The assignment is due Feb 27 (Monday), at 11:59 PM.

Please zip the following files and upload your zipped file to Gradescope.

shading/srcfolder- writeup (.txt, .doc, .pdf)

One team only needs one submission, please tag your teammates in your submission.

Please submit a short document explaining what you have implemented, and any particular details of your submission. If your submission includes any implementations which are not entirely functional, please detail what works and what doesn't, along with where you got stuck. This document does not need to be long; correctly implemented features may simply be listed, and incomplete features should be described in a few sentences at most.

In this assignment, you are a given a simple real-time renderer and a simple 3D scene. However, the starter code implements only very simple material and lighting models, so rendered images do not look particularly great. In this assignment, you will improve the quality of the rendering by implementing a number of lighting and material shading effects using the GLSL, OpenGL's shading language, as well as some OpenGL client code in C++. The point of this assignment is to get basic experience with modern shader programming, and to build understanding of how material pattern logic, material BRDFs, and lighting computations are combined in a shader to compute surface reflectance. There are countless ways you can keep going by adding more complex materials and lighting. This is will be great fodder for final projects. We are interested to see what you can do!

In order to ease the process of running on different platforms, we will be using CMake for our assignments. You will need a CMake installation of version 2.8+ to build the code for this assignment. It should also be relatively easy to build the assignment and work locally on your OSX or 64-bit version of Linux or Windows. The project can be run by SSH'ing to rice.stanford.edu with your SUNet ID, password, and two-step authentication (remember to turn on X11 forwarding). The project requires OpenGL version 3.0+.

If you are working on OS X and do not have CMake installed, we recommend installing it through Homebrew: $ brew install cmake. You may also need the freetype package $ brew install freetype.

If you are working on Linux, you should be able to install dependencies with your system's package manager as needed (you may need cmake and freetype, and possibly others). You may need to check that you are using X.Org and not Wayland (the default in non-LTS Ubuntu releases), or the compiled binary may crash immediately.

$ sudo apt-get install libfreetype6

$ sudo apt-get install libfreetype6-dev

$ sudo apt-get install libglu1-mesa-dev

$ sudo apt-get install xorg-dev

$ cd shading && mkdir build && cd build

$ cmake ..

$ make

These 3 steps (1) create an out-of-source build directory, (2) configure the project using CMake, and (3) compile the project. If all goes well, you should see an executable render in the build directory. As you work, simply typing make in the build directory will recompile the project.

You need to install the latest version of CMake and Visual Studio. Visual Studio Community is free.

After installing CMake and Visual Studio, let's start with building in CMake. Replace SOURCE_DIR to the cloned directory (shading/ in our case, NOT src/), and BUILD_DIR to draw-svg/build.

Then, press Configure button, select Visual Studio 17 2022 for generator and x64 for platform, and you should see Configuring done message. Then, press Generate button and you should see Generating done.

This should create a build directory with a Visual Studio solution file in it named Render.sln. You can double-click this file to open the solution in Visual Studio.

If you plan on using Visual Studio to debug your program, you must change render project in the Solution Explorer as the startup project by right-clicking on it and selecting Set as StartUp Project. You can also set the command line arguments to the project by right-clicking render project again, selecting Properties, going into the Debugging tab, and setting the value in Command Arguments. If you want to run the program with the test folder, you can set this command argument to ../../media/spheres/spheres.json. After setting all these, you can hit F5\press Local Windows Debugger button to build your program and run it with the debugger.

You should also change the build mode to Release from Debug occasionally by clicking the Solution Configurations drop down menu on the top menu bar, which will make your program run faster. Note that you will have to set Command Arguments again if you change the build mode. Note that your application must run properly in both debug and release build.

Note: to avoid the linking error when building x64 (e.g. LNK4272: library machine type 'x86' conflicts with target machine type 'x64', LNK1104: cannot open file freetype.lib.), please make the following changes to your shading project properties (right click render project in the Solution Explorer sidebar to open Properties).

Properties -> Linker -> Input -> edit -> change freetype.lib to freetype_win64.lib

A table of all the keyboard controls in the application is provided below.

| Command | Key |

|---|---|

| Print camera parameters | 'C' |

| Visualize Shadow Map | 'V' |

| Disco Mode (Dancing Spotlights) | 'D' |

| Hot reload all shaders | 'S' |

To complete this assignment, you'll be writing shaders in a language called GLSL (OpenGL Shading Language). GLSL's syntax is C/C++ "like", but it features a number of built in types specific to graphics. In this assignment, there are two shaders, a vertex shader src/shader/shader.vert that is executed once per vertex of each rendered triangle mesh. And a fragment shader src/shader/shader.frag that executes once per fragment (a.k.a. once per screen sample covered by a triangle.)

We didn't specifically talk about the specifics of GLSL programming in class, so you'll have to pick it up on your own. Fortunately, there are a number of great GLSL tutorials online, but we recommend The Book of Shaders. Here are a few things to know:

-

You'll want to start by looking at

main()in bothshader.vertandshader.frag. This is the function that executes once per vertex or once per fragment. -

Make sure you understand the difference between uniform parameters to a shader, which are read-only variables that take on the same value for all invocations of a shader, and varying values that assume different values for each invocation. Per-vertex input attributes (parameters declared with the

intype qualifier) are inputs to the vertex shader that have a unique value per vertex (such as position, normal, texcoord, etc.). The vertex's shader's varying outputs (outtype qualifier) are interpolated by the rasterizer, and then the interpolated values are provided as inputs (with theinqualifier) to the fragment shader when it is invoked for a specific surface point. Notice how the name of the vertex shader's output variables matches the name of the fragment shader's varying input variables. -

The assignment starter code "just-in-time" (JIT) compiles your GLSL vertex and fragment shaders on-the-fly when the

renderapplication starts running. Therefore, you won't know if the code successfully compiles until run time. If you see a black screen while rendering, it's likely because your GLSL shader failed to compile. Look to your console for error messages about a failed compile.

The client C++ code that makes OpenGL library commands can be quite complicated. Luckily for this assignment, we have abstracted away the messy details of using the OpenGL libreary to a couple of relatively simple APIs in the GLResourceManager and Shader classes. You will need to look at their header files as well as the example calls in the starter code to see how they can be used. For the adventurous, we encourage you to look at the implementations of these two classes to get a sense on how to use OpenGL, since extra-credit or final project extensions of this assignment likely need to delve deeper.

