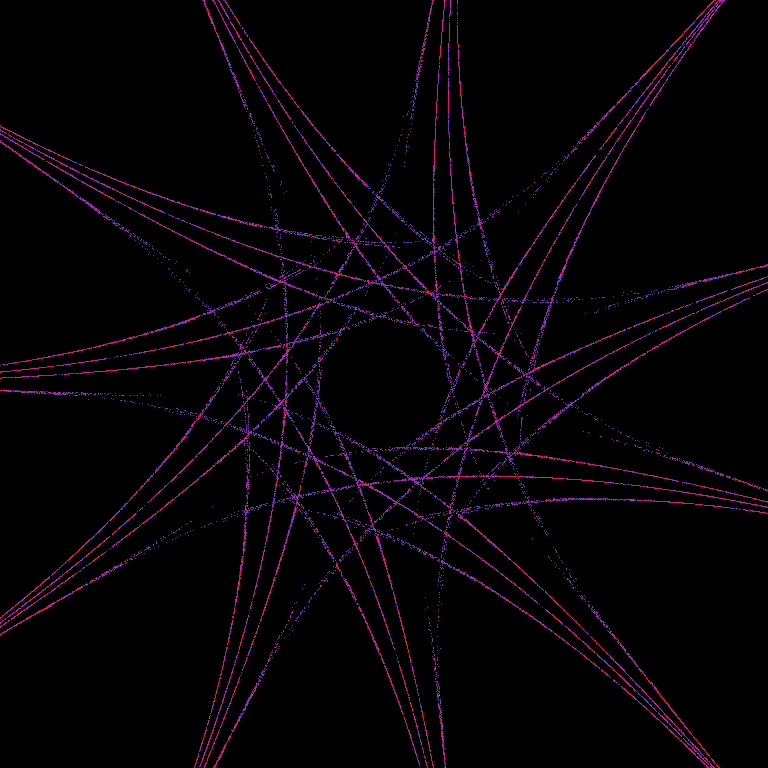

A Quil sketch implementing an IFS (Iterated Function System) fractal generator which enables you to create beautiful images by composing and iterating a bunch of functions over the xy-plane thousands of times and each time mapping the value obtained to the display window and colouring the resultant pixel.

LightTable - open core.clj and press Ctrl+Shift+Enter to evaluate the file.

Emacs - run cider, open core.clj and press C-c C-k to evaluate the file.

REPL - run (require 'fractagons.core)

or (use :reload 'fractagons.core).

Copyright © 2017 John Lynch

Distributed under the Eclipse Public License either version 1.0 or whatever. Basically it's open-source but please credit me if you use my code or borrow my algorithms!

- Program: Fractagons, vsn 1.01

- Author: John Lynch

- Date: October 2017

- Use: IFS fractal image generator.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ USER AND DEVELOPER GUIDE ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fractagons is an IFS (Iterated Function System) fractal generator which enables you to make pretty colour pictures by composing and iterating a bunch of functions over the xy-plane thousands of times and each time mapping the value obtained to the display window and colouring the resultant pixel according to criteria described (far) below.

The image appears slowly, pixel by pixel. It's like a colour version of watching an old-fashioned monochrome photographic print gradually manifest in the developing tray under the darkroom's red light!

If you want to skip all this information and just get started creating images, jump to the "Get started" section at the end of this user guide, or the ULTRA-QUICKSTART just below.

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon11V6-289269.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon12V30-52815.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon12V30-98467.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon48V9-250660.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon5V0-170226.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon5V0-260562.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon5V17-228338.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon5V36-201795.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon6V33-76924.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon7V38-106486.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon8V34-191056.png

https://github.com/1-0-2-4/fractagons/blob/master/examples/fgon9V25-450783.png

Fractagons is the lovechild of my romance with Clojure! It was a difficult relationship at first: she appeared inscrutable, cryptic, arcane. I wasn't convinced she needed to adorn herself with so many parentheses. Having had a long affair with Java, I felt lost without solid classes, interfaces and types. How on earth was I going to implement my 1000-lines-of-Java Complex number class (previously created to serve an escape-time fractal image generator I had been developing in Java1) in Clojure?

