FINAL REPORT

Optimization and Parallelization of Image Stitching

Image stitching is the process of combining one or more overlapping images into the end result of one seamless panoramic picture. Our aim was to analyse and try to improve the performance of different stages of the image stiching pipeline. We obtained a 1.5x speedup in the total execution time of the stiching algorithm using SIFT descriptors. We also explored the usage of optimized rotational invariant BRIEF descriptors for the feature descriptor computation, which were seen to be an order of magnitude faster than the optimized SIFT descriptors.

Background

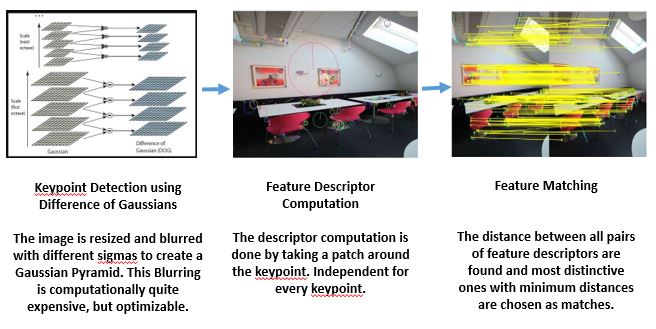

The image stitching pipeline can be broken up into 2 major chunks :

(a) Keypoint Detection and Feature Descriptors

(b) Homography and Blending

The baseline code for our implementation was OpenPano, an open-source image stitching code in C++ (coded by a CMU student who has taken 15418 in the past, therefore the code was well-written and already had all basic optimizations in place. It has omp pragmas for using mutiple cores as well).

PART 1 - Keypoint Detection and Feature Descriptors

(A) GAUSSIAN BLURRING :

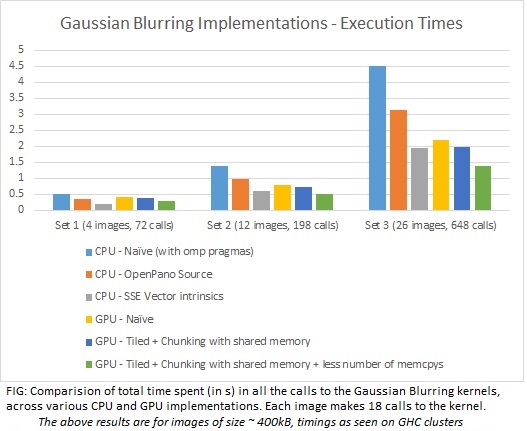

The blurring kernel is called multiple times for the DoG computation, and consumes a significant amount of execution time. Therefore, different implementations of the same were tried. All of mentioned implementations involved doing separable 1D convolutions instead of a 2-D convolution-

-

Naive CPU implementation : This is just the straightforward way with an imaged sized temporary array following a horizontal blur, which is then convolved with a vertical blurring kernel. This is clearly memory-bottlenecked, and was implemented just to see the improvement other implementations give.

-

OpenPano Implementation : The OpenPano implementation takes one row or column at a time, copies it into a temporary array and then applies the convolution on it before storing it into the result array itself. The memory storage overhead in this case is a just an array of max(height/width) of the input image. However, the number of memory loads and stores would still be high, because the entire result array is filled by the horizontal blur before moving onto the vertical blur.

-

Using SSE2 vector intrinsics with chunking : Here, the non-edge case pixels were convolved horizontally using SIMD instructions. However, SSE doesn't support gather instructions, so this could be done only for one of the 1D convolutions. Storing the intermediate temp array in column major order was tried (which would again allow a horizontal blur like load instruction). However, this was not helpful in improving the execution time.

-

Naive GPU implementation : This was just a CUDA version of the naive CPU version.

-

GPU Implementation : Using Tiling + Shared Memory Here, every block was responsible for a small patch of the input image.Every thread in the block would load a different pixel, and then compute the horizontal and vertical convolution on a pixel, with the intermediate temporary result array stored in the shared memory.

The two GPU implementations had execution times higher than the original implementation, so the code was profiled to see the time distribution between the CPU-GPU transfers and the actual kernel computation. In all the cases, nearly 75-80% of the time was involved in the memcpy (slightly bigger images were marginally better), thus making these GPU implementations unsuitable for images of the given size (around 400kB).

However, the feature detection involves computation multiple blurs of different scales on the same image. Thus, instead of copying the image to the device memory everytime, the same image is reused for all the different scale computations.

