Last Update: March 26th, 2019

Alex Russell

<slightlyoff@google.com>

Adam Argyle<argyle@google.com>

Never-Slow Mode ("NSM") is a mode that sites can opt-into via HTTP header. For these sites, the browser imposes per-interaction resource limits, giving users a better user experience, potentially at the cost of extra developer work. We believe users are happier and more engaged on fast sites, and NSM attempts to make it easier for sites to guarantee speed to users. In addition to user experience benefits, sites might want to opt in because browsers could provide UI to users to indicate they are in "fast mode" (a TLS lock icon but for speed).

Browsers could also gate the availability of some features that developers may want access to (note that these are hypotheticals, not concrete proposals).

Feature Policies are a relatively new web platform feature that allow sites to disable certain web platform features at runtime. They help prevent inadvertant use of known-slow patterns and allow sites to control or disable use of certain powerful features. NSM is itself a Feature Policy that bundles together several existing Policies and adds a new approach to resource budgeting that the Feature Policy framework does not yet support.

NSM is designed to keep pages responsive, so limits apply only to a document's main thread. Limits do not apply to Web Workers, Service Workers, and Worklets. NSM tries to budget only what is scarce, so resources loaded from Service Worker Cache Storage are not deducted againt size limits.

Policy violations can be logged via the Reporting API, and a "report only" mode is proposed to enable sites to transition gradually.

NSM differs from other Feature Policies in several ways. First, limits are set on a per interaction basis, meaning that user engagement (tap, click, scroll) creates more budget. Second, NSM is only available to be set via HTTP header. That is, a document cannot enable NSM for iframes without their consent.

- Uniform, objective, consistent criteria

- A single set of resource and runtime restrictions that ensure responsive content on 90+% of devices and networks

- Edit/refresh-cycle error reporting. Developers should know their site is compatible when published and rely on the browser to keep violations (e.g., by third parties) from ruining the user experience

- Server-side awareness. Pages that opt-in to NSM (or browsers that have enabled it on the user's behalf) should inform servers so they can send conforming content

- Compatibility with existing content. Like TLS, most sites will need to do work to become NSM-compatible

- Flexibility is a non-goal. A single set of rules enables the entire ecosystem to easily understand what is "in" and what is "out", without resorting to complex multi-party budgeting

- Global or page-level budgets. Budgets are set per-document to ensure predicability for developers. Global budgets are difficult to reason about, particularly in the presence of

<iframes>. NSM seeks to strike balance between resource limit absolutism and developer agency

Like other Feature Policies, NSM is enabled by pages through an HTTP header.

Feature-Policy: allow-slow 'none'; geolocation 'none'

This policy disables geolocation for the document and turns on NSM for the document and all descendant <iframe>s that also opt-in. <iframe>s that do not also opt-in are not loaded.

Note: the security implications of policy application to content which does not itself opt-in are discussed in detail later but the TL;DR is that NSM differs from other Feature Policies in this respect and that limits are set per document.

Policy violations can be automatically logged to an endpoint by adding the approprite Reporting API header:

Feature-Policy: allow-slow `none`; report-to allow-slow-reports

Report-To: { "group": "allow-slow-reports",

"max_age": 10886400,

"endpoints": [{ "url": "https://example.com/allow-slow-reports" } ] }

The same errors will be delivered to a ReportingObserver.

A variant of the mode is possible for sites that do not want browsers to enforce conformance, but instead are attempting to collect violation logs to understand what's involved in becoming NSM-conformant. The following policy logs errors to the same endpoint but does not modify content:

Feature-Policy: report-only-allow-slow; report-to allow-slow-reports

Report-To: { "group": "allow-slow-reports",

"max_age": 10886400,

"endpoints": [{ "url": "https://example.com/allow-slow-reports" } ] }

The heart of NSM is a set of policies derived from experience analysing hundreds of sites. Common pitfalls cause well-meaning sites to deliver poor experiences. The numbers proposed below are subject to revision, but the need for limits on each dimension is clear.

