Click ⭐if you like the project. Pull Requests are highly appreciated. Follow @iamtalvinder for more frontend insights.

-

These six types are considered to be primitives. A primitive is not an object and has no methods of its own. All primitives are immutable.

-

String: Collection of characters i.e words.

-

Number: integers, floats, etc.

-

Boolean true or false

-

Null it represents no value. However, the typeof(null) is an object in javascript/

-

Undefined a declared variable but hasn’t been given a value.

-

Symbol a unique value that's not equal to any other value.

-

-

The JavaScript ES6 introduced a new primitive data type called Symbol. Symbols are immutable (cannot be changed) and are unique. For example -

// two symbols with the same description const value1 = Symbol('hello'); const value2 = Symbol('hello'); console.log(value1 === value2); // false

Use the Symbol() function to create a Symbol. For example -

// creating symbol const z = Symbol() typeof z; // symbol

Type of a symbol is a symbol.

You can pass an optional string as its description.

const z = Symbol('hello'); console.log(z); // Symbol(hello) console.log(z.description); // hello

You can add symbols as a key in an object using square brackets []. For example -

let id = Symbol("id"); let person = { name: "John", // adding symbol as a key [id]: 123 // not "id": 123 }; console.log(person); // {name: "John", Symbol(id): 123}

Note: Symbols are not included in for...in Loop

If the same code is used multiple times, then it is better to use Symbols in the object key. It's because you can use the same key name in different codes and avoid duplication issues. For example -

let person = { name: "Jack" }; // creating Symbol let id = Symbol("id"); // adding symbol as a key person[id] = 23;

In the above program, if the person object is also used by another program, then you wouldn't want to add a property that can be accessed or changed by another program. Hence by using Symbol, you create a unique property that you can use.

-

In JavaScript, undefined means a variable has been declared but has not yet been assigned a value, such as:

var testVar; console.log(testVar); //shows undefined console.log(typeof testVar); //shows undefined

null is an assignment value. It can be assigned to a variable as a representation of no value:

var testVar = null; console.log(testVar); //shows null console.log(typeof testVar); //shows object

You may wonder why the typeof returns 'object' for a value that is null. This was actually an error in the original JavaScript implementation that was then copied in ECMAScript. Today, it is rationalized that null is considered a placeholder for an object, even though, technically, it is a primitive value."

-

The Set object lets you store unique values of any type, whether primitive values or object references.

const mySet1 = new Set() mySet1.add(1) // Set [ 1 ] mySet1.add(5) // Set [ 1, 5 ] mySet1.add(5) // Set [ 1, 5 ] mySet1.add('some text') // Set [ 1, 5, 'some text' ] const o = {a: 1, b: 2} mySet1.add(o) mySet1.add({a: 1, b: 2}) // o is referencing a different object, so this is okay mySet1.has(1) // true mySet1.has(3) // false, since 3 has not been added to the set mySet1.has(5) // true mySet1.has(Math.sqrt(25)) // true mySet1.has('Some Text'.toLowerCase()) // true mySet1.has(o) // true mySet1.size // 5 mySet1.delete(5) // removes 5 from the set mySet1.has(5) // false, 5 has been removed mySet1.size // 4, since we just removed one value console.log(mySet1) // logs Set(4) [ 1, "some text", {…}, {…} ] in Firefox // logs Set(4) { 1, "some text", {…}, {…} } in Chrome

-

Using the Set constructor and the spread syntax:

uniq = [...new Set(array)];

for example -

let arr = [1,2,1,1,4,6,3,5,2,6,5]; console.log([...new Set(arr)]); //console.log([...new Set(arr)])

-

Regular functions return only one, single value (or nothing).