But people said, "You just need to understand her way of thinking!" I devoured "Clojure for the Brave and True", read and tried to understand Clojure code wherever I could find it, discovered Quil and played about in the Leiningen REPL. And ultimately I stopped resisting and gave myself to Clojure! At some point, the functional paradigm, immutable state, making "objects" out of simple maps and vectors, it just all started to make sense. It felt like a breath of fresh air! And from then on I have really been experiencing the joy of Clojure. It really is a lovely way to code once you take on board its mindset.

I would in fact go so far as to say that whereas writing nice, laconic, handsome, efficient Java code in order to solve some problem can give the same kind of satisfaction as solving the Guardian cryptic crosswword, doing the equivalent in Clojure feels... well, much more sensual!

Try this:

Fire up the program. You will see a Sierpinski Triangle begin to appear. Change the colouring algorithm by hitting "c". Hit "z" to clear the screen. Invert the colour by hitting "i".

Change from triangle to pentagon by hitting "N" twice. Scale up and down with "E" and "e". Reset the scale to default by typing Alt+S.

Keep hitting "z" to clear the display when you've tweaked parameter values - unless you want to create a composite image.

Go back to the Sierpinski Triangle by hitting "n" twice. Press "=" to invoke a pre-transform. Try changing the polygon order with "N" and "n" again.

Use "h" and "H" to play with the hue.

Hit "m" to mirror the image, "r" and "p" to reflect it, "o", "O" and "*" to rotate it.

See the guide above for details and for other tweaks.

Save your image with "s". Reload the last saved image with "R".

Recreate an image by reading in its corresponding "Fractagon Map" (.frm) file. Hit "_" to do this.

There are 12 Fractagon images in the examples directory, together with their .frm files. Try loading these and then tweaking them...

Hit "G" to get a random symmetrical fractal. If it's all black or you only see stuff developing around the edges, hit "e" a few times to reduce the scale. If you don't like the colours then use "c", "i", "h" and "H" to play with them. And "z" of course.

To make a composite image, change the pixel size to zero with "<" before tweaking parameters, then ">" to increase it to 1 again and recommence drawing.

Fractagons has been made possible by the wonderful Quil graphics library, developed and maintained by Nikita Beloglazov. Quil is kind of a Clojure wrapper around the Java-based Processing graphics system, so everything runs on a JVM, which is cool. And of course, as always with Clojure, the whole Java ecosystem is available should we require it. I have found it so much fun learning Clojure through Quil!

The basic algorithmic structure was inspired by Scott Draves' lucid and comprehensive description of the algorithm behind "Flame fractals" (http://flam3.com/flame.pdf), and indeed I have used a number of the non-parametric "variation functions" described therein. There are, however, several of significant differences. One is that I apply the variation function before the affine transform, and optionally after as well. The default variation is the identity function.

It may be noted that I have found it more than handy, indeed practically essential, to treat Cartesian points (x, y) as complex numbers x+iy, and here and there as 2D vectors from the origin.

Complex numbers belie their name, as working in the complex plane often simplifies matters considerably!

Note also that in transforming coordinates - performed by the fns (xy->display) and (display->xy) - I transform the origin between the top left corner (screen coords) and the centre of the viewing window (complex/xy plane) but keep the y-axis pointing downwards. Use the fn (reflectUD) to mimic the normal mathematical convention!

A further general point to note is that points (x, y) in the Cartesian plane are of zero size and uncountably infinite in number, whereas pixels on a screen are neither of these. This means that though a function's attrctor may be strange, values on different iterations may be close enough to be mapped to the same pixel. When this happens I don't want to lose the original colour, so the original colour and the newly calculated colour are "lerped", or merged/averaged.

