JavaScript is a client-side as well as server side scripting language that can be inserted into HTML pages and is understood by web browsers.It also lets us bring dynamic behavior to static html pages. JavaScript is also an Object based Programming language. The general-purpose core of the language has been embedded in Netscape, Internet Explorer, and other web browsers.

Following are the JavaScript Data types:

1. Undefined

2. Boolean

3. String

4. Symbol

5. Number

6. Object

undefined means a variable has been declared but has not yet been assigned a value.

On the other hand, null is an assignment value. It can be assigned to a variable as a representation of no value.

Also, undefined and null are two distinct types: undefined is a type itself (undefined) while datatype of null is an object.

Unassigned variables are initialized by JavaScript with a default value of undefined. JavaScript never sets a value to null. That must be done programmatically.

isNan function returns true if the argument is not a number otherwise it is false.

1. It is a lightweight, interpreted programming language.

2. It is designed for creating network-centric applications.

3. It is complementary to and integrated with Java.

4. It is an open and cross-platform scripting language.

Yes, JavaScript is a case sensitive language. The language keywords, variables, function names, and any other identifiers must always be typed with a consistent capitalization of letters.

Less server interaction − You can validate user input before sending the page off to the server. This saves server traffic, which means less load on your server.

Immediate feedback to the visitors − They don’t have to wait for a page reload to see if they have forgotten to enter something.

Increased interactivity − You can create interfaces that react when the user hovers over them with a mouse or activates them via the keyboard.

Richer interfaces − You can use JavaScript to include such items as drag-and-drop components and sliders to give a rich Interface to your site visitors.

JavaScript is faster. JavaScript is a client-side language and thus it does not need the assistance of the web server to execute. On the other hand, ASP is a server-side language and hence is always slower than JavaScript. Javascript now is also a server side language (nodejs).

Negative Infinity is a number in JavaScript which can be derived by dividing negative number by zero.

Breaking within a string statement can be done by the use of a backslash, '\', at the end of the first line

Eg: document.write("This is \a demo to show how to break a string using a backslash“);

Eg:

var a=1, b=2,

c=

a+b;

The above code is perfectly fine, though not advisable.

Javascript allows you to create objects by using following methods:

Using function as a class :

function createInstanceFromClass(prop1, prop2) {

this.prop1 = prop1;

this.prop2 = prop2;

this.logInfo = function () {

console.log(this.prop1, this.prop2);

}

}

var obj1 = new createInstanceFromClass(‘testProp1’,’testProp2’);

obj1.logInfo();

Using Object literals:

var obj1 = {

prop1 : “prop1”,

prop2 : “prop2”,

logInfo : function() {

console.log(prop1, prop2);

}

}

obj1.prop2 = “Updated prop2”;

obj1.logInfo();

Using Object.create ():

The Object.create() method creates a new object, using an existing object as the prototype of the newly created object.

Eg :

var obj1 = Object.create({})

var obj2 = Object.create(obj1);

A function declaration is executed when it is invoked. Just like variable declarations must start with “var”,function declarations must begin with “function”

Eg:

function demoFunction() {

return true;

}

A function expression can be defined using an expression, it doesnt needs function name and is stored in a variable. They are always invoked with the variable name.

Eg:

var x = function (a, b) {return a * b};

Benefits of each of one:

Function declaration:

Eg: (you need to refer hoisting concept of javascript explained in Q.17 to understand this example)

alert(foo()); //Doesnt throws error. Alerts 5. Declarations are loaded before any code can run.

function foo() { return 5; }

Function expression:

1. Currying

2. Can be used as arguments to other functions

3. IIFE (Immediately invoked function expressions)

Scoping means determining where variables, functions and objects are accessible in your code.

Types:

1. Global

2. Local

Global:

A variable can be termed as global variable if its defined outside of a function. A global variable can be accessed from any other scope.

Local:

A variable can be termed as local variable if its defined inside a function. A local variable is accessed only within the function in which they are defined. This allows us to create variables that have the same name and can be used in different functions (also termed as variable shadowing).

Types of Local scope:

Block level:

When variable declared with var keyword within block level scope, it is accessible from the global scope, but is hoisted with undefined value.

Function level:

While, when variable declared with var keyword within the function scope, the variable has its scope limited to that function only.

In JavaScript, variables with the same name can be specified at multiple layers of nested scope. In such case, local variables gain priority over global variables. If you have a local variable and a global variable with the same name,the local variable will take precedence when you use it inside a function. This type of behavior is called Variable shadowing.

Eg:

function outer() {

var outerVar = 2;

function inner() {

var outerVar = 3; //inner function that can declare a variable with the same name because of its new scope.

return outerVar*2; // local variable gets accessed here so value is 6

}

}

Currying is a process in which we can transform a function with multiple arguments into a sequence of nesting functions,each taking a single argument. The number of nested functions depends on the number of arguments the curried function receives. Nested functions are closures.

Eg:

Normal function :

function mul(a, b, c) {

return a * b * c;

}

Usage : mul(1,2,3);

Curried function:

function mul(a) {

return (b) => {

return (c) => {

return a * b * c

}

}

}

Usage : mul(1)(2)(3);

Benefits of currying:

If you have a multi-parameter function, and you don’t receive all of the parameters needed to evaluate it in one place in the code, you can simply apply one or more parameters when you get them and pass the result to another piece of code that has more parameters and finish evaluating it there.

Eg: Multiple API responses used as different arguments in a curried function to accomplish a particular task.

