- React is declarative. In a declarative program, the syntax itself describes what should happen, and the details of how things happen are abstracted away.

- React can be rendered isomorphically, which means that it can be in platforms other than the browser. This means we can render our UI on the server before it ever gets to the browser.

- Denormalized - means the same representation exists in multiple places

A higher-order component (HOC) is an advanced technique in React for reusing component logic. HOCs are not part of the React API, per se. They are a pattern that emerges from React’s compositional nature. Concretely, a higher-order component is a function that takes a component and returns a new component.

Whereas a component transforms props into UI, a higher-order component transforms a component into another component. HOCs are common in third-party React libraries, such as Redux’s connect.

- Redux itself just deals with JavaScript objects, so it provides the store, deals with actions and action creators, and handles reducers.

- React Redux provides connectors in order to connect Redux to our React components.

- Redux Thunk is a middleware that allows us to deal with asynchronous requests in Redux.

- Define the state

- Define the actions that are going to change the state

- Define the reducer functions which carry out the state modification

- Synchronous action creators: These simply return an action object

- Asynchronous action creators: These return an async function, which will later dispatch an action

Redux reducers differ from Reducer Hooks in that they have certain conventions:

- Each reducer needs to set its initial state by defining a default value in the function definition

- Each reducer needs to return the current state for unhandled actions

Container components use a connector to connect Redux to a presentational component. This connector accepts two functions:

- mapStateToProps(state): Takes the current Redux state, and returns an object of props to be passed to the component; used to pass state to the component

- mapDispatchToProps(dispatch): Takes the dispatch function from the Redux store, and returns an object of props to be passed to the component; used to pass action creators to the component

The useDispatch Hook returns a reference to the dispatch function that is provided by the Redux store. It can be used to dispatch actions that are returned from action creators.

import React from 'react'

import { useDispatch } from 'react-redux'

export const CounterComponent = ({ value }) => {

const dispatch = useDispatch()

return (

<div>

<span>{value}</span>

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: 'increment-counter' })}>

Increment counter

</button>

</div>

)

}

Reminder: when passing a callback using dispatch to a child component, you should memoize it with useCallback, just like you should memoize any passed callback. This avoids unnecessary rendering of child components due to the changed callback reference. You can safely pass [dispatch] in the dependency array for the useCallback call - since dispatch won't change, the callback will be reused properly (as it should).

import React, { useCallback } from 'react'

import { useDispatch } from 'react-redux'

export const CounterComponent = ({ value }) => {

const dispatch = useDispatch()

const incrementCounter = useCallback(

() => dispatch({ type: 'increment-counter' }),

[dispatch]

)

return (

<div>

<span>{value}</span>

<MyIncrementButton onIncrement={incrementCounter} />

</div>

)

}

export const MyIncrementButton = React.memo(({ onIncrement }) => (

<button onClick={onIncrement}>Increment counter</button>

))

const result = useSelector(selectorFn, equalityFn)

selectorFn is a function that works similarly to the mapStateToProps function. It will get the full state object as its only argument. The selector function gets executed whenever the component renders, and whenever an action is dispatched (and the state is different than the previous state).

Basic usage:

import React from 'react'

import { useSelector } from 'react-redux'

export const CounterComponent = () => {

const counter = useSelector(state => state.counter)

return <div>{counter}</div>

}

Using props via closure to determine what to extract:

import React from 'react'

import { useSelector } from 'react-redux'

export const TodoListItem = props => {

const todo = useSelector(state => state.todos[props.id])

return <div>{todo.text}</div>

}

The useEffect Hook accepts a function that contains code with side effects. The function passed to the Hook will run after the render is done and the component is on the screen.

A cleanup function can be returned from the Hook, which will be called when the component unmounts and is used to, for example, clean up timers or subscriptions. The cleanup function will also be called before the effect is triggered again, when dependencies of the effect update. Also note that useEffect callbacks are only called if they have no dependencies listed or if they have a dependency listed and one of those dependencies changed.

To avoid triggering the effect on every re-render, we can specify an array of values as the second argument to the Hook. Only when any of these values change, the effect will get triggered again.

This array passed as the second argument is called the dependency array of the effect. If you want the effect to only trigger during mounting, and the cleanup function during unmounting, we can pass an empty array as the second argument. The dependency array can be used to control when an effect is invoked.

The render always comes before useEffect. The render happens first and then all effects run in order with full access to all of the values from the render.

We use useEffect when a render needs to cause side effects. Think of a side effect as something that a function does that isn’t part of the return. But we might want the component to do more than that. Those things we want the component to do other than return UI are called effects.

