Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) is a practice recommended by many organizations, but the details of how to implement it are not clear. The basis of IaC are idempotent, declarative infrastructure templates written in a language such as ARM, bicep or Terraform organized in version control repositories such as Azure DevOps or GitHub. However, how to govern those repositories and control the deployment of those templates is an area where not much documentation exists.

There are some challenges common to all IaC domains, such as testing and validation of infrastructure templates before deployment. Additionally, Networking IaC (also called Network-as-Code, although NaC is an overloaded acronym in the networking industry) presents some specific problems due to the distributed nature of networking:

- Networking in Azure Landing Zones is distributed across the different landing zones and the centralized connectivity subscription

- The central network admin team typically has no knowledge of the specifics of each application, so it is down to the application owners to document those even if networking is not their main area of expertise.

This repo contains examples of different IaC approaches for Network-as-Code in Azure to solve the challenges described in the previous paragraphs. To illustrate different approaches and techniques this repo will focus on Azure network segmentation technologies, namely:

- Azure Firewall Policy: deployed centrally into the connectivity subscription where the Azure Firewall resides, but needs input from each workload (the firewall admin relies on the workload admins to define the rules required by each workload to work properly).

- Network Security Groups: deployed in a distributed manner in the workload's subscription, but needs shared rules required by compliance (for example, having an explicit

denyafter theallowrules).

This repo should be looked at as a collection of recipes that will help implementing certain aspects of the IaC toolchain. For that purpose, it contains multiple implementations to achieve the same goal (for example monorepo and multirepo, ARM and bicep, Azure Policy and in-pipeline scripts). Hence, it is not to be considered as a best-practices repo.

Some organization have traditionally centralized all networking configuration in a single team, the network admins. The most typical example is the administration of firewalls: in order to get a port open in the firewall, the application team needs to open a ticket so that the firewall configures the firewall accordingly. This approach suffers from many problems:

- The app team needs to wait until the firewall admin implement changes

- If there are many applications in an organization, the firewall team will just blindly implement whatever is asked (unless it goes against the company security policy), ending up in rules that open unnecessary attack surface

- The firewall team has no knowledge of whether the configured ports are really required, which ends up in most firewall configs being obsolete and overly complex with time

Ideally, each app team should be able to define their networking requirements with code, and these requirements would be converted in firewall configuration automatically. However, there has to be some control on how these networking requirements are defined, so there need to be some guardrails and validation to make sure that the organization security policies are complied with.

The first decision that every IaC (or actually DevOps) architect needs to take is whether (infrastructure) code is going to be arranged in a single repository for the whole organization, or distributed in different repositories owned each by a different application team. In essence, in a monorepo design all IaC templates will be in the same version control repository, while in a multirepo design each workload has its own repo. There are multiple aspects to consider when deciding to go for either monorepo or multirepo, here is a brief summary:

| Monorepo | Multirepo | |

|---|---|---|

| Access permissions | Hard, since it needs to be done on a folder-by-folder basis | Easy, since it is done on a repo-by-repo basis |

| Building the templates | Easy, all the files in one repo | Complex, files across multiple repos need to be put together |

| Github workflow management | Hard, many different actions and workflows in one single repo | Easy, only workflows and actions relevant to one specific workload (and its environments) in any given repo |

Whether monorepo or multirepo is best for your organization depends on multiple things (such as how different departments interact with each other), but lately the industry seems to be converging to multirepo, having all workload-specific configuration (including NSG and firewall rules) in dedicated repositories.

This repo covers 4 apps, 3 of which are using the monorepo pattern, and the last one the multirepo pattern:

- app01, app02, app03: all configured in the same repo (this one, segmentation-iac)).

- app04: configured in a dedicated repo (segmentation-iac-app04).

