- Introduction

- MEGNet Framework

- Installation

- Usage

- Implementation details

- Datasets

- Computing requirements

- Known limitations

- References

This repository represents the efforts of the Materials Virtual Lab in developing graph networks for machine learning in materials science. It is a work in progress and the models we have developed thus far are only based on our best efforts. We welcome efforts by anyone to build and test models using our code and data, all of which are publicly available. Any comments or suggestions are also welcome (please post on the Github Issues page.)

A web app using our pre-trained MEGNet models for property prediction in crystals is available at http://megnet.crystals.ai.

The MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet) is an implementation of DeepMind's graph networks[1] for universal machine learning in materials science. We have demonstrated its success in achieving very low prediction errors in a broad array of properties in both molecules and crystals (see "Graph Networks as a Universal Machine Learning Framework for Molecules and Crystals"[2]).

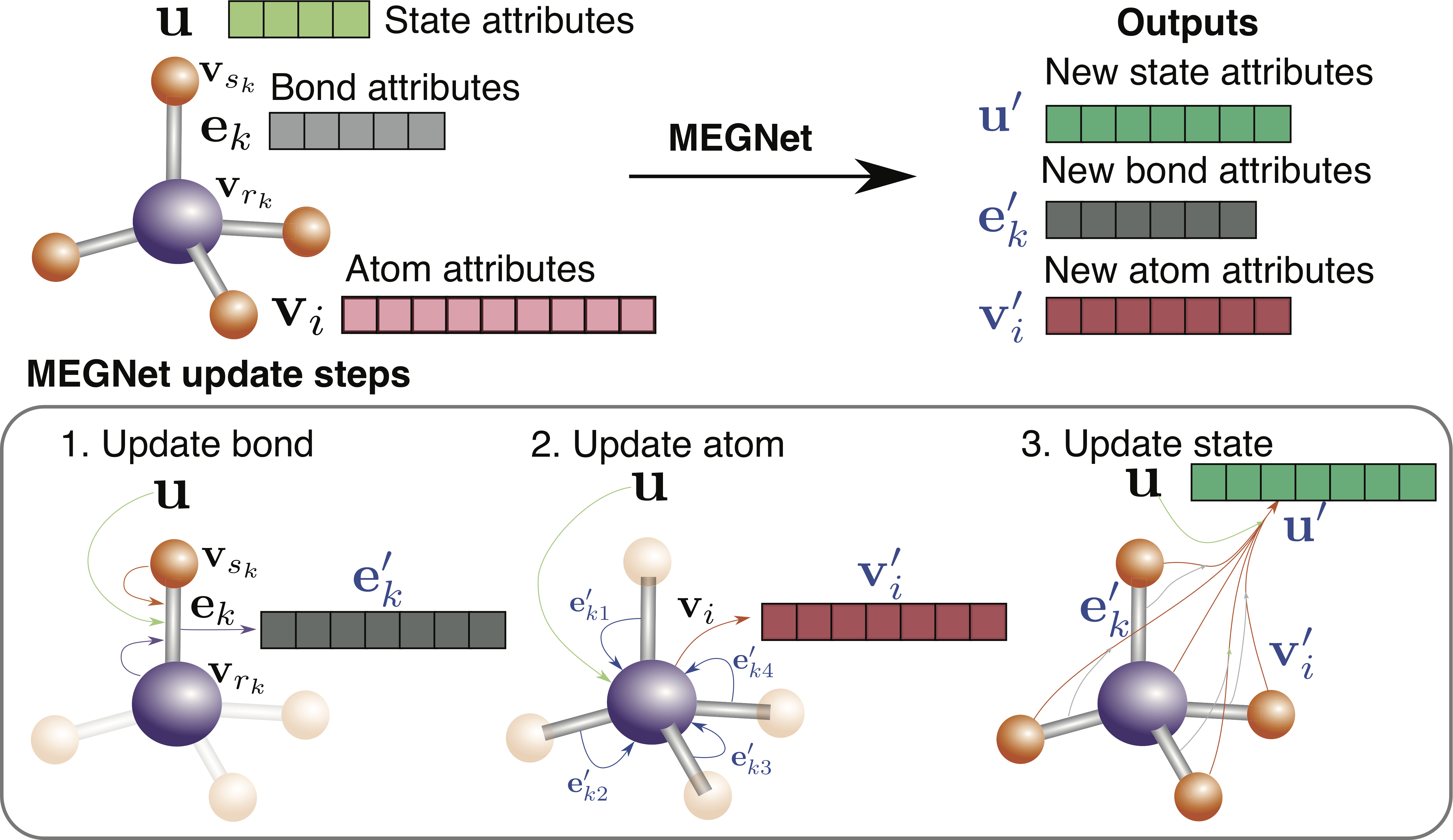

Briefly, Figure 1 shows the sequential update steps of the graph network, whereby bonds, atoms, and global state attributes are updated using information from each other, generating an output graph.

