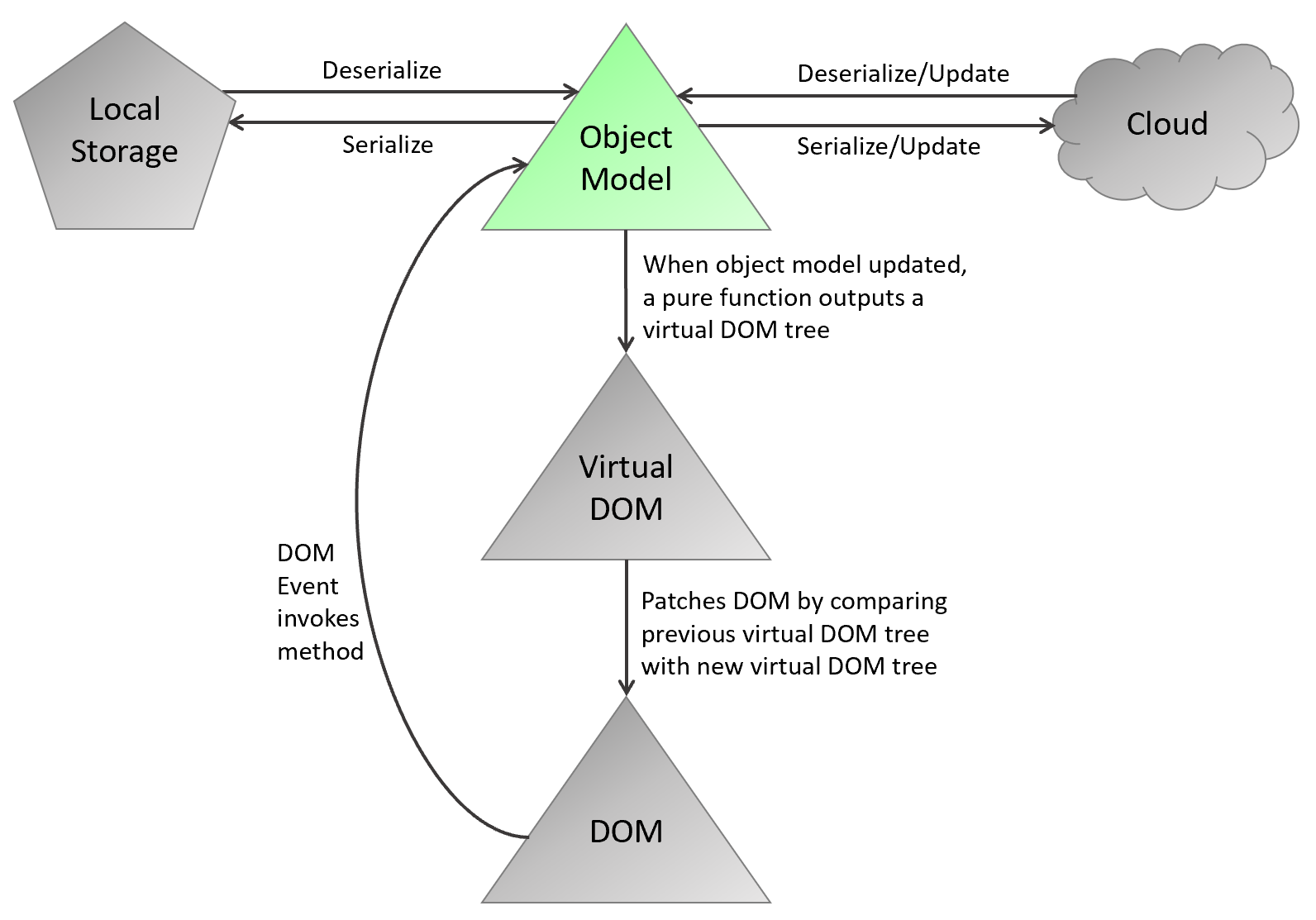

Solenya is the web framework for you if you like conceptual simplicity. The heart of a solenya application is your object model. The solenya API lets you easily translate your object model to the DOM, the cloud, and local storage.

Here's the motivation for Solenya. But if you just want to learn it, you can skip that and just keep reading.

- Solenya website: https://www.solenya.org

Open a github issue, or email codingbenjamin@gmail.com.

Here's a counter component in solenya:

export class Counter extends Component

{

count = 0

view () {

return div (

button ({ onclick: () => this.add (1) }, "+"),

this.count

)

}

add (x: number) {

this.update(() => this.count += x)

}

}In solenya, application state lives in your components — in this case count.

Components can optionally implement a view method, which is a pure non side effecting function of the component's state. Views are rendered with a virtual DOM, such that the real DOM is efficiently patched with only the changes since the last update.

Components update their state exclusively via the their update method, which will automatically refresh the view. It really is that simple. In fact, simplicity is the defining characteristic of solenya.

Solenya is small: see and understand the source code for yourself. Its power comes from its simplicity, composability, and integration with other great libraries.