I have introduced a few boolean flags, which control simple extra composed transformations of the (x, y) coordinates, e.g. swapping x and y, or treating (x,y) as (r, theta) which makes (x, y) -> (x cos y, x sin y).

A plethora of parameters may have their values tweaked by typing a key, so for example the parameter t is incremented by typing "T" and decremented by typing "t", and the "swap-xy" flag is toggled with a "?".

The Quil fun-mode update-draw loop enables me to pass around the program state, in the form of a map of keywords to integer, real or boolean values, from function to function. Changes are made to the state by typing a key which creates a new state with the appropriate parameter's value modified. In this documentation, flags/parameters of the state map are referred to by their keyword keys, with or without the leading colon.

The current state of the image may be saved at any time by hitting "s". It is saved as a .png file in a subdirectory of the current directory (where the program is run from) called "images/". If it doesn't exist it will be created. Along with the image we also save a short textfile containing the current state map, with the same filename but the extension .frm instead of .png. So, we can recreate an image (unless it's a composite: see below) by reading in the corresponding .frm file and assoc-ing it to the existing state map. How? Just hit the underscore key and a file-open dialog will pop up. Clojure makes object serialization so easy!

If you just want to revert to the last saved image, though, without its state, you can just hit "R".

To clear the canvas, hit "z". This will also reset the iteration count (:level) and print the state map.

To generate a random state and create its corresponding image, hit the g key - or G to guarantee symmetry.

Holding down Alt with g or G will also preserve the variation you have set.

To reset all parameters except :polygon-order, :variation and :pre-trans-index, type "Z".

To quit the program, type "Q". You won't be asked again!

POLYGON-J:

The main function used is an affine transformation I have devised. (polygon-j), based on the famous Sierpinski Triangle, but generalised to polygons of order n, where n>2.

The function takes seven parameters:

- z - a 2-element vector representing a complex number or a Cartesian vector -

the previous value of the function or pre-transform - t, u - real multiplicative parameters which can be varied with keys t, T, u, U default value for both: 0.5

- a, b - real additive parameters which can be varied with keys a, A, b, B default values: a = 0.75, b = 0.0

- n - an integer >= 3 which specifies the order of the polygon can be varied with keys n and N from 64 upwards N doubles, n halves.

- spoke - we multiply the intermediate result by a unit vector with angle corresponding to one of the spokes of the incipient polygon, e.g. for the default case n=3 we have angles 0, 2 PI/3, 4 PI/3. Chosen randomly by the caller.

- vfunc - the variation function (predominently trigonometrically-based) to be applied before, and optionally also after, the affine transform this itself a variation on Scott Draves' scheme. Increment/decrement the vfunc index (:variation state) with the # and ' keys.

If its parameters all have their default values, it will produce a Sierpinski Triangle.

Provided :reapply-vfunc is false, the random rotation by 2 PI / n ensures the image has rotational symmetry of order n.

PRE-TRANSFORMS:

A significant augmentation I have made in Fractagons is to provide the option of a pre-transform:

upon each iteration, the previous point is first shifted by the pre-transform this creates all sorts

of interesting possibilities, where a plethora of polygonal structures can arise.

Typically this fn is quite a simple trig fn, e.g. (x, y) -> (2 cos x, 2 sin y).

Pre-transforms are numbered 0 to (dec PRE-TRANS-FUNC-COUNT). Change the index with the k and K keys.

The (complex) output of the pre-transform may be further altered by squaring or square-rooting it. (use the / and . keys respectively for toggling these flags) and/or by squaring or square-rooting the real and imaginary components separately (use the # and ' keys). Toggling one of either pair sets the other to false.

VARIATIONS:

Currently there are around 40 of these. The selected one is applied before (polygon-j). Variation 0 (default) is the identity, equivalent to not applying any variation. Use the ! key, which toggles the value of (:reapply-vfunc state), to specify that the variation be also applied after (polygon-j).