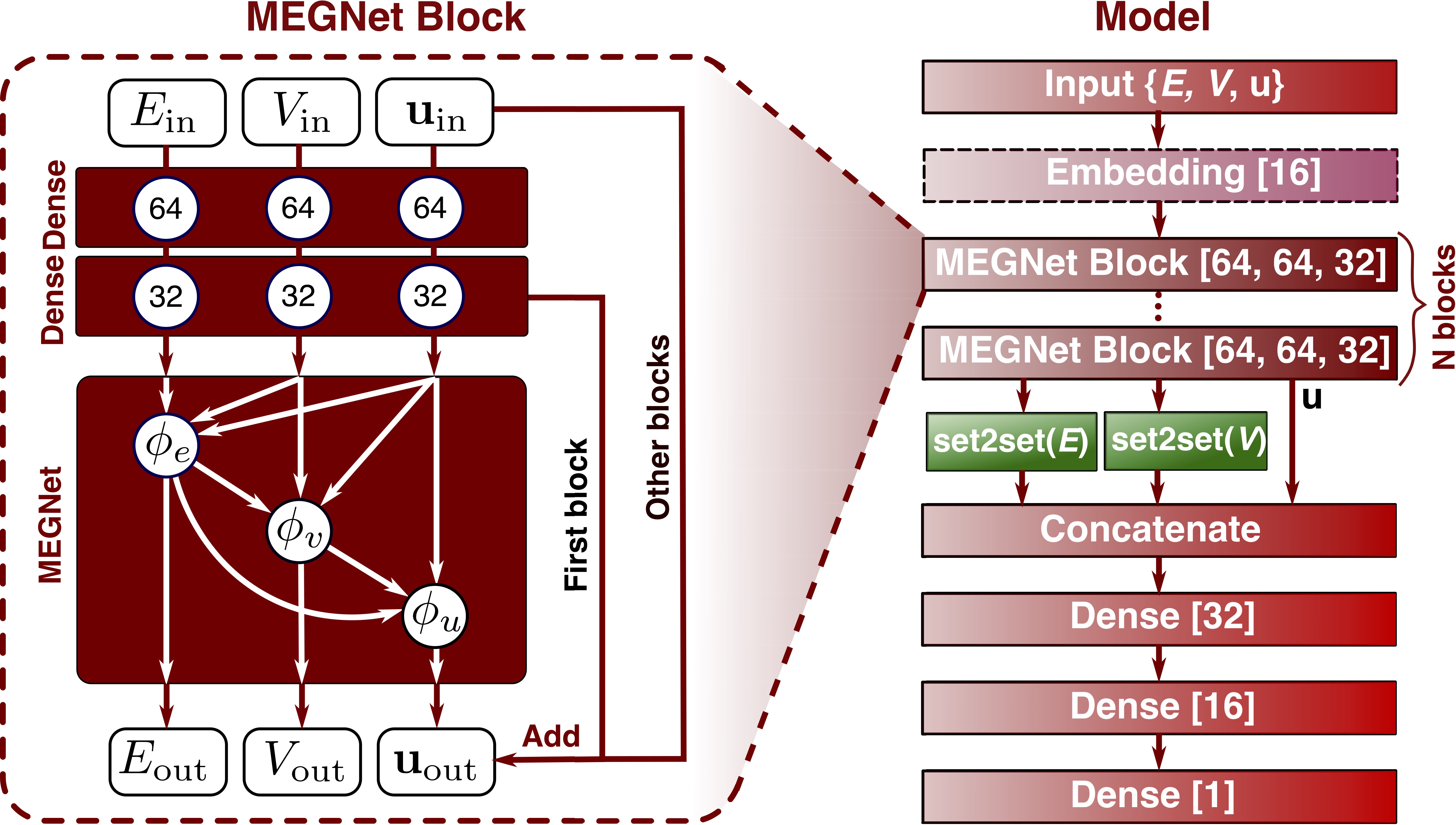

Figure 2 shows the overall schematic of the MEGNet. Each graph network module

is preceded by two multi-layer perceptrons (known as Dense layers in Keras

terminology), constituting a MEGNet block. Multiple MEGNet blocks can be

stacked, allowing for information flow across greater spatial distances. The

number of blocks required depend on the range of interactions necessary to

predict a target property. In the final step, a set2set is used to map the

output to a scalar/vector property.