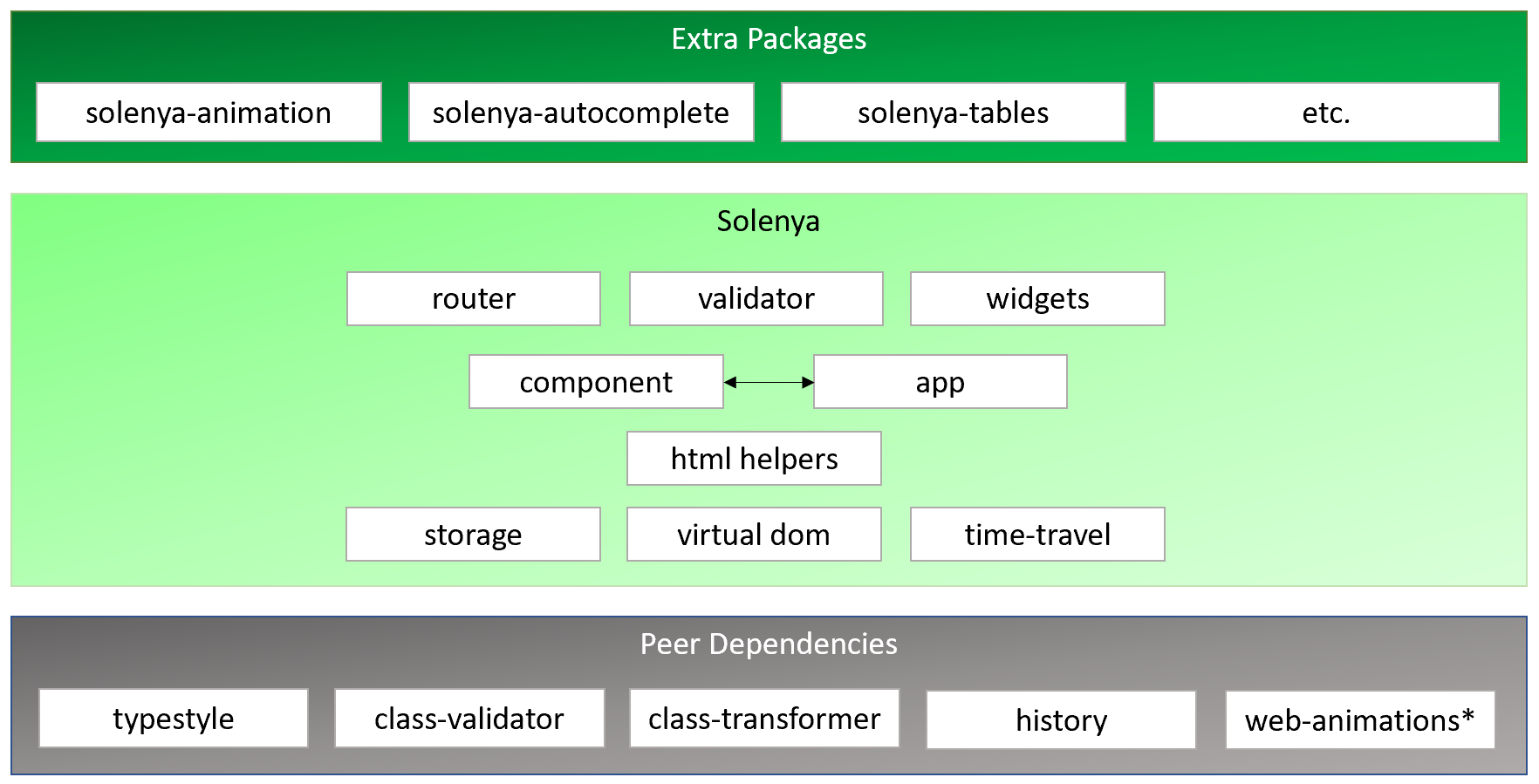

In the following diagram, higher layers have a dependency on lower layers.

The 3rd party libraries Solenya has a dependency on are:

typestyleis used to express css styles in typescriptclass-validatoris used by the solenya validatorclass-tranformeris used to serialize solenya componentshistoryis used by the solenya router- *web-animations (polyfill:

web-animations-js) is used by the solenya-animation package, though you can also use any other 3rd party animation library

All dependencies between npm packages are peer dependencies.

Solenya works with all major browsers, including IE11 if you install the es6-shim.

npm install solenya

Depending on your npm setup, you may have to explicitly install the peer dependencies listed above.

- Solenya

- Samples

- Contact

- First Code Sample

- Dependencies

- Installation

- State, View and Updates

- Composition

- Component Initialization

- Updates

- HTML Helpers

- Style

- Forms

- 'this' Rules

- Routing

- Child-To-Parent Communication

- Interacting with the DOM

- App

- Time Travel

- Serialization

- Hot Module Reloading

- Async

- Data Properties

- Merging Attributes

- Motivation

- API Reference

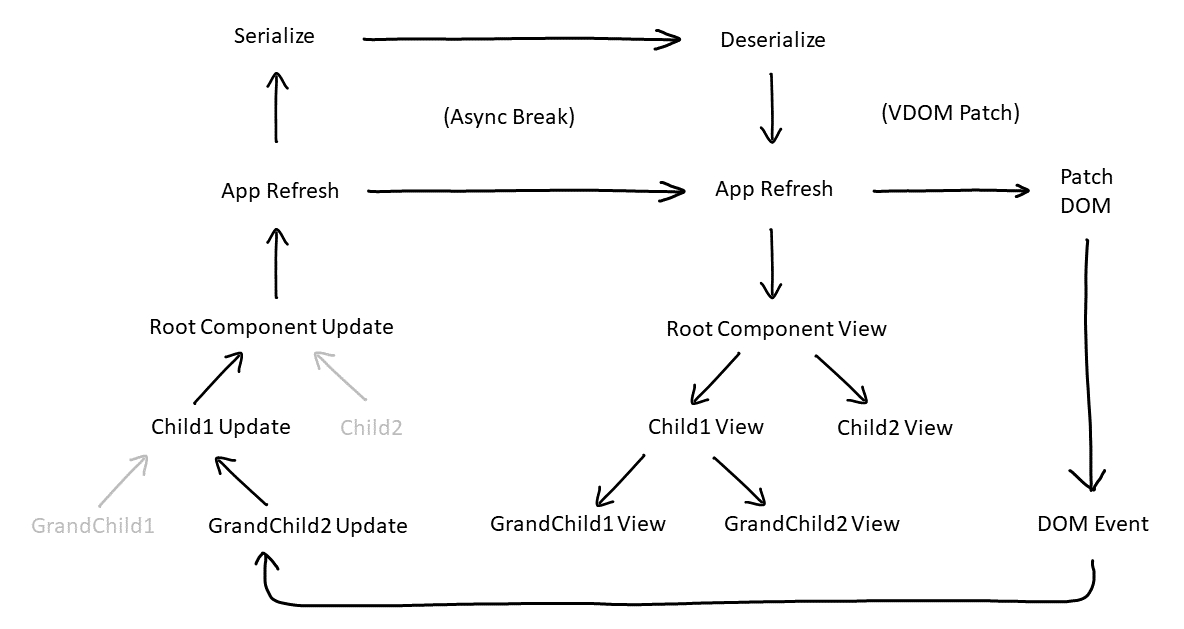

A solenya app outputs a virtual DOM node as a pure function of its state. On each update, the previous root virtual DOM node is compared with the new one, and the actual DOM is efficiently patched with the change. DOM events can trigger updates, which result in a view refresh, forming a cyclic relationship between the state and the view.