The following changes are made to default Web Platform behavior to ensure that NSM content performs well:

document.write()in the same document is disabled (it may be re-enabled for cross-frame use)- Synchronous XHR is removed

- Web Fonts are fetched eagerly and do not block layout if they take more than 500ms to load

NSM sets the following limits per-interaction. Each navigation is considered an interaction, as are subsequent taps and scroll gestures. This ensures that NSM does not incidentally favor multi-page sites over Ajax-based interaction. We derive this from the insight that "plain HTML" GMail and "regular" (Ajax) GMail do the same semantic things, only in different ways. A uniform accounting method enables developers to decide which mechanism works best for their application.

To enforce size limits in the face of resources served without valid Content-Length headers, NSM buffers budgeted resources which do not declare their length. Hopefully this provides developers with an incentive to include Content-Length headers on critical responses.

Note: main-document content (HTML) is not subject to size budgeting or buffering. Sites that inline resources do not need to worry about the sizes of those resources.

Limits are enforced against the wire size of a resource. That means a 50 KiB limit for JS may correspond to more than 300 KiB on-disk. That's a lot of code!

Note: all budgets are subject to revision. Where helpful, the rationale for each is provided.

This table summarizes the provisional per-interaction limits; discussion of each follows:

| Type | Per-Resource Limit | Cumulative Limit | Scope |

| Connections | n/a | 10 | document |

<iframe> |

n/a | 10, depth 2 | global |

| Script | 50 KiB | 500 KiB | document |

| External Stylesheets | 100 KiB | 200 KiB | document |

| Web Fonts | 100 KiB | 100 KiB | document |

| Images | 1 MiB | 2 MiB | document |

| Main-thread Execution | n/a | 200ms | document |

Documents are limited to 10 new connections per interaction.

This is not strictly a limit on the number of origins that may be consulted in the construction of a document, as HTTP/2 allows for connection coalsecing.

In practical terms, this means that sites should attempt to host as many of their resources as possible from a single origin and explicitly budget connections for third parties.

Rationale: poorly-constructed documents frequently spend large amounts of time in the critical path in DNS/TCP/TLS handshaking for sub-resources hosted on other origins. This effect is most pronounced on the slowest networks. In an HTTP/2 world this is an anti-pattern and should be discouraged.

NSM places a global (per tab) limit on the total number of <iframe>s (at any depth) of 10 and limits <iframe> depth to 2.

Each <iframe> document has it's own budget allocation for all of the following resource limits so. That means a document with a single <iframe> can globally load double the amount of script, CSS, fonts, etc. Each document, however, continues to be limited by the budgets noted below.

Rationale: <iframe> elements are heavyweight, so limiting their number is critical in memory-constrained environments. Deeply nested iframes often indicate badly-behaved dynamic composition (e.g. ad "wormholes").

JavaScript and WASM modules are limited to 50 KiB per-resource and a total per-interaction limit of 500 KiB within a document.

Rationale: script execution frequently blocks the main thread. Large scripts evaluate as a single block, preventing interactivity. Breaking scripts into smaller chunks helps to ensure the document remains responsive. 50 KiB of script on the wire can be as much as 300-450 KiB of uncompressed script. This much content can easily lock up the main thread for more than 200ms on a slow device, so setting the limit higher carries risk of creating more "dishonest pixels" and letting developers run afoul of runtime limits (see below) too easily.

Note: budgets are not applied to scripts loaded into Service Workers, Workers, or Worklets as they cannot block main-thread interactivity. Sites wishing to do heavy computation can adopt NSM by moving heavy work into Workers.

Some early feedback on this limit from developers cites the pervasiveness of scripts larger than this limit. There are several reasons to be skeptical of these claims.

