| Usage | Release | Development |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data analysis can be slow. A round of scientific computation can take several minutes, hours, or even days to complete. After it finishes, if you update your code or data, your hard-earned results may no longer be valid. How much of that valuable output can you keep, and how much do you need to update? How much runtime must you endure all over again?

For projects in R, the drake package can help. It analyzes your

workflow, skips steps with

up-to-date results, and orchestrates the rest with optional distributed

computing. At the end,

drake provides evidence that your results match the underlying code

and data, which increases your ability to trust your research.

The rOpenSci Community Call

from 2019-09-24 is a

thorough introduction to drake (20 min talk, 35 min Q&A). Visit the

call’s page for links to

additional resources, and chime in

here to propose and

vote for ideas for new Community Call topics and speakers.

Too many data science projects follow a Sisyphean loop:

- Launch the code.

- Wait while it runs.

- Discover an issue.

- Rerun from scratch.

For projects with long runtimes, this process gets tedious. But with

drake, you can automatically

- Launch the parts that changed since last time.

- Skip the rest.

To set up a project, load your packages,

library(drake)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'tidyr'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:drake':

#>

#> expand, gatherload your custom functions,

create_plot <- function(data) {

ggplot(data) +

geom_histogram(aes(x = Ozone)) +

theme_gray(24)

}check any supporting files (optional),

# Get the files with drake_example("main").

file.exists("raw_data.xlsx")

#> [1] TRUE

file.exists("report.Rmd")

#> [1] TRUEand plan what you are going to do.

plan <- drake_plan(

raw_data = readxl::read_excel(file_in("raw_data.xlsx")),

data = raw_data %>%

mutate(Ozone = replace_na(Ozone, mean(Ozone, na.rm = TRUE))),

hist = create_plot(data),

fit = lm(Ozone ~ Wind + Temp, data),

report = rmarkdown::render(

knitr_in("report.Rmd"),

output_file = file_out("report.html"),

quiet = TRUE

)

)

plan

#> # A tibble: 5 x 2

#> target command

#> <chr> <expr>

#> 1 raw_data readxl::read_excel(file_in("raw_data.xlsx")) …

#> 2 data raw_data %>% mutate(Ozone = replace_na(Ozone, mean(Ozone, na.rm = TR…

#> 3 hist create_plot(data) …

#> 4 fit lm(Ozone ~ Wind + Temp, data) …

#> 5 report rmarkdown::render(knitr_in("report.Rmd"), output_file = file_out("re…So far, we have just been setting the stage. Use make() or

r_make()

to do the real work. Targets are built in the correct order regardless

of the row order of plan.

make(plan) # See also r_make().

#> ▶ target raw_data

#> ▶ target data

#> ▶ target fit

#> ▶ target hist

#> ▶ target reportExcept for files like report.html, your output is stored in a hidden

.drake/ folder. Reading it back is easy.

readd(data) # See also loadd().

#> # A tibble: 153 x 6

#> Ozone Solar.R Wind Temp Month Day

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 41 190 7.4 67 5 1

#> 2 36 118 8 72 5 2

#> 3 12 149 12.6 74 5 3

#> 4 18 313 11.5 62 5 4

#> 5 42.1 NA 14.3 56 5 5

#> 6 28 NA 14.9 66 5 6

#> 7 23 299 8.6 65 5 7

#> 8 19 99 13.8 59 5 8

#> 9 8 19 20.1 61 5 9

#> 10 42.1 194 8.6 69 5 10

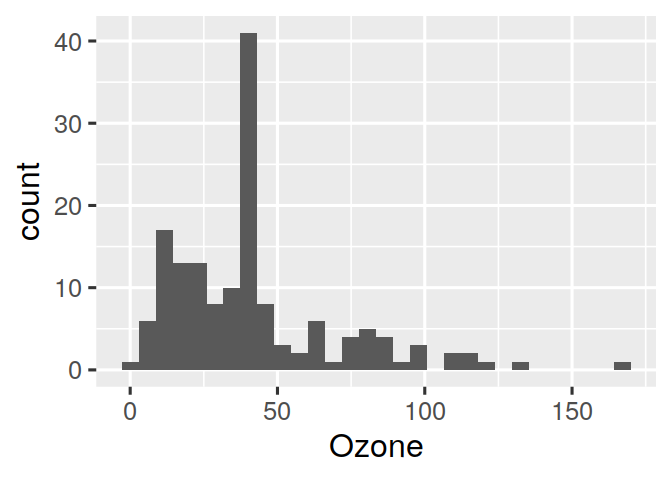

#> # … with 143 more rowsYou may look back on your work and see room for improvement, but it’s