Components help you factor your app into reusable parts, or parts with separate concerns. An app has a reference to your root component.

Components are designed to be serializable. When autosave or time travel is on, your component tree is serialized on each update. This provides a unified approach to time travel debugging, hot module reloading, transactions, and undo/redo. Serialization is covered in more detail in the serialization section.

This flow diagram represents updating a GrandChild2 component. In this case, we have a very simple application, where the view tree mirrors the component tree. As an application gets larger, the view tree will typically only represent a subset of the component tree. For example, in an application with wizard steps, the component tree would probably have every wizard step, while the view tree would only have the current wizard step.

Composition is straightforward with solenya, allowing you to factor your application into a tree of smaller components:

export class TwinCounters extends Component

{

counter1 = new Counter ()

counter2 = new Counter ()

view () {

return div (

this.counter1.view (),

this.counter2.view ()

)

}

}Components must have parameterless constructors, though they may include optional arguments. This small design restriction enables class-transformer's deserializer to work.

Child components should be created in the constructors, field initialisers, and updates of their parents.

You can specific arrays of components, recursive components, or even arrays of recursive components. Here's from one of the samples. The type annotation is required to allow deserialization to work for arrays, as typescript erases the type of the property after compilation.

export class Tree extends Component

{

@Type (() => Tree) trees: Tree[] = []

...

}You component's life begins with a constructor call. As described later, the deserializer will still call your constructor, but then set the object's properties. That's why your constructor's arguments must be optional.

When your app is first created or deserialized, and after every update, a depth-first traversal occurs, where attached is called on every component not already attached:

attached (deserialised: boolean) {

...

}On the traversal, child components are identified by being properties or property array elements of the parent. As such each child will get attached, and have its parent and app properties set (except the root component which obviously has an undefined parent). This enables updates to a child to bubble up to the root component.

After app startup or deserialization, all state transitions must occur within an update.

An update is straightforward:

add (x: number) {

this.update(() => this.count += x)

}You pass update a void function that performs a state transition.

At the end of an update, the root component's view method is called. Updates are synchronous, but views are refreshed asynchronously.

Nested updates are regarded as a single update. The view will at most be called once for an update.

In more advanced scenarios you can capture updates, as explained later in the child-to-parent-communication section.

Views are pure functions of state. Solenya uses a virtual DOM (forked from Ultradom) to efficiently update the actual DOM.

You can add as may optional parameters as you want to your child component View methods. This makes it easy for parents to customize their children without their children needing extra state:

view () {

return div (

this.child1.view (...),

this.child2.view (...)

)

}view methods return the type VElement. However, your component might be faceless, having no view implementation, or might have several methods returning different VElement objects. This is because solenya components are state-centric, not view-centric.

To write a reusable view, your first approach should be to merely write a function that returns a VElement. Only use child components when you need to encapsulate state.

The HTML helpers take a spread of attribute objects, elements, and primitive values. Solenya has been designed to work well with Typescript, so your IDE can provide statement completion. In conjunction with typestyle, as we'll see later, we get a deep, clean static typing experience.

Attribute objects go first. Some examples:

div () // empty

div ("hello") // primitive value

div ({id: 1}) // attribute

div ({id: 1, class: "foo"}) // multiple attributes

div ({id: 1}, "hello") // attribute followed by element

div (div ()) // nested elements

div ({id: 1}, "hello", div("goodbye")) // combinationMultiple attribute objects are merged. Merging attributes is really useful when writing functions allowing the caller to merge their own attributes in with yours. The following are equivalent:

div ({id: 1}, {class:"foo"})

div ({id: 1, class:"foo"}) All the HTML element helper functions such as div and span, call through to the h function. The h function merges multiple attribute objects using the mergeAttrs method, which you can also directly call yourself.

Event handlers are specified as simply a name followed by the handler:

button (

{ onclick: () => this.add (1) }, "+"

)

To aid porting, an online HTML-to-Code converter is available on both solenya.org and stackblitz.

While you can use ordinary css or scss files with solenya, solenya has first class support for typestyle, that lets you write css in typescript.

The key advantages are:

- Typescript is far more powerful than any stylesheet language - it's a better way to organize and abstract your styles.

- It eliminates the seam between your view functions and styles - easily pass in variables to dynamically create styles.

- You can colocate your code with your styles, or provide exactly the appropriate level of coupling to maximise maintainability.

Here's what it looks like:

div ({style: {color:'green' }}, 'solenya')Solenya will call typestyle's style function on the object you provide. It's as if you called:

div ({class: style ({color:'green'})}, 'solenya')If you need to reuse a style, then don't inline the style: declare it as a variable and refer to it in your class attribute. You can factor it just as you please.

Typestyle will dynamically create a small unique class name, and add css to the top of your page. So the following:

div ({style: {color: 'green'} },

"solenya"

)Which will generate something like:

<div class="fdwf33">

solenya

</div>With the following css:

fdwf33 {

style: green;

}Solenya automatically merges css values. The following are equivalent:

div ({class: "big"}, {class: "happy"})

div ({class: "big happy"})You may also use ordinary style strings rather than objects, which bypasses the typestyle library.

Since style objects are actually converted into classes, they may not override other styles in other classes that apply to that element. If this is a issue either add the !important modifier to the style, or revert to a string style. You should however discover that with typestyle you have less need to use the !important modifier in the first place as you can better abstract your styles.

To make writing forms easier, solenya provides some widget functions for common inputs. You can easily build your own ones by examining the widgets source code.

inputText: text inputinputNumber: numeric inputinputValue: restricted input - use to make custom inputs such aspercentInputorcurrencyInputinputTextArea: text area inputinputRange: numeric range inputselector: select inputradioGroup: group of labelled radio buttonscheckbox: labelled checkbox

The input functions are css agnostic - you can precisely control an input's attributes and nested element attributes. This enables you to write your own wrapper functions around these functions to target a particular css framework with your particular style. You then only need change the internals of your wrapper functions for all your forms code across your entire application to target completely different css.

