parties.

These parties each contain their own respective data sets and after being sent the untrained model are able to their own respective models. This allows all parties to generate their own set of weight and bias matrices.

After each party trains on their local data they receive an encrypted weight and bias matrices produced by the cloud and can add their weight and bias matrices to the encrypted weight and bias matrices. This is possible because of Paillier homomorphic encryption.

Then each party is able to divide each value in the encrypted weight and bias matrices by 2, producing an average weight and bias for each value.

classifier_lr_1_t2 = time.time()

coef_weight_1 = classifier_lr_1.coef_[0]

coef_bias_1 = classifier_lr_1.coef_[1]

coef_weight_encrypt_01 = coef_weight_1 + coef_weight_encrypt_0

coef_bias_encrypt_01 = coef_bias_1 + coef_bias_encrypt_0

coef_weight_encrypt_01_average = coef_weight_encrypt_01 / 2

coef_bias_encrypt_01_average = coef_bias_encrypt_01 / 2

classifier_lr_1_t3 = time.time()This set of average weight and bias matrices maintains its encryption and is able to be sent back to the cloud. This process demonstrates a learning method where neither party's data ever left their local machines, yet was still able to be used collaboratively in order to train a classifier.

Once these encrypted average weight and bias matrices are sent back to the cloud, party 0, the matrices can then be decrypted and applied to the initial model in order to yield new results.

coef_weight_decrypt_01 = []

coef_bias_decrypt_01 = []

for value in coef_weight_encrypt_01_average:

coef_weight_decrypt_01.append(

private_key_0.decrypt(value))

for value in coef_bias_encrypt_01_average:

coef_bias_decrypt_01.append(

private_key_0.decrypt(value))

coef_weight_decrypt_01 = np.asarray(coef_weight_decrypt_01)

coef_bias_decrypt_01 = np.asarray(coef_bias_decrypt_01)

classifier_lr_0.coef_[0] = coef_weight_decrypt_01

classifier_lr_0.coef_[1] = coef_bias_decrypt_01After the 2-party system was designed I set out to expand this to the n-party case.

In order to achieve this I reduced the n-party case to a 6-party case, as achieving a method of federated learning on 6 parties is in fact no different than a method of federated learning on an arbitrary count of parties.

This was performed by repeating the steps in the 2-party system, except the averaging was only performed in the cloud.

To elaborate, the cloud would train it's model and send it's untrained model and the encrypted weight and bias matrices. Then the party would train the model using their set of local data. Once this was achieved the party would then add their values to the encrypted matrices. They would then send those encrypted matrices back to the cloud.

However, at this point the could would hold n-parties' encrypted matrices, and needs to average these matrices before decrypting them and attaching them to the base model.

classifier_lr_federated_t0 = time.time()

coef_weight_encrypt_federated = coef_weight_encrypt_01 + coef_weight_encrypt_02 + coef_weight_encrypt_03 + coef_weight_encrypt_04 + coef_weight_encrypt_05

coef_bias_encrypt_federated = coef_bias_encrypt_01 + coef_bias_encrypt_02 + coef_bias_encrypt_03 + coef_bias_encrypt_04 + coef_bias_encrypt_05

federated_count = 5

coef_weight_encrypt_federated_average = coef_weight_encrypt_federated / (federated_count * 2)

coef_bias_encrypt_federated_average = coef_bias_encrypt_federated / (federated_count * 2)

classifier_lr_federated_t1 = time.time()

coef_weight_decrypt_federated = []

coef_bias_decrypt_federated = []

for value in coef_weight_encrypt_federated_average:

coef_weight_decrypt_federated.append(

private_key_0.decrypt(value))

for value in coef_bias_encrypt_federated_average:

coef_bias_decrypt_federated.append(

private_key_0.decrypt(value))

coef_weight_decrypt_federated = np.asarray(coef_weight_decrypt_federated)

coef_bias_decrypt_federated = np.asarray(coef_bias_decrypt_federated)

classifier_lr_0.coef_[0] = coef_weight_decrypt_federated

classifier_lr_0.coef_[1] = coef_bias_decrypt_federated

classifier_lr_federated_t2 = time.time()If the cloud knows how many models were received, performing the averaging is simple. The method defined takes the sum of all encrypted matrices and then divides by the total number of models received. However, this would produce an average of all the models which then need to be averaged between the values produced by the cloud and the subsequent party. So by dividing the sum by the number of models received and by 2, we are able to produce encrypted matrices that are appropriately averaged. \

Once these encrypted average matrices are produced, the cloud can then use their private key to decrypt the average matrices. Allowing them to reattach the weights and biases to the original model, ideally resulting in a new model which is more accurate than the original.