Generators can return (“yield”) multiple values, one after another, on-demand. They work great with iterables, allowing to create data streams with ease. To create a generator, we need a special syntax construct: function*, so-called “generator function”.

function* generateSequence() { yield 1; yield 2; return 3; }

Generator functions behave differently from regular ones. When such function is called, it doesn’t run its code. Instead it returns a special object, called “generator object”, to manage the execution.

function* generateSequence() { yield 1; yield 2; return 3; } // "generator function" creates "generator object" let generator = generateSequence(); console.log(generator); // [object Generator] let one = generator.next(); console.log(JSON.stringify(one)); // {value: 1, done: false}

As of now, we got the first value only, and the function execution is on the second line:

let two = generator.next(); console.log(JSON.stringify(two)); // {value: 2, done: false}

And, if we call it a third time, the execution reaches the return statement that finishes the function:

let three = generator.next(); alert(JSON.stringify(three)); // {value: 3, done: true}

Now the generator is done. We should see it from done:true and process value:3 as the final result.

Note: Generators are iterable.

-

Arrow functions allow us to write shorter function syntax. The handling of this is also different in arrow functions compared to regular functions. In regular functions the this keyword represented the object that called the function, which could be the window, the document, a button or whatever. With arrow functions the this keyword always represents the object that defined the arrow function.

//before hello = function() { return "Hello World!"; } //after hello = () => { return "Hello World!"; }

-

A JavaScript class is a blueprint for creating objects. A class encapsulates data and functions that manipulate the data.

Unlike other programming languages such as Java and C++, JavaScript classes are syntactic sugar over the prototypal inheritance. In other words, ES6 classes are just special functions.

class Person { constructor(name) { this.name = name; } getName() { return this.name; } } let john = new Person("John Doe"); let name = john.getName(); console.log(name); // "John Doe"

-

In JavaScript, prototype refers to a system. This system allows you to define properties on objects that can be accessed via the object’s instances.

For example, an Array is a blueprint for array instances. You create an array instance with [] or new Array().

const array = ['one', 'two', 'three'] console.log(array); // Same result as above const array = new Array('one', 'two', 'three');

If you console.log this array you won’t see any methods, but you can use methods like concat, slice, filter, and map!

Why?

Because these methods are located in the Array’s prototype. You can expand the proto object (Chrome Devtools) or prototype object (Firefox Devtools) and you’ll see a list of methods.

When you use map, JavaScript looks for map in the object itself. If map is not found, JavaScript will try to look for a Prototype. If JavaScript finds a prototype, it continues to search for map in that prototype.

So the correct definition for Prototype is: An object that instances can access when they’re trying to look for a property.

Step 1: JavaScript checks if the property is available inside the object. If yes, JavaScript uses the property straight away.

Step 2: If the property is NOT inside the object, JavaScript checks if there’s a Prototype available. If there is a Prototype, repeat Step 1 (and check if the property is inside the prototype).

Step 3: If there are no more Prototypes left, and JavaScript cannot find the property, it does returns undefined or throws error depending upon if you called a property or method.

-

The this references the object of which the function is a property. In other words, the this references the object that is currently calling the function.

Suppose that you have an object called counter. This object counter has a method called next().

When you call the next() method, you can access the this object.

const counter = { count: 0, next: function () { return ++this.count; } }; counter.next();

The next() is a function which is the property of the counter object. Therefore, inside the next() function, the this references the counter object.

By the way, when a function is a property of an object, it is called a method.

-

In Javascript, events bubbles by default, so it becomes extremely important to understand the difference:

target = element that triggered event

currentTarget = element that listens to event.

For example - you can have a click event listener on ul but if you click on li when target event.target will be li and event.currentTarget will be the ul.

-

Back in the old days, Netscape advocated event capturing, while Microsoft promoted event bubbling.

Event bubbling and capturing are two ways of event propagation in the HTML DOM API, when an event occurs in an element inside another element, and both elements have registered a handle for that event. The event propagation mode determines in which order the elements receive the event.

With bubbling, the event is first captured and handled by the innermost element and then propagated to outer elements.

With capturing, the event is first captured by the outermost element and propagated to the inner elements.

We can use the below code -

addEventListener(type, listener, useCapture)

to register event handlers for in either bubbling (default) or capturing mode. To use the capturing model pass the third argument as true.