In this example, we write a BMI component with two sliders:

export class BMI extends Component

{

height = 180

weight = 80

calc () {

return this.weight / (this.height * this.height / 10000)

}

view () : VElement {

return div (

div (

"height",

inputRange ({target: this, prop: () => this.height, attrs: { min: 100, max: 250, step: 1 } }),

this.height

),

div (

"weight",

inputRange ({target: this, prop: () => this.weight, attrs: { min: 100, max: 250, step: 1 } })

this.weight

),

div ("bmi: " + this.calc())

)

}

}All inputs are databound, and all take a single parameter. That parameter always inherits from the base class InputProps<T>:

export interface InputProps<T> { // T is the data type to bind to (e.g. a number)

target: Component, // component to bind to

prop: PropertyRef<T>, // target property, e.g. () => this.weight

attrs?: HAttributes // the attributes for the input

}The target and prop properties reference a component's property, enabling the input to be databound to that property. The PropertyRef<T> type can either take a function that refers to a property, such as () => this.weight or a ordinary string, e.g. weight. The former (statically typed) should be used when you know the property at compile time, and the latter (dynamically typed) should be used when you only know the property at runtime.

Minimially, all inputs will have an optional attrs type. More complex input types have many other properties, including nested attributes, which can be merged together as explained in the merging section.

In the above example, there's clearly boilerplate. In the next section, you'll notice you can easily write your own inputUnit higher-level function that generalizes the concept of an input with a label and validation.

The solenya library comes with a validator.

The solenya validator builds on the excellent class-validator library to validate with javascript decorators. Here's an example of validating some properties on a component:

export class ValidationSample extends MyForm implements IValidated

{

@transient validator: Validator = new Validator (this)

@Label("Your User Name") @MinLength(3) @MaxLength(10) @IsNotEmpty() username?: string

@Min(0) @Max(10) rating? number

@IsNumber() bonus? number

ok() {

this.validator.validateThenUpdate()

}

updated (payload: any) {

if (this.validator.wasValidated)

this.validator.validateThenUpdate (payload)

}

view () : VElement {

return div (

inputUnit (this, () => this.username, props => inputText (props)),

inputUnit (this, () => this.rating, props => inputNumber (props),

inputUnit (this, () => this.bonus, props => inputCurrency (props)),

div (

myButton ({ onclick: () => this.ok() }, "ok")

)

)

}

}By decorating class properties, you can express constraints, as well as custom labels to be used for display and validation.

When you're ready to validate (in this case because the user clicked 'ok'), you call the validator's validateThenUpdate method. This compares the component's properties to the constraints on those properties. When complete, the validationErrors property on the validator will contain an element for each property with constraint violations.

We use the component's update method to keep validated after we've first validated, to give the user continuous feedback. We can also manually flip wasValidated back to false.

Validation works recursively for child components that also implement IValidated.

Validation can be asynchronous, since you'll sometimes need to call a service to determine validity.

class ValidationSample extends Component implements IValidated

{

async customValidationErrors() {

...

}

}The return type is Promise<ValidationError[]>, where ValidationError is a a type from the class-validator package.

The this variable's binding is not as straightforward as in object oriented languages like C# and Java. There's a great article about this here.

Within solenya components, follow the pattern you see in this documentation, which has two rules:

Always wrap a method that's used as a callback in a closure, otherwise this might be lost before it's bound.

// RIGHT

methodUsingYourCallback (e => this.updateProperty (e))

// WRONG

methodUsingYourCallback (this.updateProperty)Use ordinary class methods, not function members when calling update. Otherwise cloning — which solenya relies on for time travel — fails, since the cloned function will refer to the old object's this.

// RIGHT

add () {

return this.update (...

// WRONG

add = () =>

this.update (...The solenya library comes with a composable router.

The samples use routing in two places. First, each sample has it's own route. Second, we use a router so that each tab in the "tabSample" has a nested route. So here's the possible routes:

/counter

/bmi

/tabSample/apple

/tabSample/banana

/tabSample/cantaloupe

Let's start with the outer router first.

export class Samples extends Component implements IRouted

{

@transient router:Router = new Router (this)

@transient routeName = ""

counter = new Counter ()

bmi = new BMI ()

tabSample = new TabSample ()

...

attached()

{

for (var k of this.childrenKeys()) {

this[k].router = new Router(this[k])

this[k].routeName = k

}

...

}

}

A component can be routed by implementing IRouted. A routed component defines a routeName property that corresponds to a name in a path.

So for the path /tabSample/banana, there's a component with the tabSample routeName, which has a child component with the banana routeName. The root component, Samples has an empty string for its routeName.

A current route is represented with a component route's currentChildName value. So the currentChildName of the Samples component's router is tabSamples, and the curentChildName of the TabSample component's router is banana. Finally, the currentChildName of the banana component's router is simply ``, since it's a leaf node, i.e. itself has no children.

By default, the mapping from parent and child name to child component occurs by scanning the parent for children and returning one that has a routeName that (case insensitively) matches the name provided. For complete control, you could implement the childRoute method to customize that default behaviour.

You can call a component router's navigate method, specifying the child path to go to. All routes are expressed relatively, not absolutely. In the examples below, we navigate to banana:

// when navigating from 'banana':

this.router.navigate ('')

// when navigating from 'tabSample':

this.router.navigate ('banana')

// when navigating from 'apple', via the parent

this.router.parent.navigate ('banana')

// when navigating from 'apple', via the root

this.router.root.navigate ('tabSample/banana')

Your first navigation typically occurs in the attached method of your root component. For example:

export class Samples extends Component implements IRouted {

attached() {

...

this.router.navigate (location.pathname)

}

...

}

The initial call to navigate on your root router is special in terms of navigation events:

- History tracking begins

- This means from then on, actions such as the back and forward button on the browser will trigger navigation events.