all good! The whole point of drake is to help you go back and change

things quickly and painlessly. For example, we forgot to give our

histogram a bin width.

readd(hist)

#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.So let’s fix the plotting function.

create_plot <- function(data) {

ggplot(data) +

geom_histogram(aes(x = Ozone), binwidth = 10) +

theme_gray(24)

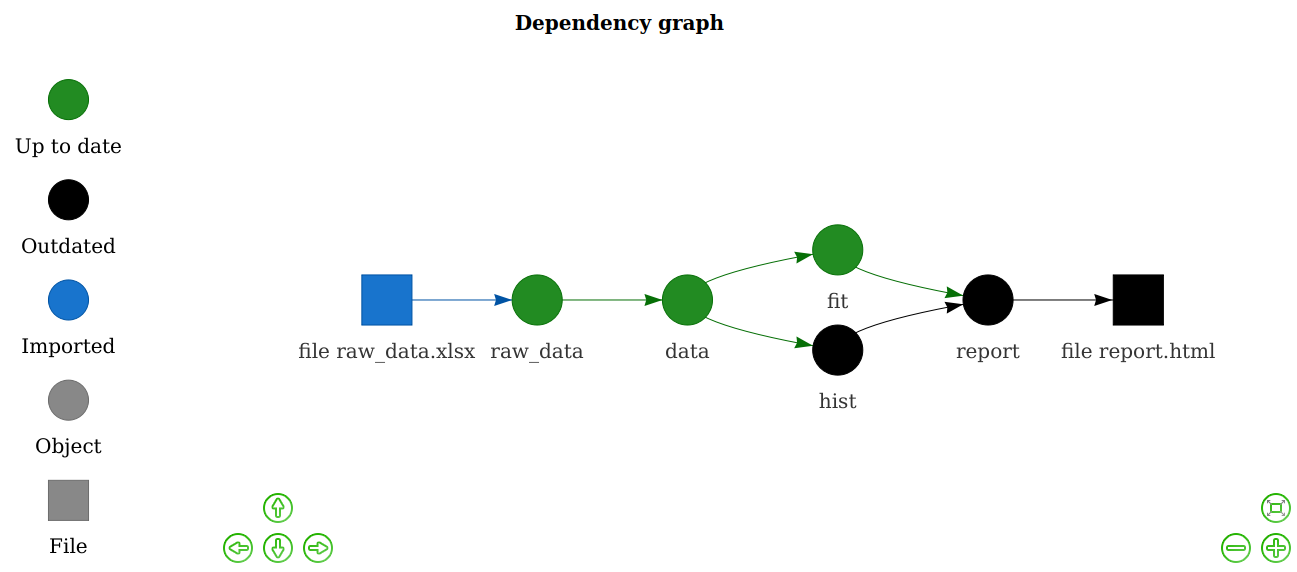

}drake knows which results are

affected.

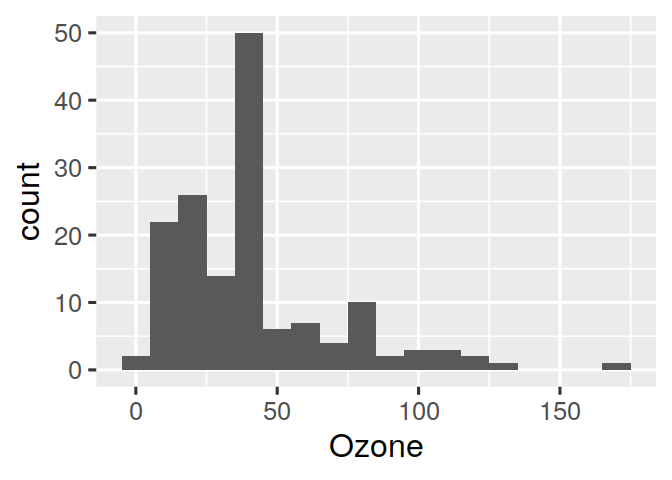

vis_drake_graph(plan) # See also r_vis_drake_graph().The next make() just builds hist and report.html. No point in

wasting time on the data or model.