-

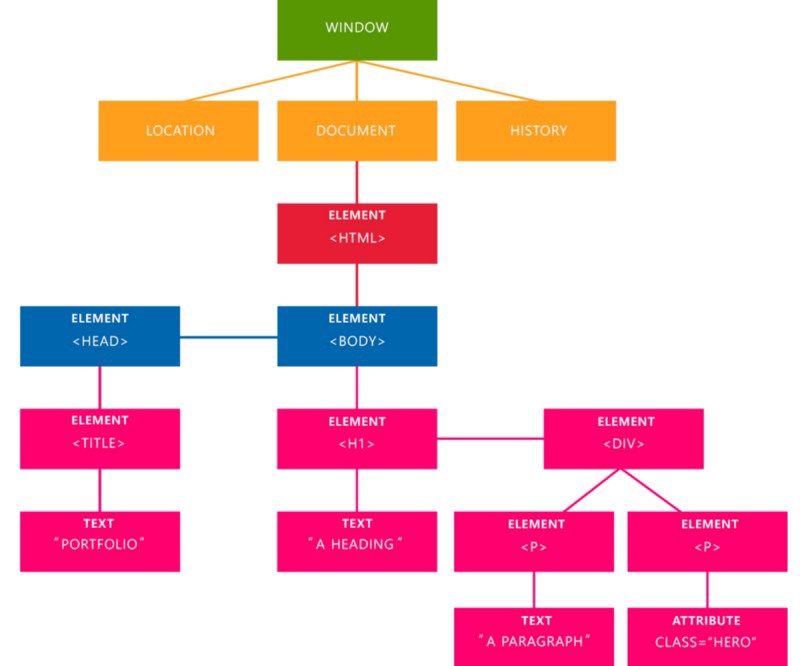

The Document Object Model (DOM) is a programming API for HTML and XML documents. The document object represents the whole html document.

When html document is loaded in the browser, it becomes a document object. It is the root element that represents the html document. It has properties and methods. By the help of document object, we can add dynamic content to our web page.

After the browser reads your HTML document, it creates a representational tree called the Document Object Model and defines how that tree can be accessed.

In the image above, we can see the representational tree and how it is created by the browser. In this example, we have four important elements that you’re gonna see a lot:

Document: It treats all the HTML documents.

Elements: All the tags that are inside your HTML or XML turn into a DOM element.

Text: All the tags’ content.

Attributes: All the attributes from a specific HTML element. In the image, the attribute class=”hero” is an attribute from the "p" element.

-

-

The browser goes to the DNS server, and finds the real address of the server that the website lives on (you find the address of the shop).

-

The browser sends an HTTP request message to the server, asking it to send a copy of the website to the client (like you go to the shop and order your goods). This message, and all other data sent between the client and the server, is sent across your internet connection using TCP/IP.

-

If the server approves the client's request, the server sends the client a "200 OK" message, which means "Of course you can look at that website! Here it is", and then starts sending the website's files to the browser as a series of small chunks called data packets (the shop gives you your goods, and you bring them back to your house).

-

The browser assembles the small chunks into a complete web page and displays it to you (the goods arrive at your door — new shiny stuff, awesome!).

-

Once the client’s request is approved, the server first sends back the HTML (index) file — index.html is commonly named as such, as it is the first file of a website to be parsed by the server.

-

The HTML file can reference CSS and JavaScript, either in external files via "link" and "script" elements respectively, or embedded in the HTML page via "style" and "script" elements.

-

From a server standpoint it is important to know the order in which these files are parsed when the response is sent back:

-

The HTML file is parsed first and, by looking inside that file, the server recognises which CSS and JavaScript files are referenced.

-

After the HTML has been parsed and a DOM tree structure has been generated from it, the linked CSS is then parsed, and styles are applied to the appropriate parts of the DOM tree. At this point, the visual representation of the page is painted to the screen, and the user sees the page.

-

The JavaScript usually gets parsed and applied to the page after the HTML and CSS.

-

-

In modern websites, scripts are often “heavier” than HTML: their download size is larger, and processing time is also longer.

When the browser loads HTML and comes across a <script>...</script> tag, it can’t continue building the DOM. It must execute the script right now. The same happens for external scripts <script src="..."></script>: the browser must wait for the script to download, execute the downloaded script, and only then can it process the rest of the page.

