HTTP is a protocol for fetching resources such as HTML documents. It is the foundation of any data exchange on the Web and it is a client-server protocol, which means requests are initiated by the recipient, usually the Web browser. A complete document is reconstructed from the different sub-documents fetched, for instance, text, layout description, images, videos, scripts, and more.

Following lists specify Application protocol for distributed hypermedia

- First documented in 1991 (HTTP/0.9)

- HTTP/1.0 introduced in 1996 (RFC 1945)

- HTTP/1.1 updated in 1999 (RFC 2616)

- HTTP/2.0 updated in 2015 (RFC 7540)

Hyper Text Transfer (HTTP) Protocol Request/Response includes Client and server exchange request/response messages, which uses the TCP protocol. For Client and server exchange request/response, the typical port number is 80.

Request structure

Response structure

Example:

An HTTP status code is a server response to a browser’s request. When you visit a website, your browser sends a request to the site’s server, and the server then responds to the browser’s request with a three-digit code: the HTTP status code.

1×× Informational

- 100 Continue

- 101 Switching Protocols

- 102 Processing

2×× Success

- 200 OK

- 201 Created

- 202 Accepted

- 204 No Content

- 206 Partial Content

3×× Redirection

- 300 Multiple Choices

- 301 Moved Permanently

- 302 Found

- 305 Use Proxy

4×× Client Error

- 400 Bad Request

- 401 Unauthorized

- 403 Forbidden

- 404 Not Found

- 405 Method Not Allowed

5×× Server Error

- 500 Internal Server Error

- 503 Service Unavailable

- 504 Gateway Timeout

- GET - retrieves whatever information identified by the Request-URL

- POST - sends data to the server for updates.

- PUT - requests that the enclosed entity stored under the supplied Request-URL.

- DELETE - requests the origin server to delete the resource identified by the Request-URL.

- HEAD - Similar to the GET method, except that the server must not return a message-body in the response.

- TRACE - Allows the client to see what received at the other end of the request chain and use that data for testing

HTTP headers let the client and the server pass additional information with an HTTP request or response. An HTTP header consists of its case-insensitive name followed by a colon (:), then by its value. Whitespace before the value is ignored.

- Accept: specify desired media type of response

- Accept-Language: specify the desired language of response

- Accept-Encoding: The encoding algorithm, usually a [compression algorithm]

- Date: date/time at which the message originated

- Host: host and port number of requested resource

- Referrer: URL of the previously visited resource

- User-Agent: identifier string for a Web browser or user agent

- Content-Language: the language of representation

- Content-Type: media type of representation

- Content-Length: length in bytes of representation

- Date: date/time at which the message originated

- Expires: date/time after which response is considered stale

- Last-Modified: date/time at which representation was last change

- Set-Cookie: used to send a cookie from the server to the user agent

Before HTTP/1.1, each HTTP request used a separate TCP connection as shown in the figure below.

HTTP/1.1 introduced the keyword “Keep-Alive.” TCP connections reused for multiple HTTP requests. HTTP uses the keyword “Keep-Alive” in the “Connection” header to denote that the connection is open for additional messages. “Keep-Alive” exists default in HTTP/1.1 while in HTTP/1.0, the default is to use a new connection for each request or reply pair.

HTTP/1.1 pipelining is a technique in which multiple HTTP requests sent on a single TCP connection without waiting for the corresponding responses.

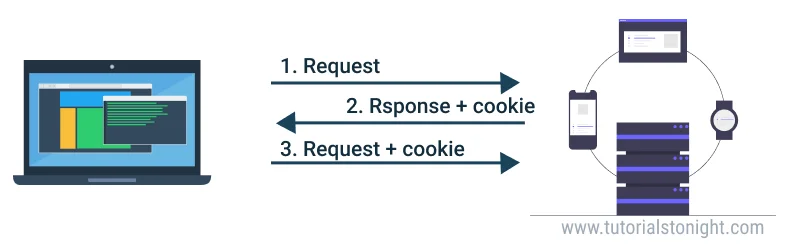

A cookie is a text file stored on the hard drive (more precisely in the browser folder) when visiting a website.