This repo contains examples of both ARM and bicep. ARM is mostly included to show the additional complexity that ARM-based IaC generates, due to its more limited file processing capabilities as compared to bicep:

- ARM modularity is quite limited, and you can only define nested templates referring to URLs and not file paths

- ARM lacks functions to load JSON/YAML code into templates

This repo is not aiming to deliver a full discussion on different IaC approaches (for example, Terraform is not included), but just on highlighting how the support for certain functionality in your IaC language of choice can drive the complexity of the final repository design.

We will start the discussion with examples to deploy an Azure Firewall Policy in a monorepo design (with three workloads app01, app02, app03). As described earlier, the Azure Firewall policy is a resource that is centrally deployed in the connectivity subscription.

Azure Firewall has a 3-level hierarchy, with some rules and limits (see Azure Firewall Limits)that will determine the grouping:

- Rules: can be application- or network-based

- Rule collections (RC): one rule collection can only contain network or application rules, not both

- Rule collection groups (RCG): maximum 60 per policy, maximum 2MB per Rule Collection Group. They constitute a top level Azure resource, meaning that a dedicated template can deploy a single or multiple RCGs.

For smaller setups (up to 60 applications), each app can take its own Rule Collection Group. This will enable that each app team gets its own RCG, so that deployments impacting one team will not affect others (since the RCG is an independent resource in Azure).

For larger deployments, a rule collection group would represent a group of applications or Line of Business, and individual applications would get dedicated rule collections.

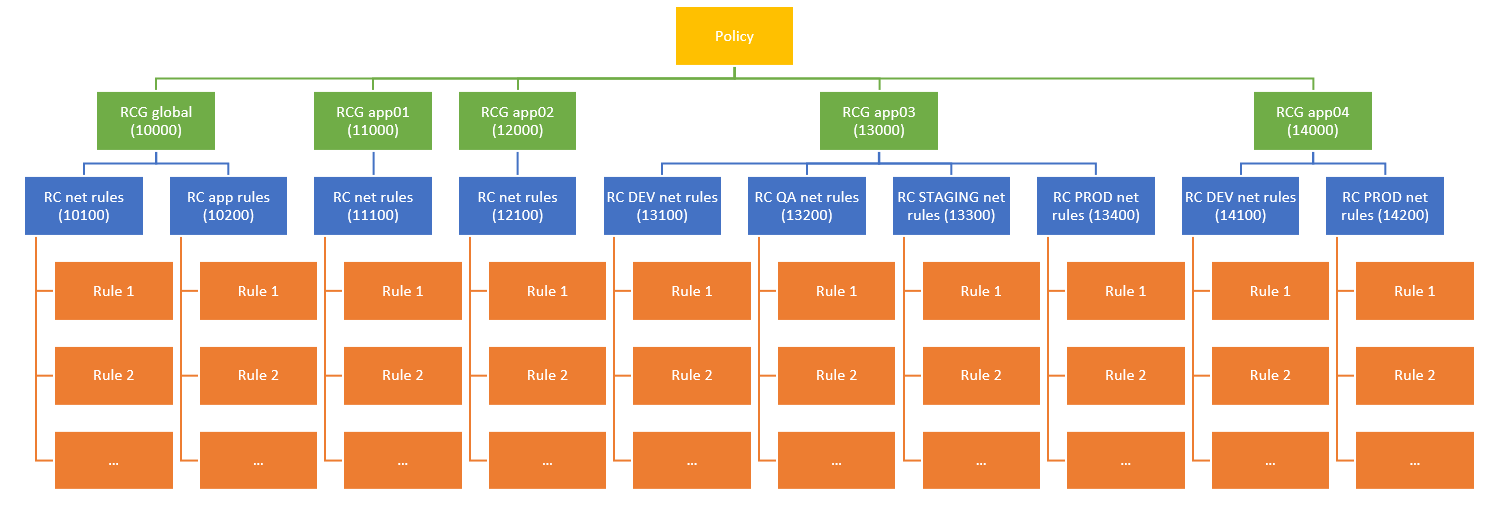

This repo implements the following hierarchy:

Some remarks:

- For each workload, a single rule collection group implements all environments and both network and application rules (a single rule collection cannot contain a combination of both)

- Some workloads will not have multiple environments, or some workloads will not require both network and application rules

- The rule collection group template for each workload will be stored in the workload's folder (for monorepo designs, in this example app01, app02 and app03) or in the workload's repo (for multirepo design, in this example app04).