That leads to two important issues:

Scripts can’t see DOM elements below them, so they can’t add handlers etc.

If there’s a bulky script at the top of the page, it “blocks the page”. Users can’t see the page content till it downloads and runs.

Luckily, there are two script attributes that solve the problem for us: defer and async.

The defer attribute tells the browser not to wait for the script. Instead, the browser will continue to process the HTML, build DOM. The script loads “in the background”, and then runs when the DOM is fully built.

The async attribute is somewhat like defer. It also makes the script non-blocking. But it has important differences in the behavior. async scripts load in the background and run when ready.

-

When building an application, sometimes you’ll need to attach event listeners to buttons, text, or images on the page in order to perform some action when the user interacts with the element.

If we take a simple todo list as an example, the interviewer may tell you that they want an action to occur when a user clicks one of the list items. And they want you to implement this functionality in JavaScript assuming the following HTML code:

<ul id="todo-app"> <li class="item">Walk the dog</li> <li class="item">Pay bills</li> <li class="item">Make dinner</li> <li class="item">Code for one hour</li> </ul>

You may want to do something like the following to attach event listeners to the elements:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { let app = document.getElementById('todo-app'); let items = app.getElementsByClassName('item'); // attach event listener to each item for (let item of items) { item.addEventListener('click', function() { alert('you clicked on item: ' + item.innerHTML); }); } });

While this does technically work, the problem is that you’re attaching an event listener to every single item individually. This is fine for 4 elements, but what if someone adds 10,000 items (they may have a lot of things to do) to their todo list? Then your function will create 10,000 separate event listeners and attach each of them to the DOM. This isn’t very efficient.

Here’s the code for event delegation:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { let app = document.getElementById('todo-app'); // attach event listener to whole container app.addEventListener('click', function(e) { if (e.target && e.target.nodeName === 'LI') { let item = e.target; alert('you clicked on item: ' + item.innerHTML); } }); });

Throttling will delay executing a function. It will reduce the notifications of an event that fires multiple times. Throttling enforces a maximum number of times a function can be called over time. As in "execute this function at most once every 100 milliseconds."

Debouncing will bunch a series of sequential calls to a function into a single call to that function. It ensures that one notification is made for an event that fires multiple times. Debouncing enforces that a function not be called again until a certain amount of time has passed without it being called. As in "execute this function only if 100 milliseconds have passed without it being called."

Throttle (1 sec): Hello, I am a robot. As long as you keep pinging me, I will keep talking to you, but after exactly 1 second each. If you ping me for a reply before a second is elapsed, I will still reply to you at exactly 1 second interval. In other words, I just love to reply at exact intervals.

Debounce (1 sec): Hi, I am that ^^ robot's cousin. As long as you keep pinging me, I am going to remain silent because I like to reply only after 1 second is passed since last time you pinged me. I don't know, if it is because I have an attitude problem or because I just don't like to interrupt people. In other words, if you keeping asking me for replies before 1 second is elapsed since your last invocation, you will never get a reply. Yeah yeah...go ahead! call me rude.

-

Whenever a function is invoked, a new scope is created for that call. The local variable declared inside the function belong to that scope – they can only be accessed from that function -. It’s very important to understand that before moving further.

Remember:

- The function scope is created for a function call, not for the function itself

2)Every function call creates a new scope

When the function has finished the execution, the scope is usually destroyed.

function buildName(name) { var greeting = "Hello, " + name; return greeting; }

The function buildName() declares a local variable greeting and returns it. Every function call creates a new scope with a new local variable and after the function is done executing, we have no way to refer to that scope again, so it’s garbage collected.

But how about when we have a link to that scope? Let’s look at the next function:

function buildName(name) { var greeting = "Hello, " + name + "!"; var sayName = function() { var welcome = greeting + " Welcome!"; console.log(greeting); }; return sayName; } var sayMyName = buildName("John"); sayMyName(); // Hello, John. Welcome! sayMyName(); // Hello, John. Welcome! sayMyName(); // Hello, John. Welcome!

The function sayName() from this example is a closure.