The timing comparisons between the different implementations can be seen below :

The SSE vector instrincs implementation is not as impressive as one would expect it to be. This is because the SIMD execution implemented in the kernel is limited to only one of the two 1-D convolutions involved, and there were additional divergent edge cases.

The GPU implementation with the intelligent memory transfers performs pretty well, and is close to, and mostly better than the CPU vector instrinsics version.

In the GPU implementations , it can be seen that the execution times improved as the number of calls to the kernel increased. Since there is no carrying of state between calls (in the first two implementations atleast), and the calls are not pipelines (which could have lead to some initial memory transfer latency hiding), this observation is rather puzzling.

(B) As seen from the GPU implementation of the blurring, the communication overhead is too much between the CPU and GPU. Thus, we chose to go with a SIMD calcution of the difference of Gaussian layers, which gave the expected 3.5-4x speedup in the DoG computation.

(C) FEATURE DESCIPTORS

There were 2 parallel approaches taken to the Feature Descriptors -

-

The SIFT computation in the OpenPano source code was fairly well-written. A few parallelizations (in the magnitude, orientation calculations) and minor optimizations/SIMD vectorizations (in the histogram calculation) were made, leading to a small improvement in the time required for computation for the descriptors. However, the optimization possible with SIFT is fairly limited (beyond multicore parallelizations).

-

Thus, a parallel approach taken to explore optimizing the feature descriptor calculation using BRIEF descriptors. BRIEF descriptors are binary descriptors, which are less compute intensive to compute and also to match.

SIFT descriptors are calculated by taking a weighted histogram of the orientations of the points in a patch around the keypoint, which need to be then matches using a Euclidean distance computation. BRIEF descriptors on the other hand are binary strings of intensity comparisons between sampled points in a patch around the keypoint, and are matched using a simple hamming distance computation. (xor and sum of the two strings)

The BRIEF descriptors were coded into the feature calculation algorithm, with vectorised version of Hamming distance calculation (using fast hardware popcount instructions). (Took care of reducing memory accesses and sampling point storage patterns that would lead to less cache misses)

- However, the problem is that BRIEF descriptors are not rotationally invariant. Adding rotational and scale invariance to them, without increasing the computation cost by much, was challenging but necessary to make this a reasonable alternative for SIFT. One way of doing that would be rotating the sub-patch in the image based on its orientation and then computing the descriptor around it. However, this is computationally very expensive.