- The model shown with the app03 app (rule collections for multiple apps/environments in separate files, that at deployment time are consolidated into a single template) can be followed by large organizations with hundreds of applications. Instead of having a RCG per app, these apps would be arranged in Lines of Business (LoB), and you would have an RCG per LoB. Inside of each RCG, each app environment would get its own rule collection, which would be merged into a single RCG bicep template for deployment.

Separate files for each administrative domain in your organization (like application owner groups) will help you to manage access to each item separately and configure different code owners.

Ideally you can separate files at resource boundaries. For example, you can have different files per Rule Collection Group (as in app01 and app02 or app03 in the examples in this repo), and giving access to each Rule Collection Group file to a different application team.

You might need to be more specific. For example, if with the previous scheme you ended up with more than 60 rule collection groups, that wouldn't be supported by Azure Firewall today (check Azure Limits). You could partition a single Azure resource (the rule collection group in this example) in multiple files, for example using the Azure bicep functions loadJsonContent and loadYamlContent. You can see an example of this setup in this repo, in the app03 folder, where app03's RCG loads up the the rule collections for each environment (test, qa, staging and prod) from a JSON file specific to each environment.

An alternative approach can be seen in the app03 ARM directory, where the script merge_rcg.py consolidates the different files into a single one.

In this repo we are using different files for each environment in the same app (see for example the app03 directory). The upside for this approach is that each environment is kept separately, and pipelines are only triggered when the corresponding file is modified. For example, changing the test environment file will not trigger a deployment in the production environment.

Additionally, from a networking perspective each environment has different IP addresses, so most of the configuration is going to be different as well.

The downside of this approach is the potential for configuration drift across environments. An alternative approach would be having some common files across the environments, and only modify the values unique to each of them (like IP addresses). While eliminating drift, this approach makes it much harder to try things out in a test environment without impacting production.

Two different approaches are presented in this repo, mostly derived from the differences between ARM and bicep (Terraform would be closer to bicep than to ARM here) regarding templates:

- Option 1 (recommended): single template. This the approach followed in the bicep directory. Whenever a change occurs in any of the files, the whole setup is deployed again. Since templates are idempotent, re-deploying the whole template shouldn't trigger any change on resources that do not have changes. One benefit of this approach is that the dependencies are taken care of inside the template, for example making sure that IP groups are created before the rule collection groups, so the workflow is kept relatively simple.

- Option 2: multiple templates. This is the approach followed in the ARM directory. While this approach gives a more granular control on the templates deployed, it moves the dependency logic from inside the template to the Github workflow. ARM doesn't have such an advanced file management mechanism like bicep or Terraform, so if you choose ARM this might be the only possible approach that allows to keep files separated.

Github actions can be used to validate that the different updates to each files don't break your rules. In this repo you can find some examples for validation actions:

- Shell-based:

- ipgroups_max verifies that the total number of IP Groups defined across the repository doesn't exceed a certain configurable maximum. This example sets the maximum to 80, below the current limit of Azure for 100. This action is using a shell script. Shell-based actions are composed of 4 files:

- action.yaml: inputs and outputs are defined.

- README.md: documentation on how to use the action (inputs/outputs)

- Dockerfile: this will be used by Github to create a container. It can be the same file for all your shell-based actions.

- entrypoint.sh: main logic of the action. It completes successfully if the checks are satisfactory, or with an error (

exit 1) if checks fail.

- action.yaml: inputs and outputs are defined.