Every time we render, useEffect has access to the latest values from that render: props, state, refs, etc. Think of useEffect as being a function that happens after a render. When a render fires, we can take a look at that render’s values and use them in the effect. Then once we render again, the whole thing starts over. New values, then new renders, then new effects.

Effects that are only invoked on the first render are extremely useful for initialization. If you return a function from the effect, the function will be invoked when the component is removed from the tree.

Giving it an empty array acts like componentDidMount as in, it only runs once. An empty dependency array causes the effect to only be invoked once after the initial render.

Giving it no second argument acts as both componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate, as in it runs first on mount and then on every re-render.

Giving it an array as second argument with any value inside will only execute the code inside your useEffect hook ONCE on mount, as well as whenever that particular variable changes.

The memo function can be used to create a component that will only render when its properties change. The second argument sent to the memo function is a predicate. A predicate is a function that only returns true or false. The predicate receives the previous properties and the next properties. React.memo is only for function components.The useMemo Hook takes a result of a function and memoizes it. This means that it will not be recomputed every time. This Hook can be used for performance optimizations. In a memoized function, the result of a function call is saved and cached. Then when the function is called again with the same inputs, the cached value is returned.

useMemo runs during rendering, so make sure the computation function does not cause any side effects, such as resource requests. Side effects should be put into a useEffect Hook.

The array passed as the second argument specifies the dependencies of the function. If any of these values change, the function will be recomputed; otherwise, the stored result will be used. If no array is provided, a new value will be computed on every render. If an empty array is passed, the value will only be computed once.

useMemo is similar to useCallback except it allows you to apply memoization to any value type (not just functions). It does this by accepting a function which returns the value and then that function is only called when the value needs to be retrieved (which typically will only happen once each time an element in the dependencies array changes between renders).

The useCallback Hook works similarly to the useMemo Hook. However, it returns a memoized callback function instead of a value. The function returned will only be redefined if one of the dependency values passed in the array of the second argument changes.const memoizedCallback = useCallback(

() => doSomething(a, b, c),

[a, b, c]

)

The previous code is similar to the following useMemo Hook:

const memoizedCallback = useMemo(

() => () => doSomething(a, b, c),

[a, b, c]

)

function CandyDispenser() {

const initialCandies = ['snickers', 'skittles', 'twix', 'milky way']

const [candies, setCandies] = React.useState(initialCandies)

// ----- Original code -----

const dispense = candy => {

setCandies(allCandies => allCandies.filter(c => c !== candy))

}

// ----- Original code -----

// ----- useCallback -----

const dispense = React.useCallback(candy => {

setCandies(allCandies => allCandies.filter(c => c !== candy))

}, [])

// ----- useCallback -----

// ----- useCallback refactored -----

const dispense = candy => {

setCandies(allCandies => allCandies.filter(c => c !== candy))

}

const dispenseCallback = React.useCallback(dispense, [])

// ----- useCallback refactored -----

return (

<div>

<h1>Candy Dispenser</h1>

<div>

<div>Available Candy</div>

{candies.length === 0 ? (

<button onClick={() => setCandies(initialCandies)}>refill</button>

) : (

<ul>

{candies.map(candy => (

<li key={candy}>

<button onClick={() => dispense(candy)}>grab</button> {candy}

</li>

))}

</ul>

)}

</div>

</div>

)

}

Performance optimizations are not free. They ALWAYS come with a cost but do NOT always come with a benefit to offset that cost.

There are specific reasons both of these hooks are built-into React:

- Referential equality

- Computationally expensive calculations

https://kentcdodds.com/blog/usememo-and-usecallback

In React, a ref is an object that stores values for the lifetime of a component.The useRef Hook returns a ref object that can be assigned to a component or element via the ref prop.

After assigning the ref to an element or component, the ref can be accessed via refContainer.current. If InitialValue is set, refContainer.current will be set to this value before assignment.

When calling useRef(), you’re creating an object. This object is a container for storing any mutable value. Refs persist between renders but don’t trigger re-renders.

Updating a ref value is considered a side effect. This is the reason why you want to update your ref value in event handlers and effects and not during rendering (unless you are working on lazy initialization).