make(plan) # See also r_make().

#> ▶ target hist

#> ▶ target reportloadd(hist)

histThe R community emphasizes reproducibility. Traditional themes include

scientific

replicability,

literate programming with knitr, and

version control with

git.

But internal consistency is important too. Reproducibility carries the

promise that your output matches the code and data you say you used.

With the exception of non-default

triggers and hasty

mode, drake

strives to keep this promise.

Suppose you are reviewing someone else’s data analysis project for

reproducibility. You scrutinize it carefully, checking that the datasets

are available and the documentation is thorough. But could you re-create

the results without the help of the original author? With drake, it is

quick and easy to find out.

make(plan) # See also r_make().

#> ℹ unloading 1 targets from environment

#> ✓ All targets are already up to date.

outdated(plan) # See also r_outdated().

#> character(0)With everything already up to date, you have tangible evidence of reproducibility. Even though you did not re-create the results, you know the results are recreatable. They faithfully show what the code is producing. Given the right package environment and system configuration, you have everything you need to reproduce all the output by yourself.

When it comes time to actually rerun the entire project, you have much more confidence. Starting over from scratch is trivially easy.

clean() # Remove the original author's results.

make(plan) # Independently re-create the results from the code and input data.

#> ▶ target raw_data

#> ▶ target data

#> ▶ target fit

#> ▶ target hist

#> ▶ target reportSelect specialized data formats to increase speed and reduce memory consumption. In version 7.5.2.9000 and above, the available formats are “fst” for data frames (example below) and “keras” for Keras models (example here).

library(drake)

n <- 1e8 # Each target is 1.6 GB in memory.

plan <- drake_plan(

data_fst = target(

data.frame(x = runif(n), y = runif(n)),

format = "fst"

),

data_old = data.frame(x = runif(n), y = runif(n))

)

make(plan)

#> target data_fst

#> target data_old

build_times(type = "build")

#> # A tibble: 2 x 4

#> target elapsed user system

#> <chr> <Duration> <Duration> <Duration>

#> 1 data_fst 13.93s 37.562s 7.954s

#> 2 data_old 184s (~3.07 minutes) 177s (~2.95 minutes) 4.157sAs of version 7.5.2, drake tracks the history and provenance of your

targets: what you built, when you built it, how you built it, the

arguments you used in your function calls, and how to get the data back.

(Disable with make(history = FALSE))

history <- drake_history(analyze = TRUE)

history

#> # A tibble: 12 x 11

#> target current built exists hash command seed runtime na.rm quiet

#> <chr> <lgl> <chr> <lgl> <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl>

#> 1 data TRUE 2020… TRUE 11e2… "raw_d… 1.29e9 0.0160 TRUE NA

#> 2 data TRUE 2020… TRUE 11e2… "raw_d… 1.29e9 0.004 TRUE NA

#> 3 fit TRUE 2020… TRUE 3c87… "lm(Oz… 1.11e9 0.00300 NA NA

#> 4 fit TRUE 2020… TRUE 3c87… "lm(Oz… 1.11e9 0.00100 NA NA

#> 5 hist FALSE 2020… TRUE 82b9… "creat… 2.10e8 0.012 NA NA

#> 6 hist TRUE 2020… TRUE 2170… "creat… 2.10e8 0.004 NA NA

#> 7 hist TRUE 2020… TRUE 2170… "creat… 2.10e8 0.007 NA NA

#> 8 raw_d… TRUE 2020… TRUE 855d… "readx… 1.20e9 0.00900 NA NA

#> 9 raw_d… TRUE 2020… TRUE 855d… "readx… 1.20e9 0.008 NA NA

#> 10 report TRUE 2020… TRUE c09a… "rmark… 1.30e9 0.655 NA TRUE

#> 11 report TRUE 2020… TRUE c09a… "rmark… 1.30e9 0.400 NA TRUE

#> 12 report TRUE 2020… TRUE c09a… "rmark… 1.30e9 0.405 NA TRUE

#> # … with 1 more variable: output_file <chr>Remarks:

- The

quietcolumn appears above because one of thedrake_plan()commands hasknit(quiet = TRUE). - The

hashcolumn identifies all the previous versions of your targets. As long asexistsisTRUE, you can recover old data. - Advanced: if you use

make(cache_log_file = TRUE)and put the cache log file under version control, you can match the hashes fromdrake_history()with thegitcommit history of your code.

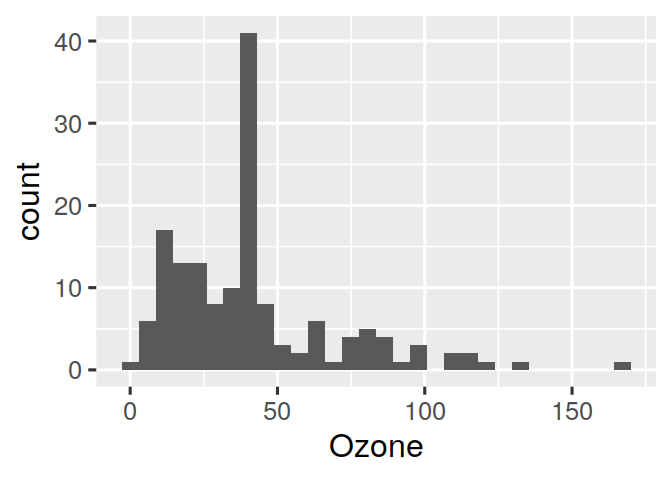

Let’s use the history to recover the oldest histogram.

hash <- history %>%

filter(target == "hist") %>%

pull(hash) %>%

head(n = 1)

cache <- drake_cache()

cache$get_value(hash)

#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.With even more evidence and confidence, you can invest the time to

independently replicate the original code base if necessary. Up until

this point, you relied on basic drake functions such as make(), so

you may not have needed to peek at any substantive author-defined code

in advance. In that case, you can stay usefully ignorant as you

reimplement the original author’s methodology. In other words, drake

could potentially improve the integrity of independent replication.

Ideally, independent observers should be able to read your code and

understand it. drake helps in several ways.

- The drake

plan

explicitly outlines the steps of the analysis, and

vis_drake_graph()visualizes how those steps depend on each other. draketakes care of the parallel scheduling and high-performance computing (HPC) for you. That means the HPC code is no longer tangled up with the code that actually expresses your ideas.- You can generate large collections of targets without necessarily changing your code base of imported functions, another nice separation between the concepts and the execution of your workflow

Not every project can complete in a single R session on your laptop.

Some projects need more speed or computing power. Some require a few

local processor cores, and some need large high-performance computing

systems. But parallel computing is hard. Your tables and figures depend

on your analysis results, and your analyses depend on your datasets, so

some tasks must finish before others even begin. drake knows what to

do. Parallelism is implicit and automatic. See the high-performance

computing guide for all the

details.

# Use the spare cores on your local machine.

make(plan, jobs = 4)

# Or scale up to a supercomputer.

drake_hpc_template_file("slurm_clustermq.tmpl") # https://slurm.schedmd.com/

options(

clustermq.scheduler = "clustermq",

clustermq.template = "slurm_clustermq.tmpl"

)

make(plan, parallelism = "clustermq", jobs = 4)drake and Docker are compatible and complementary. Here are some

examples that run drake inside a Docker

image.

drake-gitlab-docker-example: A small pedagogical example workflow that leveragesdrake, Docker, GitLab, and continuous integration in a reproducible analysis pipeline. Created by Noam Ross.pleurosoriopsis: The workflow that supports Ebihara et al. 2019. “Growth Dynamics of the Independent Gametophytes of Pleurorosiopsis makinoi (Polypodiaceae)” Bulletin of the National Science Museum Series B (Botany) 45:77-86.. Created by Joel Nitta.