- ipgroups_max verifies that the total number of IP Groups defined across the repository doesn't exceed a certain configurable maximum. This example sets the maximum to 80, below the current limit of Azure for 100. This action is using a shell script. Shell-based actions are composed of 4 files:

- Python-based:

- cidr_prefix_length: this Github action loads up JSON with a Python script to verify that the masks of CIDR prefixes used along the different files are not too broad. This python action includes an additional file:

- requirements.txt: Python modules that need to be installed. The Dockerfile contains the line

RUN pip3 install -r requirements.txtto process this file.

- requirements.txt: Python modules that need to be installed. The Dockerfile contains the line

- cidr_prefix_length_bicep very similar to the previous one, but in the case of bicep there is no JSON to load. Hence pycep-parser needs to be leveraged to transform bicep into JSON before analyzing it. See the Python script for more details.

- cidr_prefix_length: this Github action loads up JSON with a Python script to verify that the masks of CIDR prefixes used along the different files are not too broad. This python action includes an additional file:

It is important to define the file path and extensions that will trigger each check: you don't want to run ARM validation on bicep files or vice versa. In the workflows for ARM validation and bicep validation you find examples of this, for example to run the validation only when files in the ARM directory are changed:

on:

pull_request:

branches: [master]

paths:

- '**/ARM/*.json'Additionally to your custom checks, you can let Azure run your template in Validate deployment mode to be 100% sure that the template is correct (check Test your Bicep code by using GitHub Actions for a whole Azure Learn course on that topic).

The action to validate a template is very similar to the deployment, it only includes an additional line for the deploymentMode:

- uses: azure/arm-deploy@v1

name: Run preflight validation for shared infra

with:

resourceGroupName: ${{ secrets.AZURE_RG }}

template: ./shared/bicep/azfwpolicy.bicep

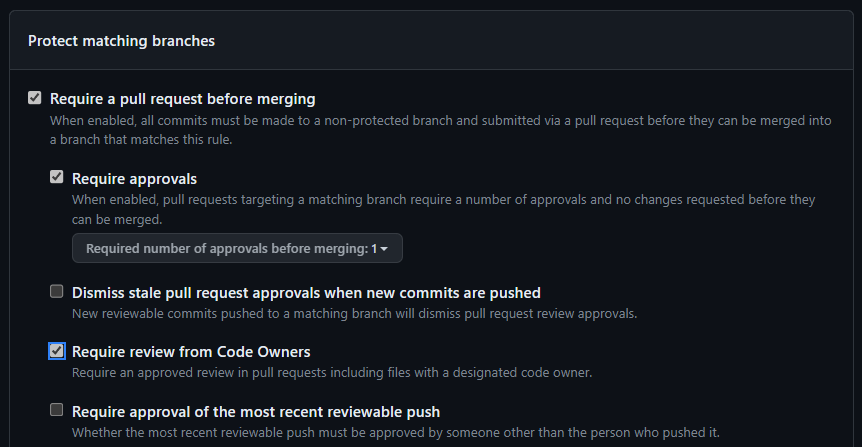

deploymentMode: ValidateIn order to ensure your checks are run before every push, you should protect the main/master branch, so that users always need to go through the Pull Request process, and not push straight into the branches. Different tests and checks will be performed in the PR, and a manual approval should be required before merging the PR.

When a PR doesn't satisfy all checks, the PR author will see the test results and will be able to correct them.

Once a Pull Request is merged, you can decide to deploy straight into the target environment, or whether to wait and deploy all changes at a fixed time, such as once a day. If you go for the continuous deployment option, your workflow should match both the main/master branch as well as the relevant files:

on:

push:

branches: [master]

paths:

- '**/ARM/*.json'If this filtering is not enough, you can use additional in-job filters to control actions, for example with the dorny/paths-filter Github action, as shown in the ARM workflow.

