ESP8266-Gardena1251 - WLAN control unit for the Gardena 9V irrigation valve no. 1251

This project is a proof of concept applied to a practical purpose, especially regarding the following aspects:

- power consumption of the ESP8266 can be reduced to allow continuous operation over several months with a 2600 mAh battery

- real time keeping is possible without an RTC

- using a TCP client improves network security

- the single analog input of the ESP8266 can be used for simultaneously monitoring the supply voltage and measuring the valve and wiring resistance

The firmware is intended for an Espressif ESP8266 SoC to control the Gardena solenoid irrigation valve no. 1251 via WLAN. The management network protocol uses JSON for all telegrams.

** WARNING: **

Because this project is geared to be used with a latching solenoid irrigation valve, an inherent danger of flooding exists in case of control unit operation errors or misconfiguration. The valve is not intrinsically safe because it will not close by itself when power fails. On the other hand the WLAN control unit cannot "see" the true state of the valve and cannot take countermeasures in case of a discrepancy.

Therefore: ** Using this project is COMPLETELY AT YOUR OWN RISK! **

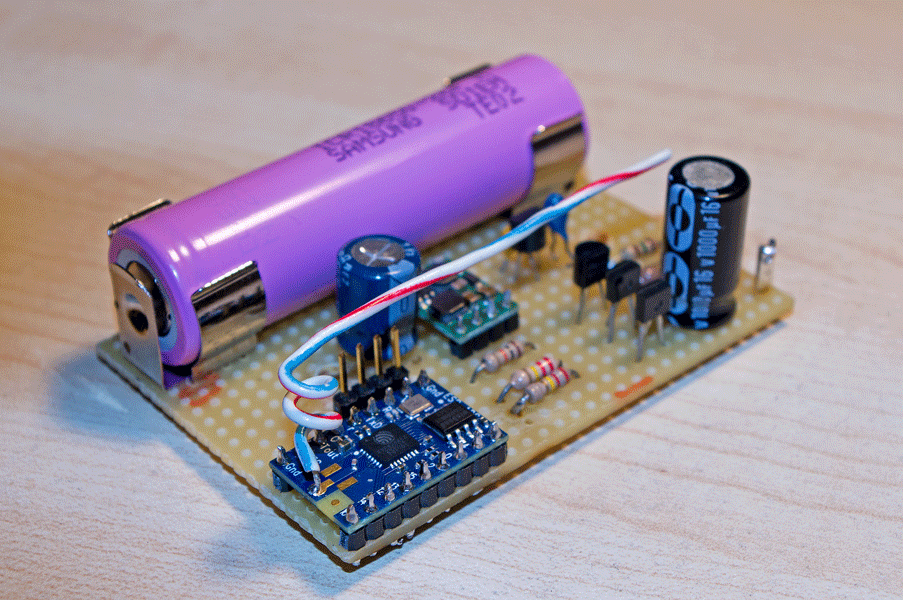

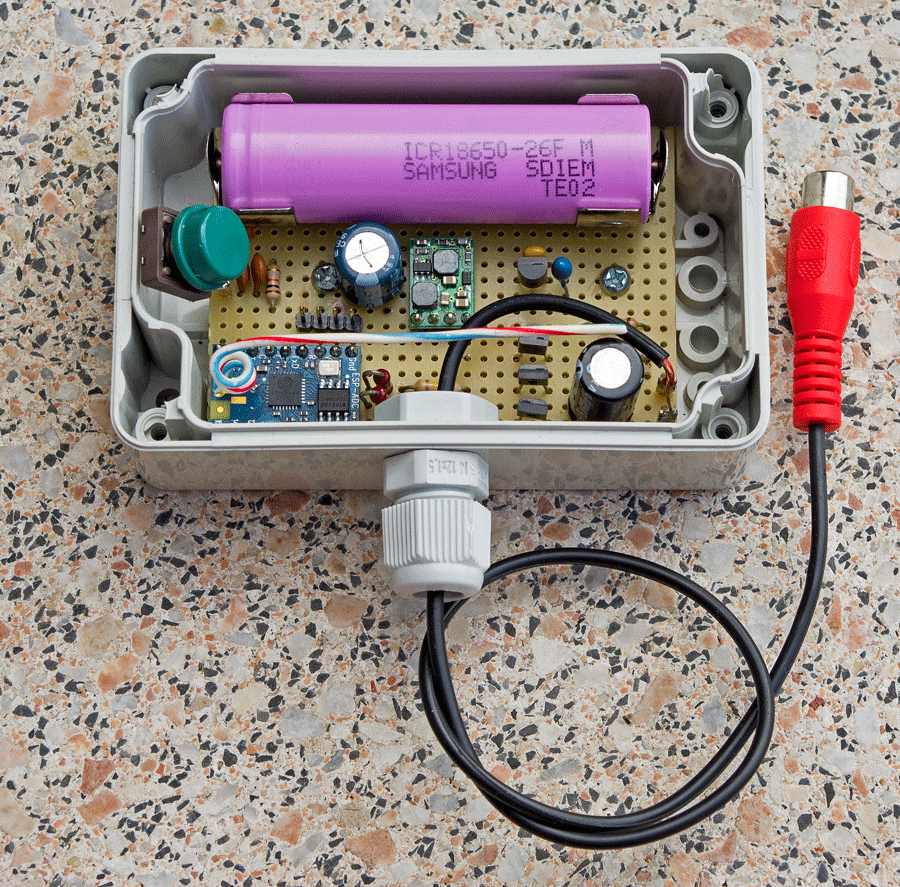

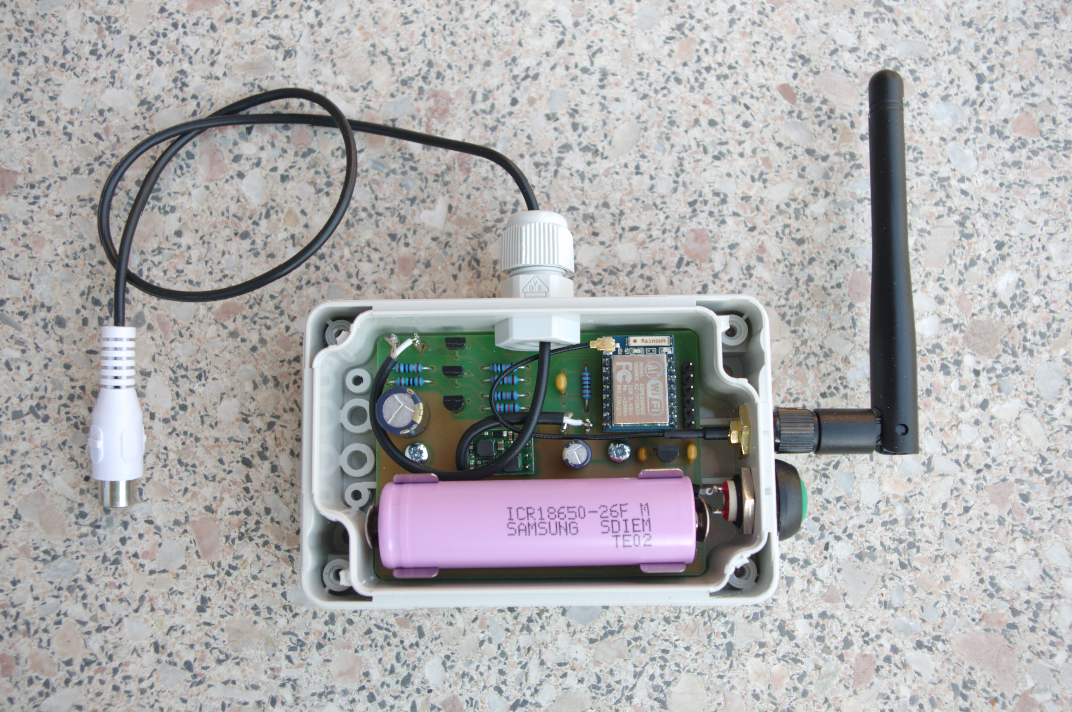

Hardware

To use this project as intended a specific control unit hardware including an ESP8266 SoC with waterproof casing is required. The material costs for the control unit are around 100 EUR and good electronic and mechanical skills are required for successfully manufacturing the control unit.