First, manually inspected bundles appear to include a great deal of polyfill overhead, nearly all of which is unneccessary on modern browsers. Services like polyfill.io make it simple for sites to avoid sending this bloat to users who do not benefit from it. Tools like the prpl-server exist to make these decisions server-side for those uncomfortable delegating these decisions.

Next, many bundles appear to include all of their libraries served as a single resource, reducing cacheability.

Lastly, many frameworks and toolkits easily fit within the 50 KiB per-resource wire-size budget, including React + ReactDOM, Vue.js, LitElement, Polymer, and jQuery.

CSS stylesheets are limited to 100 KiB per-resource and a total per-interaction limit of 200 KiB.

Rationale: In automated build tools, stylesheets can often grow to many hundreds of KB without teams noticing. The limits applied here are enough for nearly all reasonable layouts when using modern CSS features.

Web Fonts are limited to 100 KiB per-resource and a total per-interaction limit of 100 KiB.

Rationale: Web Fonts are often heavyweight. In conjunction with eager loading, low size limits prevent fonts from blocking access to otherwise-usable content.

Images are limited to 1024 KiB (1 MiB) per-resource and a total per-interaction limit of 2048 KiB (2 MiB) within a document.

Rationale: 1 MiB is large enough to encode a screenshot of nearly all above-the-fold sites on most resolutions and screens using modern compression. Resources larger than this are generally errors.

Main-thread script execution must be broken up in order for documents to remain responsive. Ideally, work is scheduled in chunks that are not longer than 8-10ms. Many systems today create single tasks that are many orders of magnitude larger than this, creating a situation in which content may be visible, but cannot be interacted with. This is sometimes referred to as the "dishonest pixel problem": the site appears to allow you to do something, but attempting to use it fails until long script tasks complete.