A closure is an inner function that has access to the outer/enclosing function’s variables—scope chain. The closure has three scope chains:

1. It has access to its own scope (variables defined between its curly brackets)

2. It has access to the outer function’s variables

3. It has access to the global variables.

4. It has access to the outer function’s parameters.

Eg:

function outer() {

var outerVar = 2;

return function() {

return outerVar *2; // inner function that has access to outer function’s variables.

}

}

var closureConcept = outer();

console.log(closureConcept()); // returns 4

Hoisting in JavaScript is a feature in which the interpreter moves the function and variable declarations to the top of their containing scope before code execution.

During compile phase, all the function and variable declarations are added to the memory inside a javascript data structure called Lexical environment. So that they can be used even before they are actually declared in the source code.

A lexical environment is a data structure that holds the mapping of the name of the variable or function and its reference. (The reference would be actual object [including the function object] or primitive value).

Representation:

LexicalEnvironment = {

Identifier: <value>,

Identifier: <function object>

}

All declarations (function, var, let, const and class) are hoisted in JavaScript.

1. When var is hoisted, JS assigns an undefined value to it.

Eg:

console.log(a); // outputs 'undefined'

var a = 3;

2. When function is hoisted, JS assigns function reference to it.

Eg:

helloWorld(); // prints 'Hello World!' to the console

function helloWorld() {

console.log('Hello World!');

}

NOTE: The lexical environment object looks like this for the above cases:

lexicalEnvironment = {

a: undefined,

helloWorld: <helloWorld object>,

}

3. When let, const and class are hoisted, JS doesn’t assigns any value to it, it will assign undefined only when the JS engine encounters the declaration or assignment code at runtime.

Eg:

1. let & const :

console.log(a , b); // ReferenceError: a, b is not defined

let a = 3;

const b = 2;

2. Class :

let ashwini = new Person(“Ashwini”); // ReferenceError: Person is not defined

console.log(ashwini);

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

NOTE: The lexical environment object looks like this for the above cases:

lexicalEnvironment = {

a: <uninitialized>,

b: <uninitialized>,

Person: <uninitialized>

}

4. Function expressions and class expressions are not hoisted.

Eg:

funcExp();

var funcExp = function() {

console.log(“This wont work it will give an error”)

};

Precedence:

1. Variable assignment takes precedence over function declaration

Eg:

var fun = 22;

function fun() { console.log(“func 2”)}

console.log(typeof fun) // number

2. Function declarations take precedence over variable declarations.

Eg:

var fun;

function fun() { console.log(“func 2”)}

console.log(typeof fun) // function

A time span between variable creation and its initialization where they can’t be accessed is Temporal Dead Zone. This means we can’t access the variable before the JS engine evaluates its value at the place it was declared in the source code. Temporal dead zone applies to class and variables declared with let, const keywords.

A higher-order function is a function that either *takes a function as one of its parameters or *returns another function.

Eg: Array.map method is one of the most common higher-order functions. Array.map method takes a function that will be executed on every item in the array. Then it returns a modified copy of the original array.

function map(array, func) {

let copy = [];

for(let index = 0; index<array.length; i++) {

let original = array[index];

let modified = func(original);

copy[index] = modified;

}

return copy;

}

1. stands for Immediately invoked function expressions.

2. starts with a function expression followed by a pair of parenthesis to immediately invoke it.

Different variation of IIFE - Eg:

1. “!” symbol turns the following function into an expression

!function() {

alert("Hello”);

}();

2. Parenthesis inside the expression.

(function() {

alert("IIFE”);

}());

3. Outside Parenthesis

(function() {

alert("IIFE”);

})();

4. IIFE with return values

var result = (function() {

return "IIFE";

}());

5. IIFE with parameters

(function IIFE(msg, times) {

for (var i = 1; i <= times; i++) {

console.log(msg);

}

}("Hello!", 5));

Execution context literally refers to scope.

For eg:

var globalVar = 5; //global execution context

function firstName(param1) { // firstName method’s execution context

var firstName1;

var demoVariable = ‘demoValue’;

function firstNameFunction() {

this.firstName1 = param1;

}

function secondName(param2) { // secondName method’s execution context

var secondName1;

function secondNameFunction() {}

function thirdName(param3) { //thirdName method’s execution context

var thirdName1;

function thirdNameFunction() {}

}

}

}

firstName(‘Ashwini’)

The JavaScript interpreter in a browser is implemented as a single thread. When a browser first loads your script, it enters the global execution context by default.

With the above example, the execution flow of code enters the global execution context, when it encounters firstName method, it enters the firstName method and creates a new execution context which is specific and local to firstName method which we have termed as firstName method’s execution context. Similarly, a new execution context is being created, when the execution flow of code enters the secondName method and thirdName method.

The execution context object is depicted as follows:

executionContextObject = {

scopeChain: {} ,

variableObject: {},

this: {}

}.

Let’s consider execution context object for thirdName function:

executionContextObj = {

scopeChain: { VO + VO of secondName + VO of firstName + VO of globalContext},

VariableObject: { param3, thirdName1, thirdNameFunction },// function arguments + innerVariables + function declarations

this: {}

}

The execution context object gets created in 2 stages:

1. Creation stage - function is called but not executed

2. Activation stage - function is parsed and initialized with variable values.

The above example can be visualized in the two stages as follows:

Creation Stage:

executionContextObject = {

scopeChain: {….} ,

variableObject: {

arguments: {

0: ‘Ashwini’,

length: 1

},

param1: ‘Ashwini’,

secondName: pointer to function secondName(),

thirdName: pointer to function thirdName(),

firstName1: undefined,

demoVariable: undefined

},

this: {}

}

Activation Stage:

executionContextObject = {

scopeChain: {….} ,

variableObject: {

arguments: {

0: ‘Ashwini’,

length: 1

},

param1: ‘Ashwini’,

secondName: pointer to function secondName(),

thirdName: pointer to function thirdName(),

firstName1: ‘Ashwini’,

demoVariable: ‘demoValue’

},

this: {}

}.