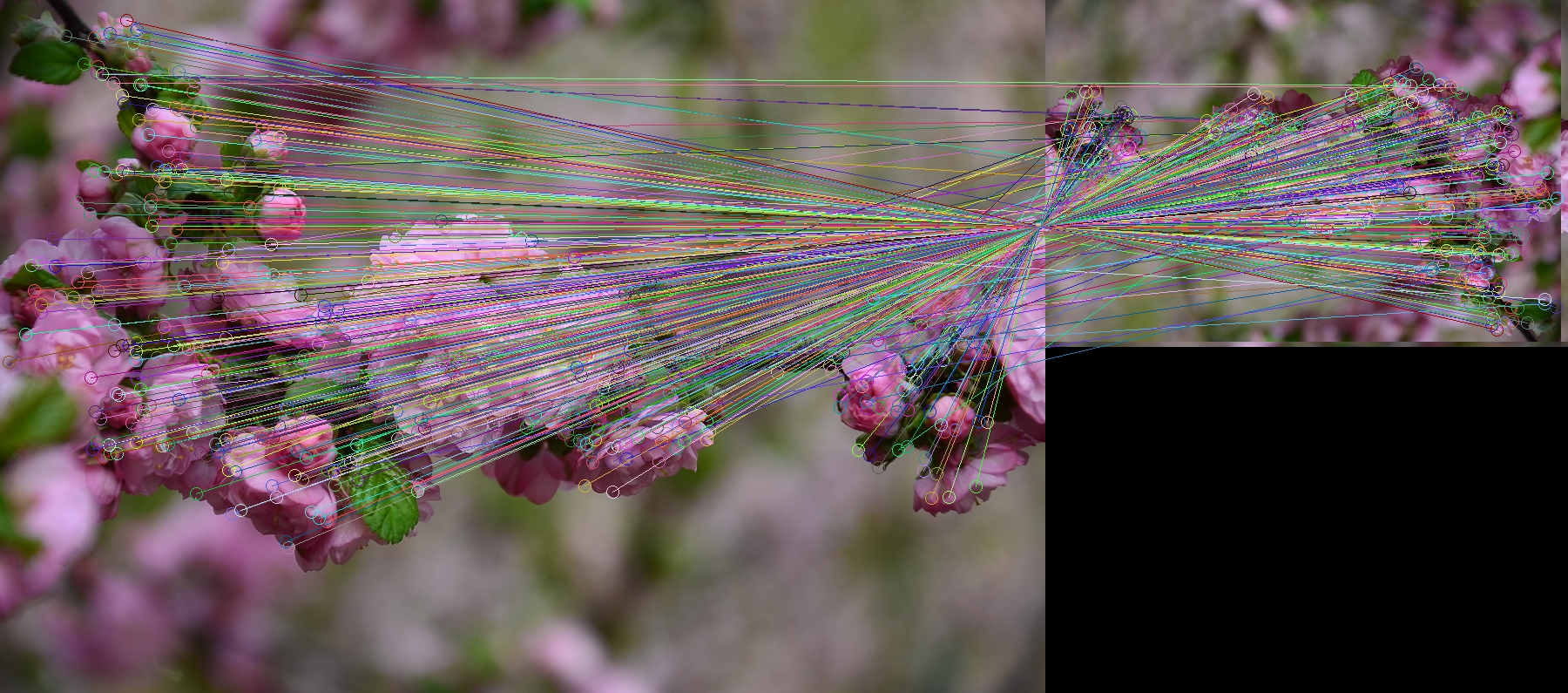

SOLUTION : To reduce the computational cost of adding rotational invariance, a set of sampling patterns for discrete angles of rotation were pre-computed. A simple spatially weighted mean was used to determine the orientation of a keypoint, and this orientation was used to choose the set of sampling points needed for the BRIEF descriptor computation (similar to what ORB does).

The figure belows shows the matches between an image and a rotated + scaled down version of it (therefore making the BRIEF descriptor scale and rotation invariant):

While the descriptors give good matches now, they still are not as stable as the SIFT descriptors, and don't give panoramas for some image sets. Further parameter tuning is required for the matching, as those parameters differ from the ones optimal for SIFT.

Results

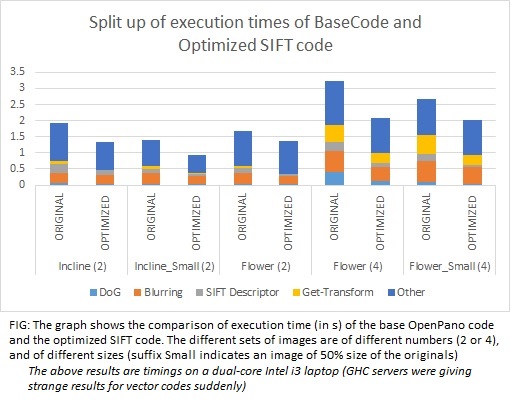

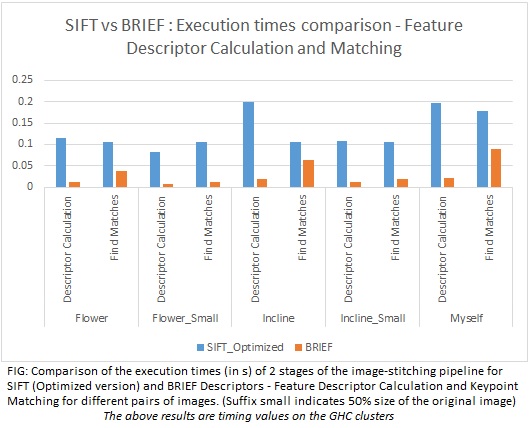

- Here's a brief overview of the timing breakup for the original SIFT implementation, optimized SIFT implementation and the BRIEF implementation for a pair of input images.

Base Code

Optimized code (with SIFT descriptors)

Modified code (with BRIEF descriptors)

- The optimization of the Gaussian Blurring and the DoG calculation along with the SIFT optimizations resulted in speedups of about 1.5x. The overall speedups remain relatively the same for different image sizes.

As the number of input images increase, there is an increase in the (i) Matching time - every image needs to be matched against every other image, and (ii) Blending time - since the output image is larger. Thus, these execution times become more significant that the time required for blurring and descriptor calculation, leading to decreased overall speedups. (Results for 36 input images not shown in the graph for clarity)

While this speedup may seem very small, it must be taken into consideration that (a) our baseline code was quite optimized (b) and more importantly, there are some parts of the pipeline that are intensive (orientation histogram computation for every keypoint, Blending) and/or sequential (RANSAC, Camera Estimation), limiting the total speedup of the panorama creation. The breakups shown in the graph below are the major portions where the optimizations have been done.