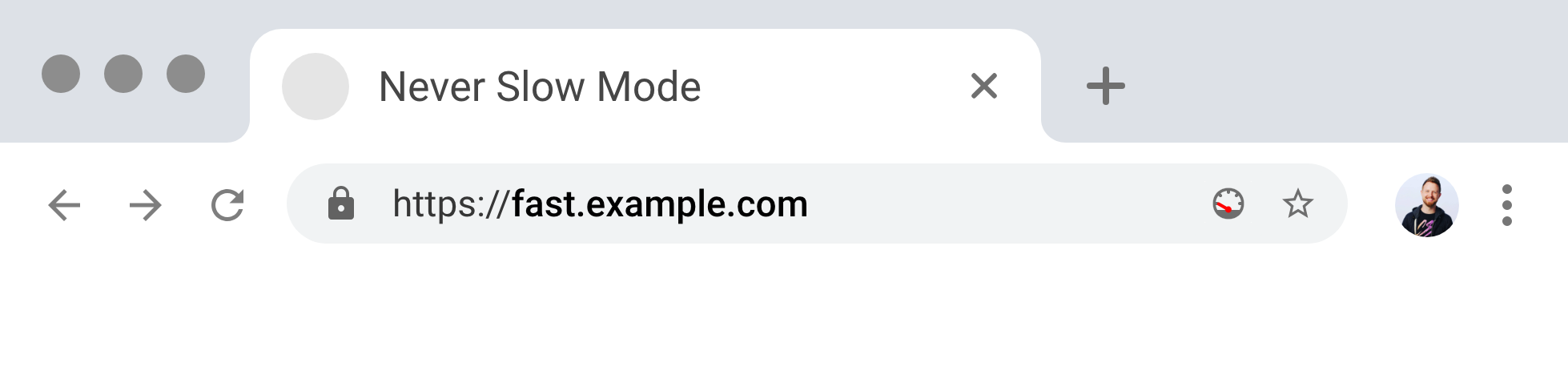

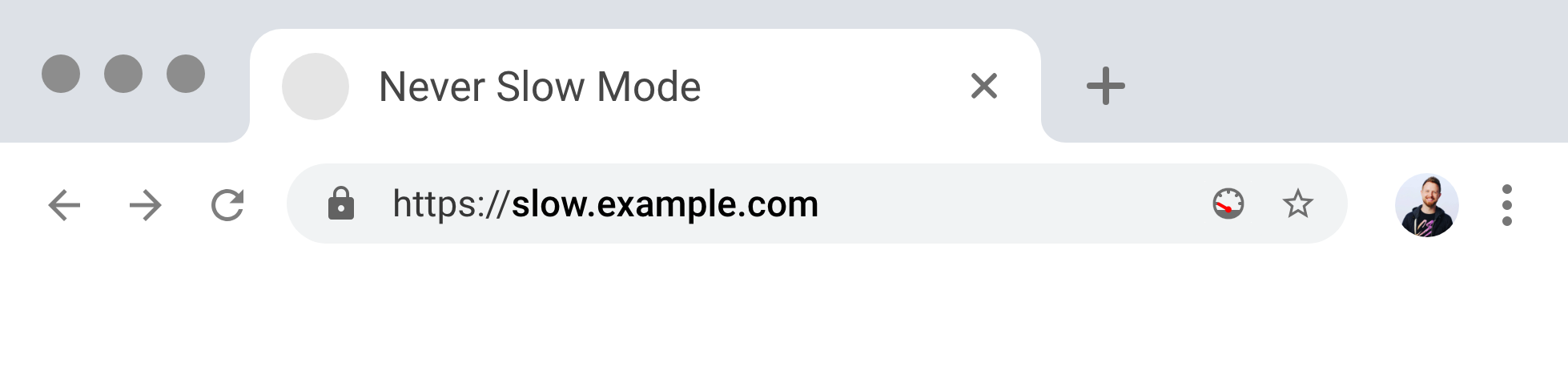

To discourage dishonest pixels, NSM caps the length of tasks. As it isn't possible to safely interrupt JS tasks, NSM UI indicators will flag non-compliance and violation reports will be triggered when a main-thread JS task takes longer than 200ms.

Becomes:

Note: the long-task limit is by far the most contentious limit. It has the most open questions associated with it, both in terms of predictability for developers across the fleet of user devices and a browser's ability to communicate meaningfully to users about violations. Expect changes to, or removal of, this limit!

The limits described above may seem low to developers not explicitly targeting growth markets. Even teams that work to set performance budgets struggle to enforce them over time, particularly in the face of changing business priorities and team churn.

So why would anyone ever opt into NSM?

Motivated teams turn on NSM to provide guardrails, ensuring that third parties and developers within their teams do not stay from the golden path. Experience teaches that only a small minority of sites tend to adopt this sort of guardrail.

The recent increase in TLS adoption suggests other reasons sites may chose to opt-in to NSM.

Note: all of the following are hypothetical. None are concrete plans nor should they be misconstrued as such.

Many Feature Policies exist today, but it is hard to understand what combination of them will guarantee good performance. Like opting into TLS, opting into NSM declares to runtimes that a page intends to be fast. This single, global contract turns a complex space with many options and difficult choices into a binary state that can be reflected back to users. Some detail is elided, but users can put their trust in UAs to enforce the contract. Without such a contract, enforcement must happen with interventions at the margins. This has proven to be extordinarialy difficult in practice.

Browsers started the transition to an encrypted web from a similar place: the wrong default. UI surfaces tacitly condoned insecure sites instead of warning users about them. Recognizing this was backward, they worked to flip the default in many small increments. At the end of the transition, browsers will eventually cease to tell users about connection state _unless something is wrong._ That is, secure connections should be the default.

The same is true with performance.

Today's browsers tacitly condone terrible performance, however we're starting from an even worse position; no browser today has a reliable signal against which to let users know that a site is fast (let alone slow). NSM provides such a signal in much the same way that the introduction of SSL/TLS in browsers created the opportunity to badge some sites as secure. In the short-run this will let browsers show users that certain sites are opting into delivering a good experience. In the long run, this enables the same default flip. At some date in the far distant future, perhaps only sites that don't opt in will receive "slow site" warning UI.