In the first part of this assignment you will enable interactive inspection of the scene by deriving the correct transformation matrix from world space to camera space. To begin, render the spheres scene using the command:

./render ../media/spheres/spheres.json

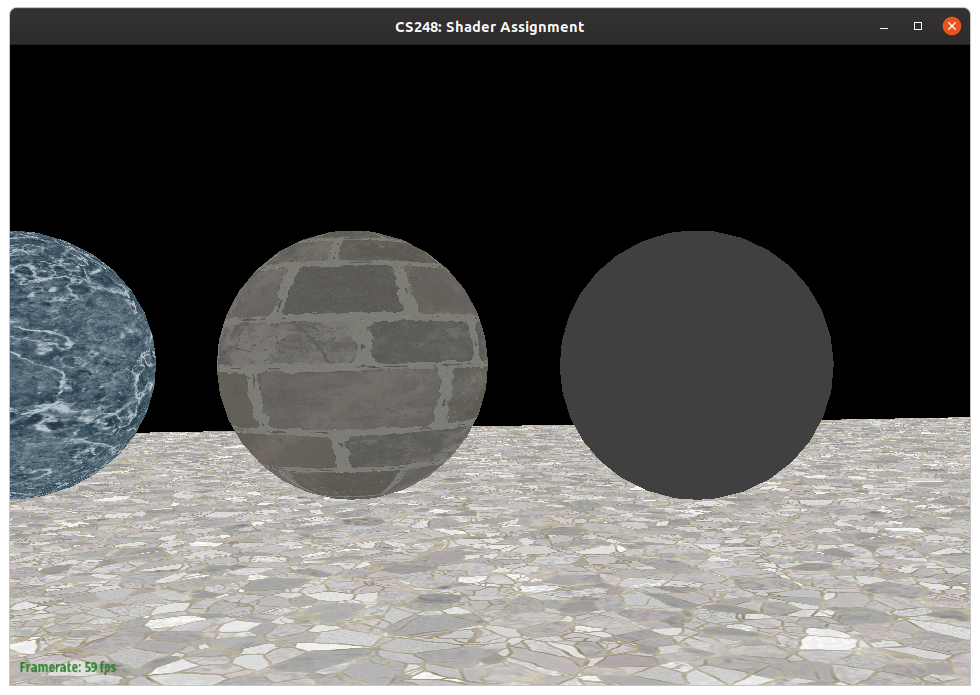

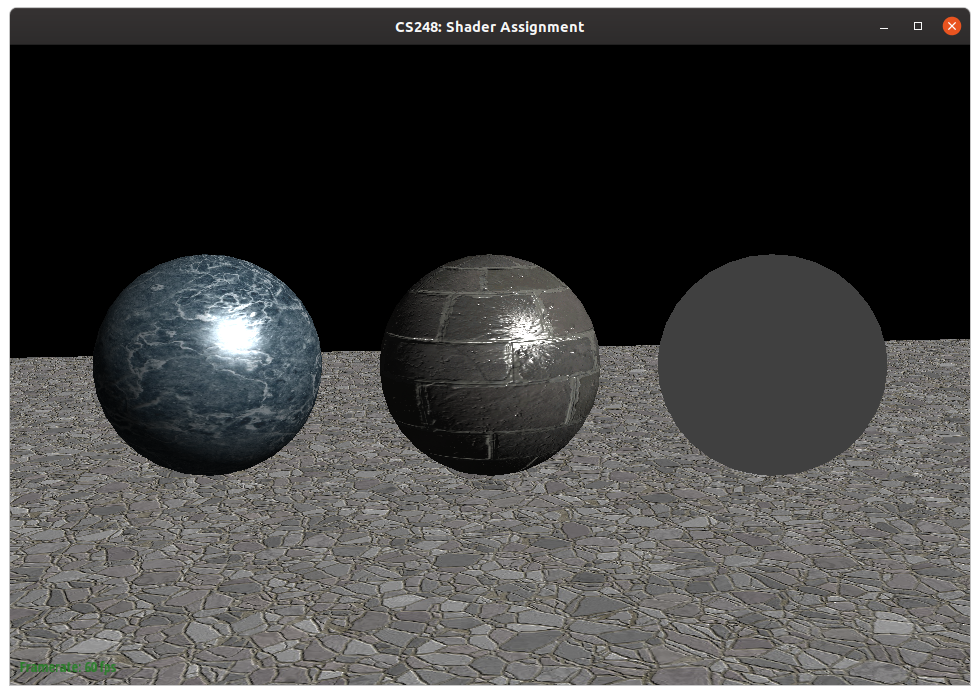

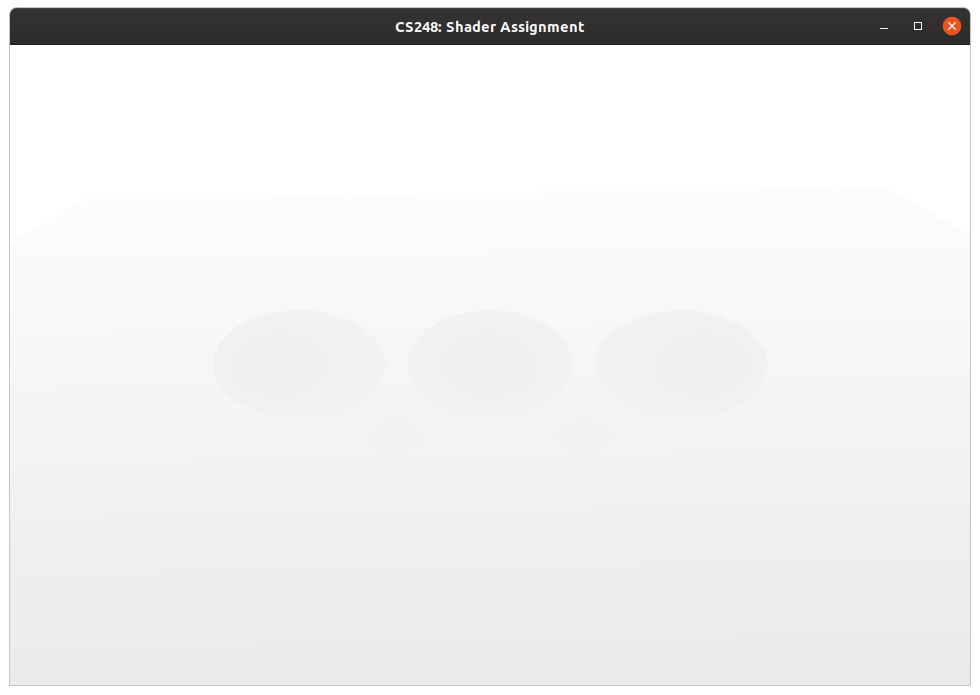

You should see an image that looks a bit like the one below:

IMPORTANT: If you see a black screen it means your GL environment is not working correctly. Please reach out to course staff for help on getting it set up! Be prepared to provide us with the console error logs.

What you need to do: src/dynamic_scene/scene.cpp:Scene::createWorldToCameraMatrix()

Notice that when you run render, mouse controls like scrolling to rotate the camera or, left/right click-drag do nothing. This is because the starter code does not correctly implement the world space-to-camera space transformation. Implement Scene::createWorldToCameraMatrix() in src/dynamic_scene/scene.cpp.

Your task is to derive the correct matrix to enable interactive inspection of the scene. Careful: CS248::Matrix is in column major.