-

Session: They expire when the browser is closed or remained idle. For example, they are used in e�commerce websites to continue browsing without losing chosen items in the cart.

-

Permanent: They persist even after the browser exits. They have an expiration date though, as per law that limits lasting more than six months. They assist in remembering passwords and login information to reduce the need of re-entering them every time.

-

Third party: Third-party cookies are cookies that are set by a website other than the one you are currently on. For example, you can have a "Like" button on your website which will store a cookie on a visitor's computer, that cookie can later be accessed by Facebook to identify visitors and see which websites they visited. Such a cookie is considered to be a 3rd party cookie.

The Set-Cookie HTTP response header sends cookies from the server to the user agent. This header from the server tells the client to store a cookie.

This header from the server tells the client to store a cookie.

Now, with every new request to the server, the browser will send back all previously stored cookies to the server using the Cookie header.

HTTP supports the use of several authentication mechanisms to control access to pages and other resources. These mechanisms are all based around the use of the 401-status code and the WWW-�Authenticate response header.

The most widely used HTTP authentication mechanisms are as follows:

- Basic: The client sends the user name and password as encrypted base64 encoded text. It should only be used with HTTPS, as the password can be easily captured and reused over HTTP.

- Digest: The client sends a hashed form of the password to the server. Though the password cannot catch over HTTP, it may be possible to replay requests using the hashed password.

Force Authentication If an HTTP receives an anonymous request for a protected resource it can force the use of Basic authentication by rejecting the request with a 401 (Access Denied) status code and setting the WWW-�Authenticate response header as shown below:

The word Basic in the WWW-Authenticate selects the authentication mechanism that the HTTP client must use to access the resource. The realm string can be set to any value to identify the secure area and may be used by HTTP clients to manage passwords.

Most web browsers will display a login dialog when this response is received, allowing the user to enter a Username and Password. This information is then used to retry the request with an Authorization request header:

In computing, a user agent is a software (a software agent) that is acting on behalf of a user. One common use of the term refers to a web browser telling website information about the browser and operating system. This allows the website to customize content for the capabilities of a particular device, but also raises privacy issues. In HTTP, the User-Agent string often used for content negotiation, where the origin server selects suitable content or operating parameters for the response

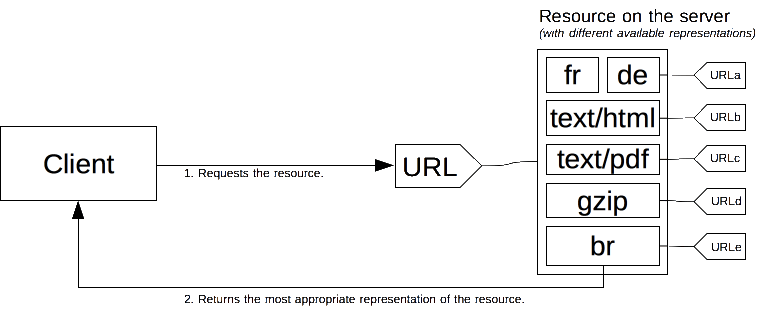

In HTTP, content negotiation is the mechanism that is used for serving different representations of a resource to the same URI to help the user agent specify which representation is best suited for the user (for example, which document language, which image format, or which content encoding).

A specific document is called a resource. When a client wants to obtain a resource, the client requests it via a URL. The server uses this URL to choose one of the variants available–each variant is called a representation–and returns a specific representation to the client. The overall resource, as well as each of the representations, has a specific URL. Content negotiation determines how a specific representation is chosen when the resource is called. There are several ways of negotiating between the client and the server.