If going for scheduled deployments, you can leverage the on.schedule functionality in your Github actions. If you would like to deploy only if there were some commits in the period, you can use a variable containing the number of commits (24 hours in this example) to determine whether to run the deployment or not:

- name: Get number of commits

run: echo "NEW_COMMIT_COUNT=$(git log --oneline --since '24 hours ago' | wc -l)" >> $GITHUB_ENVAzure Firewall doesn't support concurrent operations, so you need to configure your workflows to never run concurrently. Github workflows offer the concurrency attribute for jobs to manage this, you can check how the ARM workflow and bicep workflow for Azure Firewall are configured to belong to the same concurrency group.

The same concept followed so far can be used as well in multi-repo approaches, where the infra code for other apps is located in remote repositories. In this sample, we checkout the whole remote repository in the workflow. For example, for an app04 stored in a remote repo segmentation-iac-app04, the bicep workflow checks out both the local and the remote repos:

# Checkout local repo

- name: Checkout local repo

uses: actions/checkout@main

# Checkout remote repo for app04 (the path is important, the bicep template expects to find it there)

- name: Checkout app04 repo

uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

repository: erjosito/segmentation-iac-app04

ref: master

path: './app04'The bicep template is configured to look for the module azfw-app04.bicep in the app04 folder, where the remote repo will be cloned.

Deploying Network Security Groups (NSGs) as code is an interesting exercise, since conversely to Azure Firewall policies, they are distributed in different subscriptions/landing zones.

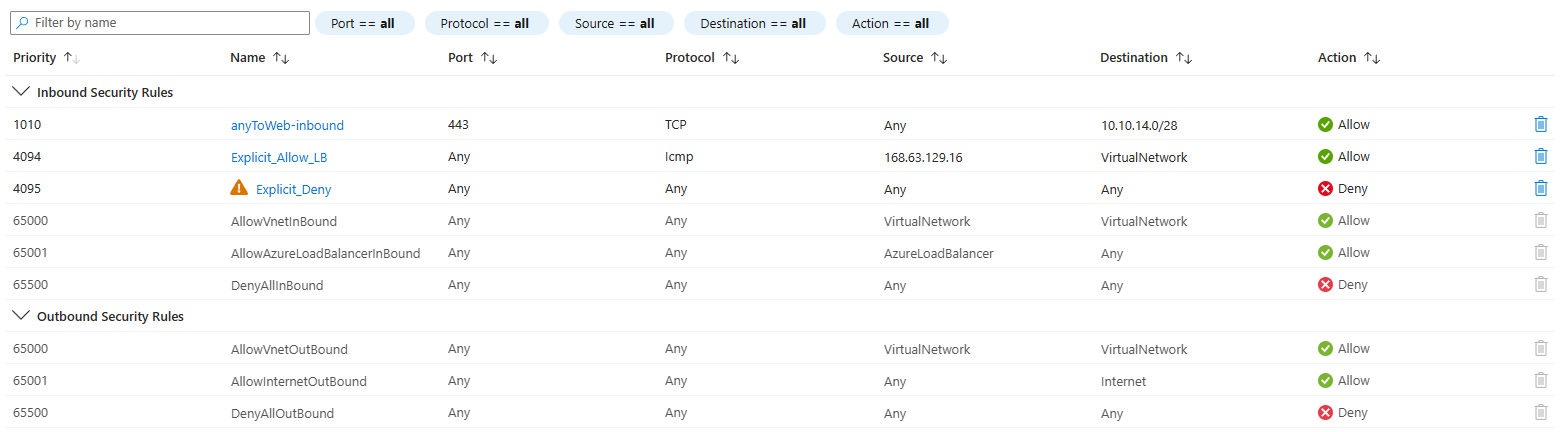

First of all, why shared rules? Even if application admins should be the owners of the code that controls the way their application components work, central IT will probably need to review the policies by app admins to make sure they are compliant with the organization's policy. This review exercise might result in the addition of some "common" or "shared" NSG rules:

- Blocking well-known insecure protocols, such as Telnet

- Blocking protocols not required by the organization, such as SMTP (in many cases)

- Including an explicit "deny" rule at the end of the application-related "allow" rules. The reason for this is that the default rules for Azure NSGs turn into very permissive "permit any to any" as soon as default routes (for

0.0.0.0/0) are installed in workload subnets. The reason is that theVirtualNetworkservice tag not only contains the VNet's prefix, as the name seems to imply, but everything for what the virtual machine has explicit routing for (0.0.0.0/0if there is an UDR for that).