In the baseline linear regression on the MNIST dataset example I was able to produce the resulting confusion matrix. \

Demonstrating that when trained on all available MNIST data points, 60,000 data points, a linear regression model is able to achieve a 91.75% accuracy. This model appears to have an even distribution of all 10 digits, and was able to be trained in 54.8 seconds.

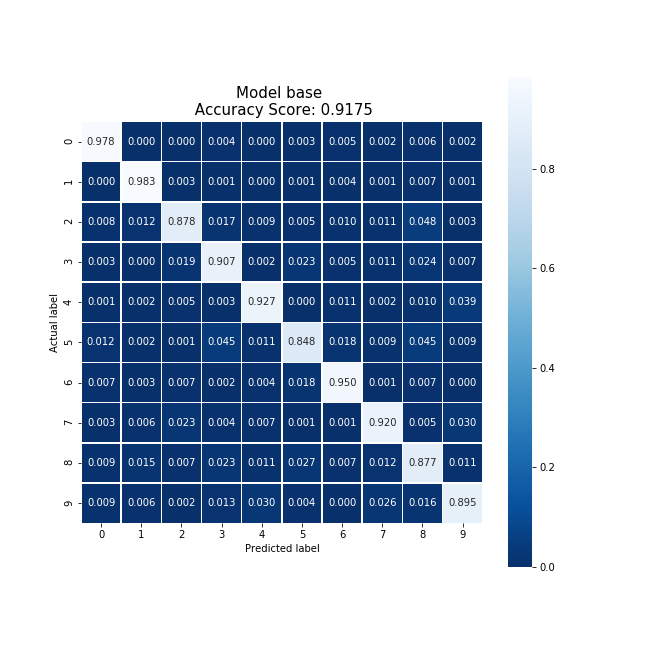

Once baseline was set, the cloud's confusion matrix could be produced. The cloud's model was trained on only 1,200 data points.

This confusion model shows the score of a a model that was trained on 1,200 data points in 1.06 seconds. This model produced an accuracy of 89.50% and also has an even distribution of most digits. The 2 and 9 digit case are predicted less frequently, resulting in a good test case for federated learning.

Once the cloud's model is trained all other parties' models can be trained in parallel.

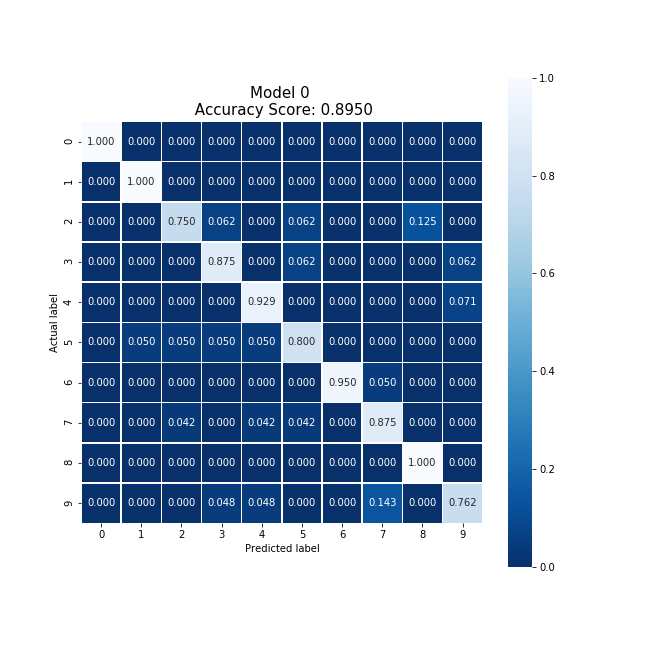

Party 1 was able to produce the following confusion matrix.

Producing a model with an accuracy of 93.62%, similar to the baseline example, after training on 30,000 local data points in 28.90 seconds. And producing the same even distribution as the baseline.