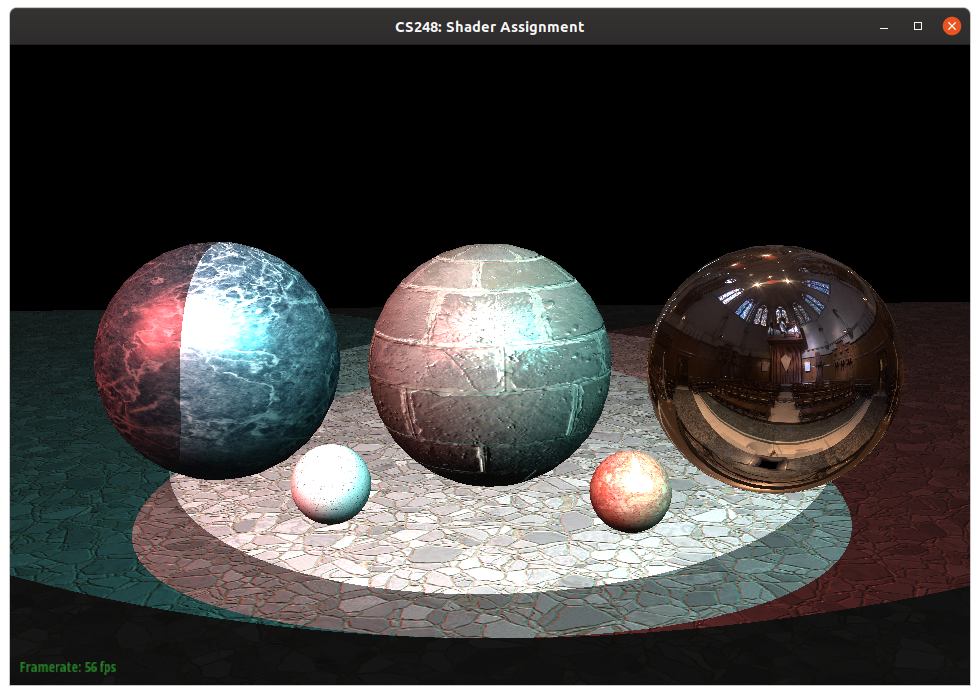

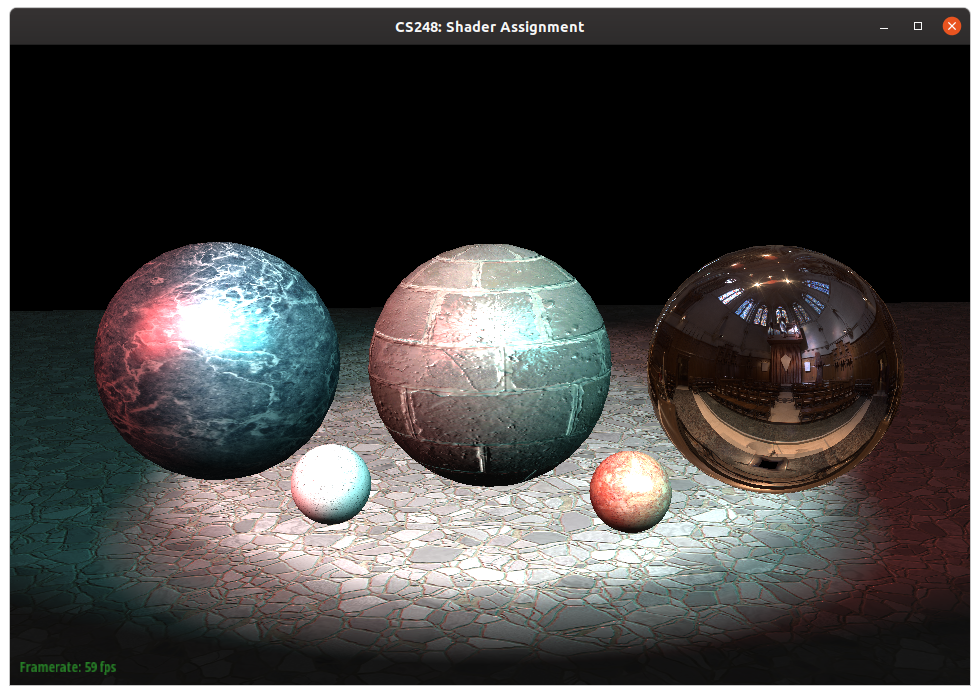

A correct implementation will yield the following view, and allow interactive inspection with the mouse!

In the later parts of this assignment you will implement two important aspects of defining a material. First, you will implement a simple BRDF that implements the phong reflectance model to render a shiny surface.

What you need to do: src/shader/shader.frag

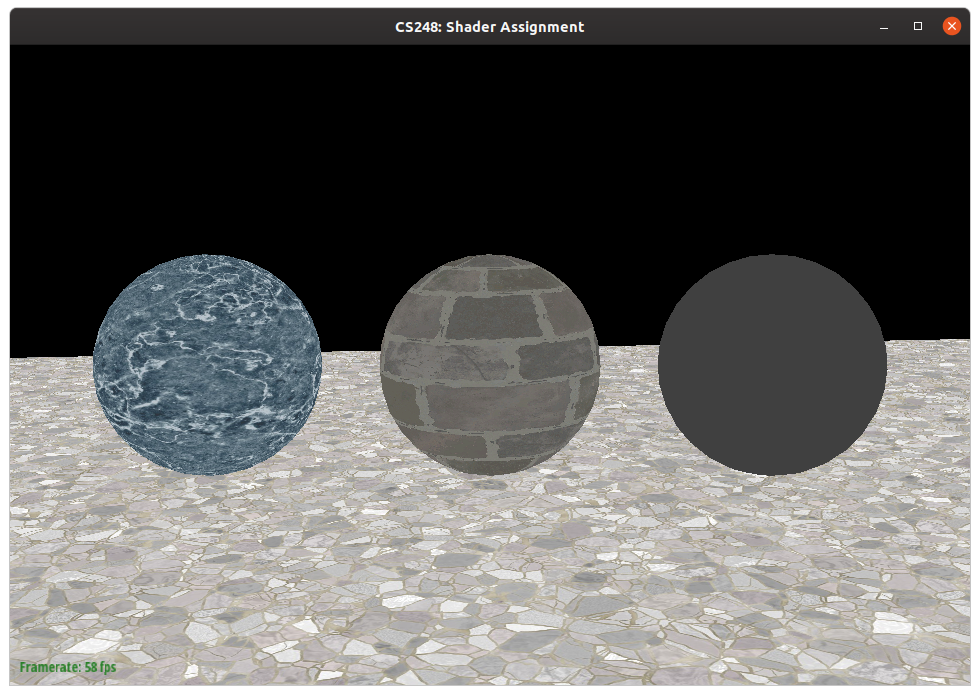

Notice that the scene is rendered with a texture map on the ground plane and two of the three spheres, but there is no lighting in the rendering. To add basic lighting, we'd like you to implement Phong_BRDF() in src/shader/shader.frag. This function should implement the Phong Reflectance model. Your implementation should compute the diffuse and specular components of this reflectance model in Phong_BRDF(). Note that the ambient term is independent of scene light sources and should be added in to the total surface reflectance outside of the light integration loops (the starter code already does this).