SIZING:

The dots drawn are sized by default at one pixel, as the image will generally look crap with bigger dots.

However, this size may be decremented (to zero) or incremented (up to 8) by the < and >

keys respectively. This has two uses:

(a) When making a composite image, reduce to zero size by hitting < while changing parameters, so

as not to pollute the image with noise. Then use > to restart drawing.

(b) Increase to 2 or 3 pixel dots to see the general form and colouration of a new image quickly. When

these are satisfactory, just hit < or <<, then z, to restart with single-pixel dots.

COLOURS:

Colouration is either by speed or by curvature. The c key toggles this state. Control the hue offset with the h and H keys. Toggle hue inversion with the i key. I haven't devoted much energy to colouring and there's certainly scope for other, more sophisticated colouring algorithms.

MIRRORING:

The m key toggles the :mirror flag. Mirroring draws 4 copies of the image, reflected appropriately. Try it.

SCALING, SHIFTING:

Scaling and shifting the final image can be done with the x, X, y, Y, e and E keys. Whether they scale or shift the image is controlled by the (boolean) value of :scale-not-shift, toggled with the % key.

How much they scale is controlled by :param-delta: the scale is multiplied or divided by (inc (:param-delta state)). The default value of :param-delta is 0.2. The - and + keys are used to divide or multiply it by (sqrt 2). In the case of shifting, x decreases and X increases the x position on the screen (by 10 pixels), etc. e and E vary both coordinates together.

REFLECTING AND ROTATING:

| Key | Effect |

|---|---|

| r | Reflect image in y-axis. |

| p | Reflect image in x-axis. |

| O | Rotate image by PI/2. |

| o | Rotate image by PI/4. |

| * | Rotate image by half a sector, i.e. by PI/n, where n is the value of :polygon-order. |

INTEGER PARAMETERS:

Use n and N to vary the polygon order, v and V to change the variation fn, k and K to change the pre-transform.

REAL PARAMETERS:

The #{t, u, a, b, w} and #{T, U, A, B, W} sets of keys are used to decrement and increment respectively their corresponding parameters, in the case of t, u, a and b by dividing/multiplying by (inc (:param-delta state)), and in the case of w by subtracting/adding (* 2.5 (:param-delta state)), whose default value is 0.5.

Modifying the lowercase character with the Alt key instead negates the corresponding parameter. Modifying the uppercase character with the Alt key zeroes the corresponding parameter if non-zero, else resets it to default.

t, u, a and b are used in (polygon-j), w is not currently used.

TWEAKING:

| Key | Toggles |

|---|---|

| ? | Swap real and imaginary parts after pre-transform: x+iy -> y+ix. |

| P | "Polarise" z, i.e. treat [x y] as [r theta], meaning x+iy -> x cos y + ix sin y. |

| $ | "Polarise" the value of the variation function each time it's applied. |

| f | Apply the ballfold function. Tweak it with a and b parameters. [:deprecated] |

| ! | Reapply the variation fn after (polygon-j). This will probably result in an asymmetrical image. |

| . | Take the square root of the value of the pre-transform fn. |

| / | Square the value of the pre-transform fn. |

| ' | Take the square roots of real and imaginary components of the value of the pre-transform fn. |

| # | Square the real and imaginary components of the value of the pre-transform fn. |

| = | Invoke pre-transform. |

| % | Whether the x, X, y, Y, e and E keys control scaling (default) or shifting (by 12 pixels). |