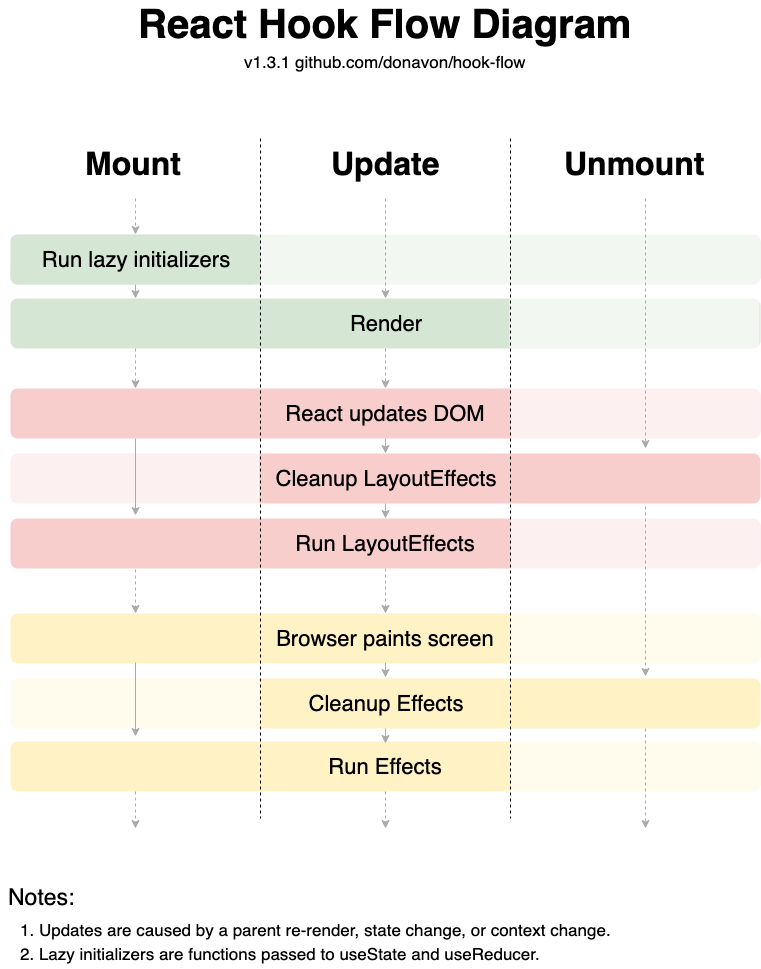

The useLayoutEffect Hook is identical to the useEffect Hook, but it fires synchronously after all DOM mutations are completed and before the component is painted on the browser.

Do not use this Hook unless it is really needed, which is only in certain edge cases. useLayoutEffect will block visual updates in the browser, and thus, is slower than useEffect.

The rule here is to use useEffect first. If your mutation changes the appearance of the DOM node, which can cause it to flicker, you should use useLayoutEffect instead.

- render

- useLayoutEffect is called

- Browser Paint: the time when the component’s elements are actually added to the DOM

- useEffect is called

useLayoutEffect is invoked after the render, but before the browser paints the change. In most circumstances, useEffect is the right tool for the job, but if your effect is essential to the browser paint, you may want to use useLayoutEffect. For instance, you may want to obtain the with and height of an element when the window is resized. The width and height of the window is information that your component may need before the browser paints. useLayoutEffect is used to calculate the window’s width and height before the paint.

function useWindowSize {

const [width, setWidth] = useState(0);

const [height, setHeight] = useState(0);

const resize = () => {

setWidth(window.innerWidth);

setHeight(window.innerHeight);

};

useLayoutEffect(() => {

window.addEventListener("resize", resize);

resize();

return () => window.removeEventListener("resize", resize);

}, []);

return [width, height];

};

Another example of when to use useLayoutEffect is when tracking the position of the mouse.

function useMousePosition {

const [x, setX] = useState(0);

const [y, setY] = useState(0);

const setPosition = ({ x, y }) => {

setX(x);

setY(y);

};

useLayoutEffect(() => {

window.addEventListener("mousemove", setPosition);

return () => window.removeEventListener("mousemove", setPosition);

}, []);

return [x, y];

};

The useContext Hook accepts a context object and returns the current value for the context. When the context provider updates its value, the Hook will trigger a re-render with the latest value.

Using createContext we created a new instance of React context that we named ColorContext. The color context contains two components: the ColorContext.Provider and the ColorContext.Consumer. We need to use the provider to place the colors in state. We add data to context by setting the value property of the Provider.

The Provider will only provide context values to it’s children. The useContext hooks requires the context instance to obtain values from it. In other words the context object itself needs to be passed to the Hook, not the consumer or provider.

The Consumer is accessed within the useContext hook, which means that we no longer have to work directly with the consumer component.