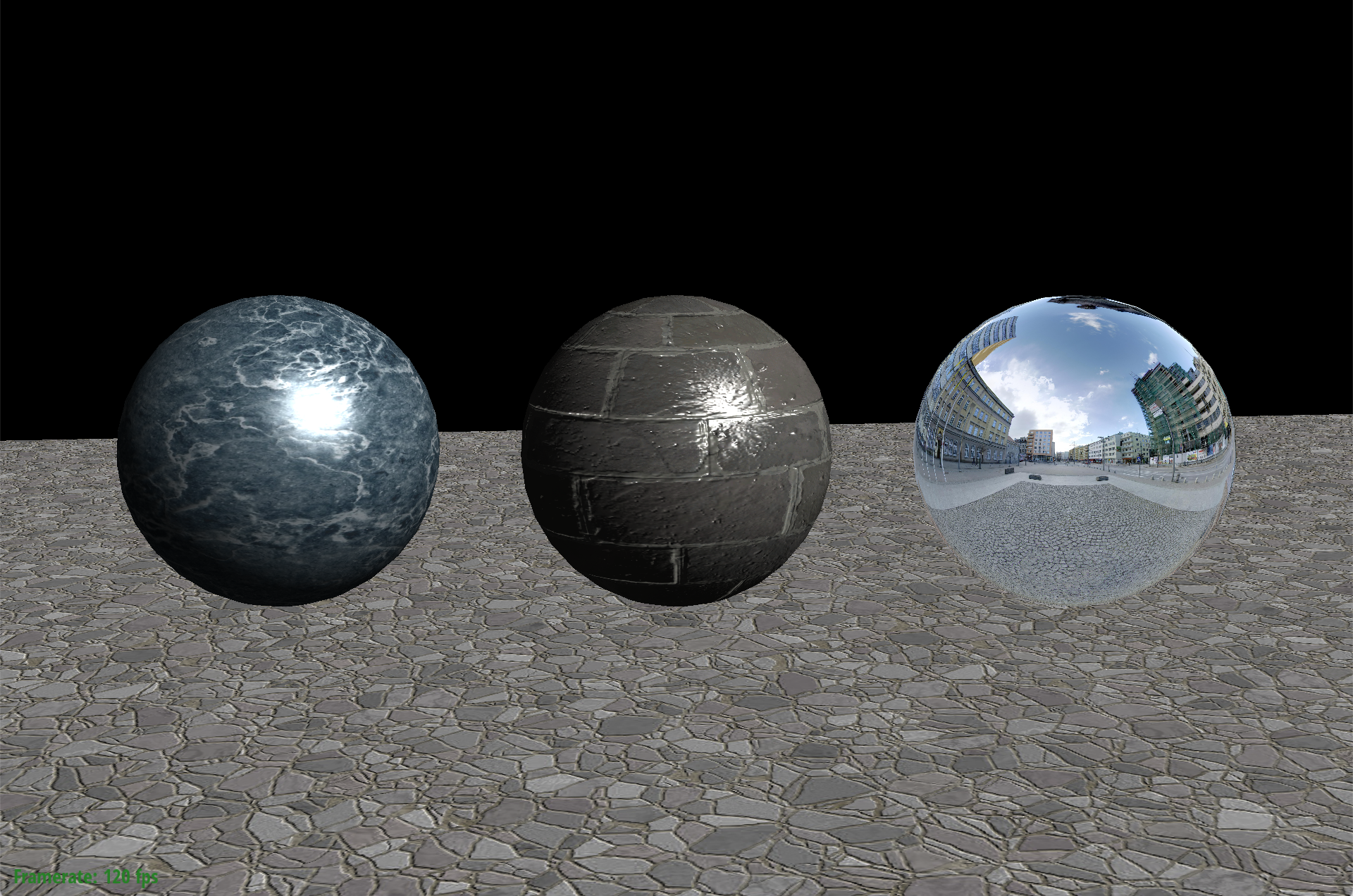

A correct implementation of Phong reflectance should yield shaded spheres, which should look like this.

NOTE: You can press the S key at any type when running the render application to "hot reload" your vertex and fragment shaders.. You do not need to quit the program to see changes to a shader! Yes, you can thank the staff later. ;-)

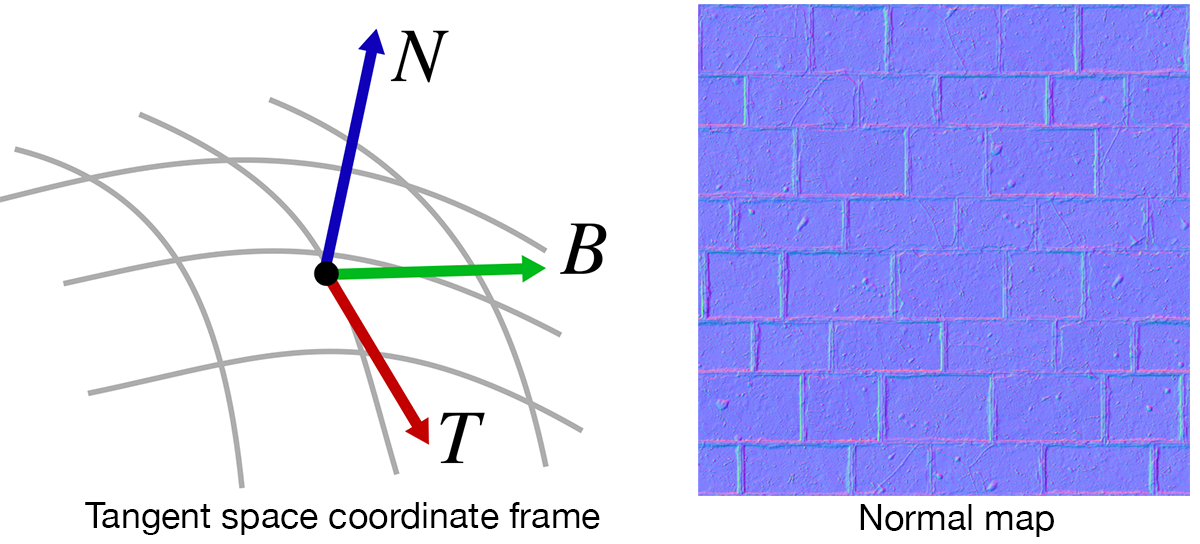

Although there is a texture map on the ground plane and spheres to add detail to these surfaces, the surfaces continue to look "flat". Your next task to implement normal mapping to create the illusion of a surface having more detail that what is modeled by the underlying geometry. They idea of normal mapping is to perturb the surface's geometric normal with an offset by a vector encoded in a texture map. An example "normal map" is shown at right in the image below.