- (The router internally uses the

historyapi to update the browser history and to respond to browser navigation events.)

- Navigation callbacks always run

- The

beforeNavigateandnavigatedcallbacks on your component, if present, will be called even if the current url is identical to the url navigated to. - This is because before the initial navigation, it shouldn't be assumed that the application state reflects the current url.

- The

We can implement the navigated method to detect when a component is routed. We do this in the Relativity sample, where we have a continuous animation that we want to trigger when the component is routed:

export class Relativity extends Component {

navigated() {

...

}

}navigated will be called for each component in the path.

We intercept navigate by implementing beforeNavigate. It's important to be able to intercept navigation for several reasons:

- Prevention: We don't want the user to leave the current form until it's validated, or perhaps we want to redirect the user to another route

- Preparation: We need to fetch data, perhaps asynchronously, before we can complete the navigation.

- Redirection: We want to redirect the user by canceling the current navigation and navigating to a new path.

In the TabGroup component, we use beforeNavigate for two purposes. First, we want to redirect to the first nested tab if no tab is selected. Second, we want to animate the tab left or right, depending on whether the new tab's index is less than or greater than its previous index.

export abstract class TabGroup extends Component implements IRouted

{

@transient router: Router = new Router (this)

@transient routeName!: string

attached() {

for (var k of this.childrenKeys()) {

this[k].router = new Router (this[k])

this[k].routeName = k

}

}

async beforeNavigate (childPath: string) {

const kids = this.childrenKeys()

if (childPath == '') {

this.router.navigate (this.router.currentChildComponent ? this.router.currentChildName : kids[0])

return false

}

this.slideForward = kids.indexOf (childPath) > kids.indexOf (this.router.currentChildName)

return true

}We return false when we want to cancel a navigation, and true when we're happy that the navigation goes ahead. The beforeNavigate method works very well in tandum with validation, that we discussed earlier. If your current state isn't valid, it's very common to prevent the navigation occuring by returning false.

We can now use TabGroup as follows:

export class TabSample extends TabGroup

{

apple = new MyTabContent ("Apples are delicious")

banana = new MyTabContent ("But bananas are ok")

cantaloupe = new MyTabContent ("Cantaloupe that's what I'm talking about.")

}For convenience, router has a function for generating navigation links. These look like ordinary url links, but they use the onclick event to ensure the router's navigation method is called, rather than jumping to a new page:

navigateLink (path: string, ...content: HValue[])Use composition to manage complexity: as your application grows, parent components compose children into larger units of functionality. However, sometimes communication has to go in the reverse direction: from child to parent. This is done in one of three ways:

- Callbacks

- Parent Interface

- Update Path

With all of these approaches, the single-source-of-truth is always maintained. Avoid copying state.

With this approach, the parent passes a callback to the child:

class ParentComponent extends Component {

@Type (() => ChildComponent) child: ChildComponent

view () {

return (

...

child.view (() => this.updateSomeValue())

...

)

}

}

class ChildComponent extends Component {

...

view (updateSomeValue?: () => void) : VElement {

...

}

}It's worth repeating that you should only use a child component if the child component has its own state. If not, save yourself some typing and replace your child component with a function that returns a VElement.

In this sample, we use the callback pattern, both when factoring out a child component (taskItem), and factoring out a function that returns a view (linkListView):

Note that a small design restriction is that the arguments to view must be optional to support the parameterless super class view.

With this pattern:

- The parent component implements an interface for exposing only the state your child needs to see

- The child component has a method that returns this.parent cast to the parent interface

So the code structure is as follows:

interface IParent {

someMethod() : SomeType

}

class ParentComponent extends Component implements IParent {

someMethod() { return ... }

...

}

class ChildComponent extends Component {

iparent() { return <IParent>this.parent }

...

}The purpose of the interface is to reduce the surface area of the parent that the child can see, so that you can more easily reason about your code.

You may also use the Component's root(), or branch() API (explained in the API section further below) to target a specific ancestor, rather than the immediate parent.

It's almost always a bad idea to access a sibling component. Instead, the child should access the parent, and the parent should interact with the other child.

We highly recommend you install the circular-dependency-plugin package, and run it as part of your build process. Keep your cyclomatic complexity low!

All state changes to Component trigger its updated method:

updated (payload: any) {

...

}The updated method will be subsequently called on each parent through the root. This allows a parent to respond tp updates made by its children, without having to handle specific callbacks.

The payload property contains any data associated with the update. The source property will be set to component that update was called on, which is occasionally useful.

You may call Component.onRefreshed to queue a callback to perform DOM side effects after the next refresh. You typically do so in the view method:

view() {

this.onRefreshed (() => { ... }) // called after DOM is updated

return div (...)

}You may however, need deeper control side-effecting the DOM.

For the most part, views are pure functions of state. However, DOM elements can have additional state, such as inputs that have focus and selections. Furthermore, animations, at a low level, need to interact with the DOM bypassing the virtual DOM. This is for both performance reasons (as you don't want to invoke the GC), as well as keeping your application state logic separated from your animation state. For example, if you delete an item from a list, it's a simplifying assumption for your application state to consider that item gone, but you'll want that item to live a little longer in the real DOM to gracefully exit.

To interact with the DOM directly, you provide lifecycle callbacks on your virtual DOM elements. The lifecycle callbacks should be familiar to anyone familar with a virtual dom:

export interface VLifecycle

{

onAttached? (el: Element, attrs: VAttributes) : void

onBeforeUpdate? (el: Element, attrs: VAttributes) : void

onUpdated? (el: Element, attrs: VAttributes) : void

onBeforeRemove? (el: Element) : Promise<void>

onRemoved? (el: Element) : void

}

onAttached is called when an element is attached to the DOM.

onUpdate is called whenever an element is updated. Use it to perform any final updates to the DOM. The onBeforeUpdate lets you take any preliminary actions before the element changes.

onRemoved is called when an element is removed from the DOM.onBeforeRemove allows you take any preliminary actions - which may be asynchronous - before an element is removed.

Here's how you might plug in some focusing logic when an element is added to the DOM:

div ({

onAttached: (el, attrs) => handleFocus (el...)

