SID chip tunes are a block of 6502 code and data which actually run on a Commodore 64 or an emulator. Rather than try to squeeze a 6502 emulator on the AVR, Jetpack cross assembles the 6502 code to AVR assembler. Most of the 6502s 151 instructions are mapped to AVR assembler with writes the SID chip intercepted. Jetpack searches all execution paths to determine code block boundaries. Special cases are also implemented to deal with self-modifying code.

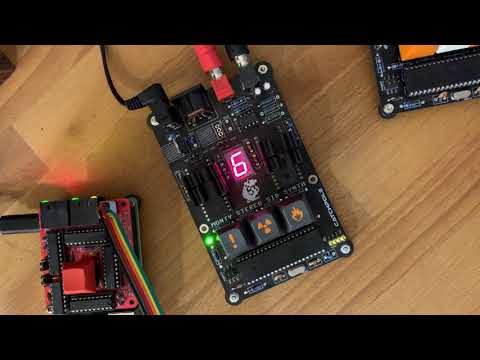

Jetpack was originally written to cross-compile a single SID, Monty On The Run,

so it can play on the Monty Stereo SID Synth. Other SIDs have been successfully converted.

https://github.com/slipperyseal/monty

Monty playing the Monty On The Run chip tune by Rob Hubbard...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i0d1r9NZg9I

Jetpak is written in go.

Jetpack loads SID files and writes the AVR assembler to standard out.

This assembler is compatible with avr-gcc.

go run jetpack.go Monty_on_the_Run.sid >motr.avr.s

See jetpack.go for command line options and their defaults.

For Jetpack to successfully convert a SID will depend on how the SID code works. Self-modifying code is the main issue. 6502 code might replace its own instructions in memory or immediate values loaded by instructions. AVR code exists in flash memory, not SRAM, plus the replacement of AVR code or data might not be practical solution anyway. These cases need to be identified and dealt with independently.

Jetpack currently detects the filename of Monty_on_the_Run.sid and

enables the special cases to convert this file.

The latest version of the output is included in the repo as motr.avr.s

The repo also contains the disassembled 6502 binary as motr.6502.asm.

This is handy when developing Jetpack and when comparing the cross-assembled output.

Jetpack also generates a memory map, a 256 x 256 pixels represent 64K of memory.

- Red: Translated code.

- White: Jump points within code. Target locations of JMP, JSRs and branch instructions.

- Dark Green: Data, padding, or unreachable code within the binary.

- Bright Green: Known data read and write points (which may have indexes applied).

- Dark grey: Eliminated code. Flattened jumps etc.

- Blue: 16x16 byte grid for your convenience.

-

Speed. Many instructions have a single instruction equivalent. For those that don't, the 6502 instruction often consumes several processor cycles anyway. While the AVR equivalent sometimes uses more instructions, each typically execute in 1 or 2 cycles. On average, it's probably faster than emulation.

-

Statically compiled simplicity. Assuming the cross-assemble was successful, no need not worry about dealing with an emulator. Emulation on AVRs with limited memory would still need to deal with a partial memory block, rather than the full 64K. This was the main driver for the project. Emulation might be more accurate, but the project was originally targeting one piece of code (not to mention it being a cool challenge).

-

Call functions direct from C.

-

Statically compiled. Unable to execute arbitrary code from SRAM.

-

Code density. 6502 code is much denser than the cross compile. For large code blocks emulation is perhaps preferred.

-

Can't cover all corner cases or self-modifying code that emulation can.

-

Not all opcodes supported. eg. JMP indirect, decimal mode, stack pointer instructions.

8367 A0 FF L8367 LDY #$FF

8369 AD FB 84 LDA $84FB

836C D0 06 BNE L8374

836E AD FC 84 LDA $84FC

8371 30 01 BMI L8374

8373 C8 INY

8374 8C FD 84 L8374 STY $84FD

8377 CA DEX

8378 30 03 BMI L837D

837A 4C 5F 80 JMP L805F

837D A9 FF L837D LDA #$FF

837F 8D FD 84 STA $84FD

8382 AD FB 84 LDA $84FB

8385 D0 05 BNE L838C

8387 2C FC 84 BIT $84FC

L8367: ldi r18, 0xff ; LDY #$ff

lds r16, ram+0x00fb ; LDA $84fb

tst r16

brne L8374 ; BNE $8374

lds r16, ram+0x00fc ; LDA $84fc

tst r16

brmi L8374 ; BMI $8374

inc r18 ; INY

L8374: sts ram+0x00fd, r18 ; STY $84fd

dec r17 ; DEX

brmi L837d ; BMI $837d

rjmp L805f ; JMP $805f

L837d: ldi r16, 0xff ; LDA #$ff

tst r16

sts ram+0x00fd, r16 ; STA $84fd

lds r16, ram+0x00fb ; LDA $84fb

tst r16

brne L838c ; BNE $838c

lds r20, ram+0x00fc ; BIT $84fc

mov r21, r20

and r21, r16

cln

clv

sbrc r20, 7

sen

sbrc r20, 6

sev

With each 6502 instruction represented as a single byte, often followed by a fixed size immediate value, it’s quite simple to decode the instructions.