MISCELLANEOUS COMMANDS:

| Key | Effect |

|---|---|

| Q | Quit the program |

| s | Save image and state map in ./images, which will be created if it doesn't exist. |

| R | Revert to last saved image (but don't alter current state). |

| _ | Load a new state from a saved state map, usually in a .frm file. |

| z | Clear the display, then carry on as normal. Use often when changing parameters to craft a nice image. |

| Z | Reset to initial state, except that the polygon-order, variation & pre-trans-index remain the same. |

| S | Reset the scale, x- and y- offsets, and cancel any mirroring. |

| D | Reset the a, b, t, u, w params to default. |

| j | Print the iteration count. |

| - | Decrement param-delta by dividing by (sqrt 2). |

| + | Increment param-delta by multiplying by (sqrt 2). |

| g | Create a random state, clear the display and go with the new state. |

| G | Create a symmetrical random state, clear the display and go with the new state. |

| Alt+g and Alt+G | As above but preserve the previously selected variation. |

| M | Trial feature: start/stop recording a sequentially-named image sequence |

We start (following the code below linearly) by defining various constants some, e.g. HALF-PI, are not currently used, but are retained for future convenience.

Then we have a load of utility fns, a few display functions and some miscellaneous stuff, of which one of the most important is (draw-dot). This fn is super. Give it a pixel and a size and it'll draw a dot for you, coloured with the current fill (q/current-fill), previously set in (update) by (q/fill).

The fns (setup), (set-default-params) and (init-state) cooperate to create the initial map of keywords to values which defines the program state. So, for instance, (:x state) returns the most recent value of x, (:polygon-order state) returns 3, 4, 5 etc. as you'd expect, and (:pre-transform state) returns a boolean specifyuing whether we're using a pre-transform or not.

There's also a rake of vector and complex utility fns, which we need to create interesting transformations.

Our variation fns come next. The first 20 are from flame.pdf (linked above) and for ease of cross-reference I have preserved Draves' numbering scheme. The last few are of my own devising. Thus we then need an array, or rather a vector, of these fn names so as to access them by index. I realise this is not the ideal scheme - lumping them all together under a (defmulti), might be better - but revamping this part of the program is not a priority at present.

After these, we find our core affine transform, (polygon-j), described above.

Following these, we see the (pre-transform) fn, referred to above, which actually encapsulates a bunch of function variants in a case statement. We pass it the index which is the value of (:pre-trans-index state) to specify which variant.

Lastly, the heart and associated organs: (update-state), (draw), (mouse-clicked) and (key-typed):

-

(update) takes the last (x, y) point, looks at the data in the state map to determine which fns to apply to it and what arguments to supply them with, applies them and spits out another point in the direction of...

-

(draw), which after determining what rotations, translations and scalings have been requested, calculates which pixel represents this new point, and then works out a colour for it: if (:colour-by-speed state) returns true (default) then the distance from the previous point determines the hue. If it's false, we want to choose the colour based on curvature, that means we're determining the colour as a fn of the difference of arguments of the vectors from the penultimate to the last point and from the last to the current point. Note that the state map holds a reference to the previous point and that (update) has already calculated the curvature for you. (draw) then calls (draw-dot) or (draw-dots) to actually colour pixels and complete the current iteration of the draw loop.

-

(mouse-clicked) just does a soft reset, blanking the display, resetting the iteration count and restarting with the point represented by the clicked pixel.

-

(key-typed) handles user input in the form of keys typed which change program state and therefore affect the image in some way (except a few like "j", which just prints the iteration count).

GET STARTED:

Run the program by firing up a Leiningen REPL in the root folder and evaluating

(use :reload 'fractagons.core)

This should compile both core.clj and dynamic.clj in the /src/fractagons directory, and kick off core.clj.

If you save changes in dynamic.clj then just eval (use :reload 'fractagons.dynamic).

All the action is in dynamic.clj: it’s a Quil “fun-mode” sketch, so it loops between the update and draw functions, passing a state map around as it does so (maintained behind the Quil scenes as an atom).

So it adds a pixel (or four, if mirroring) to the display window every frame and thus builds up the image.

You can control the image in many, many ways with keypresses (as long as the window has focus, of course).

Until I have written a comprehensive, non-alpha version of this quickstart guide you will have to refer to the documentation at the head of the program, reproduced in the README.md file for detailed info.