Javascript is a single threaded language i.e the execution follows line by line sequence.

Before jumping to asynchronous javascript, let us understand synchronous javascript execution.

Synchronous Javascript execution:

var secondMethod = () => {

console.log(’Second method is called first’);

}

var firstMethod = () => {

console.log(‘First method is called first, but it is angry now’);

secondMethod();

console.log(‘lets not upset anyone anymore, End it!’);

}

firstMethod();

The above code will be executed sequentially and would result in the following output:

First method is called then, but it is angry now

Second method is called first

lets not upset anyone anymore, End it!

Asynchronous Javascript execution:

Asynchronous means - The code execution which is not executed in sequence. In other words a piece of code runs separately from the main application thread notifying the calling thread of its completion, failure or progress.

Now a question can come “How Javascript can be single threaded and asynchronous both?” The answer is that the asynchronous behavior used in the javascript code is not a part of JS language. They are built in the browser and accessed through the browser APIs.

Lets understand the architecture of the browser that has the main components involved in asynchronous javascript code execution:

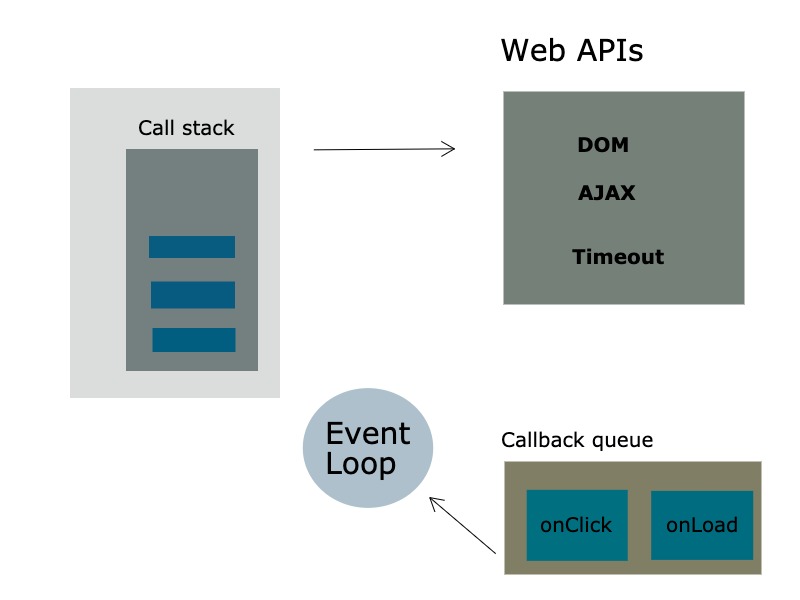

There are 4 main components involved here:

1. Call Stack

2. WebAPIs

3. Callback queue / message queue

4. Event loop

Call stack: All function calls will form a stack of frames

WebAPIs: The WebAPIs are built into your web browser. They are not part of the Javascript language itself, although they are built on top of the core Javascript language, which lets you to use them in your Javascript code.

Eg: Canvas API, Fetch API, Geolocation API, HTML Drag and Drop API, Service Workers API

Callback queue / message queue: The callback queue basically consists of all the callback functions in a queue.

Eg: The callback added in the setTimeout function will be placed in the callback queue.

Lets take an example to understand this better:

function mainMethod() {

console.log(‘Well Hello from the mainMethod! ’);

setTimeout(

function display() { console.log(’They are not gonna print me immediately!’)}

,0);

console.log(‘Now this ends here!’)

}

mainMethod();

Architecture of the browser:

Execution work flow:

1. Firstly, when mainMethod() is called, it is pushed to the callStack as the first frame.

2. The execution flow then adds the first statement to the call stack. i.e. console.log(‘Well Hello from the mainMethod! ’);

3. Once the message has been logged into the console, the execution flows moves to the next statement. In this case,it is setTimeout method. As the setTimeout method has 0 milliseconds to wait for, irrespective of the duration, the WebAPIs will start the timer that will wait for 0 milliseconds.

4. While the timer is running in the WebAPIs, the execution flow immediately moves to the next statement. i.e. console.log(‘Now this ends here!’)

5. Once the timer is completed running the duration mentioned in the setTimeout method, i.e. 0 milliseconds, the callback method is moved to the callback/ message queue, ready for execution. The execution order for queue is first in first out i.e. FIFO

6. Now, the Event loop comes into the picture here. The job of the Event loop is to look into the call stack and determine if the stack if empty or not. If the call stack is empty, it looks into the message queue to see if there’s any pending callback waiting to be executed. Therefore, the Event loop will check if any of the frame is present in the call stack, if yes, will wait till it gets executed, if no, will move the callback method from the callback queue to the call stack for execution.

7. The callback method is moved to call stack and is executed immediately. i.e. console.log(’They are not gona print me immediately!’)

8. Finally the output of the program is as follows:

Well Hello from the mainMethod!

Now this ends here!

They are not gonna print me immediately!

Asynchronous behavior can be achieved by the following methods:

1. callbacks

2. promises

3. async/await

Method overloading - when two different methods have the same name but have different parameters list.

Eg:

function add(n1, n2, n3 ) { return n1+ n2 + n3; }

function add(n1, n2) { return n1+ n2; }

Javascript doesn’t supports method overloading. If such two methods are defined one by one, then the latest method definition is picked up when add method is called. This is nothing but method overriding.