Megnet can be installed via pip for the latest stable version:

pip install megnetFor the latest dev version, please clone this repo and install using:

python setup.py developOur current implementation supports a variety of use cases for users with different requirements and experience with deep learning. Please also visit the notebooks directory for Jupyter notebooks with more detailed code examples.

In our work, we have already built MEGNet models for the QM9 data set and

Materials Project dataset. These models are provided as serialized HDF5+JSON

files. Users who are purely interested in using these models for prediction

can quickly load and use them via the convenient MEGNetModel.from_file

method. These models are available in the mvl_models folder of this repo.

The following models are available:

- QM9 molecule data:

- HOMO: Highest occupied molecular orbital energy

- LUMO: Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy

- Gap: energy gap

- ZPVE: zero point vibrational energy

- µ: dipole moment

- α: isotropic polarizability

- <R2>: electronic spatial extent

- U0: internal energy at 0 K

- U: internal energy at 298 K

- H: enthalpy at 298 K

- G: Gibbs free energy at 298 K

- Cv: heat capacity at 298 K

- ω1: highest vibrational frequency.

- Materials Project data:

- Formation energy from the elements

- Band gap

- Log 10 of Bulk Modulus (K)

- Log 10 of Shear Modulus (G)

The MAEs on the various models are given below:

| Property | Units | MAE |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO | eV | 0.043 |

| LUMO | eV | 0.044 |

| Gap | eV | 0.066 |

| ZPVE | meV | 1.43 |

| µ | Debye | 0.05 |

| α | Bohr^3 | 0.081 |

| <R2> | Bohr^2 | 0.302 |

| U0 | eV | 0.012 |

| U | eV | 0.013 |

| H | eV | 0.012 |

| G | eV | 0.012 |

| Cv | cal/(molK) | 0.029 |

| ω1 | cm^-1 | 1.18 |

| Property | Units | MAE |

|---|---|---|

| Ef | eV/atom | 0.028 |

| Eg | eV | 0.33 |

| K_VRH | log10(GPa) | 0.050 |

| G_VRH | log10(GPa) | 0.079 |

| Property | Units | MAE |

|---|---|---|

| Ef | eV/atom | 0.026 |

| Efermi | eV | 0.288 |

New models will be added as they are developed in the mvl_models folder. Each folder contains a summary of model details and benchmarks. For the initial models and bencharmks comparison to previous models, please refer to "Graph Networks as a Universal Machine Learning Framework for Molecules and Crystals"[2].

Below is an example of crystal model usage:

from megnet.models import MEGNetModel

from pymatgen import MPRester

model = MEGNetModel.from_file('mvl_models/mp-2018.6.1/log10K.hdf5')

# We can grab a crystal structure from the Materials Project.

mpr = MPRester()

structure = mpr.get_structure_by_material_id('mp-1143')

# Use the model to predict bulk modulus K. Note that the model is trained on

# log10 K. So a conversion is necessary.

predicted_K = 10 ** model.predict_structure(structure).ravel()

print('The predicted K for {} is {} GPa'.format(structure.formula, predicted_K[0]))A full example is in notebooks/crystal_example.ipynb.

For molecular models, we have an example in

notebooks/qm9_pretrained.ipynb.

We support prediction directly from a pymatgen molecule object. With a few more

lines of code, the model can predict from SMILES representation of molecules,

as shown in the example. It is also straightforward to load a xyz molecule

file with pymatgen and predict the properties using the models. However, the

users are generally not advised to use the qm9 molecule models for other

molecules outside the qm9 datasets, since the training data coverage is

limited.

Below is an example of predicting the "HOMO" of a smiles representation

from megnet.utils.model_utils import QM9Model

model = QM9Model('HOMO')

model.predict_smiles("C")For users who wish to build a new model from a set of crystal structures with

corresponding properties, there is a convenient MEGNetModel class for setting

up and training the model. By default, the number of MEGNet blocks is 3 and the

atomic number Z is used as the only node feature (with embedding).

from megnet.models import MEGNetModel

from megnet.data.graph import GaussianDistance

from megnet.data.crystal import CrystalGraph

import numpy as np

nfeat_bond = 10

nfeat_global = 2

r_cutoff = 5

gaussian_centers = np.linspace(0, 5, 10)

gaussian_width = 0.5

distance_convertor = GaussianDistance(gaussian_centers, gaussian_width)

bond_convertor = CrystalGraph(bond_convertor=distance_convertor, cutoff=r_cutoff)

model = MEGNetModel(nfeat_bond, nfeat_global,

graph_convertor=graph_convertor)

# Model training

# Here, `structures` is a list of pymatgen Structure objects.

# `targets` is a corresponding list of properties.

model.train(structures, targets, epochs=10)

# Predict the property of a new structure

pred_target = model.predict_structure(new_structure)In some cases, some structures within the training pool may not be valid (containing isolated atoms),

then one needs to use train_from_graphs method by training only on the valid graphs.