Each RGB sample in the "normal map" encodes a 3D vector that is a perturbation of the geometry's actual normal at the corresponding surface point. However, instead of encoding this offset in single coordinate space (e.g, object space or world space), the vectors in the normal map are represented in the surface's tangent space. Tangent space is a coordinate frame that is relative to the surface's orientation at each point. It is defined by the surface's normal, aligned with the Z-axis [0 0 1] in tangent space, and a tangent vector to the surface, corresponding to X-axis [1 0 0]. The tangent space coordinate frame at a point on the surface is illustrated at left in the figure above.

Normal mapping works as follows: given a point on the surface, your shader needs to sample the normal map at the appropriate location to obtain the tangent space normal at this point. Then the shader should convert the tangent space normal to its world space representation so that the normal can be used for reflectance calculations.

What you need to do: src/shader/shader.vert src/shader/shader.frag src/dynamic_scene/mesh.cpp:Mesh::internalDraw()

First, modify the vertex shader shader.vert to compute a transform tan2World. This matrix should convert vectors in tangent space back to world space. You should think about creating a rotation matrix that converts tangent space to object space, and then applying an additional transformation to move the object space frame to world space. The vertex shader emits tan2World for later use in fragment shading.

- Notice that in

shader.vertyou are given the normal (N) and surface tangent (T) at the current vertex. But you are not given the third vector, often called the "binormal vector" (B) defining the Y-axis of tangent space. How do you compute this vector given the normal and tangent? - How do you create a rotation matrix that takes tangent space vectors to object space vector? See this slide for a hint.

Second, in shader.frag, you need to sample the normal map, and then use tan2World to compute a world space normal at the current surface sample point.

Third, in the starter code, the normal map is not yet passed into the shader by the application. There are two steps that you need to perform to do this. First, you will need to modify the C++ code (the "caller") to pass a texture object to the fragment shader (the callee). Second, you'll need to declare a new uniform input variable in the shader.

First step, take a look at the code in Mesh::internalDraw() in mesh.cpp. This is the C++ that makes OpenGL commands to draw the mesh. Notice all the shader_->set* calls at the top of this function. These calls pass arguments to the shader. (In OpenGL terminology, they are "binding" parameters like uniform variables and textures to the shader program.)

Take a look at how the C++ starter code binds the diffuse color texture object to the shader. (Look for this line):

if (doTextureMapping_)

shader_->setTextureSampler("diffuseTextureSampler", diffuseTextureId_);

Second step, you'll need to extend the code to also bind the normal map texture (given by normalTextureId_) to the shader in shader.frag. Follow the example of diffuseTextureSampler to declare a corresponding texture sampler parameter in shader.frag and bind the prepared texture to that using the handle normalTextureId_. After successfully passing the normal map to the fragment shader, you can modify shader.frag to sample it and compute the correct normal.

We recommend that you debug normal mapping on the sphere scene (media/spheres/spheres.json).

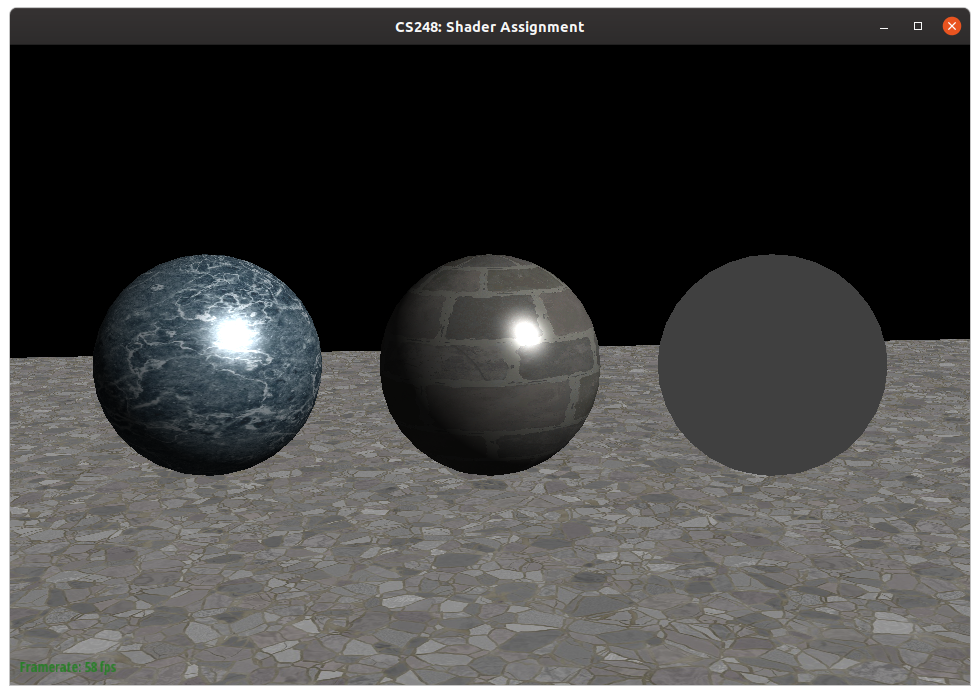

Without normal mapping, the sphere looks like a flat sphere with a brick texture, as shown previously. But with normal mapping, notice how the bumpy surface creates more plausible reflective highlights in the rendering on the right.

With a correct implementation of normal mapping the scene will look like this:

Note: After getting part 3 working, this is a good time to stop and take a look at some of the details of the implementation of gl_resource_manager.cpp to see the behind the curtain details of how texture objects are created using OpenGL and how parameters are bound to the GL pipeline.

So far, your shaders have used simple point and directional light sources in the scene. (Notice that in shader.frag the code iterated over light sources and accumulated reflectance.) We'd now like you to implement a more complex form of light source. This light source, called an image based environment light, described here in lecture represents light incoming on the scene from an infinitely far source, but from all directions. Pixel (x,y) in the texture map encodes the magnitude and color and light from the direction (phi, theta). Phi and theta encode a direction in spherical coordinates.

What you need to do: src/shader/shader.frag src/dynamic_scene/mesh.cpp:Mesh::internalDraw()

In src/shader/shader.frag, we'd like you to implement a perfectly mirror reflective surface. The shader should reflect the vector from the surface to the camera about the surface normal, and the use the reflected vector to perform a lookup in the environment map. A few notes are below:

- Just like with normal mapping, the environment map is not yet passed into the shader. Similar to what you did in normal mapping, you need to bind the environment texture map with handle

environmentTextureId_to a texture sampler parameter inshader.frag. Recall this is done by making edits toMesh::internalDrawand adding an additional sampler variable to the fragment shader. dir2camerainshader.fragconveniently gives you the world space direction from the fragment's surface point to the camera. It is not normalized.- The function

vec3 SampleEnvironmentMap(vec3 D)takes as input a direction (outward from the scene), and returns the radiance from the environment light arriving from this direction (this is light arriving at the surface from an infinitely far light source from the direction -D). - To perform an environment map lookup, you have to convert the reflection direction from its 3D Euclidean representation to spherical coordinates phi and theta. In this assignment rendering is set up to use a a right-handed coordinate system (where Y is up, X is pointing to the right, and Z is pointing toward the camera), so you'll need to adjust the standard equations of converting from XYZ to spherical coordinates accordingly. Specifically, in this assignment, the polar (or zenith) angle theta is the angle between the direction and the Y axis. The azimuthal angle phi is zero when the direction vector is in the YZ plane, and increases as this vector rotates toward the XY plane. Be careful about the range of these two angles.