To summarize, Javascript supports method overriding and not method overloading.

‘this’ is an object whose value is determined by how a function is called.

To understand this concept more, let us re-visit the scopes concept. There are majorly two types of scope : Global and Local. Local can be block level or function level.

As for this topic, let us only consider Global and function scope.

Eg:

var first = ‘first’;

function demo() {

var first = ‘functionFirst’;

return this.first;

}

console.log(this.first); // first

console.log(demo()); // first

when demo() method is called, the global object is used as a context for the function call, therefore when the method refers to this, it points to the global object.

The global object already has defined first named variable with the value first and therefore demo() would return “first” as its value.

Now let us consider another example:

Eg:

var first = “first”;

var obj1 = {

first: ‘object 1 first’,

demo: function() {

var first = ‘functionFirst’;

return this.first;

}

}

console.log(this.first); //first

console.log(obj1.demo()); //object 1 first

Here, the “this” object in demo method will point to obj1 as obj1.demo() method was called. If there would have been another object obj2.demo(), the “this” object in demo method would point to obj2 context. No matter where the method is found: in an object or its prototype. In a method call, this is always the object before the dot.

Inheritance in javascript refers to the ability of reusing the behavior defined in one class into another class, without needing to redefine it.

For Eg:

An object has one method defined within it. Another object wants the same method to be able to access without needing it to redefine it in its own definition, to achieve this inheritance is used.

Inheritance in javascript is achieved using prototypes.

Before moving ahead, one important point to know is Everything in Javascript is an object. So if you define an entity using an object literal or function, it is an object eventually.

Prototype:

The prototype is an object that is associated with every functions and objects by default in javascript,where function’s prototype is accessible and modifiable and object’s prototype property is not visible.

Functions: Every function includes a prototype property that points to the prototype object of a base function or object (as ultimately everything in javascript is an object). The prototype object is an enumerable object to which additional properties can be attached to it, which will be shared across all the instances of its constructor function.

Objects: Every object includes proto property that points to prototype object of a function that created this object in the first place.

Now, Let us understand how inheritance can be achieved with object and with functions.

Objects:

var obj1 = {};

var obj2 = Object.create(obj1); //created instance of obj1 and assigned to obj2 i.e implementing inheritance.

console.log(obj2.__proto__); //outputs {} i.e. obj1

Objects will have __proto__ property that will refer to the inheriting object.

Objects will not have prototype property.

Functions:

function demo() {

return true;

}

var obj1 = new demo(); // implementing inheritance

console.log(obj1.prototype); // undefined

console.log(demo.prototype); // returns an object containing constructor property pointing to the actual method demo

console.log(demo === demo.prototype.constructor); // true, as demo method is the return value of demo.prototype.constructor.

Functions will have __proto__ property that would contain the native code.

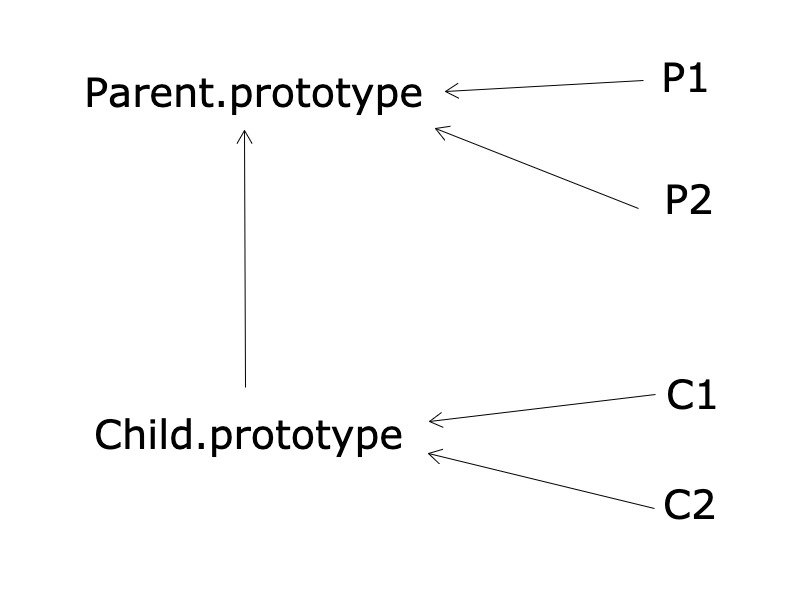

In Javascript, when we inherit an object, it does not copy the properties or behavior, it creates a link to the inherited properties or behavior. So whenever, the inherited properties are accessed, Javascript follows the links and returns the associated values. This behavior is called as prototypal inheritance in javascript.

In the above diagram, prototypal inheritance can be explained as follows:

1. Vehicle is the class from which Car class is inherited.

2. So, in programming terms, we can say that Vehicle is the base class and Car is the derived class.

3. There are two instances of Vehicle class - v1 and v2. So v1 and v2 will have all the properties accessible that are defined in the Vehicle class. But v1 and v2 wont have copies of the inherited properties, rather they would be pointing to the actual implementation of inherited properties of Vehicle class.

4. Similarly, c1 and c2 are instances of Car class. So c1 and c2 would be inheriting properties and behavior from Car, which in turn inherits properties and behavior from Vehicle.