...When the patcher adds an element to the DOM corresponding to your virtual div element, it invokes the onAttached callback.

Lifecycle callbacks automatically compose. So both onAttached functions will be called here, in the order of appearance:

div (

{

onAttached: (el, attrs) => handleFocus (el...)

},

{

onAttached: (el, attrs) => handleSelection (el...)

}

...

}After each update, the virtual DOM is patched. The patcher compares the current virtual DOM tree to the previous one, and modifies the real DOM accordingly. However, the patching algorithm can't know your intent, and so occassionally does the wrong thing. It may try to reuse an element that you definitely want to replace, or it may try to replace a list of child elements that you merely wanted to reorder. To better determine the creation and destruction of DOM nodes, provide keys for your virtual DOM nodes. For example:

div ({key: wizardPage})If the key changes, the patcher now knows to definitely recreate that DOM element. This means even if your next wizard page happened to have an input that could have been updated, that instead it will be replaced, predictably resetting DOM state like focus and selections, and invoking any animations that should occur on element creation.

Let's combine the concepts in the previous sections to shuffle an array, where each element gracefully moves to its new position each time the array is updated. We can use lodash's shuffle function to perform the shuffle, and our own transitionChildren function to perform the animation. We'll need to make sure each item in the array has a unique key, so that the patcher knows to reuse each child element.

export class AnimateListExample extends Component

{

@transient items = range (1, 20)

view () {

return div(

myButton ({ onclick: () => this.shuffle () }, "shuffle"),

ul (transitionChildren(), this.items.map (n => li ({ key: n }, n)))

)

}

shuffle() {

this.update (() => this.items = shuffle (this.items))

}

}We can implement transitionChildren using the FLIP technique:

export function transitionChildren () : VLifecycle

{

return {

onBeforeUpdate (el) {

let els = el["state_transitionChildren"] = Array.from(el.childNodes).map(c => (c as HTMLElement))

els.forEach (c => measure(c))

},

onUpdated (el) {

let els = el["state_transitionChildren"] as HTMLElement[]

els.forEach (c => flip (c))

}

}

}By design, these lifecycle events are not present on solenya components. Solenya components manage application state, only affecting DOM state via its view method, and the intentionally ungranular onRefreshed method. This lets you separate the very different lifecycles of application state and DOM state, making your code easier to maintain.

While there's always pragmatic exceptions, the principles of solenya state are:

- Application state belongs on components.

- DOM state belongs on DOM elements.

- No state belongs on virtual DOM elements.

To start Solenya, pass the constructor of your top level component into your App instance, with a string defining the id of the element where you app will be hosted. For example:

import { App } from 'solenya'

var app = new App (Counter, "app")You can also construct the application from an explicit instance. This can be useful when you've deserialized the component from somewhere else, such as a server.

var app = new App (Counter, "app", {rootComponent: counterFromTheWeb })Make sure you've read the serialization section to ensure your component deserializes correctly.

Maintaining state history is useful when you want transactions, undo/redo, and time travel debugging.

You can turn time travel on and off on App as follows:

app.timeTravelOn = true|falseNow all updates will be recorded.

You can now navigate as follows:

time.start() // goto start state

time.end() // goto end state

time.next() // goto next state

time.prev() // goto prev state

time.goto(4) // goto nth stateYou can also use a predicate to seek a particular state:

time.seek(state => state.counter.count == 7)When time travel is on, solenya serializes the component tree on each update. It's efficient and mostly transparent, but make sure to read the serialization section.

Sometimes you want to serialize your application to local storage.

To save our application with each update, we set the app autosave property on the app's storage object to true:

app.storage.autosave = trueThis will save your serialized component tree in local storage with the container id you specified (e.g "app").

To turn autosave off and clear your application state from local storage:

app.storage.autosave = false

app.storage.clear()It's critical to be aware that Typescript transpiles away property types (unlike in C# or Java). The @Type decorator of the class-transformer serialization package can be used to ensure nested components deserialize with the correct types:

export class Composition extends Component

{

@Type (() => Counter) counter1: Counter

@Type (() => Counter) counter2: Counter

}As a shortcut, you can also call initDecorators in your constructor. This will automatically add @Type decorators by scanning for non-undefined instance properties (and do so recursively):

export class Composition extends Component

{

counter1 = new Counter ()

counter2 = new Counter ()

constructor() {

super()

this.initDecorators()

}

}You must always apply the @Type annotation to arrays of components (do not include the []):

export class ItemList extends Component

{

@Type (() => Item) myList: Item[] = []

}Avoid circular references unless you absolutely need them. Firstly, the serializer doesn't handle them, and secondly, it increases your cyclomatic complexity which is why some languages like F# deliberately force you to minimize them. However, occassionaly you'll need them. To do so:

- override component's

attachedmethod to set the circular references there - exclude the circular references from being serialized with the

@transientdecorator

As a general rule, don't gratuitously use component state, and instead try to use pure functions where you can. In particular, avoid storing UI styles in component state - instead pass styles from a parent view down to child views. If you must store a UI style in a component, you'll probably want to decorate it with @transient to avoid serialization.

Serialization, deserialization, and local storage are surpisingly fast. However, efficiency is still important. Avoid properties with large immutable objects, and instead indirectly reference them with a key. For example, instead of directly storing a localisation table of French data on your component, you'd merely store the string "fr", and return the localisation table based on that key. Minimize the state on your components to that which you need to respond to user actions; keep it as close to a state machine as possible.

When your application state is serialized, an ordinary page refresh will run your modified code with your previous state. We can automatically trigger a page refresh by listening to server code changes:

module.hot.accept('../app/samples', () => {

var latest = require ('../app/samples')

window["app"] = new App (latest.Samples.prototype.constructor, "app", {isVdomRendered: true})

})

The isVdomRendered parameter tells the new app instance that there's already a rendered tree, so do a patch rather than create the DOM from scratch.

Solenya's update path is synchronous, so you perform aynchronous activites outside of update. Suppose a button invokes your submit event handler that calls a web service. That could be defined as follows:

async submit () {

var result = await fetch(url)

if (result.ok) {

this.update (() => ...)