No reverse engineering was necessary for interfacing with the Gardena solenoid valve no. 1251 because the necessary facts have been published quite a while ago, e.g. in the Symcon forum in 2005. A discussion in the mikrocontroller.net forum from 2011 about solenoid drivers circuits using relays or bipolar transistors gave me the idea to use MOSFET transistors instead.

Firmware

Before deciding to design the firmware from scratch I considered using the NodeMCU Lua Firmware. The one reason that tipped the scales was the goal to maximize battery life as much as possible - and then every code line counts. The basics where already working about 2 weeks before Espressif Systems published the Low Power Voltage Measurement Project, but it was nice to be confirmed that the good old RTC CMOS RAM can still be used for the IoT.

Build Environment

The firmware was build using

- the Unofficial Development Kit for Espressif ESP8266

- with Eclipse Luna

- using the Espressif ESP8266 SDK 2.2.2

- and a Makefile based on the example in the book Kolban's Book on ESP8266

Special credits to Mikhail Grigorev for the seamless integration of the ESP8266 toolchain with Eclipse.

Configuration

Currently the WLAN access point configuration and the IP address and port of the management service must be set in the file user__config.h before building the firmware. In a future release this configuration will be done by WLAN without the need of changing the firmware. Also check if FLASHSIZE and FLASHPARMS in the Makefile matches the flash type of your ESP8266.

Management Service

By running a specifically tailored service in your network you can manage the operation of one or more WLAN control units. It is intentional that the WLAN control unit acts as TCP client and not as TCP server. This approach is slightly off in respect to many current IoT examples but hacking the WLAN control unit over the network will be a little bit more difficult this way.

An example implementation of a multi valve management service for the FHEM SmartHome Server can be found here.

Conclusions

This project is a proof of concept so there should be some results after about 6 months of development and testing and here they are:

-

The control unit can operate at least 3 months on a 18650 lithium-ion battery when using a WLAN wakeup cycle of 15 minutes. As expected, the theoretical value of about 12 months continuous operation was not reached. There are several reasons for this, e.g. a higher average consumption of the circuit in real life than on the breadboard and the self discharge of the battery. This result is still good in respect to the greediness of the ESP8266 but it is bought with the loss of just-in-time valve control.

-

The low battery detection/notification combined with a valve operation shutdown kicked in about a week before the battery was completely drained. To avoid damage to the battery in such a case, a full shutdown of the circuit is desired until the battery can be replaced.

-

Even when using the ESP8266's deep sleep mode that disables the RTC, real time keeping is still possible at reduced accuracy. The deep sleep timer of the ESP8255 has a tendency to wakeup about 3.75% earlier than should be expected. This deviation can be calibrated with some test runs and taken into account, yielding an acceptable absolute accuracy of a few minutes per day. Combining real time with a week timer, the control unit can operate without contact to the management service and a temporary WLAN link loss will not affect scheduled operations.

-

Employing a lambda/2 wire as antenna inside the control unit case and placing it a few centimetres below ground does not improve WLAN reception. This can be a reason for a higher battery drain because connecting to the management service takes longer or fails altogether. Using an external WLAN antenna with 6dBi gain and placing it a few centimetres above ground has improved the reliability of the WLAN link significantly. If this saves or cost battery life is hard to determine without measurement.