Alternatively, it is possible to run drake outside Docker and use the

future package to send

targets to a Docker image. drake’s

Docker-psock

example demonstrates how. Download the code with

drake_example("Docker-psock").

You can choose among different versions of drake. The CRAN release

often lags behind the online manual

but may have fewer bugs.

# Install the latest stable release from CRAN.

install.packages("drake")

# Alternatively, install the development version from GitHub.

install.packages("devtools")

library(devtools)

install_github("ropensci/drake")The reference section lists all the available functions. Here are the most important ones.

drake_plan(): create a workflow data frame (likemy_plan).make(): build your project.drake_history(): show what you built, when you built it, and the function arguments you used.r_make(): launch a freshcallr::r()process to build your project. Called from an interactive R session,r_make()is more reproducible thanmake().loadd(): load one or more built targets into your R session.readd(): read and return a built target.vis_drake_graph(): show an interactive visual network representation of your workflow.recoverable(): Which targets can we salvage usingmake(recover = TRUE)(experimental).outdated(): see which targets will be built in the nextmake().deps_code(): check the dependencies of a command or function.drake_failed(): list the targets that failed to build in the lastmake().diagnose(): return the full context of a build, including errors, warnings, and messages.

The following resources explain what drake can do and how it works.

The learndrake workshop

devotes particular attention to drake’s mental model.

- The user manual

drakeplanner, an R/Shiny app to help learndrakeand create new projects. Run locally withdrakeplanner::drakeplanner()or access it at https://wlandau.shinyapps.io/drakeplanner.learndrake, an R package for teaching an extendeddrakeworkshop. It contains notebooks, slides, Shiny apps, the latter two of which are publicly deployed. See the README for instructions and links.

- Miles McBain’s excellent blog post explains the motivating factors and practical issues {drake} solves for most projects, how to set up a project as quickly and painlessly as possible, and how to overcome common obstacles.

- Miles’

dflowpackage generates the file structure for a boilerplatedrakeproject. It is a more thorough alternative todrake::use_drake(). drakeis heavily function-oriented by design, and Miles’fnmatepackage automatically generates boilerplate code and docstrings for functions you mention indrakeplans.

- The reference website.

- The official repository of example

code. Download an

example workflow from here with

drake_example(). - Presentations and workshops by Will Landau, Kirill Müller, Amanda Dobbyn, Karthik Ram, Sina Rüeger, Christine Stawitz, and others. See specific links at https://books.ropensci.org/drake/index.html#presentations

- The FAQ page, which links to appropriately-labeled issues on GitHub.

The official rOpenSci use

cases and associated

discussion threads describe

applications of drake in the real world. Many of these use cases are

linked from the drake tag on the rOpenSci discussion

forum.

Here are some additional applications of drake in real-world

projects.

- efcaguab/demografia-del-voto

- efcaguab/great-white-shark-nsw

- IndianaCHE/Detailed-SSP-Reports

- joelnitta/pleurosoriopsis

- pat-s/pathogen-modeling

- sol-eng/tensorflow-w-r

- tiernanmartin/home-and-hope

Some folks like to structure their drake workflows as R packages.

Examples are below. In your own analysis packages, be sure to call

drake::expose_imports(yourPackage) so drake can watch you package’s

functions for changes and rebuild downstream targets

accordingly.

The following resources document many known issues and challenges.

- Frequently-asked questions.

- Cautionary notes and edge cases

- Debugging and testing drake projects

- Other known issues (please search both open and closed ones).

If you are still having trouble, please submit a new issue with a bug report or feature request, along with a minimal reproducible example where appropriate.

The GitHub issue tracker is mainly intended for bug reports and feature

requests. While questions about usage etc. are also highly encouraged,

you may alternatively wish to post to Stack

Overflow and use the drake-r-package

tag.

