A Befunge-93 Interpreter written in SQL.

This is a project for the SQL is a Programming Language Seminar during the winter semester 22/23 at the University of Tübingen.

This project implements an interpreter for the esoteric programming language Befunge-93—specifically, it implements the interpreter in SQL. The project also implements a Python-based frontend to enable easier interaction with the interpreter.

Befunge is a two-dimensional esoteric programming language invented in 1993 by Chris Pressey with the goal of being as difficult to compile as possible. Code is laid out on a two-dimensional grid of instructions, and execution can proceed in any direction of that grid.1

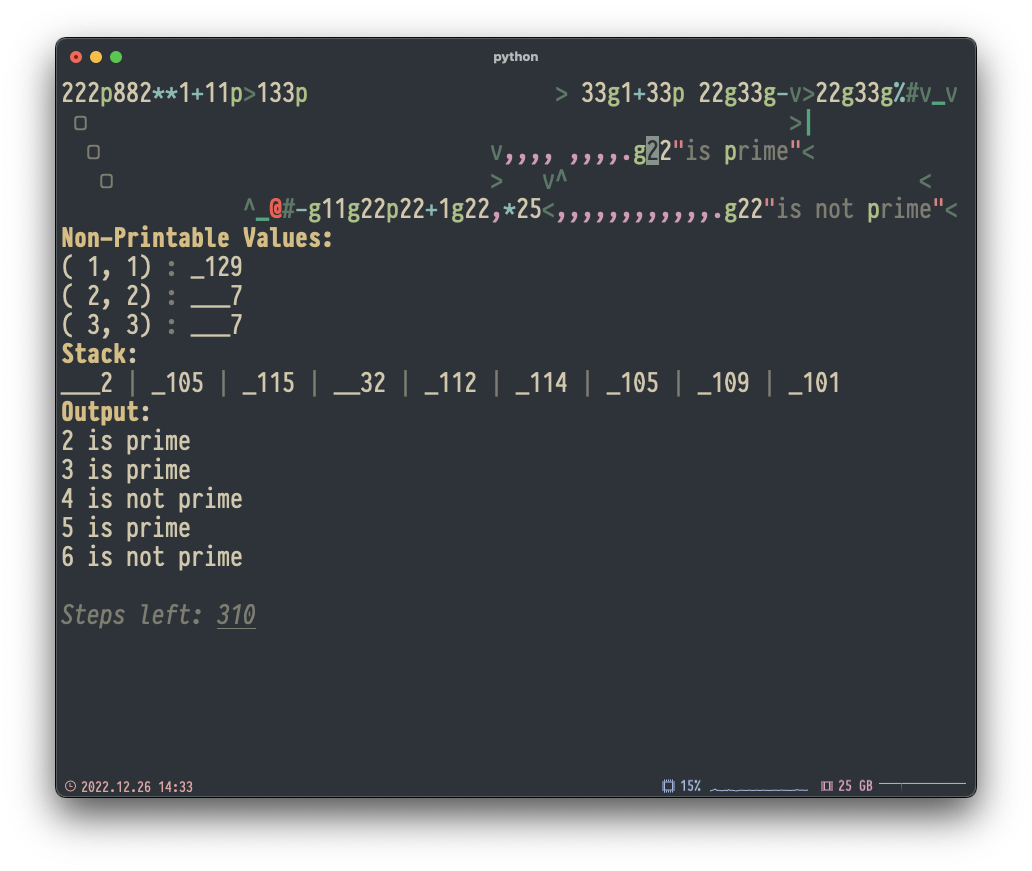

Example: Calculate Prime Numbers

222p882**1+11p>133p >33g1+33p 22g33g-v>22g33g%#v_v

o >|

2 v,,,,, ,,,.g22"is prime"<

1 > v ^ <

^_@#-g11g22p22+1g22,*25<,,,,,,,,,,,,.g22"is not prime"<

For the uninitiated: SQL is Turing complete since the introduction of recursive common table expressions (CTEs) in the SQL:1999 standard2. In theory, this enables you to implement any “reasonable” computation in SQL. However, you must express the computations control flow through a fixed-point combinator. The easiest way to achieve this is to transform a program into trampolined style3. I.e., a set of three functions init, step, and trampoline, where init produces some initial program state, step takes a program state and produces another, and trampoline represents the fixed-point combinator for the step function. In SQL, init and step correspond to the initial and recursive subqueries of recursive CTE, whereas trampoline, on the other hand, is already encoded in the semantics of recursive CTEs.

The Befunge interpreter implemented in this project uses such a recursive query to run Befunge programs. Obviously, this requires that the DBMS you run the interpreter on supports recursive CTEs. Aside from recursive CTEs, the DBMS also needs to support arrays, enums, Unicode strings, UDFs, and default arguments for UDFs. This interpreter is developed on PostgreSQL 154 and tested on older versions down to PostgreSQL 115.

The core of the interpreter is implemented in the UDF named befunge. The UDF takes a Befunge program as an input and produces a program trace. Befunge programs can usually interact with standard IO—i.e., can read from stdin and write to stdout. Since this isn't possible in SQL the stdin-content can be supplied to the befunge UDF via the inp parameter. Other parameters include the width and height of the program—limiting these can speedup programs that make use of edge-wrapping significantly.

Though the interpreter's output is relatively readable, using it is tricky. To make things easier, this project also includes a Python-based frontend, which also includes a stepper that visualizes the execution of Befunge programs better than any DBMS query result pager could. The frontend is implemented in Python 3.116 and uses Pipenv7 for dependency management. To use it, install those two, then run pipenv install to install the remainder of the dependencies, and finally, run pipenv run python befunge.py path/to/my/befunge/program.toml.

The input files—i.e., the path/to/my/befunge/program.toml from before—use TOML8 to encode all parameters the befunge UDF in the backend requires. In its simplest form, this only includes a program's source code but can also be enriched with the width and height fields described before. If your program takes user input, you must also add the input to the TOML file.

Footnotes

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hierarchical_and_recursive_queries_in_SQL ↩

-

Steven E. Ganz, Daniel P. Friedman, and Mitchell Wand. 1999. Trampolined style. SIGPLAN Not. 34, 9 (Sept. 1999), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/317765.317779 ↩