- Some thing to keep in mind (to help you debug) are that phi is 0 when it is aligned with our Z axis, and phi is pi/2 when the direction is aligned with our X axis. This means as revolve about the Y axis, counterclockwise, starting from pointing in the Z axis direction, moving towards the X axis and then the negative Z direction and so on, you will be increasing phi from [0, 2PI]. This means that the data in the environment map needs to be flipped (vertically) in order to follow our right hand convention. One way to solve with would be to directly edit the environment map (ie. the png file), however instead we ask you perform this during runtime. You can do this by computing phi as before and just passing in (2PI - phi) when performing the texture lookup.

Once you've correctly implemented an environment map lookups, the rightmost sphere will look as if it's a perfect mirror.

You'll also be able to render a reflective teapot (media/teapot/teapot.json), as shown below.

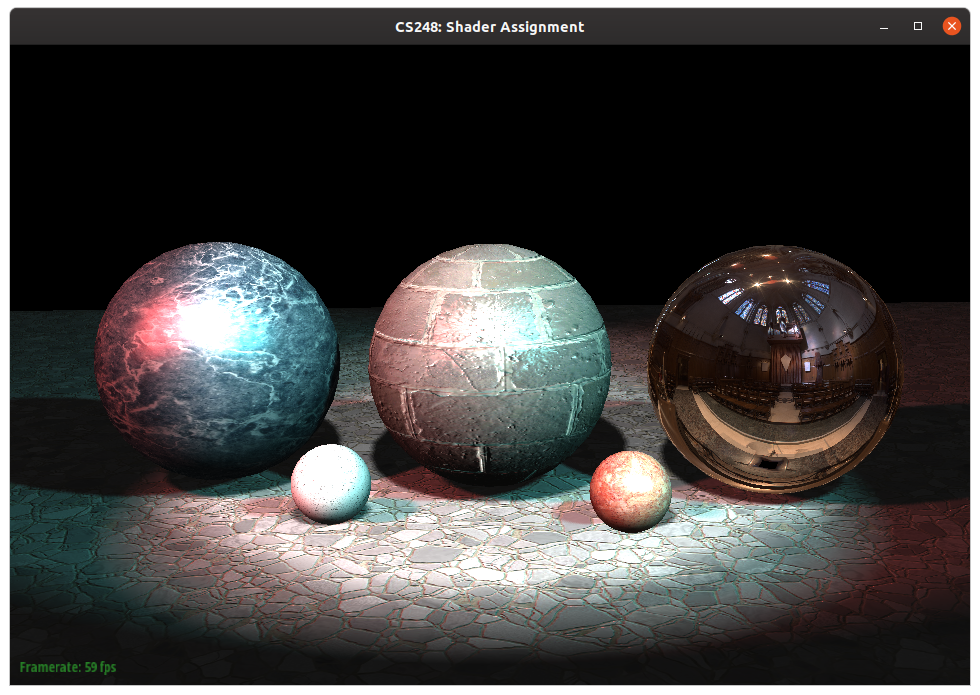

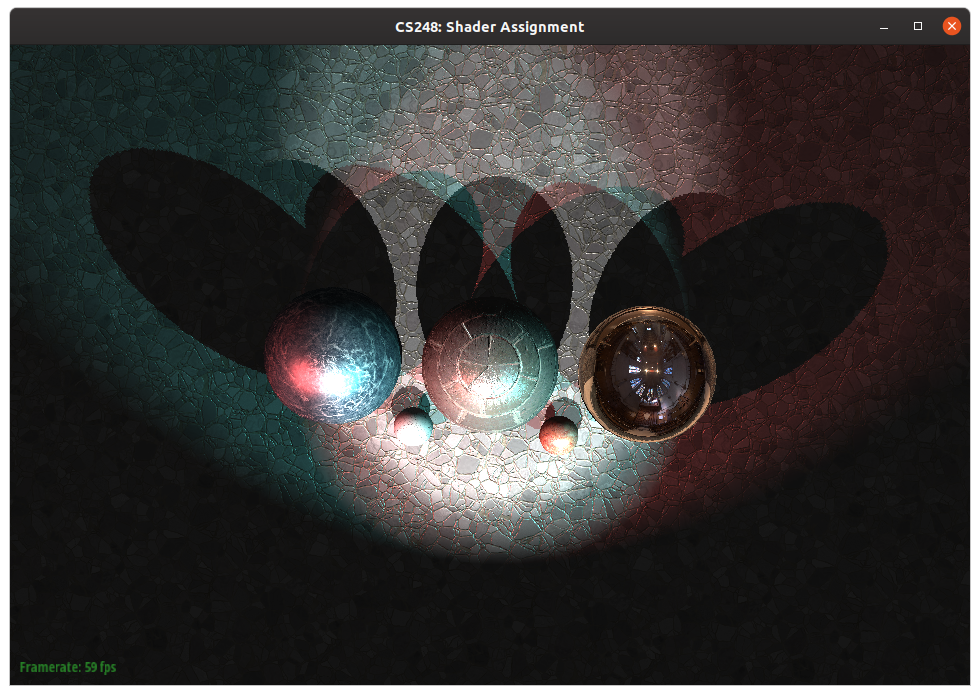

In the final part of this assignment you will implement a more advanced type of light source, a spotlight, as well as use shadow mapping to compute smooth shadows for your spotlights. These more advanced lighting conditions will significantly improve the realism of your rendering. When you are done with this part of the assignment, you will be able to render the scene media/spheres/spheres_shadow.json to get a rendering like this:

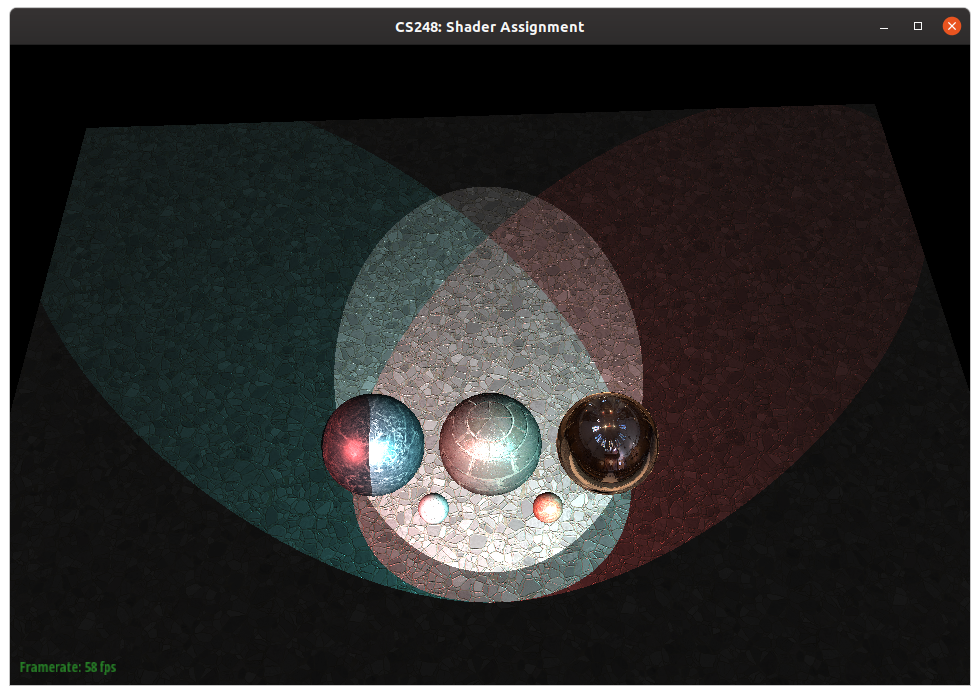

The scene is illuminated by three spotlights, a red spotlight coming from the front-left of the scene, and a white spotlight coming from the front, and a cyan spotlight from front-right. The image below is a view from above the scene.

The first step in this part of the assignment is to extend your fragment shader for rendering spotlights. You will need to modify src/shader/shader_shadow.frag for this task. Note that if you have completed Parts 1-3 of the assignment, you can drop your solutions from shader.vert and shader.frag into this file so that you can render media/spheres/spheres_shadow.json with correct texture mapping, normal mapping, and environment lighting.

What you need to do: src/shader/shader_shadow.frag

- Modify the

shader_shadow.fragto compute the illumination from a spotlight by adding code to the body of the loop over spotlights. Details about the implementation are in the starter code, but as a quick summary, a spotlight is a light that has non-zero illumination only in directions that are withincone_angleof the light direction. Note that the intensity of a spotlight falls off with a 1/D^2 factor (where D is the distance from the light source). If you implement this logic, you should see an image that looks like the one below. In the image below, notice how the intensity of the spotlight falls off with distance.

- Notice that since your implementation of spotlights cuts off all illumination beyond the cone angle, the spotlights feature a hard boundary between light and dark. You can soften this boundary by linearly interpolating illumination intensity from near the edge of the cone. Please see details in the code, but in our reference solution, intensity of the spotlight starts falling off once the angle to the surface point is at least 90% of the cone angle, and drops to zero illumination at 110% of the cone angle. With this smoother spotlight falloff you will see an image like this.

Now you will improve your spotlights so they cast shadows. In class we discussed the shadow mapping algorithm for approximating shadows in a rasterization-based rendering pipeline. Recall that shadow mapping requires two steps.

- In step 1, for each light source, we render scene geometry using a camera that is positioned at the light source. The result of rendering the scene from this vantage point is a depth buffer encoding the closest point in the scene at each sample point. This depth buffer will be used as a single channel texture map provided to a fragment shader in step 2.

- In step 2, when calculating illumination during rendering (when shading a surface point), the fragment shader must compute whether the current surface point is in shadow from the perspective of the light source. To do this, the fragment shader computes the coordinate of the current scene point in the coordinate system of a camera positioned at the light (in "light space"). It then uses the (x,y) values of this "light space" coordinate to perform a lookup into the shadow map texture. If the surface is not the closest scene element to the light at this point, then it is in shadow.

What to do in C++ client code: src/dynamic_scene/mesh.cpp:Mesh::internalDraw() src/dynamic_scene/scene.cpp:Scene::renderShadowPass()

We have created a seperate framebuffer for each spotlight. For each light the C++ code will render the scene from the perspective of the light into this framebuffer. (This is often called a "shadow map generation pass", or a "shadow pass". The term "pass" is jargon that refers to a pass over all the scene geometry when rendering.) Handles for these per shadow map framebuffers are stored in shadowFrameBufferId_.

In Scene::renderShadowPass, you need to configure OpenGL to render to the correct framebuffer when performing shadow map generation passes.

You also need to compute the correct view and perspective projection matrix for the shadow pass rendering. You might want to look at Scene::render for an example of how view and perspective projection matrices are set-up for the final rendering from the perspective of the real scene camera.

Finally, you need to compute and store a worldToShadowLight matrix for every light that goes from world space to "light space". More details are in the starter code.

You might be wondering what is the definition of the "light space"? It is a coordinate space where the virtual camera is at the position of the spotlight, looking directly in the direction of the spotlight, and after applying perspective projection. You need to adjust the transform so that after homogeneous divide vertices that fall on screen during shadow map rendering are in the [0,1]^2 range and valid scene depths between the near and far clipping planes are in the [0-1] range. You encourage you to read more about the coordinate systems of shadow mapping here.

We have set-up the shadow textures as an Array Texture that connects to the shadow-pass frame buffers. Once you have set-up the client code correctly, you should be able to visualize the depth map (for the first spotlight) that you generate from your shadow pass pressing 'v'.

The last step in the client code is to pass the array texture that is written to during the shadow map generation passes as an input texture to the fragment shader (for sampling from) that is used in the final render pass that actually renders the scene. (Recall these bindings are set up in Mesh::internalDraw, as you have done twice now with normal map and environment map.)

Sampling from Array Textures in the GLSL fragment shader requires a slightly different syntax. Look in Scene::visualizeShadowMap and src/shader/shadow_viz.frag to see how to use it.

In Mesh::internalDraw, you also need to pass your shaders an array of matrices representing object space to "light space" transforms for all shadowed lights. See starter code for details.

What to do in the vertex shader: src/shader/shader_shadow.vert

Your work in the vertex shader is quite easy. Just transform the triangle vertex positions into light space, create new vertex shader output variables for them to pass into the fragment shader.

What to do in the fragment shader: src/shader/shader_shadow.frag

Your work in the fragment shader is a bit more complex. The shader receives the light space homogenous position of the surface (we called it position_shadowlight in reference solution), and must use this position to determine if the surface is in shadow from the perspective of this light. Since the position is in 3D-homogeneous coordinates, you first need to extract a non-homogeneous XY via the homogeneous divide:

vec2 shadow_uv = position_shadowlight.xy / position_shadowlight.w;

Now you have a screen-space XY that you can use to sample the shadow map, and obtain the closest scene point at this location. You will need to test the value returned by the texture lookup against the distance between the current surface point and the light to determine if the surface is in shadow. (How do you compute this?)