Upper-case letters increment the eponymous parameter. Lower-case letters decrement it

Real parameters change geometrically, integer parameters change arithmetically modulo something in unitary steps. Boolean values toggle.

Use Alt+upper-case to zeroise/reset-to-default a real parameter, Alt+upper-case to negate it.

It starts off by default producing a Sierpinski Triangle.

Try hitting “N” a few times to get a hexagon or whatever, “n” to go down.

Hit “=” to invoke a pre-transform, and “k” or “K” to choose the previous or next one

Change the variation function (the identity by default) with “v” and “V”.

Play about with colour using “c”, “i”, “h” and “H”.

Mirror the image with “m”.

Scale it smaller or larger with “e” and “E”.

Play about with the t, u, a and b parameters by hitting the corresponding keys. (Remember about zeroising and negating!)

Rotate the image by pi/2, pi/4 or half a sector (pi/n, where n is the order of the fractagon) using the keys “O”, “o”, and “*” respectively.

Reflect L-R or Up-Down with “r” and “p”. Change various other parameters with “$”, “P”, “f”, “’”, “#”, “.”, “/”, “!”, … (see reference above or look at the code in function (key-typed).

To save an image hit “s”. It will be saved in a subdirectory of the directory from which the program has been run, called /images. There will also be saved along with it a small text file containing the state map for that fractagon. If you want to recreate an image, just load its state map file, which has the same name as the image file except with a .frm extension instead of .png.

So how do you do that? Just hit the underscore key (“_”) and you will be presented with a file chooser. Select the file that is named as the image but with a .frm extension.

To clear the screen and start again hit “z”.

To reset all parameters except fractagon-order, pre-transform and variation, hit “Z”.

To reset scale and shift hit “S”.

To reset real params to default hit “D”.

To quit hit “Q”.

To get a random fractagon of whatever order you have set, hit “g”. If you want it to be symmetrical you’ll have to tun off “:reapply-vfunc” so hit “G” instead.

If you hold down Alt while doing this you’ll preserve the variation function you have set. This is good for exploring variants of a nice fractagon.

You can of course make composite images, by changing parameters but not hitting "z" to clear the screen.

This guide is far from complete so apologies in advance. I hope it’s enough to get you going!

Have fun.

John :)

1: I hope to be open-sourcing my Java escape-time fractal program on Github before the end of the year - but may re-implement it in Clojure first!

-

If I run Fractagons for many hours on my laptop it tends to crash with a

java.lang.ClassCastException: sun.awt.image.BufImgSurfaceData cannot be cast to sun.java2d.xr.XRSurfaceData. I have ignored this problem so far. -

Occasionally there is an Exception in the draw fn due to some function producing Infinity or NaN. I attempt to catch this by enclosing the entire code for the draw fn in a

tryblock and in thecatchblock decrementing the variation index. Sometimes this doesn't seem to work, though - an exception propagates and repeats - and I'm not sure why. Ideally I need to check out the variations where this sometimes occurs and calculate their ranges with the tweaks applied. Ideally they would all map points in the tetra-unit square to points in the tetra-unit square. If we take the sine or cosine of any real number, of course, we get a number in the range [-1, 1]. The same applies, of course, to sin2 and cos2. So for instance most of the pre-transforms constrain their output to the tetra-unit square by doubling the value of some function like this for both real and imaginary components. Note that a fn likeroot-costakes the square root of the absolute value of the argument, then gives it the sign of the original argument. This way we don't waste three-quarters of our range. The variation fns are not so well-behaved. I started off by just implementing some of Scott Draves' algorithms but didn't sit down and work out their ranges or anything. And the others are my inventions, fed more by untested creative ideas rather than careful analysis of the relation between function and image characteristics! If anyone would like to suggest a new variation or pre-transform, I'd be happy to try it out. We can add to them without breaking old fractal map files. And I wonder what's a better way to handle exceptions if the fns aren't guaranteed not to produce Infinity or NaN?