We attempted to abstract the task of tracking an object in a frame into two subtasks that could be implemented and tested independently: object detection, and tracking of the noisy readings from the object detection. Superclasses representing these subtasks are in tracking_interfaces.py.

In tracking_mocks.py are dummy implementations of each of the two interfaces, which allow testing the other without a function implementation of the one not being currently implemented. This helped us to work in parallel.

For debugging, tracking.py has a DEBUG flag that causes frames to be written to the debug_frames directory with highlights of the measured (from the ObjectDetector) and predicted (from the Tracker) bounding boxes of the object being tracked. There also exists a script called debug_video.sh that uses ffmpeg to stitch the frames outputted into this directory into a video file.

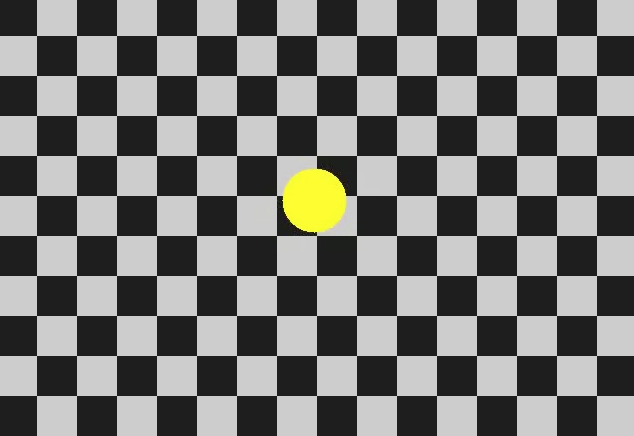

For the first ball tracking task, we just use a vanilla Hough Circles detector on a blurred grayscale version of the frame. Since the image is very simple, this naive approach actually works quite well. A NullTracker works fine here because there is little in the image to "distract" the Hough Circles detector or make its results poor.

For the second ball tracking task, we use the Hough Circles detector on the image that results from subtracting the current frame from the mean image of the previously seen frames. Then, to reduce noise from this, we use the AverageRadiusSmoother class, which keeps track of the average radius of the balls detected over the past few frames and converts the measured bounding boxes to have the same center but average radius. This prevents blips of much larger or much smaller radius, since the size of the ball does not change, only its position.

For the third ball tracking task, our approach has two passes. The first one visits every frame and computes a mean image (believed to be the background). Then, each frame is subtracted from this mean and the ball is detected using cv2.findContours. We found that on this particular test the HoughCircles detector didn't work well because the foreground object has the same color as the background and the region of the image that differs between the frame and the average is not strictly circular (thus we look at its bounding box).

Since this approach requires two passes, it does not use the genericTrack function used by other tests.

For the fourth ball tracking task, we use a similar approach to the HoughCirclesBallDetector from the first task with a few adjustments. The blur radius is a bit different. If the detected radius is very different from that last one, it is ignored and the previous radius is taken. There are a few problems with this that we could potentially fix if we had more time:

-

It relies on getting a good (near correct) radius from the first frame. If it's bad, everything afterward that's good will appear too different and be ignored.

-

It duplicates a lot of code from HoughCirclesBallDetector, which should have just been itself parameterized with the small changes we made to its behavior.

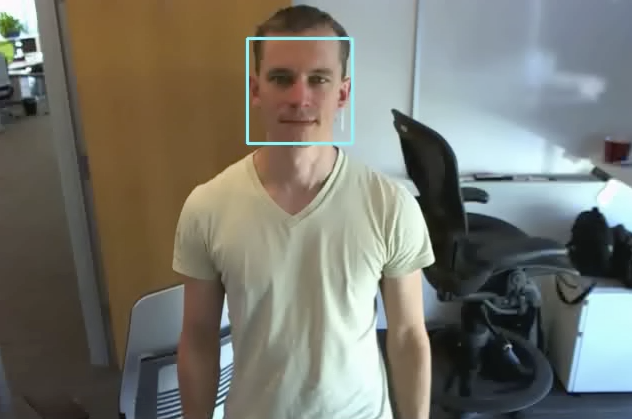

For the face tracking, we use the Haar-cascade Face Detection classifier built into OpenCV with a sample training dataset (haarcascade_frontalface_default.xml) we found online. It turns out the results from this are so good (i.e. not noisy) that using a NullTracker (one of our mock classes, which simply predicts the last thing that was measured, with no smoothing) works fine (and in fact the KalmanTracker's reluctance results in a poorer result).

Several of the things we tried that failed have been moved into tracking_attempts.py. Here's a brief explanation of each of them:

The first Tracker implementation we tried was a Kalman Filter, since we'd talked a bit about it in class, and one of us had used OpenCV's Kalman filter implementation in a previous outside project. We ran into a bit of difficulty using OpenCV's Kalman filter from Python because the cv2 bindings are incomplete. We had to use the old OpenCV 1 bindings (accessible through cv2.cv) to use the Kalman Filter.

Also, we ran into a problem where the Kalman filter was too reluctant to update its state when the direction of motion seen in the measurements changed radically. One approach we tried to alleviate this was suggested on StackOverflow, and was to slowly increase the process noise covariance parameter of the Kalman filter over time. This parameter represents the magnitude of stochastic noise expected in the model. We found this approach to help a bit, but not as much as we needed it to.

In the end, we ended up not using our KalmanTracker class for any of the 5 tracking tasks of the assignment.

This was a Tracker implementation intended to reject measurements whose center was too far from the centers of previously observed balls. It accomplishes this by computing Z scores over a small sample of measured ball locations.

The filterOutliers function is a second pass on the results list generated through genericTrack. After all frames have been processed through the normal ObjectDetector/Tracker pipeline, this function goes through the list of results and identifies individual frames that differ greatly from both the frame before and the frame after. When such frames are identified, their results are replaced by the result of the previous frame. There is a parameter indicating how much difference between frames is tolerated. We tried tuning this but didn't get great results in any case and ended up not using this approach.