Content discovery engines also eventually preferred TLS-encrypted sites, and could do the same for NSM versions of content, badging UI in a similar way to help guide users toward sites that are known to be fast. Importantly, NSM decouples the question of speed from any specific technology. Any tool, framework, or approach can be used so long as limits are not violated.

Many systems today spend large amounts of server-side resources to capture a "snapshot" of a URL to provide a rich summary in a social media setting. Similarly, many web crawlers now run JavaScript. Collectively, these systems do not know how "heavy" a page is until it is being run, causing them to frequently take shortcuts or to reduce the frequency with which they take updated snapshots of content.

Sites that opt-in to NSM provide a valuable signal to these backends, allowing them to safely crawl them at a much faster rate, allowing site developers to reach a broader audience with higher-quality content.

In recent years, many web platform features have become gated on TLS opt-in. We can imagine browser vendors taking a similar stance with regards to new features and NSM: only sites which demonstrate that they are willing to prioritize user experience might continue to be able to request certain permissions (e.g., Push Notifications) or access upcoming features.

Progressive Web Apps are designed around a set of criteria designed to help deliver high-quality experiences. Until now, they have not mandated specific runtime performance guarantees. One can imagine PWA listing in app stores and inline PWA installation being gated on sites opting into NSM. One might even imagine that NSM could be forced on for these apps post-install to ensure policy conformance.

An extreme version of existing browser Data-Saver features could perhaps opt known-compatible sites into NSM on the user's behalf without developer cooperation. Such a mode would need to broadcast the NSM policy to the server in a header, creating privacy considerations. The extent to which one extra bit of metadata is indicative of anything meaningful is an area of active debate.

We can imagine an HTTPS Everywhere-like extension or browser mode opts users into NSM for content which may not be fully aware or prepared to operate under its constraints. Such situations create risks of side-channel attacks (see below). In order to avoid them, we can imagine adding an opt-out that explicitly puts a page into slow-mode:

Feature-Policy: allow-slow '*'

Auto-opt-in modes create challenges for developers who may want to negotiate support for NSM. To support this, such modes may wish to send the existing Save-Data header to inform sites of the policy to be applied, potentially allowing them to opt out or serve different (known compatible) content.

NSM generally avoids global limits. Budgets that span multiple documents at the same time are difficult for developers to build to. If, for instance, a global budget of 1 MiB of script were enforced, but any <iframe> in the document hierarchy could maliciously subtract from a budget, depriving a parent, peer, or child of critical functionality.

Global limits create situations in which a malicious parent can attack unwitting children (see next section).

The only limits which are global in NSM are restrictions on the total number of <iframes> and their depth. All other policies are budgeted per document. That is, if a parent document contains two <iframe>s, the total amount of compressed script allowed to be loaded over the wire is 1.5 MiB, rather than 500 KiB, as each document is allowed a maximum of 500 KiB.

The <iframe> depth and count limits expose a new bit of information to documents: the total number of sibling frames. The depth in the tree of a document would be exposed if the cap on depth were greater than 2.

It is TBD as to the reasonableless of these limits and if they create new hazards.

To prevent inadvertant creation of side-channels and violated content expectations, NSM requires sub-documents also opts-in, else they do not load. This is similar to X-Frame-Options, but with the default flipped to deny. This has several implications.

- Correspondence between Feature Policy headers and

<iframe allow>attributes is not respected. Parent documents which setslow-mode 'none'implicitly require that all sub-documents do the same. Those that do not are not loaded. - Child frames that opt in do have limits enforced, except for

<iframe>count and depth limit which cannot be global without top-level-document opt-in.