For Eg: This method is also called as pseudoclassical pattern.

function Vehicle(vehicleCategory) {

var category;

this.category = vehicleCategory;

this.announceMe = function() {

return this.category;

}

return this;

}

function Car(carName) {

var name;

this.name = carName;

Vehicle.call(this,"SUV"); // Calling base class with call method, passing Car’s context (“this”) and assigning category value as SUV

this.announceMe = function() {

return this.name;

};

return this;

}

Car.prototype = Vehicle.prototype; // assigning prototype of Vehicle to Car

var v1 = new Vehicle("TVS"); // creating new instance of Vehicle, hence all properties defined in Vehicle will be accessible in v1 variable.

v1.announceMe(); // v1 instance able to access behavior of Vehicle

var c1 = new Car("XUV"); // creating new instance of Car, hence all properties defined in Car and also in Vehicle will be accessible in c1 variable. The reason behind this is Car’s prototype is pointed to Vehicle’s prototype. So the properties and behaviors defined in Vehicle prototype will be available to c1 instance.

c1.announceMe(); // prints XUV

console.log(c1.category); // prints SUV

But the above example has one flaw, if you try to manipulate the Car prototype, it also gets reflected in Vehicle prototype, because of the following line.

Car.prototype = Vehicle.prototype;

For Eg, you try to add new behavior to Car.prototype, it will also be added to Vehicle.prototype and be available to all the instances created from Vehicle, like v1.

To avoid this, you just have to replace the following code:

Car.prototype = Vehicle.prototype;

And add the following code :

Car.prototype = new Vehicle(“SUV”);

The refined code is as follows: This behavior is called as prototypal pattern.

function Vehicle(vehicleCategory) {

var category;

this.category = vehicleCategory;

this.announceMe = function() {

return this.category;

}

return this;

}

function Car(carName) {

var name;

this.name = carName;

//Vehicle.call(this,"SUV"); // Removing this code as the category initialization is done with the replaced code itself.

this.announceMe = function() {

return this.name;

};

return this;

}

Car.prototype = new Vehicle("SUV"); // This also initializes the category property of Vehicle class.

var v1 = new Vehicle("TVS");

v1.announceMe();

var c1 = new Car("XUV");

c1.announceMe();

console.log(c1.category); // SUV

The primitive types will be copied by value i.e. null, undefined, number, string, boolean.

The objects are copied by reference, i.e. object, array and function.

Primitive assignment:

For eg:

var a = 10;

var b = a;

a = 20;

console.log(b); // outputs 10 as the assignment was done by value

Non-primitive assignment:

For eg:

var a = { kiwi: 10 };

var b = a;

a.kiwi = 20;

console.log(b.kiwi) // outputs 20 as the assignment was done by reference.

A Promise is an object representing the eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous function. On the completion of asynchronous function, we can have our own callbacks to handle the fulfilled value or the reason of rejection.

A promise is creating using the following code:

new Promise(executor)

Here, we are creating a new instance of Promise and passing an executor function. The executor function is passed with arguments resolve and reject. Resolve is used to indicate the successful completion of the asynchronous function. On the other hand, reject is used to indicate that the asynchronous function execution failed.

Eg:

Let us understand how a promise is being created.

var promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

if(/*anything*/) { // if asynchronous function is successfully completed

resolve(‘response to be sent or a success message’)

}

else { // if asynchronous function throws an error

reject(Error(‘message’))

}

})

Now with the reference of above example, “promise” object is an instance of Promise, will contain a then method, that will contain successful or failure callbacks. This can be demonstrated like this:

promise.then(successCallback, failureCallback);

Eg:

var promiseObj = new Promise(function(){

var twistValue = true;

if(twistValue) {

resolve(twistValue)

} else {

reject(Error(‘An Error occurred’ + !twistValue))

}

})

promiseObj.then(function(response) {

console.log(“Successful response”, response);

},

function(err) {

console.log(“Errorfull response”, err)

});

Design patterns allows us to structure code in a proper way, so that it can be maintainable, readable and reusable

There are multiple design patterns but here we will be covering only 4 design patterns:

1. Constructor design pattern.

In classical object oriented language, a constructor is a special function in a class that will initialize an object with default values.

Although Javascript does not supports native classes, but it does support constructors with the “new” keyword. The function can be used as a constructor and the properties can be initialized with default values.

Eg:

function Vehicle(name, noOfWheels) {

this.name = name;

this.noOfWheels = noOfWheels;

}

// Instead of defining the isCar method in the function definition, we are associating it with the Vehicle’s prototype, this will share only one copy of isCar across all instances of Vehicle, i.e. bmw and activa.

Vehicle.prototype.isCar = function() {

console.log(this.noOfWheels === 4 ? “Yes”: “No”);

}

var bmw = new Vehicle(“bmw”,4);

var activa = new Vehicle(“activa”,2)

bmw.isCar(); // Yes

activa.isCar(); // No

2. Module pattern :

So before deep diving into Module pattern, we need to understand two concepts:

1. Closures.

2. Access modifiers.

A closure is a function with access to the parent scope, even after the parent function has been returned. They help us to mimic the behavior of access specifiers through scoping. Javascript does not support access modifiers.

To implement Module pattern, IIFE is used.

Eg:

var moduleDemo = (function(){

var privateArr = [1,2,3,4,5];

return {

addValue : function(value) {

privateArr.push(value);

console.log(privateArr)

},

removeValue: function(value) {

privateArr = privateArr.filter(function(val) {

return value!==val;

})

console.log(privateArr)

},

getValues: function() {

return privateArr;

}

}

})();

moduleDemo.addValue(6);

moduleDemo.removeValue(1);

moduleDemo.getValues();

console.log(moduleDemo.privateArr); // privateVar wont be accessible here as the IIFE is already returned here. Although the closures addValue, removeValue and getValues are still able to access the privateVar of IIFE.

Module pattern introduces the separation of private and public parts of an object.

3. Revealing module pattern:

Revealing module pattern is an improvement to the module pattern. The difference is the entire logic is written in the private scope of the module and simply expose the parts we want to be public by returning an anonymous object.