The context provider can place an object into context, but it can’t mutate the values in context on its own. It needs some help from a parent component. The trick is to create a stateful component that renders a context provider. When the state of the stateful component changes, it will rerender the context provider with new context data. Any of the context providers’ children will also be rerendered with the new context data. The stateful component that renders the context provider is our custom provider. That is: that’s the component that will be used when it’s time to wrap our App with the provider.

An alternative to useState. Accepts a reducer of type (state, action) => newState, and returns the current state paired with a dispatch method. useReducer is usually preferable to useState when you have complex state logic that involves multiple sub-values or when the next state depends on the previous one. useReducer also lets you optimize performance for components that trigger deep updates because you can pass dispatch down instead of callbacks.const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialArg, init);

- useMemo is to memoize a calculation result between a function's calls and between renders

- useCallback is to memoize a callback itself (referential equality) between renders

- useRef is to keep data between renders (updating does not fire re-rendering)

- useState is to keep data between renders (updating will fire re-rendering)

useMemo focuses on avoiding heavy calculation.

useCallback focuses on a different thing: it fixes performance issues when inline event handlers like onClick={() => { doSomething(...); } cause PureComponent child re-rendering (because function expressions there are referentially different each time)

This said, useCallback is closer to useRef, rather than a way to memoize a calculation result.

React components provide instructions for React to follow when creating and managing updates to the DOM. We can test these components by rendering them and checking the resulting DOM.We are not running our tests in a browser; we are running them in the terminal with Node.js. Node.js does not have the DOM API that comes standard with each browser. Jest incorporates an npm package called jsdom that is used to simulate a browser environment in Node.js, which is essential for testing React components.

The documentation provides more detail about all of the custom matchers that are available to that you can test exactly what you want to test: https://github.com/testing-library/jest-dom#custom-matchers.

Testing Library is an umbrella over many testing packages for libraries like Vue, Svelte, Reason, Angular, and more. It’s not just for React.

If we want the component to render, a function that is part of React Testing Library, render, will help us do just that. render will replace our need to use ReactDOM.render(). render will take in one argument - the component or element that we want to render. The function returns an object of queries that can be used to check in with values in that component or element.

Code coverage is the process of reporting on how many lines of code have actually been tested. It provides a metric that can help you decide when you have written enough tests.

To run Jest with code coverage, simply add the coverage flag when you run the jest command:

- npm test -- --coverage

- npm test -- --coverage --watchAll=false *Generates coverage report

- ReactDOM.render: Renders html directly in the browser

- ReactDOM.renderToString: Renders html as a string, this allows us to render UI on the server.

A render prop can contain a component to render when a particular condition has been met.

The virtual DOM (VDOM) is a programming concept where an ideal, or “virtual”, representation of a UI is kept in memory and synced with the “real” DOM by a library such as ReactDOM. This process is called reconciliation.

DOM stands for Document Object Model and is an abstraction of a structured text. For web developers, this text is an HTML code, and the DOM is simply called HTML DOM. Elements of HTML become nodes in the DOM.

“virtual DOM” is more of a pattern than a specific technology.

In React, for every DOM object, there is a corresponding “virtual DOM object.” A virtual DOM object is a representation of a DOM object, like a lightweight copy. A virtual DOM object has the same properties as a real DOM object, but it lacks the real thing’s power to directly change what’s on the screen.

When you render a JSX element, every single virtual DOM object gets updated.This sounds incredibly inefficient, but the cost is insignificant because the virtual DOM can update so quickly.

Once the virtual DOM has updated, React compares the virtual DOM with a virtual DOM snapshot that was taken right before the update.

By comparing the new virtual DOM with a pre-update version, React figures out exactly which virtual DOM objects have changed. This process is called “diffing.”

Once React knows which virtual DOM objects have changed, then React updates those objects, and only those objects, on the real DOM.

This is the primary type in React.

A ReactElement is a light, stateless, immutable, virtual representation of a DOM Element.

ReactElements lives in the virtual DOM. They make the basic nodes here. Their immutability makes them easy and fast to compare and update. This is the reason of great React performance.

What can be a ReactElement? Almost every HTML tag - div, table, strong…

Once defined, ReactElements can be render into the “real” DOM. This is the moment when React ceases to control the elements. They become slow, boring DOM nodes.

ReactElements are the basic items in React-ish virtual DOM. However, they are stateless, therefore don’t seem to be very helpful for us, the programmers.

What differs ReactComponent from ReactElement is - ReactComponents are stateful.

ReactComponents turned out to be a great tool for designing dynamic HTML. They don’t have the access to the virtual DOM, but they can be easily converted to ReactElements.