A concern with size budgets is the potential of malicious third parties to strategically exhaust budgets to learn things they should not know about the state of the document. NSM avoids this issue for resources loaded in other frames by enforcing budgets on a per-document basis. This leaves concerns about resources directly included by potentially mischevious document or in the presence of mischevious third party resources. This concern arises for resources which themselves have not opted into sharing their content with the document, but are composed into it. Primary examples include the content and metadata of cross-origin images, styles, and scripts.

The Web Platform's Cross-Origin Resource Sharing ("CORS") mechanism is highly complex in practice due to the need to continue to support this pre-CORS content and the inability of browsers to reliably know which reachable servers are private or public.

The platform currently attempts (with varying success) to withhold the following about non-CORs'd resources composed into a document:

- Images: pixel data (the exact contents that are rendered), exact byte size and dimensions (likely leaked by timing and sibling layout via replaced content layout)

- Scripts: script text and size

- Styles: URLs of nested

@import-included stylesheets

Most other media types have been specified to require CORS to function cross-origin, which means the platform does not need to gaurantee opacity for their contents.

One concern about NSM is that exact-byte-budgets may expose information about the otherwise-opaque resources. The worst-case scenario is that of a malicious top-level page, as it can:

- Run whatever code it likes

- Include arbitrary CSS to affect and respond to layout

- Control the sizes of all other resources in the document

- Control the ordering and timing of resource loads

- Control the exact URLs of included resources

- Affect or control the cache state of included resources

Documents can observe a great deal about resources loaded into them with this level of control. As a result, NSM may leak information about the size of resources, either through load timing or layout channels. This could be meaningful in establishing a user's logged-in state from the size of particular images in browsers that do not double-key their caches.

Developers, obviously, should not be serving sensitive resources without explicit CORs headers. The extent of the potential problems introduced is unclear, however, several mitigations are possible if it is deemed impossible to convince developers or browsers to change their default behavior:

- Adopt a CORS-only requirement for NSM documents. Such a mode does not yet exist in the platform, but is being discussed with regards to other features such as threads for Web Assembly

- Fuzzy budgeting. In this variant, budgets may be exact at development time but may be adjusted by random amounts at runtime. Similar fuzziness has been introduced for size information related to opaque objects stored on the filesystem

We hope security professionals can guide us to adopt the correct policy.

It could be reasonable to allow the usual Feature Policy syntax for allowing specific sites to be opted-out of NSM in iframes, e.g. loading a page from https://slow.example.com:

Feature-Policy: allow-slow 'self' https://example.com https://other.com

<html>

<head><!-- page from https://slow.example.com --></head>

<body>

<!-- allowed by 'self' -->

<iframe src="./slow.html"></iframe>

<!-- allowed by origin policies -->

<iframe src="https://example.com/"></iframe>

<iframe src="https://other.com/deep/link.html"></iframe>

<!-- blocked unless iframe content send NSM opt-in header -->

<iframe src="https://blocked.example.com"></iframe>

</body>

</html>This policy still applies limits to the top-level document. It selectively allows them to be relaxed for sub-frames, however. We can imagine a UI indicator state that's "neutral" in these cases:

Several things recommend this approach:

- Enables sites to adopt NSM incrementally

- Provides a way to isolate poorly behaving third parties

- Prevents NSM's syntax from being an "oddball" within the Feature Policy grammar

This would open several questions regarding iframe policy application, but in general, may be the right way forward.

This hardly needs saying given the authors of this proposal, but it's a clear aspiration to desribe all of the policies enforced by NSM in terms of well-layered APIs. In particular, the allow-slow 'none' policy should desugar well to a set of other Feature Policies.

The goal of NSM isn't to create a brand new, stand-alone set of policies, but rather to wrap-up existing (or to-be-developed) policies into a binary opt-in. To the extent that NSM implements policies that FP don't provide yet, our goal is to re-introduce them to FP directly (although this does not block NSM progress).