Following the previous example,

model = MEGNetModel(nfeat_bond, nfeat_global, graph_convertor=graph_convertor)

graphs_valid = []

targets_valid = []

structures_invalid = []

for s, p in zip(structures, targets):

try:

graph = model.graph_convertor.convert(s)

graphs_valid.append(graph)

targets_valid.append(p)

except:

structures_invalid.append(s)

# train the model using valid graphs and targets

model.train_from_graphs(graphs_valid, targets_valid)For model details and benchmarks, please refer to "Graph Networks as a Universal Machine Learning Framework for Molecules and Crystals"[2]

A key finding of our work is that element embeddings from trained formation energy models encode useful chemical information that can be transferred learned to develop models with smaller datasets (e.g. elastic constants, band gaps), with better converegence and lower errors. These embeddings are also potentially useful in developing other ML models and applications. These embeddings have been made available via the following code:

from megnet.data.crystal import get_elemental_embeddings

el_embeddings = get_elemental_embeddings()

An example of transfer learning using the elemental embedding from formation energy to other models, please check notebooks/transfer_learning.ipynb.

For users who are familiar with deep learning and Keras and wish to build

customized graph network based models, the following example outlines how a

custom model can be constructed from MEGNetLayer, which is essentially our

implementation of the graph network using neural networks:

from keras.layers import Input, Dense

from keras.models import Model

from megnet.layers import MEGNetLayer, Set2Set

n_atom_feature= 20

n_bond_feature = 10

n_global_feature = 2

# Define model inputs

int32 = 'int32'

x1 = Input(shape=(None, n_atom_feature)) # atom feature placeholder

x2 = Input(shape=(None, n_bond_feature)) # bond feature placeholder

x3 = Input(shape=(None, n_global_feature)) # global feature placeholder

x4 = Input(shape=(None,), dtype=int32) # bond index1 placeholder

x5 = Input(shape=(None,), dtype=int32) # bond index2 placeholder

x6 = Input(shape=(None,), dtype=int32) # atom_ind placeholder

x7 = Input(shape=(None,), dtype=int32) # bond_ind placeholder

xs = [x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7]

# Pass the inputs to the MEGNetLayer layer

# Here the list are the hidden units + the output unit,

# you can have others like [n1] or [n1, n2, n3 ...] if you want.

out = MEGNetLayer([32, 16], [32, 16], [32, 16], pool_method='mean', activation='relu')(xs)

# the output is a tuple of new graphs V, E and u

# Since u is a per-structure quantity,

# we can directly use it to predict per-structure property

out = Dense(1)(out[2])

# Set up the model and compile it!

model = Model(inputs=xs, outputs=out)

model.compile(loss='mse', optimizer='adam')With less than 20 lines of code, you have built a graph network model that is ready for materials property prediction!

Graph networks[1] are a superclass of graph-based neural networks. There are a few innovations compared to conventional graph-based neural neworks.

- Global state attributes are added to the node/edge graph representation. These features work as a portal for structure-independent features such as temperature, pressure etc and also are an information exchange placeholder that facilitates information passing across longer spatial domains.

- The update function involves the message interchange among all three levels of information, i.e., the node, bond and state information. It is therefore a highly general model.

The MEGNet model implements two major components: (a) the graph network

layer and (b) the set2set layer.[3] The layers are based on

keras API and is thus compatible with other keras modules.

Different crystals/molecules have different number of atoms. Therefore it is

impossible to use data batches without padding the structures to make them

uniform in atom number. MEGNet takes a different approach. Instead of making

structure batches, we assemble many structures into one giant structure, and

this structure has a vector output with each entry being the target value for

the corresponding structure. Therefore, the batch number is always 1.

Assuming a structure has N atoms and M bonds, a structure graph is represented

as V (nodes/vertices, representing atoms), E (edges, representing bonds)

and u (global state vector). V is a N*Nv matrix. E comprises of a

M*Nm matrix for the bond attributes and index pairs (rk, sk) for atoms

connected by each bond. u is a vector with length Nu. We vectorize rk and

sk to form index1 and index2, both are vectors with length M. In summary,

the graph is a data structure with V (N*Nv), E (M*Nm), u

(Nu, ), index1 (M, ) and index2 (M, ).