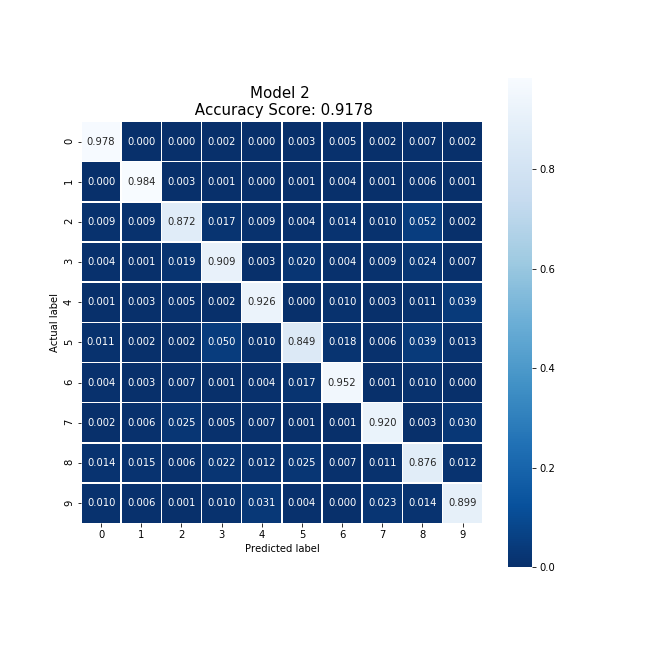

Party 2 was able to produce the following confusion matrix.

Producing a model with an accuracy of 91.78%, very similar to the baseline example, after training on only 3,000 local data points in 54.20 seconds. This model also was able to produce an even distribution, showing us that the 3,000 local data points were most likely evenly distributed between all 10 digits. Resulting in very little bias between digits.

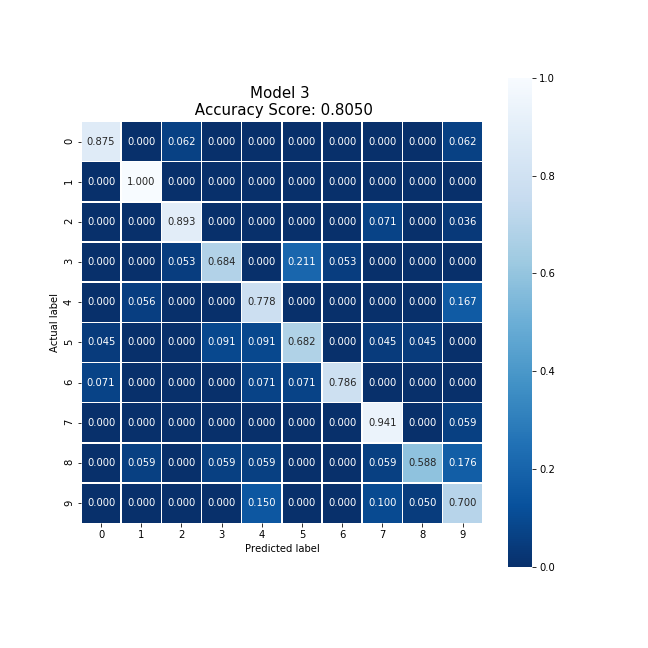

Party 3 was able to produce the following confusion matrix.

Producing a model with an accuracy of 80.50% after training for 1.08 seconds and producing strong biases towards 0, 1, 2, and 7. This model was trained on only 1,200 local data points, which is slightly surprising since this is a similar count to the cloud case.

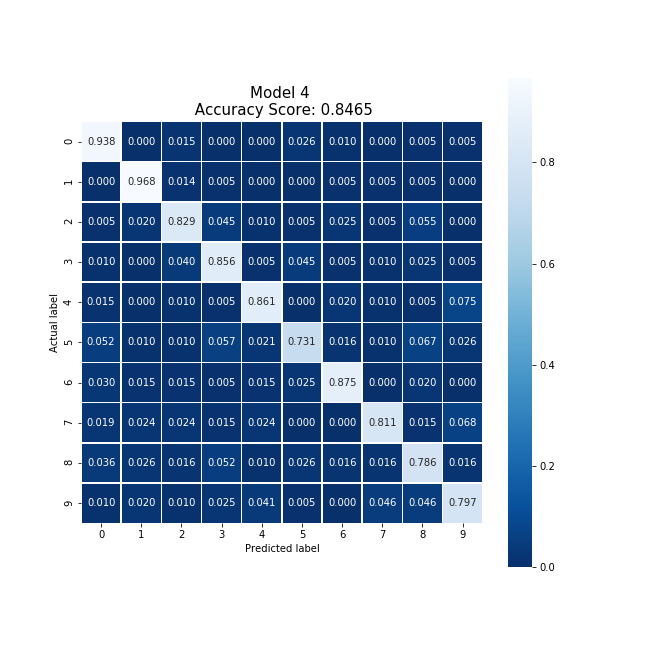

Party 4 was able to produce the following confusion matrix.