We can also create alias when mapping private members to their corresponding public members.

To implement Revealing module pattern, IIFE is used.

Eg:

var moduleDemo = (function(){

var privateArr = [1,2,3,4,5];

function addValue(value) {

privateArr.push(value);

console.log(privateArr)

}

function removeValue(value) {

privateArr = privateArr.filter(function(val) {

return value!==val;

})

console.log(privateArr)

}

function getValues() {

return privateArr;

}

return {

add: addValue,

remove: removeValue,

get: getValues

}

})();

moduleDemo.add(6);

moduleDemo.remove(1);

moduleDemo.get();

4. Singleton Pattern:

The Singleton pattern allows us create exactly one instance of a class. If the instance is already created, return the old one.

To implement Singleton pattern, IIFE is used.

Eg:

var singleton = (function(){

var config;

function initializeConfig(values) {

this.id = Math.random();

this.type = values.type || ‘Car’;

this.noOfWheels = values.noOfWheels || 4;

}

return {

getConfig: function(values) {

if(config === undefined) {

config = new initializeConfig(values);

}

return config;

}

}

})();

var instance1 = singleton.getConfig({ type: ’TwoWheeler’, noOfWheels: ‘2’});

console.log(instance1) // returns the instance with type TwoWheeler

var instance2 = singleton.getConfig({ type: ’FourWheeler’, noOfWheels: ‘4’});

console.log(instance1) // returns the instance with type TwoWheeler

Once the instance has been created, any attempt to create another instance of same class would result assigning the old instance to the new one.

Modules are small units of independent, reusable code that is desired to be used as building blocks in creating a JS application. Modules lets us define public and private members separately. To understand how modules can be implemented with ES6 syntax, refer the ES6 documentation.

Before ES6, modules can be defined with simple functions / IIFE:

Eg: Demonstrating modules with IIFE

var modulesDemo = (function(){

var privateArr = [];

function addValue(value) {

privateArr.push(value);

console.log(privateArr)

}

function removeValue(value) {

privateArr = privateArr.filter(function(val) {

return value!==val;

})

console.log(privateArr)

}

function getValues() {

return privateArr;

}

return {

add: addValue,

remove: removeValue,

get: getValues

}

})();

modulesDemo.add(6);

modulesDemo.remove(1);

modulesDemo.get();

Here, we cannot access the methods add, remove and get without modulesDemo variable. Also, once the IIFE is returned, only add, remove and get methods can be accessed, but the local variable privateArr cannot be accessed, which plays a role of private variable here.

DOM stands for Document object model. It is a standard defined by W3C. When a webpage is loaded, the browser creates a DOM of the page.The HTML DOM is constructed as a tree of objects(nodes). DOM tree can be accessed and manipulated with Javascript. The HTML DOM is a standard for how to get,change, add, or delete HTML elements.

DOM Tree nodes types:

1. Document - represents the HTML document.

2. Element - represents an HTML element.

3. Attribute - represents an HTML element’s attribute.

4. Text - represents text inside an HTML element.

5. Comment - represents an HTML comment.

BOM stands for Browser object model. There is no standard defined for BOM, so different browsers implement it in different ways.

BOM’s main task is to manage browser windows and enable communication between the windows.

Typically, a collection of browser objects is collectively known as the Browser Object Model. The important BOM objects are as:

1. Document - represents the HTML document in a specific window.

2. Location - contains information about the current URL the user is visiting.

3. History - contains the information about the URLs visited by the client.

4. Navigator - contains information about the client.

5. Screen - contains information about the client’s screen. (width, height, available width and height, etc)

6. Frames - contains information about all the iframe elements in the current window.

Events: Functionally speaking, when a user interacts with a webpage an event occurs. For eg: clicking on a search button, selecting a menu or typing into an input box of a form. All these interactions are considered as events. Javascript provides us ways to catch these events and add behavior to the application in response to these events.

Event flow: Event flow is the order in which the event is received on the web page. There are two types of event flow:

1. Top to bottom (Event capturing)

2. Bottom to top (Event bubbling)

Event Capturing: Event Capturing is the event starts from the top element to target element.

For Instance, if you click on an element (for instance button ), the click event of the window object will be fired first followed by the click event of the button.

The reason behind this is every element of HTML is the child of the window object and the event flow order moves from parent to child elements.

For Eg: You have elements structured as follows,

html > body > div > p > span

If every element has click event associated with it, and if span element is clicked, the click event of window object will be fired initially followed by html, body, div, p and then span element’s.

The modern browsers doesn’t supports event capturing by default. To enable it, we need to pass “true” as a parameter while adding an event listener as follows:

element.addEventListener(event, callback, true);

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<div id="parent">

<button id="child">Child</button>

</div>

<script>

var parent = document.getElementById(‘parent');

var child = document.getElementById('child');

parent.addEventListener('click', function(){

console.log("Parent is clicked first”);

},true); // true passed for event capturing

child.addEventListener('click', function(){

console.log("Child clicked second!”);

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

Event Bubbling: Event bubbling is the event starts from the target element to its parents, i.e. from bottom to top.

For Eg: You have elements structured as follows,

html > body > div > p > span

If every element has click event associated with it, and if span element is clicked, the click event of span element will be fired initially followed by p, div, body, html and then window object’s. The modern browsers supports event bubbling by default. So no specific code is needed to activate event bubbling.