Each 6502 instruction is represented with one or more AVR instructions that perform the equivalent operation.

We assign AVR registers to represent those of the 6502, the Accumulator, X and Y.

For many instructions there is a simple one-to-one equivalent. For others, multiple AVR instructions are required.

The AVR has instructions dedicated to loading and storing from memory, while algorithmic operations only operate on registers. The 6502 can perform algorithmic operations direct to memory and have indexed modes built directly into those instructions.

Where the translation becomes more nuanced is the interaction of status flags.

Code functions by the way status flags, such as zero, carry, minus and overflow, bringing state to subsequent instructions.

6502 instructions test some of these flags on load instructions, while the AVR instructions do not.

We also need to protect the carry flag while we use it to perform supportive operations which modify its state.

Static analysis can detect where status flags need to be tested or preserved, allowing those extra AVR instructions to be omitted.

"For subtractive operations, two (opposite) conventions are employed as most machines set the carry flag on borrow while some machines (such as the 6502 and the PIC) instead reset the carry flag on borrow (and vice versa)." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carry_flag

So yeah, AVR and 6502 use opposite conventions. Inverting the relevant branch instructions after a subtractive operation seems to work. More subtle cases across branches with different root instructions may be problematic.

Code and data are often found in the same binary. It’s not necessarily easy to know what is code and what is data. And of that data, which is read only and what is modified. Knowing this helps optimisation, of what can be stored in more abundant flash memory and what in more constrained SRAM. For data access, the 6502 has essentially 4 addressing modes (there are more specific modes, these are summarized):

- Immediate. Data is located with the instruction. Easy.

- Absolute address. Also easy. This relates to a specific memory location.

- Absolute address, indexed. We know the base address, but the index is a runtime value. Data could be within 256 bytes of this.

- Indirect, indexed, via pointers in zero page. zOMG! That could be anywhere.

It is assumed that we know the entry point of all code being called (this would be necessary even with emulation).

For SID files, the init and play addresses are supplied in the file.

Our first parse of the binary follows these code paths, marking a map of code points in a bitset.

We also store the jump and branch points (this is helpful when generating labels later).

Anything within the binary which is not code is assumed to be data.

This could be padding between code or actual data.

Absolute address writes into the identified code spaces tip us off to existence of self-modifying code.

The simplest solution is to cross assemble the code, which will be stored in flash, and then place the entire binary block, containing the 6502 code and data, in SRAM.

We don’t assume the AVR has 64k of SRAM.

Memory addresses have the base address of the binary block subtracted, reducing the memory space to effectively the size of the binary.

Using the code bitset could further help narrow the size of the binary block, excluding the unneeded 6502 machine code from it.

Or in the case of Monty On The Run we know that data starts at $8400, so we override that manually.

Writes to “zero page” (the first 256 bytes of RAM) are handled as a special case. Reads and write addresses to zero page are tracked to narrow memory requirements. There are indirect pointer instructions that allow placing pointers in zero page addresses. Often code will only use a small section of zero page for storing these indirect pointers.

Another optimisation is to flatten chained jumps. If a branch or jump simply points to another jump, the jump path is searched

for its final destination, and that location is substituted in the first branch or jump.

Its more common than you might think. Jump tables and where short range branches need to travel further, a branch to a long range jump is often used.

This flattening technique already eliminates a small code block from the start of Monty On The Run and optimises several branch instructions.

As another dimension to this challenge, 6502 code would often be self-modifying.

Code would swap out instructions or modify immediate instruction parameters which will be statically compiled for the AVR.

Monty On The Run has one piece of self-modifying code and currently it’s dealt with as a special case with custom AVR code.

Other cases where translation may not function correctly is where the 6502 code relies on specific behaviour of the processor.

For example, saving the status register and testing bits within it. While Jetpack can push and pop the status register to the stack,

it is the AVR status register, whose flags are in different locations. 6502 code which self-modifies jump or branch addresses

would also be a problem.

Jetpack also assumes all code paths are statically determinable. The Jump Indirect instruction is not implemented. Worst case, it would require a lookup table to map every 6502 RAM location to the AVR assembly location.