Producing a model with an accuracy of 84.65% after training for 9.63 seconds and producing no strong bias. This model was trained on 12,000 local data points.

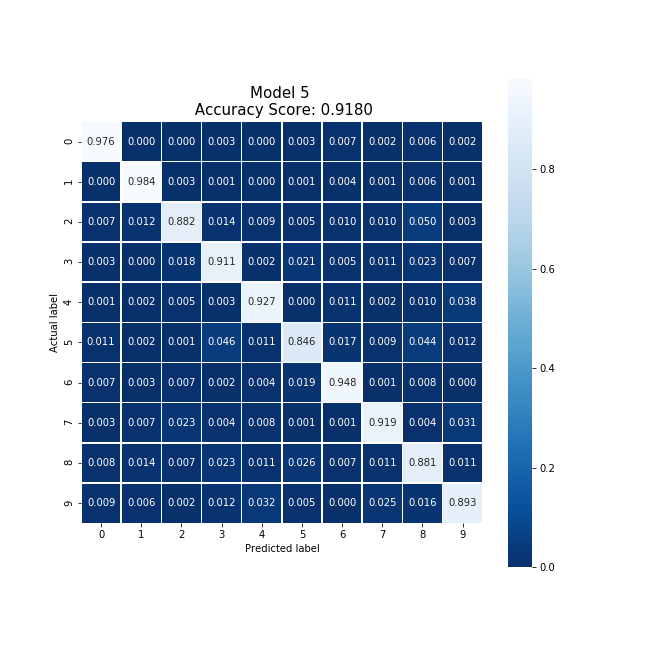

Party 5 was able to produce the following confusion matrix.

Producing a model with an accuracy of 91.80% after training on only 300 local data points in 53.3 seconds. The resulting confusion matrix also shows no strong biases toward any set of digits.

Once all models were trained in parallel they could then be averaged for the 2-party case.

