Here's how to compress 24 bytes of data down to 2 using Fibonacci coding:

// Instantiate the codec ready to compress

Codec codec = new FibonacciCodec(); // Replace with any codec

// Compress data - 3x8 bytes = 24bytes uncompressed

var compressed = codec.CompressSigned(new long[] { 1, 2, 3 }); // Note: Unsigned compression is more effective than signed

Console.WriteLine("Compressed data is " + compressed.Length + " bytes"); // Output: Compressed data is 2 bytes

// Decompress data

var decompressed = codec.DecompressSigned(compressed, 3);

Console.WriteLine(String.Join(",", decompressed)); // Output: 1,2,3Modern PCs have stacks of RAM, so it's usually not a problem that integers take 4-8 bytes each to store in memory. There are times however when this is a problem. For exammple:

- When you want to store a large set of numbers in memory (100 million * 8 bytes = 760MB)

- When you want to store a large set of numbers on disk

- When you want to transmit numbers over a network (the Internet?) quickly

In almost all cases those numbers can be stored in a much lower number of bytes. Heck, its possible to store three integers in a single byte.

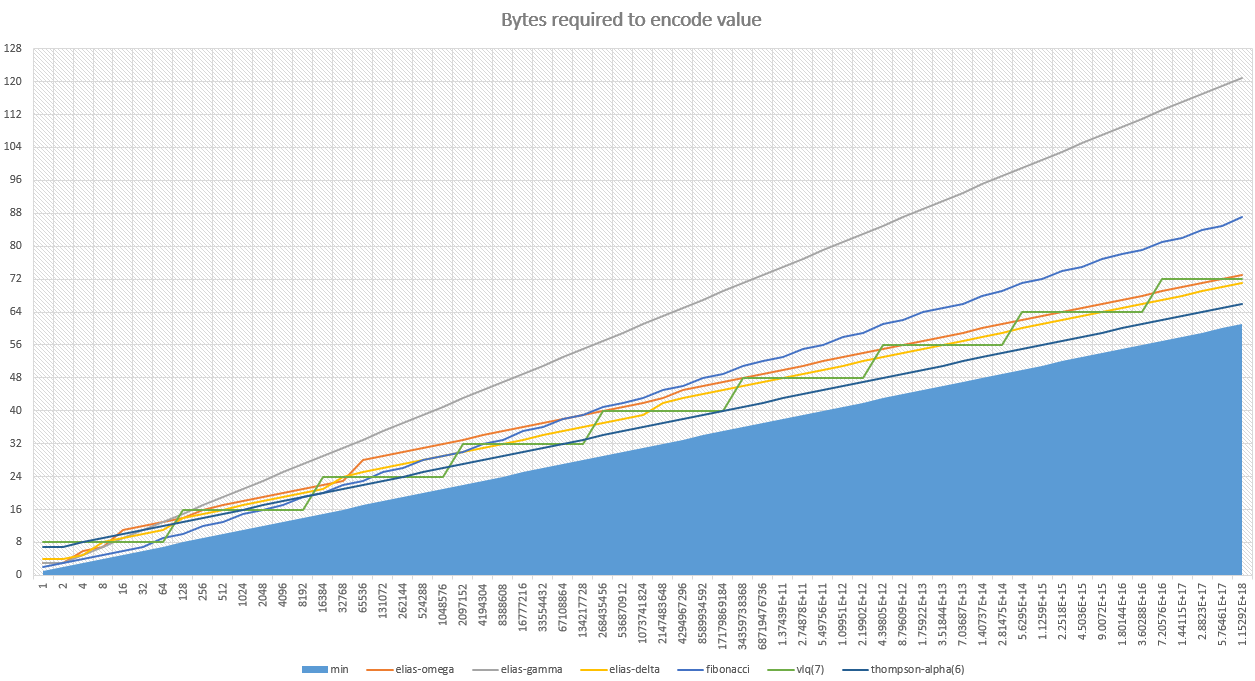

The example in the TLDR section used the Fibonacci codec. Whilst this codec is excellent for small numbers, it's not so great when numbers get larger. You really need to select a codec with your domain in mind. Following is a summary of the codecs available, their strengths and weaknesses.

Keep in mind that there is a physical minimum possible size for each number. That is displayed in blue.

- Family: universal code

- Random access: yes (can jump ahead)

- Lossy: no (doesn't approximate)

- Universal: yes (can handle any number)

- Details: Wikipedia

- Options:

This is a very interesting algorithm - it encodes the numbers against a Fibonacci sequence. It's the best algorithm in the pack for numbers up to 8,000, It degrades after that point - but not horrendously so. This is my personal favorite algo.