A long-task limit of 200ms may be difficult to build to reliably from the perspective of a fast developer device. Many developers are unfamiliar with the performance diversity of today's market where most global device shipments of all computers are Android devices, all of which are slower than competing iOS devices and laptops. 200ms of single-core-bound JS exec on a fast dekstop Intel chip may equate to more than 2s of time on an entry-level Android device or a top-of-the-line smartphone.

Should long-task limits, therefore, be lower on faster CPUs? How should that scaling be calculated? Should the be linear or should devices be put into fewer, broader buckets?

Predictability questions also arise from system state, which a developer cannot control. A site that mostly stays under the long-task limit on a particular device may find its expectations violated by thermal throttling (very common on smartphones) or competing tasks (e.g. background software updates).

To attack the predictability problem of background work, implementations could measure only the self-time of a task, rather than wall-time. To tackle thermal throttling, implementations could become frequency and throughput aware, but this is fraught given the pervasiveness of ever-more-sophisticated dynamic workload scheduling across heterogenous cores.

One area of flexibility available to implementations is to lift enforcement and limits in the face of ambiguity, perhaps running strict enforcement at development time and on known-fast devices, while reducing likelyhood of strict enforcement in the face of more variability factors. Enforcement flexibility could be combined with violation reporting (that is, tell the developer but not the user) to help developers improve.

More research is needed.

While the proposed limits have been taken from extensive experience with real-world sites on a diversity of hardware, the plural of anecdote is not data. It is an open research question to ground the proposed limits in HCI perceptural limits and grounding for which devices and network are actually at the P90 mark. E.g., if P90 for networks is 2G (rather than the suspected 3G), perhaps the limits should be set lower.

Similarly, if the result of ongoing RUM studies into First Input Delay indicate (as is likely) that many long tasks do not block interaction — perhaps because input is gated on not-yet-generated UI, or because input is attempted late in the task, or because developers get creative — the limit for long tasks proposed here may be far too low.

The proposed system does not impose any limits on resource loading or processing within workers. The intuition at work is that Workers, while perhaps CPU-hogging, are not in the user's critical path for interactivty. OS and browser schedulers can prioritize input response, even in core-limited environments.

The current proposal also places no limits on the number of workers that can be created per interaction, nor the total number of workers. Perhaps these decisions can be revisited?

Memory pressure is a key determinant of runtime performance at the low-end, however NSM doesn't directly budget RAM. This is due, in part, to the difficulty of understanding memory from the web developer perspective. In addition to being a GC'd environment, developers often have little control over which operations will allocate. Browser graphics stacks in particular are prone to implicit allocation and copies of large amounts of data. Since this isn't under direct developer control (or even observation), NSM doesn't set limits other than browser OOM.

Thankfully OOM is something some browsers are beginning to report to developers.

On limited devices (e.g., the emerging class of "smart feature phones"), the existing web is barely functional. For users enduring these constraints, opting into an "extreme" version of Data-Saving modes that turn on NSM by default could have the effect of making a large fraction of otherwise-unusable web content more bearable.

Similarly, content discovery engines and large sites may want to place limits on their outbound links. Presumably they can validate the extent to which destination URLs work (or don't) with NSM applied.

Both of these options represent a form of external opt-in. Instead of web developers applying NSM to their own content, users could experience arbitrary sites with the proposed policies applied unilaterally. This could be done with extension to links e.g.:

<a href="https://example.com" rel="neverslow">Example</a>Such a rel type could allow browsers to decorate links to NSM-enabled pages with iconography noting their speed, similar to iconography in a browser's URL bar for sites that opt-in to NSM. This is difficult to achieve today as browsers have only probabilistic (at best) understanding of destination performance and, sans NSM, no way to guarantee good behavior on the part of both first and third parties.

Note: this mechanism for applying NSM to non-opt-in content is related to top level navigations, rather than

<iframe>s. This removes the potential for malicious parents attacking child frames to leak information, but likely requires more security analysis.