A closure is a function which has access to the variable from another function’s scope. This is accomplished by creating a function inside a function. Of course, the outer function does not have access to the inner scope.

The sayName() function has it’s own local scope (with variable welcome) and has also access to the outer (enclosing) function’s scope. It this case, the variable greeting from buildName().

After the execution of buildName is done, the scope is not destroyed in this case. The sayMyName() function still has access to it, so it won’t be garbage collected. However, there is not other way of accessing data from the outer scope except the closure.

This is the big gotcha of the entire concept. The closure serve as the gateway between the global context and the outer scope. I cannot access directly variables from the outer scope if the closure is not allowing it. This way, I can protect the variables from the outer scope. They are – by all means – private and the closure can serve as a getter or setter for them.

Remember:

-

Closure are nested function which has access to the outer scope

-

After the outer function is returned, by keeping a reference to the inner function (the closures) we prevent the outer scope to be destroyed.

Another extremely important thing to understand is that a closure is created at every function call. Whenever I’m using the closure, it will reference the same outer scope. If any variable is change in the outer scope, than the change will be visible in the next call as well.

function buildContor(i) { var contor = i; var displayContor = function() { console.log(contor++); contor++; }; return displayContor; } var myContor = buildContor(1); myContor(); // 1 myContor(); // 2 myContor(); // 3 // new closure - new outer scope - new contor variable var myOtherContor = buildContor(10); myOtherContor(); // 10 myOtherContor(); // 11 // myContor was not affected myContor(); // 4

-

An immediately-invoked function expression (IIFE) immediately calls a function. This simply means that the function is executed immediately after the completion of the definition.

(function() { console.log('Welcome to the Github.'); }());

-

Avoiding pollution in the global namespace.

-

Variables defined in IIFE (or even any normal function) don't overwrite definitions in global scope.

-

Protecting code from being accessed by outer code.

Everything that you define within the IIFE can be only be accessed within the IIFE. It protects code from being modified by outer code. Only what you explicitly return as the result of function or set as value to outer variables is accessible by outer code.

-

Avoid naming functions that you don't need to use repeatedly. Though it's possible to use a named function in IIFE pattern you don't do it as there is no need to call it repeatedly, generally.

-

For Universal Module Definitions which is used in many JS libraries. Check this question for details.

-

-

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(function(location) { console.log(location.coords.latitude); console.log(location.coords.longitude); console.log(location.coords.accuracy); });

-

In software engineering, a design pattern is a reusable solution for commonly occurring problems in software design. Design patterns represent the best practices used by the experienced software developers. A design pattern can be thought of as a programming template.

Using an appropriate design pattern can help you to write better and more understandable code, and the code can be easily maintained because it’s easier to understand. Most importantly, the design patterns give software developers a common vocabulary to talk about. They show the intent of your code instantly to someone learning the code.

- It’s a reusable solution that can be applied to commonly occurring problems in software design.

- Patterns are proven, expressive, reusable and offer value.

- Code becomes more expressive, encapsulated & structured.

- When creating or maintaining solutions, one of the most powerful approaches to getting all developers or teams of your organization on the same page is creating Design patterns.

- One of the most important aspects of writing maintainable code is being able to notice the recurring themes in that code and optimize them.

Some examples are design patterns are - Module Pattern, Constructor Pattern, Singleton Pattern, Observer Pattern etc.

-

Modules should be Immediately-Invoked-Function-Expressions (IIFE) to allow for private scopes - that is, a closure that protect variables and methods (however, it will return an object instead of a function). This is what it looks like:

(function() { // declare private variables and/or functions return { // declare public variables and/or functions } })();

Here we instantiate the private variables and/or functions before returning our object that we want to return. Code outside of our closure is unable to access these private variables since it is not in the same scope. Let’s take a more concrete implementation:

var HTMLChanger = (function() { var contents = 'contents' var changeHTML = function() { var element = document.getElementById('attribute-to-change'); element.innerHTML = contents; } return { callChangeHTML: function() { changeHTML(); console.log(contents); } }; })(); HTMLChanger.callChangeHTML(); // Outputs: 'contents' console.log(HTMLChanger.contents); // undefined