HTTP provides for several different content negotiation mechanisms including:

- Server-driven

- Agent-driven

In server-driven content negotiation, or proactive content negotiation, the browser (or any other kind of user agent) sends several HTTP headers along with the URL. These headers describe the user's preferred choice. The server uses them as hints and an internal algorithm chooses the best content to serve to the client.

Example Negotiation Headers

- Accept: Which media types are acceptable for the response, such as “application/json,” “application/xml”.

- Accept-Charset: Which character sets are acceptable, such as UTF-8 or ISO 8859-1.

- Accept-Encoding: Which content encodings are acceptable, such as gzip.

- Accept-Language: The preferred natural language, such as "en-us."

HTTP allows another negotiation type: agent-driven negotiation or reactive negotiation. In this case, the server sends back a page that contains links to the available alternative resources when faced with an ambiguous request. The user is presented the resources and chooses the one to use.

HTTP is largely a text-based protocol. Binary content needs some way of transmission. MIME is an acronym for Multipurpose Internet Mail Extension. It is used to describe message content types. MIME messages can contain the text, images, audio, video and other application-specific data (For examples: PDF files, Microsoft Word Documents, and so on). It assists to make internet messages richer. It allows applications (and users) to exchange rich content other than text.

MIME types are defined using a <type>/<subtype> [optional parameters] format. Some typical examples are as follows:

| MIME Type | Extension(s) |

|---|---|

| application/json | json |

| application/pdf | |

| text/plain | txt |

| text/html | html ; htm |

| text/css | css |

| text/javascript | javascript |

| video/mp4 | mp4 |

| video/3gp | 3gp |

MIME passes as a part of the content type of the message header.

- Content-type: text/plain; charset=“us- ascii”

- The following example is a typical HTTP Response header (MIME highlighted)

When sending large messages, the message client splits them into smaller parts. This type of message is called a multi-part message. Multi-part messages have one of the MIME content types such as **content-�type = form-data

Web pages often contain content that remains unchanged for long periods. For example, an image containing a company logo may be used without modification for many years. It is wasteful in terms of bandwidth and round trips to repeatedly download images or other content that is not regularly updated.

HTTP supports caching so that content can be stored locally by the browser and reused when required. Of course, some types of data such as stock prices and weather forecasts are frequently changed and it is important that the browser does not display stale versions of these resources. By carefully controlling caching, it is possible to reuse static content and prevent the storage of dynamic data.

Browser caching is controlled by the use of the Cache-Control, Last-Modified and Expires response headers.

- Servers set the Cache-Control response header to no-cache to indicate that content should not be cached by the browser:

- Also, the Pragma header is also often used to stop caching by HTTP 1.0 proxies as they do not support the Cache-Control header:

The Cache-Control header can be set to one of the following values to allow caching:

- <absent>: If the Cache-Control header is not set, then any cache may store the content.

- Private: The content is intended for use by a single user and should only be cached locally in the browser.

- Public: The content may be cached in public caches (e.g. shared proxies) and private browser caches.

If the browser is to make effective use of cached content, two extra pieces of information should be supplied. The first is the modification date/time of the content. The server supplies this in the Last-Modified response header:

The second piece of information is the expiration date that is specified with the Expires header:

This header will set the cache expiration to be 31536000 seconds or one year in the future:

There are a number of situations in which Internet Explorer needs to check whether a cached entry is valid:

- The cached entry has no expiration date and the content is being accessed for the first time in a browser session

- The cached entry has an expiration date but it has expired

- The user has requested a page update by clicking the Refresh button or pressing F5

- If the cached entry has the last modification date, IE sends it in the If-Modified-Since header of a GET request message:

- The server checks the If-Modified-Since header and responds accordingly. If the content has not been changed since the date/time specified, it replies with a status code of 304 and a response message that just contains headers:

HTTP/2 is the first upgrade to the Hypertext Transfer Protocol since 1999. It’s goal is to improve website performance by optimizing how HTTP is expressed “on-the-wire.” It doesn’t change the semantics of HTTP, which means header fields, status codes, and cookies work exactly the same way as in HTTP/1.1.