- Using BRIEF descriptors over SIFT gives 10x improvement in descriptor calculation, and 3.5-4x improvement in keypoint matching (which contribute about 15% to the total execution time). The results here are between different image pairs of 2 size ranges (multiple input images are still not stable enough for using BRIEF descriptors)

PART 2 - Homography and Blending

(A) BLENDING

At the final pipeline stage, various transformations are performed to the stitched image to preserve the geometry structure. The size of the image is now known. The next stage of correction is blending; to achieve seamless transformation from image to image. At the overlapping regions of the image, the algorithm calculates each pixel value based on some weights. The weight calculation is determined by the x-distance of the pixel from the centre.

- Scope for parallelization:

It was found that blending took up a significant amount of computation time in the image-stitching pipeline. Exploring the code for opportunities to parallelize, we found that: The updation of the each floating-point pixel value is governed by arithmetic operations. The same instruction stream is used across multiple data. Computation is performed across pixels, each of which is calculated independently, having no dependencies with other pixels. Due to available data-parallelism, it was decided that vectorization could be implemented to achieve speedup.

- OpenPano implementation:

The code was run on the GHC machines and already had significant amount of parallelization by exploiting multi-threaded execution across eight cores using OPenMP. While the iterations were performed in parallel, the data was being calculated at the rate of only one value per iteration.

- SIMD baseline implementation:

Using SSE2 vector instrinsics, four 32-bit floats are loaded at the same time, enabling the updation of four pixel values per iteration. Masking is implemented to perform appropriate computation to the pixel based on the conditional weights.

- SIMD optimized implementation:

SSE2 vector intrinsics are used again but SIMD branching is eliminated from the computations. This is done by exploiting the advantage that each pixel has three channel values that need to be updated, thus loading only these three floats into the four-lane vector. Since each vector corresponds to the same pixel, there is no divergence within the vector.

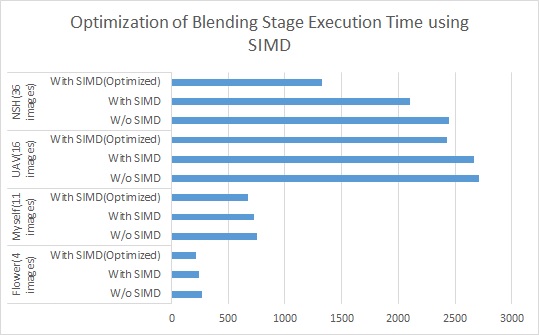

Results:

The SIMD baseline implementation achieved marginally better speedup than the original OpenPano implementation, if not the same performance. The SIMD optimized implementation fared much better with speedup ranging from 1.2x to 1.9x.

- Challenges:

Based on observations of the speedup , the following conclusions can be made: Due to the conditional nature of the computations involved, there is high divergence. This resulted in sub-optimal utilization of the vector lanes and peak performance was not achieved. This is the case when the unoptimized SIMD baseline code is used. Learning from the above, a more optimized version of SIMD implementation is used, which eliminates the obstacles to speedup caused before. Speedup is significantly more noticeable, but the lack of utilization of one out of the four lanes in the vector affects the performance to an extent. There are more operations to the blending, such as inverse transformation and bilinear interpolation with nearby pixels. Due to their sequential nature, they contribute to decrease in speedup.

Graph: The graph indicates the execution time in milliseconds of the various implementations of the blending stage as explained above. For a wider perspective, the blending is performed for image-stitching on a range of number of images and image sizes. All implementations were run on the CPUs of the GHC machine cluster (Intel Core i7 3.2 GHz 8-core processors).

(B) HOMOGRAPHY

As part of the homography matrix calculation, in the camera estimation mode when images have different focal lengths, rotation matrices of the connecting images are estimated from an initial rotation matrix and the homography. This is done by creating a pair-wise matching graph of images with weighted edges corresponding to matching confidence. Then, the estimation procedure follows a maximum spanning tree-like implementation. The goal was to parallelize the traversal of the graph. However, due to the usage of queue data structures, the parallel implementation with critical sections resulted in slower execution times.

Division of Work

-

Akanksha Periwal (aperiwal) : Gaussian Blurring Implementations, SIFT Optimization, BRIEF descriptor implementation, rotational invariance and optimization

-

Sai Harshini (snimmala) : Homography and Blending

CHECKPOINT UPDATE

Checkpoint Update

The initial plan was to work with the OpenCV implementation of the Stitcher Class as the baseline. However, on going through the code, we observed that that various stages of image stitching – feature detection, feature matching, homography estimation and blending – were not so distinctly seen in the code, and thus optimizing it would require a much deeper understanding of the code. A different baseline was thus needed and we decided to to go ahead with OpenPano. Although the Stitcher class of OpenCV was stated to be very slow, several recent optimizations have contributed to considerable speedup. The OpenPano implementation also has several optimizations incorporated, making it a faster algorithm than what was expected. This has made the problem of reducing execution time more challenging for us, requiring us to come up with more innovative and indirect ways of parallelizing the code.