-

There is no suitable way for the control unit to detect the state of the solenoid valve. One way to make sure that the valve is closed when it should be would be to try to close it periodically every few seconds but this way of operation would drain the battery very quickly.

-

The overall reliability of the control unit proofed to be much better than expected. After initial adjustments to the solenoid driver circuit no loss of control was observed.

Longterm Results

Before starting this projects several alternatives were considered for the latching valve driver circuit:

- relay(s)

- H-bridge

- MOSFETs and a capacitor

The initial decision for the prototype fell on the 3rd variant using 3 MOSFETs and a 1 mF capacitor because this approach seemed to require the least amount of energy. While the concept proved to be true it seemed not to work reliably with different valves. The original Gardena valve control unit no. 1250 uses square pulses resulting in a constant current that a reasonably sized capacitor cannot provide - and some valves seemed to require the additional boost. Further increasing the capacitance is an option but it also increases the demands on the power supply and the required discharging times thus countering the energy saving aspects. To create the same pulses as the original Gardena valve control unit the 2nd hardware design uses a H-bridge. As it turned out, the true reason for the observed unreliability was caused by the RCA connector of the valve that did not connect properly. Using suitable pliers the diameter of the outer ring of the RCA attached to the valve can be slightly reduced to provide more contact tension. Both drivers variants are suitable for the valve with the capacitor driver using slightly less energy but requiring more PCB space (at least when using discrete components). The capacitor driver proves that the energy (pulse duration) used by the original Gardena valve control unit is much higher than typically necessary to operate the valve, especially the open duration.

The power requirements for the ESP8266 SoC could be reduced significantly by reducing the minimum runtime from about 1700 ms to about 500 ms when not operating the valve. This was possible by moving to the more recent Espressif ESP SDK 1.5.3. It is the combined effect of the removal of a workaround required for the earlier Espressif ESP SDK versions to avoid spurious high power draw in deep sleep (by disassociating from the AP before shutdown and reassociating after startup), event based AP connect detection and event based TCP connect/send/receive/disconnect detection.

After 3 years of operation the inner contact of the female RCA connector was completely corroded and had to be replaced. This was due to the low price of the component and the humid operation environment. Next to the waterproof case the connector must be of high quality to avoid this kind of maintenance.

In the 4th year of operation the RCA connector corrosion was the only real issue, while battery life has increased to more than 6 months, probably due to the modified WiFi handling introduced in the application after switching to Espressif ESP SDK 1.5.3. Covering the top of the valve with a watertight hood, like the original Gardena valve control unit does, helps to reduce the contact corrosion. Monitoring the valve and wiring resistance allows to detect pending failure. This requires an ADC input and both the relay driver and the H-bridge driver also need a shunt and an analog amplifier or a high resolution ADC to check the current to the valve. This disqualifies both driver types because it causes additional power consumption. With the capacitor driver it is enough to check the voltage of the capacitor. The ESP8266 has a suitable analog input but it is already in use for the supply voltage monitoring, so a 2-channel analog MUX is needed. Fortunately half of the MUX is already built into the ESP8266. It is enough to keep the voltage of the capacitor disconnected from TOUT when measuring the supply voltage VDD33 and this can be done with a another MOSFET that is directly controlled by GPIO 12. A single call of readvdd33() in user_init() for the supply voltage and an average of the output from system_adc_read_fast() for the voltage of the capacitor yield reproduceable results, the latter both with and without RF enabled. The same can be said about the resistance measurement with an absolute accuracy better than 10% at 40 ohm without calibration.

Licenses

Pictures, Schematic and Layout

Copyright (c) 2015 jnsbyr Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Firmware

Copyright (c) 2015 jnsbyr Apache 2.0 License

The firmware source code depends on:

Espressif ESP SDK 2.2.0

Copyright (c) 2015 <ESPRESSIF SYSTEMS (SHANGHAI) PTE LTD> ESPRESSIF MIT License

see LICENSE file of Espressif ESP SDK for more details