Whenever a ReactComponent is changing the state, we want to make as little changes to the “real” DOM as possible. So this is how React deals with it. The ReactComponent is converted to the ReactElement. Now the ReactElement can be inserted to the virtual DOM, compared and updated fast and easily. How exactly - well, that’s the job of the diff algorithm. The point is - it’s done faster than it would be in the “regular” DOM.

When React knows the diff - it’s converted to the low-level (HTML DOM) code, which is executed in the DOM. This code is optimised per browser.

When we pass the array of elements to a component, we need to surround it with curly braces. This is called a JavaScript expression, and we must use these when passing JavaScript values to components as properties.Component properties will take two types: either a string or a JavaScript expression. JavaScript expressions can include arrays, objects, and even functions. In order to include them, you must surround them in curly braces.

JSX is JavaScript, so you can incorporate JSX directly inside of JavaScript functions.

JSX looks clean and readable, but it can’t be interpreted with a browser. All JSX must be converted into createElement calls or factories. Luckily, there is an excellent tool for this task: Babel.

JavaScript is an interpreted language: the browser interprets the code as text, so there is no need to compile JavaScript. However, not all browsers support the latest JavaScript syntax, and no browser supports JSX syntax. Since we want to use the latest features of JavaScript along with JSX, we are going to need a way to convert our fancy source code into something that the browser can interpret. This process is called compiling, and it is what Babel is designed to do.

React will not render two or more adjacent or sibling elements as a component, so we used to have to wrap these in an enclosing tag like a div. This led to a lot of unnecessary tags being created though, a bunch of wrappers without much purpose. If we use a React Fragment, we can mimic the behavior of a wrapper without actually creating a new tag. react-scripts was also created by Facebook and is where the real magic happens. It installs Babel, ESLint, webpack, and more, so that you don’t have to configure them manually. A Pure Component is a function component that does not contain state and will render the same user interface given the same props. In React, a Pure Component is a Component that always renders the same output, given the same properties.In a nutshell, rendering is the process of transforming your react components into DOM (Document Object Model) nodes that your browser can understand and display on the screen.

DOM manipulation is extremely slow. In contrast, manipulating React elements is much, much faster. React makes the most of this by creating a virtual representation of what the DOM should look like called the Virtual DOM[1].

Whenever you make any changes to your running React application, such as entering text, removing an element, adding an element, etc, React will batch all of these changes together in its Virtual DOM, then compare this representation with the actual DOM, find what needs to be updated, and then make the smallest possible changes to the real DOM to keep them in sync while keeping the application performant.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that React separates itself into 2 libraries: the main React library and the ReactDOM library. The React library handles all of the element creation and manipulation while the ReactDOM library is solely in charge of rendering those elements to the browser. This separation of concerns allows React to not only target the browser, but any other platform as well.

When a change occurs, React makes a copy of the component tree as a JavaScript object. It looks for the parts of the tree that need to change and changes only those parts. Once complete, the copy of the tree (known as the work-in-progress tree) replaces the existing tree. It’s important to reiterate that it uses the parts of the tree that are already there.Fiber, released in version 16.0, rewrote the way that DOM updates worked by taking a more asynchronous approach. The first change with 16.0 was the separation of the renderer and the reconciler. A renderer is the part of the library that handles rendering, and the reconciler is the part of the library that manages updates when they occur.

Separating the renderer from the reconciler was a big deal. The reconciliation algorithm was kept in React Core (the package you install to use React), and each rendering target was made responsible for rendering. In other words, ReactDOM, React Native, React 360, and more would be responsible for the logic of rendering and could be plugged into React’s core reconciliation algorithm.

Another huge shift with React Fiber was its changes to the reconciliation algorithm. Remember our expensive DOM updates that blocked the main thread? This lengthy block of updates is called work—with Fiber, React split the work into smaller units of work called fibers. A fiber is a JavaScript object that keeps track of what it’s reconciling and where it is in the updating cycle.

Once a fiber (unit of work) is complete, React checks in with the main thread to make sure there’s not anything important to do. If there is important work to do, React will give control to the main thread. When it’s done with that important work, React will continue its update. If there’s nothing critical to jump to on the main thread, React moves on to the next unit of work and renders those changes to the DOM.

Fiber provides the infrastructure for prioritizing updates. In the longer term, the developer may even be able to tweak the defaults and decide which types of tasks should be given the highest priority. The process of prioritizing units of work is called scheduling; this concept underlies the experimental concurrent mode, which will eventually allow these units of work to be performed in parallel.