You can manage NSGs in diffent ways:

- Azure Virtual Network Manager enables evaluating certain shared rules (called "admin NSG rules") before any other, which makes it ideal for dropping insecure or non-used protocols. However, it is not possible today deploying explicit denies after the "normal" NSG rules have been checked.

- You can use Azure Policy to deploy certain rules with specific parameters. See for example this policy to create an explicit deny rule with a low priority, and this policy to create another rule just before that allows the Azure Load Balancer as source IP (this one would be a great candidate to be inserted via AVNM though). While this approach is rock solid, a downside is that between the time of the deployment and the time when the Azure policy kicks in, there would be an interval where the NSG wouldn't be compliant, since it wold be missing these shared rules.

- Yet another approach (what we follow in this repo) is doing this addition in GitHub, before deploying, where the bicep templates defined by the app owners in their own folders (in monorepo) or repositories (in multirepo) are "enhanced" with an additional bicep modules coming from the shared folder.

For example, infra-app01.bicep contains the infrastructure specific to app01 (in this example only an NSG). In the NSG module nsg-app01.bicep you can see the module sharedInboundRules, which gets some rules from the shared folder of the repo.

Some administrators prefer updating simplified versions of the code, instead of managing the bicep, ARM or Terraform files natively. Another usage of the bicep function loadJsonContent is allowing this way of work, which has been implemented in the repo for app02.

In this example, admins can work on a CSV version of the rules, which upon commit will be transformed into JSON by nsg_csv_to_json.py, and then imported into the NSG template in nsg-app02.bicep using the loadJsonContent function.

Here the relevant code of the deploy workflow deploy_app02_infra.yml:

# Expand CSV file with NSG rules to JSON

- name: Expand CSV file with NSG rules to JSON

run: |

python3 ./scripts/nsg_csv_to_json.py --csv-file ./app02/bicep/nsg-rules-app02.csv --output-file ./app02/bicep/nsg-rules-app02.json --verbose

# Log into Azure

- uses: azure/login@v1

with:

creds: ${{ secrets.AZURE_CREDENTIALS }}

# Deploy bicep template

- name: Deploy bicep template for global policy

uses: azure/arm-deploy@v1

with:

subscriptionId: ${{ secrets.AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION }}

resourceGroupName: ${{ secrets.AZURE_RG }}

template: ./app02/bicep/infra-app02.bicep

parameters: prefix=app02Looking at our application app04 with a separate repository (segmentation-iac-app04), this application will be deployed in a different subscription, with a different Virtual Network, and of course different NSGs (making up a dedicated landing zone).

The Azure credentials, including the subscription ID and resource group for app04 are stored in the secrets of that repo. NSGs should be deployed in the same subscription as the VNet, hence it is logical that the deployment workflow runs in the app04's repo (the repo with the shared resources shouldn't need the credentials to the workload's subscription). And yet, the shared repo might contain some required information.

In this example, the shared repo contains some common NSG rules that are to be inserted in every NSG for all workloads. Consequently, the workflow in segmentation-iac-app04 checks out the shared repo as well, and the NSG bicep template contains a module to be found in the folder where the shared repo is cloned.

After running the template, you can see that the NSG is created with the rules contained in the local repo, and the shared rules from the shared one:

This repo has demonstrated multiple concepts, such as:

- Sharing info across repositories for centralized and distributed resources

- Custom checks using shell and Python scripts

- File management for effective validation and deployment of code

- Azure Firewall structure for rule management across teams

- Implementation of shared NSG rules across the organization