Eg:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<div id="parent">

<button id="child">Child</button>

</div>

<script>

var parent = document.getElementById(‘parent');

var child = document.getElementById('child');

parent.addEventListener('click', function(){

console.log("Parent is clicked first”);

}); // no params passed for event bubbling

child.addEventListener('click', function(){

console.log("Child clicked second!”);

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

StopPropagation: It stops the event from bubbling to the parent elements.

Syntax:

event.stopPropagation();

StopImmediatePropagation: A single element may have multiple event handlers associated with it. So to prevent any of the event handlers to execute, stopImmediatePropagation is used.

Syntax:

event.stopImmediatePropagation();

Memoization is a programming technique which attempts to increase a function’s performance by caching its previously computed results. The parameters passed to the memoized function are used to index the cache array. So, if the same parameter is passed to the function, the cached value will be returned, else the result will be added to the cache.

Eg:

const memoizDemo = () => {

let cache = {};

return (value) => {

if (value in cache) {

console.log('Fetching from cache');

return cache[value]; // Here, cache.value cannot be used as property name starts with the number which is not valid JavaScript identifier. Hence, can only be accessed using the square bracket notation.

}

else {

console.log('Calculating result');

let result = value + 20;

cache[value] = result;

return result;

}

}

}

// returned function from memoizDemo

const addition = memoizDemo();

console.log(addition(20)); //output: 40 calculated

console.log(addition(20)); //output: 40 cached

concat() - Joins two or more arrays, returns a copy of joined arrays.

Eg:

var array1 = ["Cecilie", "Lone"];

var array2 = ["Emil", "Tobias", "Linus"];

var children = array1.concat(array2);

every() - checks if every element in an array pass a test. If it finds an array element which fails the test, every() returns false and stops execution else returns true

Eg:

var ages = [1,22,33,4,55];

var everyResult = ages.every( function( currentValue, index, arr) {

return currentValue < 60;

})

console.log(everyResult); // true

fill() - fills the elements in an array with a static value.

Eg:

var alphabets = [“a”,”b”,”c”,”d”,”e”];

alphabets.fill(“done!”);

console.log(alphabets); // [“done!”,“done!”,“done!”,“done!”,“done!”]

filter() - creates a new array with every element in an array that passes a test.

Eg:

var ages = [1,22,33,4,55];

var everyResult = ages.filter( function( currentValue, index, arr) {

return currentValue >=50;

})

console.log(everyResult); // [55]

find() - returns the value of the first element in an array that passes a test, else returns undefined.

Eg:

var ages = [1,22,33,4,55];

var everyResult = ages.filter( function( currentValue, index, arr) {

return currentValue >10;

})

console.log(everyResult); // 22

findIndex() - returns the index of the first element in an array that passes a test

Eg:

var ages = [1,22,33,4,55];

var everyResult = ages.filter( function( currentValue, index, arr) {

return currentValue >10;

})

console.log(everyResult); // 1

forEach() - calls a function once for each element in an array

Eg:

var ages = [1,22,33,4,55];

var everyResult = ages.forEach(function( currentValue, index, arr) {

currentValue = currentValue +10;

})

console.log(everyResult); // [10,32,43,14,65]

from() - creates an array from an object with length property or an iterable object.

Eg:

var a = Array.from(“abcdef”);

console.log(a); //[“a”,”b”,”c”,”d”,”e”,”f”];

includes() - determines whether an array contains a specified element, returns true if element is present else returns false.

Eg:

var fruits = [“orange”,”banana”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.includes(“banana”)); //true

indexOf() - searches an array for specified item and return its position, returns -1 if not found.

Eg:

var fruits = [“orange”,”banana”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.indexOf(“banana”)); //1

isArray() - determines whether an object is an array or not, returns boolean value accordingly.

Eg:

var fruits = [“orange”,”banana”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(Array.isArray(fruits)); //true

join() - returns the array as a string. The array elements are separated by comma, unless specified by another symbol.

Eg:

var fruits = [“orange”,”banana”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.join(“-”)); // orange-banana-apple-mango

keys() - returns an Array iterator object with the keys of an array.

Eg:

var fruits = [“orange”,”banana”,”apple”,”mango”];

var fruitsKeys = fruits.keys();

for(x of fruitsKeys) {

console.log(x);

}

map() - creates a new array with the results of a callback function for every element.

Eg:

var a = [4,9,16,25];

var x = a.map(Math.sqrt);

console.log(x); //2,3,4,5

pop() - removes the last element of an array and returns the removed element.

Eg:

var fruits = [“banana”,”orange”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.pop()); // mango

push() - adds new items to the end of an array and returns the new length.

Eg:

var fruits = [“banana”,”orange”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.push(“kiwi”)); // 5

reduce() - reduces an array to a single value. It executes a provided function for each value of the array (from left to right) and the return value of the function is stored in an accumulator.

Eg:

var numbers = [20,10,30];

function providedFunc(acc,value) {

return acc + value;

}

console.log(numbers.reduce(providedFunc)); //60

reverse() - reverses the order of the elements in an array

Eg:

var fruits = [“banana”,”orange”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.reverse()); //[“mango”,”apple”,”orange”,”banana”]

shift() - removes the first item of an array, and returns the removed item.

Eg:

var fruits = [“banana”,”orange”,”apple”,”mango”];

console.log(fruits.shift()); // banana

slice() - returns the selected elements in an array as a new array object, selects the elements starting at the given start argument and ends at, but does not include the given end argument.