- Family: none

- Random access: no

- Universal: no (can only handle a predefined range of numbers)

- Details: N/A

- Options:

- Length bits

I couldn't find an algorithm which performed well for large integers (>8,000), so this is my own. In it's default configuration it has a flat 6-bits of overhead for each integer, no matter it's size. That makes it excellent if your numbers have a large distribution.

** This uses the legacy interface. See notes below. **

- Random access: no (can't jump ahead)

- Universal: yes (can handle any number)

- Details: Wikipedia

- Options:

- Packet size

It seems VLQ was originally invented by the designers of MIDI (you know, the old-school MP3). The algorithm is really retro, there's stacks of variations of it's spec and it smells a little musty, but it's awesome! It produces pretty good results for all numbers with a very low CPU overhead.

- Family: universal code

- Random access: no (can't jump ahead)

- Universal: yes (can handle any number)

- Supported values: all

- Details: Wikipedia

Elias Omega is a sexy algorithm. It's well thought out and utterly brilliant. But I wouldn't use it. It does well for tiny integers (under 8), but just doesn't cut the mustard after that. Sorry Omega :-/.

** This uses the legacy interface. See notes below. **

- Family: universal code

- Random access: no (can't jump ahead)

- Universal: yes (can handle any number)

- Supported values: all

- Details: Wikipedia

Like Elias-Omega, this is a very interesting algorithm. However it's only really useful for small integers (less than 8). For bigger numbers it performs terribly.

** This uses the legacy interface. See notes below. **

- Family: universal code

- Random access: no (can't jump ahead)

- Universal: yes (can handle any number)

- Supported values: all

- Details: Wikipedia

I have a lot of respect for this algorithm. It's an all-rounder, doing well on small numbers and large alike. If you knew you were mostly going to have small numbers, but you'd have a some larger ones as well, this would be my choice. The algorithm is a little complex, so you might be cautious if you have extreme CPU limitations.

** This uses the legacy interface. See notes below. **

I've recently started porting the algorithms to a new easier-to-use interface (see TLDR above), however there's a few codecs that haven't made the transition yet. To use these with the legacy interface use the reader/writter pattern as below:

using (var stream = new MemoryStream()) {

// Make a writer to encode values onto your stream

using (var writer = new FibonacciUnsignedWriter(stream)) { // Fibonacci is just one algorithm

// Write 1st value

writer.Write(1); // 8 bytes in memory

// Write 2nd value

writer.Write(2); // 8 bytes in memory

// Write 3rd value

writer.Write(3); // 8 bytes in memory

}

Console.WriteLine("Compressed data is " + stream.Length + " bytes"); // Output: Compressed data is 2 bytes

// Rewind the stream

stream.Position = 0;

// Make a reader to decode values from your stream

using (var reader = new FibonacciUnsignedReader(stream)) {

Console.WriteLine(reader.Read());

// Output: 1

Console.WriteLine(reader.Read());

// Output: 2

Console.WriteLine(reader.Read());

// Output: 3

}

}In order to make an accurate assessment of a codec for your purpose, some

algorithms have a method CalculateBitLength that allows you to know

how many bits a given value would consume when encoded. I recommend getting a set

of your data and running it through the CalculateBitLength methods of a few

algorithms to see which one is best.

If your numbers are unsigned (eg, no negatives), be sure to use unsigned encoding. That way you'll get the best compression. Obviously fall back to signed if you must.

There are a few techniques you can use to further increase the compression of your integers. Following is a summary of each

Even with compression, smaller numbers use less space. So take a moment to consider what you can do to keep your numbers small. One common technique is to store the difference between numbers instead of the numbers themselves. Consider if you wanted to store the following sequence:

- 10000

- 10001

- 10002

- 10003

- 10004

If you converted them to deltas you could instead store:

- 1000

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

This sequence uses a stack less bytes!

Naturally this isn't suitable for all contexts. If the receiver has the potential to loose state (eg. UDP transport) you'll have to include a recovery mechanism (eg keyframes), otherwise those deltas become meaningless.

Sometimes it's okay to loose data in compression. Let's say that you're compressing a list of distances in meters, however you only really care about the distance rounded to the nearest 100 meters. You can save a heap of data by dividing your value by 100 before compressing it, and multiplying it by 100 after.

Sometimes all of your values are always going to be above zero. Let's say that you're storing the number of cars going over a busy bridge each hour. If it's safe to assume there will never be 0 cars you could save some data by subtracting one from your value before compression and adding one after decompression.

This may seem like a trivial optimization, however with most algorithms it will save you one or two bits per number. If you have several million numbers that really adds up.