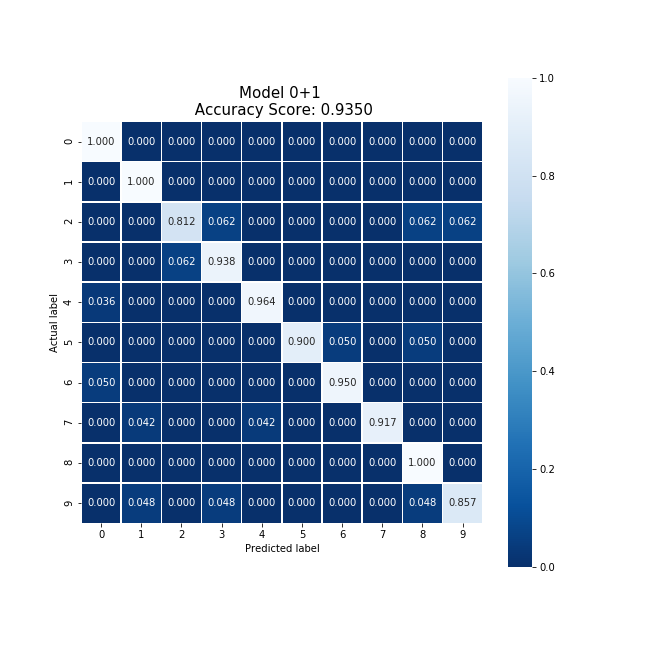

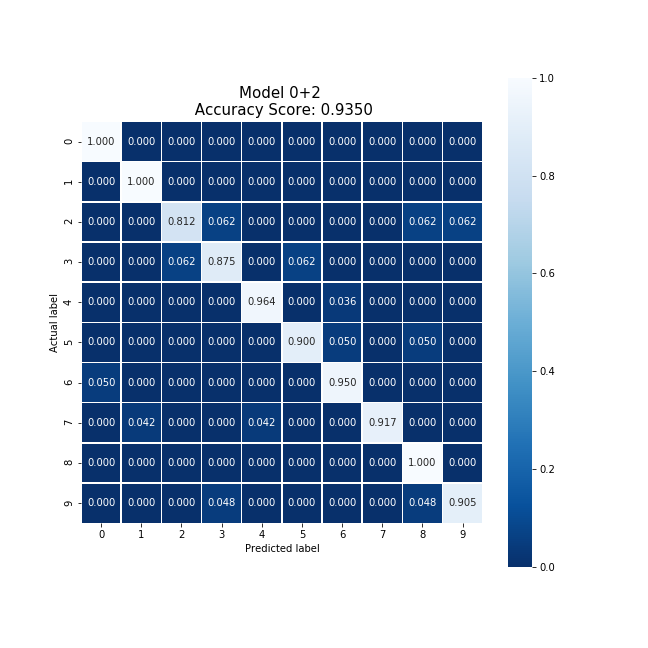

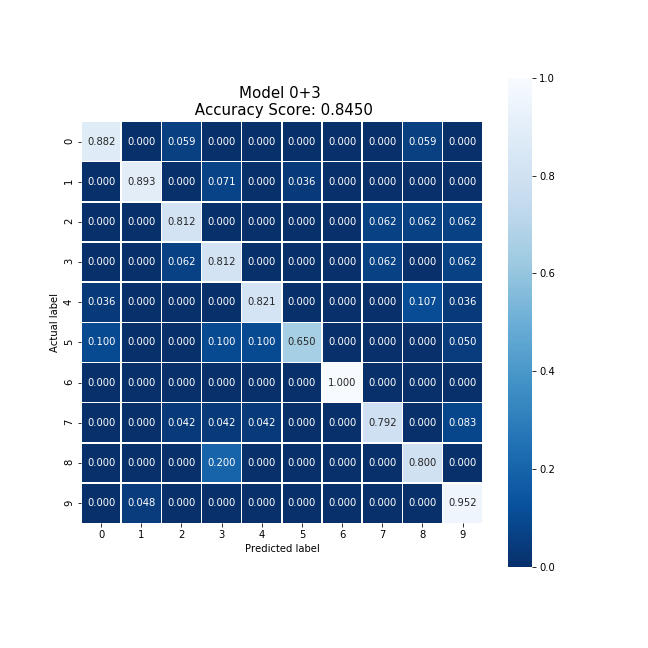

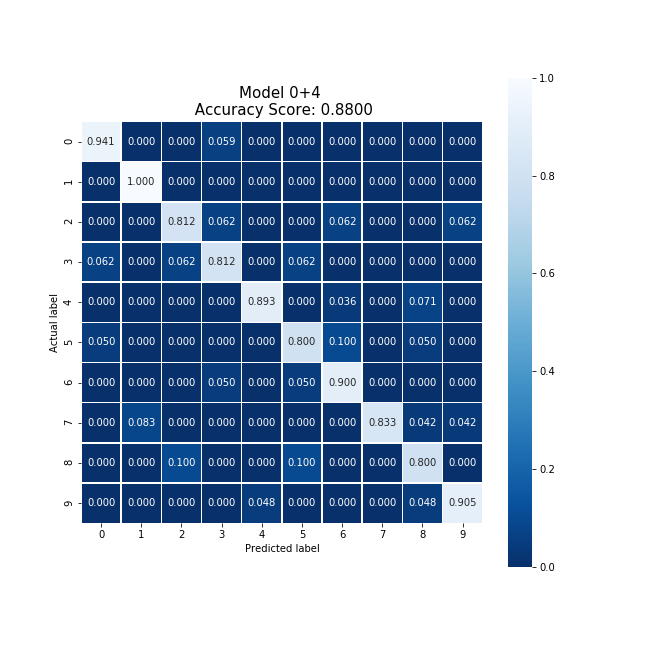

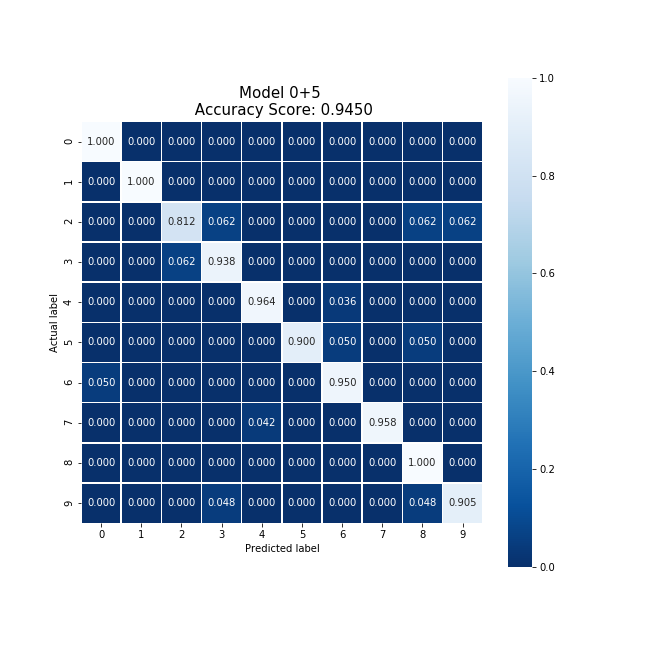

This produced the following confusion matrices.

Averaging the cloud model and party 1's model, we were able to produce a new model which collectively took 30.95 seconds to train, encrypt, and decrypt. This model produced an accuracy 4% higher than the original cloud model, and eliminated the original model's bias.

Averaging the cloud model and party 2's model, we were able to produce a new model which collectively took 56.29 seconds to train, encrypt, and decrypt. This model produced an accuracy 4% higher than the original cloud model, and slightly reduced the original model's bias.

Averaging the cloud model and party 3's model, we were able to produce a new model which collectively took 3.22 seconds to train, encrypt, and decrypt. This model produced an accuracy 5% lower than the original cloud model, and slightly reduced the original model's bias except for the 5 digit case.

Averaging the cloud model and party 4's model, we were able to produce a new model which collectively took 11.66 seconds to train, encrypt, and decrypt. This model produced an accuracy 1.5% lower than the original cloud model, and slightly reduced the original model's bias.

Averaging the cloud model and party 5's model, we were able to produce a new model which collectively took 55.40 seconds to train, encrypt, and decrypt. This model produced an accuracy 5% higher than the original cloud model, and reducing the original model's bias.

This last case is very interesting as the original model was trained on 1,200 data points and party 5's model was trained on 300 data points, resulting in two models which should not average to a new model with a high accuracy. However, this is not the case. This pair of models were able to produce a new model that outperforms all other models. According to McMahan's group [McMahan:Federated] this situation is not unheard of. In the event that two models are under-trained or over-fitted averaging two models can produce a new model which does not exibit the same degree of under-trained or over-fitted and will produce a model with a better accuracy than either case.