TODO(slightlyoff): graphics illustrating possible visual treatement

To make such a mode liveable for developers of sites loaded under NSM this way, browsers can add several behavior changes to NSM applied in this way.

- The

Save-Dataclient hint should be sent with all such requests. As a large fraction of users already send this header to servers thanks to data saving browser modes, this does not meaningfully add to the fingerprinting surface. - More controversially, Client Opt-In variants of NSM could perhaps turn on a large set of Client Hints by default. This would help sites adapt to NSM without needing to remember to turn on

Accept-CHheaders explicitly, but may trigger privacy risks.

Setting global resource budgets for the entire frame tree was considered but was rejected for previous reasons concerning security and predictability.

Linters are valuable because they provide directness of action. Developers can see what constraints are violated within the edit-refresh cycle. This increases predictability which improves speed of iteration and reduces learned helplessness. NSM seeks to provide these benefits, but with additional runtime gaurantees that improve predictability.

Approaches that did not enforce runtime limits were considered, and may be part of a developer's workflow in an NSM-compliant world, but were judged insufficient without runtime enforcement because:

- Lint-only solutions do not easily constrain third parties, particularly dynamic third parties like ad networks. Linters also need a runtime component to detect and report RUM exceptions to rules. Hopefully NSM can be valuable as a runtime counterpart to development-time linting

- Lint-only solutions don't provide browsers and other runtimes with strong signals that content is expecting to be constrained, removing their ability to reflect state back to users

The report-only NSM mode functions as a linter, but is expected not to have much impact without a corresponding enforcement variant.

Solutions that transparently transform content can improve quality (e.g., mod_pagespeed). However, these solutions typically require relatively invasive server-side integration, which is more difficulty to deploy. This naturally reduces the deployability and short-term reach of these solutions.

Server-side solutions are also unlikely to be able to fully constrain third parties. This re-introduces significant sources of unpredictability for both developers and users.

Server-side tranformations are likely to help sites transitioning to NSM conformance, but like linters, are likely to be more valuable in conjunction with NSM and related external incentives than without.

A previous iteration of this proposal sought to pause future tasks when long-task limits were breached. This creates risks of "breaking apps" for transient reasons (hot devices getting thermally throttled, external-app CPU contention, etc.). Moving to a UI-indicator-change model aligns NSM with TLS's experience without removing possible pausing violation intervention in non-browser contexts (e.g., crawlers, PWA install gates).

NSM is an attempt to package up the brilliant work of many other projects in the hopes to make them more accessible. The proposal would not be possible without Ian Clelland, Ojan Vafai, and Ilya Grigork's work on Feature Policies and Interventions.

NSM is inspired by the outrageously effective partnership between Mozilla, Chrome, and others to encourage wide-scale adoption of TLS in recent years, particularly the efforts of: Emily Schechter, Emily Stark, Mike West, Adrienne Porter-Felt, Yan Zhao, Brad Hill, Martin Thomson, and J. Alex Halderman.

The work of Doantam Phan has helped to shape our view of what is most effective and his feedback on this proposal has considerably improved it.

Thanks to Andrew Betts, Andy Davies, and Josh Karlin for their eagle-eyed and constructive feedback, particularly on the shape of the API and security implications.

Thanks also to colleagues working in NBU and Chrome's Data-Saver projects whose feedback has directly changed the proposal, including: Tal Oppenheimer, Ben Greenstein, Annie Sullivan, and Kenji Baheux.

Folks working in web performance have had a huge impact on the thinking behind the proposed policies. In no particular order, thanks to: Shubie Panicker, Tim Dresser, Jake Archibald, Bryan McQuade, Yoav Weiss, Houssein Djirdeh, Addy Osmani, Dion Almaer, and Kristofer Baxter.

Lastly, the example of Malte Ubl and the AMP team have helped underscore the need for development-time-applicable policies and linting, highlighting the need for directness of action.