}

}Notice that the update occurs after the asynchronous operation has completed.

Both the Validator and Router, covered in their own sections, are designed to operate asynchronously.

The samples demonstrate calling github's search, with debouncing.

It's common for your components to have a mixture of properties representing your domain model, such as firstName or phone, and properties representing infrastructure, such as validator or router. You can programmatically get just the domain properties by calling a component's dataKeys property, which ignores all properties decorated with @transient:

class Animal extends Component

{

@transient router?: Router = undefined

@transient validator?: Validator = undefined

species = ""

caloriesPerDay = NaN

view() {

return div (this.dataKeys().join (",")) // species,caloriesPerDay

}

}You can think of dataKeys like Object.getKeys, but for data.

The Component class's properties such as app and parent are decorated as @transient.

@transient will automatically also decorate your property with class-transformers's @Exclude() decorator, so that such properties don't partake in serialization.

It's common to want display the name of a data property to the user. The @Label decorator can be used exactly for this purpose:

class Animal extends Component

{

@Label("Species") name = "Elephant"

caloriesPerDay = 70000

// prints:

// Species: Elephant

// Calories Per Day: 70000

view() {

return div (

this.dataKeys().map (k =>

div (printProp (this, k))

)

}

}

const printProp<T> (obj: any, prop: PropertyRef<T>) =>

getFriendlyName (obj, prop) + ": " + getPropertyValue (obj, prop))getFriendlyName checks to see if there's a @Label, and if not, falls back to calling humanizeIdentifier on the property name. This means that by default, your users will see Calories Per Day instead of caloriesPerDay or calories-per-day.

The validation sample referred to earlier shows how to hook up validation to use @Label.

Solenya provides merging functions to make it easier to write reusable and chainable helper functions.

By default, calling an element function prefixed with multiple attribute objects merges those attributes. For example:

div ({x:1}, {y:2}) // this

div ({x:1, y:2}) // becomes thisYou can also use the mergeAttrs and mergeNestedAttrs helper functions to explicitly merge attributes. mergeNestedAttrs takes several objects, scans for properties on those objects whose name ends with attrs, and then calls through to mergeAttrs to merge those attributes and styles.

Let's suppose we create a resuable myInputText that customises inputText as follows:

export const myInputText = (props: InputEditorProps<string|undefined>) =>

inputText (mergeNestedAttrs (props, { attrs: {

type: "text",

class: "form-control"

}}))Calling:

myInputText ({target: this, prop: () => this.email, attrs: {

type: "email",

class: "special"

}})Outputs:

<input

type="email"

class="special form-control"

...

/>Occasionally you'll get a merge collision. Solenya favors the attribute that comes first. This is the opposite behaviour of the spread operator, and for good reason: as a callee writing a reusable function you want the caller's attribute object to come first, take precedence, and drive type inference.

Simplicity is a deeply important quality of code, and as such, has become a superlative in programming. Superlatives work on us because we naturally want to believe great things about ourselves: my code is simple. But of course, your code is complicated, and now simplicity is not objective, but subjective. This subjectivity is exacerbated by the restricted environment of the coding islands we live on. Of course code can be simple when it ignores critical concerns of a larger world.

But to abandon an objective meaning of 'simple' is to abandon being a good programmer, or to think so provincially that such meanings are never contemplated. Because the side-effects of complexity are costly code bases defended by programmers who's actual talent is politics.

Something is 'simple' if it's smaller. A system that has 1 thing in it is simpler than a system that has 2 things in it. Simplicity must be coupled with Occam's razor - that out of several comparably powerful alternatives, we should pick the simplest one.

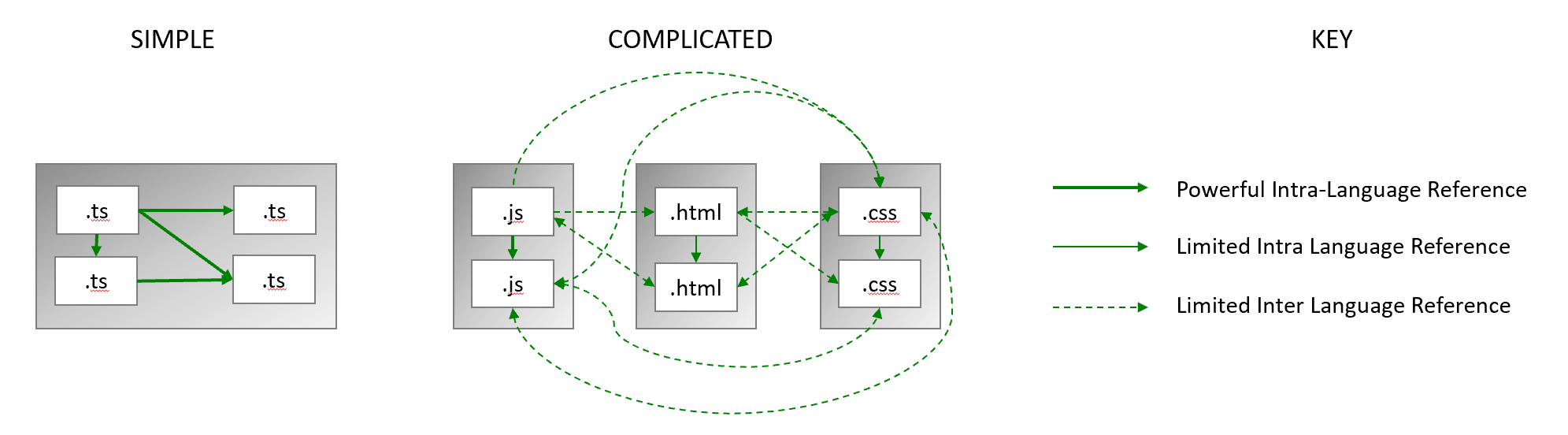

Solenya is simple because it:

- Reduces the number or languages to get the job done

- Removes the need for an extra bolt-on state manager

without sacrificing any power.