WORK DONE:

Understanding the code and understanding the possible opportunities for further optimization.

The image stitching can be broadly divided into 2 parts :

-

Keypoint detection, Feature Description and Matching

- As mentioned above, the base code uses SIFT feature descriptors, which though more stable are also computationally intensive. There was a relatively naive implementation of BRIEF feature descriptors which wasn't completely incorporated into the code. However, looking at the simplicity in computing and comparing BRIEF desciptors (which uses just Hamming distance), we decided to explore using them instead of SIFT.

- A uniform distribution was chosen for the pattern generation, and the Hamming distance code was vectorized and sped up.

- DoG calculation was also vectorized.

- With these changes, the feature calculation time reduced by more than half when compared to SIFT descriptors.

- However, one key problem being faced now is the number of matches being found in case of these desciptors are much lesser compared to the previous case, making the feature matching time higher than in case of SIFT descriptors.

- The gaussian blurring, and extrema detection are areas that can still be optimized further.

-

Transform estimation, blending and stitching

- An area for potential optimization was found in the camera estimation mode when cameras with different focal lengths are used. After building a graph of pairwise matches of the images with matching confidence as weights, a maximum spanning tree is built to determine the best matches. Currently, a sequential algorithm is used to compute the tree. Thus, parallelization is being attempted to increase speedup.

PLAN AHEAD:

- Before 30th April:

- Optimize the gaussian blurring kernel – work on CPU

- Optimize extrema detection

- Complete parallel implementation of maximum spanning tree

- Before 5th April:

- Work on reducing the time required for finding the two nearest neighbours in the feature matches, and work around the problem of finding very less matches between some images (which affects the homography matrix estimation, inturn increasing the number of iterations required for RANSAC).

- Optimize various image processing calculations such as resizing, concatenation, cropping, transformation and color computations.

- Before 10th April:

- Explore possible parallelization of RANSAC

PROJECT PROPOSAL

Optimization and Parallelization of Image Stitching

We plan to optimize the image stitching pipeline that is used to create panoramas of several images through application of explicit parallelism directives such as those offered by Halide on a CPU.

Background

Image stitching is the process of combining one or more overlapping images into the end result of one seamless panoramic picture. There are several open source image stitching suites that are available for use. The image processing pipeline involved in this algorithm has scope for parallelization which we wish to exploit. The several stages in the image processing pipeline to perform the stitch are:

-

Keypoint Detection and Extraction: Extract salient points in an image that have distinctive features

-

Computing Feature Descriptors (SIFT/SURF/BRIEF): Characterize the extracted keypoints with a feature descriptor that helps describe the region around them and find correspondences between sets of images

-

Feature Matching: Calculating the similarity between the obtained feature descriptors and computing matching pairs using nearest neighbours found

-

Calculate Homography (using RANSAC): Find a 3x3 transformation matrix to compute how a planar scene would look from a second camera location given only the first camera image

-

Warping, Blending & Composition: Transform the images into a single frame and seamlessly blend them at the edges where they overlap

The Challenge

-

Homography calculation using RANSAC requires a large amount of iterative computation making it difficult to parallelize. It could become a bottleneck for the entire algorithm. There have been very few attempts previously to parallelize this computation.

-

In the case of high-resolution images, memory bandwidth could lead to a bottleneck.

-

Approaching the problem poses many parallelization constructs to choose from. Selecting the right combination of primitives for the different stages of the pipeline can be tricky and overwhelming.

Resources & Platform Choice

-

We plan to implement the algorithm on a single-CPU-multi-core platform. The required resources are available through the GHC machine clusters.

-

We will use the source code for the image stitching class from the openCV library as the reference code for our project. Check it out!. This code is written in C++, which works well with a lot of parallelization APIs and libraries. Python being an interpreted language would be much slower, making C++ a much better choice since we are concerned about performance more than ease of coding.

-

We plan to explore Halide to help us apply our image processing optimizations more rapidly. Further, Halide is embedded into C++, making our language choice effective.

Goals and Deliverables

-

To significantly improve execution time of image stitching compared to OpenPano

-

Determine execution time differences between different stages of our implementation compared to the baseline code

-

Study the impact of the stitcher on images with different resolutions