HTTP/2 introduces several new features, and they’re all designed to improve page load times for your website visitors.

Multiplexing is perhaps the most significant benefit of HTTP/2. HTTP/1.1 requires each request to use its own TCP connection. Multiplexing, in contrast, allows a browser to include multiple requests in a single TCP connection.

The problem is, a browser can only have a limited number of TCP connections open at any given time. For HTTP/1.1, this means a browser can only load a single resource at a time—every asset in a web page is sent back to the browser sequentially. Multiplexing allows a browser to request all these assets in parallel. This results in a dramatic performance gain.

Modern websites rely on a lot of external assets: images, CSS, JavaScript, and fonts, just to name a few. Each time a browser requests one of these assets, it includes an HTTP header with the request. When the server sends the asset back to the browser, it also includes an HTTP response header. That’s a lot of overhead for the typical web page.

HTTP/2 forces all HTTP headers to be sent in a compressed format, reducing the amount of information that needs to be exchanged between browser and server. HTTP/1.1 does not provide any form of header compression.

HTTP/2 Server Push lets our edge network send web assets back to your browser before it even knows it needs them. This speeds up page load times by eliminating unnecessary round trips. For example, when a browser requests an HTML page, you can “push” all of the CSS stylesheets, image resources, and other assets inside of that web page. After the browser parses the HTML and finds all those assets, they’ll already be loaded into the local browser cache. This avoids extra requests back to the server.

Stream priority is a mechanism for browsers to specify which assets they would like to receive first. For example, an HTTP/2-aware browser can use stream priority to load the HTML for a page first, followed by CSS, then JavaScript, and finally image assets. This order allows the browser to render the page as quickly as possible.

You can think of stream priority as an optimization on top of multiplexing. Multiplexing lets you send several requests in a single TCP connection, and stream priority lets you define the order of the responses. While multiplexing eliminates much of the TCP overhead, it does nothing to optimize transfer times from the server to the browser. This is what stream priority is for.

REST stands for Representational State Transfer. (It is sometimes spelled “ReST.”) It relies on a stateless, client-server, cacheable communications protocol, and in virtually all cases, the HTTP protocol is used. REST is an architecture style for designing networked applications. The idea is that, rather than using complex mechanisms such as CORBA, RPC or SOAP to connect between machines, simple HTTP is used to make calls between machines. In many ways, the World Wide Web itself, based on HTTP, viewed as a REST-based architecture. RESTful applications use HTTP requests to post data (create and/or update), read data (e.g., make queries), and delete data. Thus, REST uses HTTP for all four CRUD (Create/Read/Update/Delete) operations.

WebSocket is a computer communications protocol, providing full-duplex communication channels over a single TCP connection. The WebSocket protocol was standardized by the IETF as RFC 6455 in 2011, and the WebSocket API in Web IDL is being standardized by the W3C. WebSocket is a different TCP protocol from HTTP.

To establish a WebSocket connection, the client sends a WebSocket handshake request, for which the server returns a WebSocket handshake response, as shown in the example below. Client request (just like in HTTP, each line ends with \r\n and there must be an extra blank line at the end)

Server response

Web app developers can implement a technique called HTTP long polling, where the client polls the server requesting new information. The server holds the request open until new data is available. Once available, the server responds and sends the new information. When the client receives the new information, it immediately sends another request, and the operation is repeated. This effectively emulates a server push feature.

WebDAV stands for Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning, which is an extension to HTTP that lets clients edit remote content on the web. In essence, WebDAV enables a web server to act as a file server, allowing authors to collaborate on web content.

WebDAV enriches the standard set of HTTP headers and methods to let you create, move and edit files, as well as delete or copy files and folders. As an extension to HTTP, Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning usually uses port 80 for plain, unencrypted access and port 443 if you use the SSL/TLS protocol.