Solenya, in part thanks to the excellent typestyle library, uses typescript to express everything, including HTML and CSS. This substantially reduces complexity.

In comparison, most front end frameworks, despite putatively being "unified" development models, encourage development in 3 different languages: Javascript for application code, HTML for UI, and CSS for styling. This slows development down immeasurably, due to:

- Limited abstractions in the languages

- HTML and CSS are in reality used as impoverished unwieldy programming languages

- Limited interop between languages

- You can't for example parameterise some CSS style with an instance of a typescript class

- Using multiple of anything, when a single thing will do

- Especially when that thing is an entire language

Rather than addressing the root of the problem, populist solutions appeal to developer tradition, doubling down on the flawed approach with more ad-hoc abstractions. "New" slightly-less-impoverished languages are built on top of the impoverished languages. Yet-another-template language reinventing looping constructs, or a layer of top of CSS where we're thrilled we get a feature like... variables.

Another excuse for using 3 languages rather than 1 is the misnomer that this helps separate concerns. Separation of languages != separation of concerns. In fact, the worst thing you can do if you care about separating concerns is to attempt to do so with a language lacking abstractions that make such separations possible. This is why css code bases (and scss) are littered with repetition, with tooling-invisible two-way dependencies with their accompanying code and HTML.

Solenya was built from the ground-up to take advantage of static typing.

Static typing gives you: the best possible testing for free, where the compiler constrains the possible values of your variables. Great tooling. Free documentation. It makes other people's code much easier to understand. And it makes your own code easier to understand as and when you refactor it.

It's easier to scale a large code base with static typing. It's why Facebook developed their own statically typed version of PHP. It's why Typescript exists. And the tax of static typing in modern languages is really low, thanks to type inference. There's increasingly few excuses for eschewing compile-time types!

Typescript, as well as other languages like F#, do a brilliant job of leveraging both the OO and functional paradigms. Solenya, being written in and for Typescript, takes full advantage of this.

Unfortunately, some of the alternatives to the big frameworks are anti-OO frameworks. Their tenets? That state mutation is always wrong. That coupling functions and data is always wrong. Yet their own code demonstrates rampant DRY violations and convoluted higher-order write-only functions. You know, the functions that return functions that return functions that return functions, where oh, yes, well the 2nd innermost function actually did store state. Good luck debugging that.

To manage complexity in a web application, we split it into modular chunks. It's helpful to think of common types of chunks, or "components", in terms of their statefulness:

- Objects with application state (i.e. a high level chunk of an application).

- Pure functions that return a view (i.e. a stateless virtual dom node)

- Objects with DOM state (i.e. essentially a web component)

Most web frameworks today focus on building components of type '2' and '3', not type '1' components - but this causes serious problems.

The immediate strategy, which is really a lack of strategy, or upside-down strategy, is to use a type '3' component, an abstraction around an HTML DOM element, and then polute it with application logic. In code samples, and in small applications, we can get away with this dirty ad-hoc approach, but the approach doesn't scale.

For this reason, many people eventually adopt the strategy of using a separate state management library to get their type '1' components. But now you've got two separate component models to deal with and integrate.

Solenya is designed from the start for building high-level type '1' components. This means you can cleanly organise your application into meaningful, reusable, high-level chunks. So for example, you could have a component for a login, a component for a paged table, or a component for an address. And you can compose components to any scale: in fact your root component will represent your entire application.

Each component's view is a pure function of its state, so within each component we get a high degree of separation of the application logic/state and the view. In fact, for any solenya application, you can strip out its views, and the core structure of the application remains in tact. Writing a component means thinking about its state and state transitions first, and its views second. This approach makes solenya components innately serializable. So another way to think about solenya components is that they represent the serializable parts of your application, that you might want to load and save from and to local storage or the server.

The Component and App APIs have been covered in earlier sections, and can also be understood through intellisense and the source code, but are included here to give a reference-oriented overview.

The HTML, lifecycle, serialization, and time travel APIs have already been covered in their dedicated sections.

/** Override to return a virtual DOM element that visually represents the component's state */

view(): VElement

/** Call to run an action after the view is rendered. Think of it like setTimeout but executed at exactly at the right time in the update cycle. */

onRefreshed (action: () => void) /** Called after construction, with a flag indicating if deserialization occured */

attached (deserialized: boolean)

/** Attaches a component to the component tree.

* Called automatically on refresh but can be explicitly called to eagerly attach.

*/

attach (app: App, parent?: Component)/** Call with action that updates the component's state, with optional payload */

update (updater: () => void, payload: any = {})

/** Override to listen to an update after its occured

* @param payload Contains data associated with update - the update method will set the source property to 'this'

*/

updated (payload: any) : void/** The app associated with the component; undefined if not yet attached - use judiciously - main purpose is internal use by update method */

app?: App

/** The parent component; undefined if the root component - use judiciously - main purpose is internal use by update method */

parent?: Component

/** Returns the root component by recursively walking through each parent */

root () : Component

/** Returns the branch, inclusively from this component to the root component */

branch () : Component[]

/** Returns the properties that are components, flattening out array properties of components */

children () : Component[] /**

* The entry point for a solenya app

* @param rootComponentConstructor The parameterless constructor of the root component

* @param containerId The element id to render the view, and local storage name

* @param rootComponent Optionally, an existing instance of the root component

* @param isVdomRendered Optionally, indicate that the vdom is already rendered

*/

constructor (

rootComponentConstructor : new() => Component,

containerId: string,

rootComponent?: Component,

isVdomRendered = false

)

/** Root component of updates, view and serialization */

rootComponent: Component /** Manages serialization of root component to local storage */

storage: Storage

/** manages time travel - type is 'any' because component snapshots are converted to plain json objects */

time: TimeTravel<any>

/** whether snapshots occur by default after each update */

timeTravelOn: boolean

/**

* Serialize the root component to local storage and/or time travel history

* @param doSave true = force save, false = do not save, undefined = use value of App.storage.autosave

* @param doTimeSnapshot true = force snapshot,false = do not snapshot, undefined = use value of App.timeTravelOn

*/

snapshot(doSave?: boolean, doTimeSnapshot?: boolean): void