We then assemble several structures together. For V, we directly append the

atomic attributes from all structures, forming a matrix (1*N'*Nv), where

N' > N. To indicate the belongingness of each atom attribute vector, we use a

atom_ind vector. For example if N'=5 and the first 3 atoms belongs to the

first structure and the remainings the second structure, our atom_ind vector

would be [0, 0, 0, 1, 1]. For the bond attribute, we perform the same

appending method, and use bond_ind vector to indicate the bond belongingness.

For index1 and index2, we need to shift the integer values. For example,

if index1 and index2 are [0, 0, 1, 1] and [1, 1, 0, 0] for structure 1

and are [0, 0, 1, 1] and [1, 1, 0, 0] for structure two. The assembled

indices are [0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3] and [1, 1, 0, 0, 3, 3, 2, 2]. Finally,

u expands a new dimension to take into account of the number of structures,

and becomes a 1*Ng*Nu tensor, where Ng is the number of structures. 1 is

added as the first dimension of all inputs because we fixed the batch size to

be 1 (1 giant graph) to comply the keras inputs requirements.

In summary the inputs for the model is V (1*N'*Nv), E (1*M'*Nm),

u (1*Ng*Nu), index1 (1*M'), index2 (1*M'), atom_ind (1*N'), and

bond_ind (1*M'). For Z-only atomic features, V is a (1*N') vector.

To aid others in reproducing (and improving on) our results, we have provided our MP-crystals-2018.6.1 crystal data set via figshare[4]. The MP-crystals-2018.6.1 data set comprises the DFT-computed energies and band gaps of 69,640 crystals from the Materials Project obtained via the Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen) interface to the Materials Application Programming Interface (API)[5] on June 1, 2018. The crystal graphs were constructed using a radius cut-off of 4 angstroms. Using this cut-off, 69,239 crystals do not form isolated atoms and are used in the models. A subset of 5,830 structures have elasticity data that do not have calculation warnings and will be used for elasticity models.

The molecule data set used in this work is the QM9 data set 30 processed by Faber et al.[6] It contains the B3LYP/6-31G(2df,p)-level DFT calculation results on 130,462 small organic molecules containing up to 9 heavy atoms.

Training: It should be noted that training MEGNet models, like other deep learning models, is fairly computationally intensive with large datasets. In our work, we use dedicated GPU resources to train MEGNet models with 100,000 crystals/molecules. It is recommended that you do the same.

Prediction: Once trained, prediction using MEGNet models are fairly cheap. For example, the http://megnet.crystals.ai web app runs on a single hobby dyno on Heroku and provides the prediction for any crystal within seconds.

isolated atomserror. This error occurs when using the given cutoff in the model (4A for 2018 models and 5A for 2019 models), the crystal structure contains isolated atoms, i.e., no neighboring atoms are within the distance ofcutoff. Most of the time, we can just discard the structure, since we found that those structures tend to have a high energy above hull (less stable). If you think this error is an essential issue for a particular problem, please feel free to email us and we will consider releasing a new model with increased cutoff.

- Battaglia, P. W.; Hamrick, J. B.; Bapst, V.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Zambaldi, V.; Malinowski, M.; Tacchetti, A.; Raposo, D.; Santoro, A.; Faulkner, R.; et al. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. 2018, 1–38. arXiv:1806.01261

- Chen, C.; Ye, W.; Zuo, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ong, S. P. Graph Networks as a Universal Machine Learning Framework for Molecules and Crystals. Chemistry of Materials 2019, acs.chemmater.9b01294. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01294

- Vinyals, O.; Bengio, S.; Kudlur, M. Order Matters: Sequence to sequence for sets. 2015, arXiv preprint. arXiv:1511.06391

- https://figshare.com/articles/Graphs_of_materials_project/7451351

- Ong, S. P.; Cholia, S.; Jain, A.; Brafman, M.; Gunter, D.; Ceder, G.; Persson, K. A. The Materials Application Programming Interface (API): A simple, flexible and efficient API for materials data based on REpresentational State Transfer (REST) principles. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 97, 209–215 DOI: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.10.037.

- Faber, F. A.; Hutchison, L.; Huang, B.; Gilmer, J.; Schoenholz, S. S.; Dahl, G. E.; Vinyals, O.; Kearnes, S.; Riley, P. F.; von Lilienfeld, O. A. Prediction errors of molecular machine learning models lower than hybrid DFT error. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2017, 13, 5255–5264. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00577