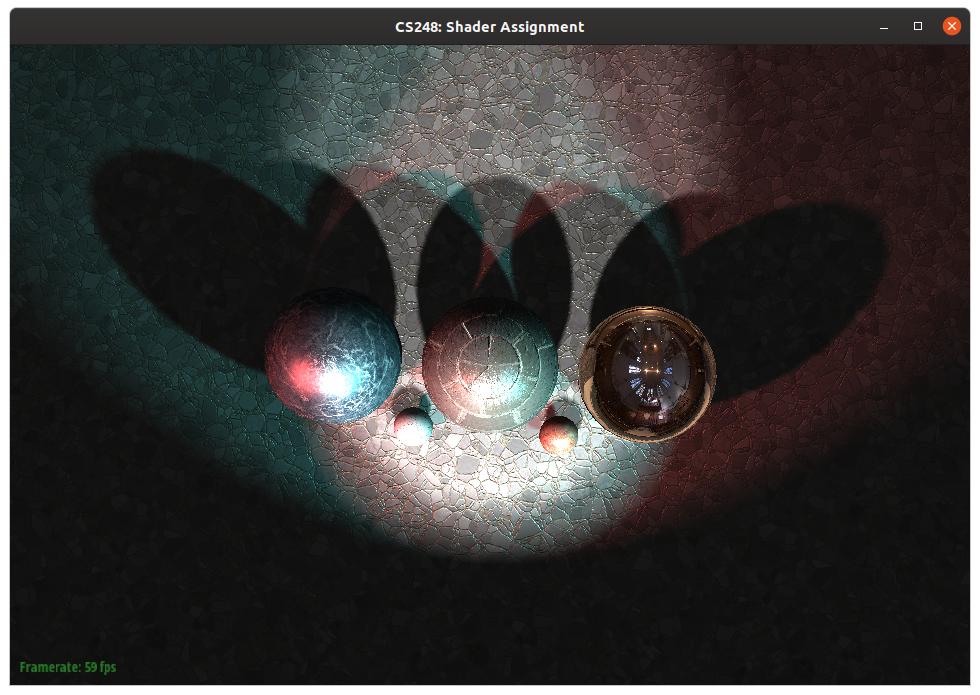

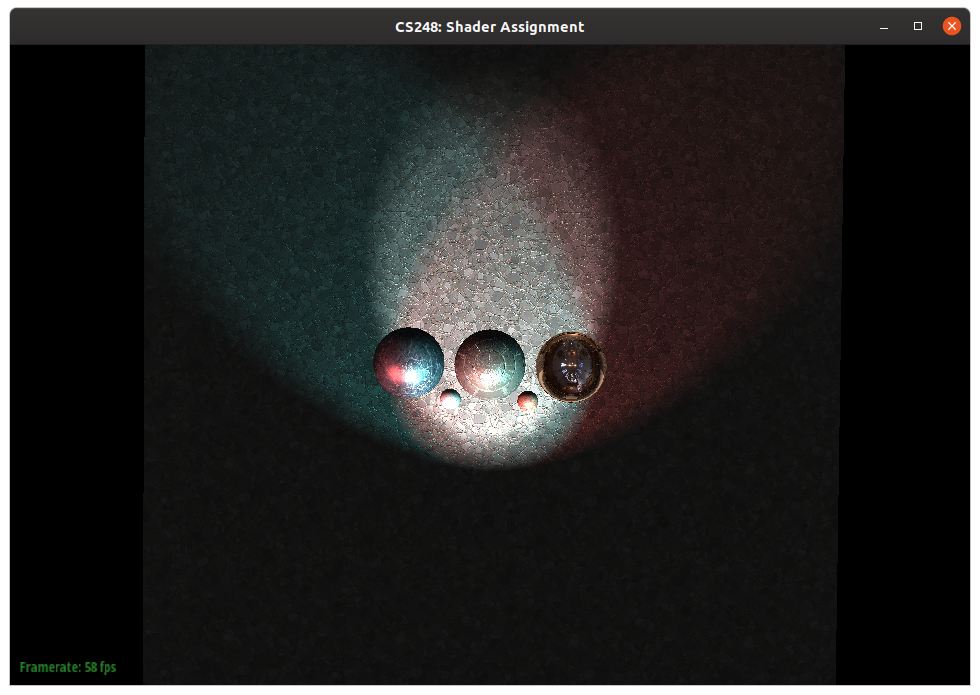

At this point, you may notice errors in your image. Read about the phenomenon of "shadow acne" and correct any artifacts by adding a bias term to your shadow distance comparison. Biasing pushes the surface being tested closer to the light so that only surfaces a good bit closer to the light can cast shadows on the current surface. At this point, with a properly biased shadow test (the reference solution uses a quite large bias value of 0.005), you should get an image that looks like this (shown from a top view):

As you move the camera and look at the scene from different viewpoints, you might observe aliasing (jaggies) at the edges of your shadows. One way to approximate a smoother shadow boundary is to take multiple samples of the shadow map around a desired sample point, and then compute the fraction of samples that pass the test. This technique, which is quite costly because it requires making multiple texture lookups (a form of supersampling), is called percentage closure filtering (PCF). Inuitively, by perturbing the location of the shadow map lookup, PCF is trying to determine how close to a shadow boundary the current surface point is. Points slower to the boundary are considered to be partially occluded, and the result is a smoother gradation of intensity near the shadow boundary. The basic pseudocode for a 25-sample implementation of PCF is:

float pcf_step_size = 256;

for (int j=-2; j<=2; j++) {

for (int k=-2; k<=2; k++) {

vec2 offset = vec2(j,k) / pcf_step_size;

// sample shadow map at shadow_uv + offset

// and test if the surface is in shadow according to this sample

}

}

// record the fraction (out of 25) of shadow tests that are in shadow

// and attenuate illumination accordingly

Notice that changing the parameter pcf_step_size governs how far apart your samples are, and thus has the effect of controlling the blurriness of the shadows. Here is an example (from-above) of rendering with pleasing smooth shadows.

You've done it! You've now written a few key parts of a real time renderer! Press d and enjoy the dancing lights and beautiful shadows!

Shadow Debugging Tips

The shadow visualizer (trigged by v) is a handy debugging channel. You can modify the shaders shadow_viz.vert and shadow_viz.frag as well as shadow_pass.vert and shadow_pass.frag to compute and present information you want to visualize during debugging.

For example, while we only use the depth information for the shadow pass render, we still create an additional color texture array shadowColorTextureArrayId_ showing the actual rendered result from shadow_pass.vert/frag shaders.

For your convenience in the starter code we render world-space normal images during the shadow pass onto the color texture array, which you can visualize by uncommenting the relevant code in shadow_viz.frag.

You should be able to adapt this tooling for your own debugging needs.

Notice that the baseline points for the assignment total 92 points.

There are many ways to go farther in this assignment. Here are a few ideas... however note that the last two in the list below involve significantly more work than extra credits in past assignments, and they could even be reasonable challenges for final projects. Points will be awarded at the discretion of the professors and TAs for excellent, high-quality work (the total credits can go up to 105). You can also consider some of these extensions as a final project.

-

Implement other BRDFs that are interesting to you. Google terms like "physically based shading".

-

Consider adding more sophisticated light types such as area lights via linear transformed cosines.

-

Consider implementing environment mapping where you render a cube map in a first pass and then use it as an input texture in the second pass to render reflections.

-

Improve the shadow mapping algorithm with cascaded shadow maps.