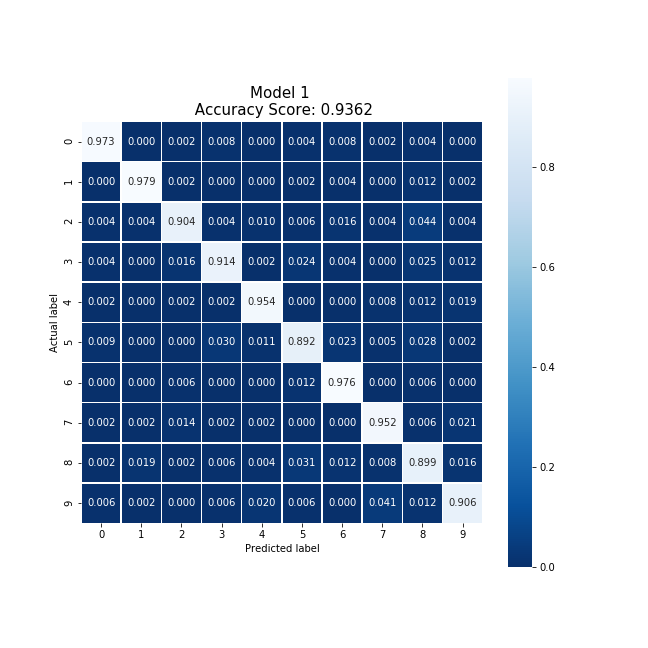

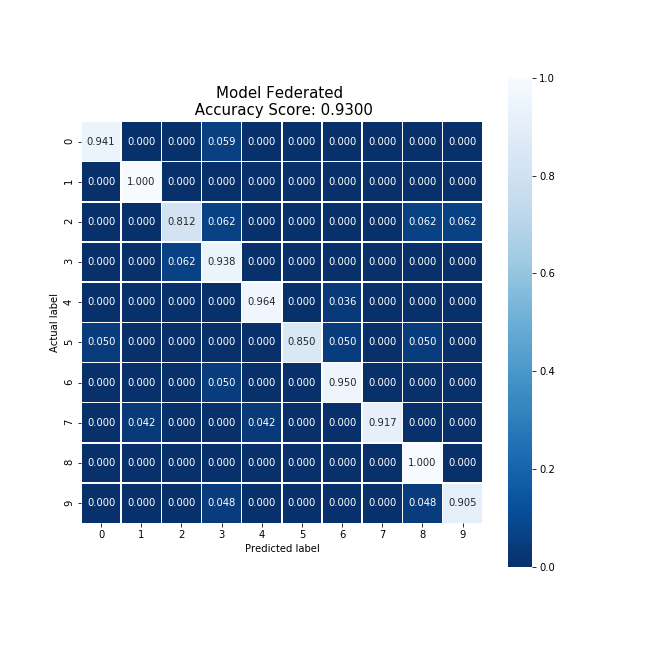

The last case explored was the 6-party case, generalized to an n-party case. This was able to produce the following model and confusion matrix.

This model was produced using all 6 trained models and was able to generate an accuracy score of 93.0%, 3.5% higher than the original model. This approach also performed 1.25% higher than the baseline model.

The federated model also does not appear to have a strong bias towards any digits in particular, which is desirable.

The two main concerns of federated learning was that it may not be accurate and may not be efficient. The first case has been proven false, with a higher accuracy in the n-party's model than the cloud's model. However, the second case still presents an issue at first glance. One might assume that the n-party's model took 149.97 seconds to train; however, federated learning is able to run in parallel. Meaning that rather than adding all training times for each party together we only need to take the max training time for any set of parties.

This produces a total training time of 56.45 seconds, which is only 0.16 seconds longer than the longest 2-party case and 1.64 seconds longer than the baseline example.

Federated learning is not immune to privacy threats. In the most trivial case if someone gets into your local device, your data is at risk. This is the trivial case as every privacy preserving mechanism is going to be vulnerable to this type of attack.

However, excluding the trivial case the aggregation phase of federated learning is vulnerable. In this phase all users send their ephemeral training summaries to the cloud, so that the cloud can average them or choose the most accurate for redistribution.

In this phase the cloud has access to the encrypted data and holds the private key necessary for decryption. This is a security risk as an adversarial cloud would be able to decrypt the averaged weights and biases and determine each user's original weights and biases.

Once in possession of these weights and biases the cloud could then reverse engineer the images required to generate those weights. This is very computationally expensive; however, is possible.

This can be overcome by performing differential privacy or secret sharing between parties so that the cloud does not have access to the encrypted data provided by the users. This methods has been shown to be effective, yet inefficient in many different studies. Such as in Geyer [Geyer:Differentially] and Nabi [Nabi:Privacy].

In the event that the cloud is trusted, this sort of attack can be made by one of the parties. If a party knows what the model was prior to distribution, observes the models sent during the aggregation phase, and knows what the updated model's weights and biases look like then they can infer which model was selected to yield those results. This type of attack requires the attacker to know a lot of encrypted details. However, is not impossible.

These attacks can be subverted by the same mechanisms established in the previous solution, but can also be solved by following Google's aggregation protocol [Research:Federated, Kone:Federated, Rodriguez:What]. Which states that summaries are uploaded in very specific cases where there is at a minimum hundreds or thousands of models which have been trained. This prevents all models except one from being blocked by an adversary forcing the system to select a specific user. This makes the likelihood of a breach computationally improbable.

[1] Federated learning: Collaborative machine learning without centralized training data, Apr 2017.

[2] R. A. N. J. K. S. M. S. H. M. B. . S. T. Andre Esteva, Brett Kuprel. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature, 2017.

[3] R. C. Geyer, T. Klein, and M. Nabi. Differentially Private Federated Learning: A Client Level Perspective. ArXiv e-prints, Dec. 2017.

[4] J. Konecny ́, H. B. McMahan, F. X. Yu, P. Richta ́rik, A. T. Suresh, and D. Bacon. Federated learning: Strategies for improving communication efficiency. CoRR, abs/1610.05492, 2016.

[5] H. B. McMahan, E. Moore, D. Ramage, and B. A. y Arcas. Federated learning of deep networks using model averaging. CoRR, abs/1602.05629, 2016.

[6] M. Nabi. Privacy-preserving collaborative machine learning - sap leonardo machine learning research - medium, Sep 2017.

[7] J. Rodriguez. What’s new in deep learning research: Understanding federated learning, Feb 2018.