Eg:

var fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Lemon", "Apple", "Mango"];

console.log(fruits.slice(3, 4)); // Apple

sort() - sorts the items of an array. The sort order can be either alphabetic or numeric, or ascending/descending order. The sort function will produce incorrect results for numbers. For eg: 25 > 100 because 2 > 1 (if numbers are sorted as strings)

Eg:

var fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Lemon", "Apple", "Mango"];

console.log(fruits.sort()); //[“Apple”,”Banana”,”Lemon”,”Mango”,”Orange”];

splice() - adds/removes items to/from an array, and returns the removed item(s). Eg: var fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Mango"]; console.log(fruits.splice(2,0,”Lemon”,”Kiwi”)); //["Banana", "Orange", ”Lemon”,”Kiwi”,”Mango"]

unshift() - adds new items to the beginning of an array.

Eg:

var fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Mango"];

console.log(fruits.unshift(”Lemon”,”Kiwi”)); //[”Lemon”,”Kiwi”,"Banana", "Orange", "Mango”];

assign() - copies all enumerable own properties from one or more source objects to a target object.

Eg:

const target = { a: 1, b: 2};

const source = { b:4, c: 5};

const newObj = Object.assign(target, source); // {a:1,b:4,c:5}

create() - creates a new object, using an existing object as the prototype of the newly created object

Eg:

const obj1 = { name: ‘Ashwini’ };

const newObj = Object.create(obj1);

console.log(newObj.name); //Ashwini

defineProperty() - defines a new property directly on an object, or modifies an existing property on an object and returns the object.

Eg:

const object1 = {};

object1.defineProperty(object1, ‘prop1’, { value: 200, writable: true});

console.log(object1.value); // 200

entries() - returns an array of a given object’s own enumerable keys and their values in two separate arrays i.e. [keys, values] in the same order as provided by a for…in loop.

Eg:

const object1= {

a: ‘Something’,

b: 42

}

console.log(Object.entries(object1)); // [ [“a”,”b”], [“something”,42]]

freeze() - freezes an object and returns the same object. Freezing an object means (no existing property alteration, no new property addition, no prototype updation)

Eg:

const obj = {

prop: 22

};

Object.freeze(obj);

obj.prop = 21; // throws an error.

isFrozen() - determines if an object is frozen.

Eg:

const obj1 = { prop: 42 };

console.log(Object.isFrozen(obj1)); //false

Object.freeze(obj1);

console.log(Object.isFrozen(obj1)); //true

fromEntries() - transforms a list of key-value pairs into an object

Eg:

const entriesFromMap = new Map([

[“first”,”second”],

[“firstValue”,”secondValue”]

]);

const obj = Object.fromEntries(entriesFromMap);

console.log(obj); // {first: “firstValue”, second: “secondValue”}

getOwnPropertyNames() - returns an array of all properties (enumerable + non-enumerable except for symbol) of an object.

Eg:

const obj1 = { a:1, b:2, c:3};

console.log(obj1); // [“a”,”b”,”c”];

getOwnPropertySymbols() - returns an array of all symbol properties of an object.

Eg:

const obj1 = { kiwi: 102};

const a = Symbol(“a”);

obj1[a]= ‘localSymbol’;

console.log(object.getOwnPropertySymbols(obj1)); // [Symbol(a)]

getPrototypeOf() - returns the prototype of the given object.

Eg:

const prototype1 = {};

const obj1 = Object.create(prototype1);

console.log( Object.prototype(obj1) === prototype1); // true

is() - determines whether the two given values are same or not. The two given values can be one of the following:

1. both undefined

2. null

3. either true or false

4. strings

5. the same object (same reference to the object)

6. numbers including NaN.

Eg:

Object.is(“foo”, “foo”); //true

Object. is({a:1},{a:1}); //false as the two objects have different references.

isExtensible() - determines if the object is extensible or not( not sealed / not freezed)

Eg:

const obj = {};

console.log(object.isExtensible(obj)); //true

Object.freeze(obj);

console.log(object.isExtensible(obj)) //false

seal() - seals an object. (no new property addition, no prototype updation) Existing properties values can be updated.

Eg:

const obj = { kiwi: true};

Object.seal(obj);

obj.kiwi = false;

console.log(obj.kiwi); // false

isSealed() - determines if the object is sealed or not

Eg:

const obj = {a: 22};

console.log(Object.isSealed(obj)); //false

Object.seal(obj);

console.log(Object.isSealed(obj)); //true

keys() - returns an array of a object’s own enumerable property names.

Eg:

const obj = { a: 1 , b: 2, c: 3};

console.log(Object.keys(obj)); // [“a”,”b”,”c”];

preventExtension() - prevents new properties to be added to an object

Eg:

const obj = {};

Object.prevent.Extension(obj);

Object.defineProperty(obj1, 'property1', {

value: 42

}); //error - cannot define property property1, object is not extensible.

hasOwnProperty() - prevents a boolean indicating whether the given property is own property of the object( not an inherited one!)

Eg:

const obj1 = {};

obj1.property1 = “This is an own property”;

Although, since obj1 is an object, it inherits toString from Object class.

console.log(obj1.hasOwnProperty(“property1”)); //true

console.log(obj1.hasOwnProperty(“toString”)); //false

isPrototypeOf() - checks if an object exists in another object’s prototype chain

Eg:

function obj1() {};

var obj2 = new obj1()

console.log(obj2.prototype.isPrototypeOf(obj2)); //true

setPrototypeOf - sets the prototype of the specified object by either another object or null

Eg:

var demo = Object.setPrototype({},null);

console.log(demo); // {} no properties

toString() - returns the string representing the object

Eg:

var a = [1,2,3,4,5];

console.log(a.toString()); //“1,2,3,4,5”

values() - returns an array of object’s own enumerable property values.

Eg:

var a = {

kiwi: 1,

miwi: 2,

tiwi: 4

};

console.log(Object.values(a)); //[“kiwi”,”miwi”,”tiwi”]