Development is a community effort, and we encourage participation. Please read CONTRIBUTING.md for details.

drake enhances reproducibility and high-performance computing, but not

in all respects. Literate programming,

local library managers,

containerization, and strict session

managers offer more robust

solutions in their respective domains. And for the problems drake

does solve, it stands on the shoulders of the giants that came before.

The original idea of a time-saving reproducible build system extends back at least as far as GNU Make, which still aids the work of data scientists as well as the original user base of complied language programmers. In fact, the name “drake” stands for “Data Frames in R for Make”. Make is used widely in reproducible research. Below are some examples from Karl Broman’s website.

- Bostock, Mike (2013). “A map of flowlines from NHDPlus.” https://github.com/mbostock/us-rivers. Powered by the Makefile at https://github.com/mbostock/us-rivers/blob/master/Makefile.

- Broman, Karl W (2012). “Halotype Probabilities in Advanced

Intercross Populations.” G3 2(2), 199-202.Powered by the

Makefileat https://github.com/kbroman/ailProbPaper/blob/master/Makefile. - Broman, Karl W (2012). “Genotype Probabilities at Intermediate Generations in the Construction of Recombinant Inbred Lines.” *Genetics 190(2), 403-412. Powered by the Makefile at https://github.com/kbroman/preCCProbPaper/blob/master/Makefile.

- Broman, Karl W and Kim, Sungjin and Sen, Saunak and Ane, Cecile and

Payseur, Bret A (2012). “Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci onto a

Phylogenetic Tree.” Genetics 192(2), 267-279. Powered by the

Makefileat https://github.com/kbroman/phyloQTLpaper/blob/master/Makefile.

Whereas GNU Make is

language-agnostic, drake is fundamentally designed for R.

- Instead of a

Makefile,

drakesupports an R-friendly domain-specific language for declaring targets. - Targets in GNU Make are files,

whereas targets in

drakeare arbitrary variables in memory. (drakedoes have opt-in support for files viafile_out(),file_in(), andknitr_in().)drakecaches these objects in its own storage system so R users rarely have to think about output files.

remake itself is no longer maintained, but its founding design goals and principles live on through drake. In fact, drake is a direct re-imagining of remake with enhanced scalability, reproducibility, high-performance computing, visualization, and documentation.

Factual’s Drake is similar in concept, but the development effort is completely unrelated to the drake R package.

There are countless other successful pipeline

toolkits. The drake

package distinguishes itself with its R-focused approach,

Tidyverse-friendly interface, and a thorough selection of parallel

computing technologies and scheduling

algorithms.

Memoization is the strategic caching of the return values of functions.

It is a lightweight approach to the core problem that drake and other

pipeline tools are trying to solve. Every time a memoized function is

called with a new set of arguments, the return value is saved for future

use. Later, whenever the same function is called with the same

arguments, the previous return value is salvaged, and the function call

is skipped to save time. The

memoise package is the primary

implementation of memoization in R.

Memoization saves time for small projects, but it arguably does not go

far enough for large reproducible pipelines. In reality, the return

value of a function depends not only on the function body and the

arguments, but also on any nested functions and global variables, the

dependencies of those dependencies, and so on upstream. drake tracks

this deeper context, while memoise

does not.

Literate programming is the practice of narrating code in plain vernacular. The goal is to communicate the research process clearly, transparently, and reproducibly. Whereas commented code is still mostly code, literate knitr / R Markdown reports can become websites, presentation slides, lecture notes, serious scientific manuscripts, and even books.

drake and knitr are symbiotic. drake’s

job is to manage large computation and orchestrate the demanding tasks

of a complex data analysis pipeline.

knitr’s job is to communicate those

expensive results after drake computes them.

knitr / R

Markdown reports are small pieces of an

overarching drake pipeline. They should focus on communication, and

they should do as little computation as possible.

To insert a knitr report in a drake

pipeline, use the knitr_in() function inside your drake

plan, and use loadd()

and readd() to refer to targets in the report itself. See an example

here.

drake is not a version control tool. However, it is fully compatible

with git,

svn, and similar

software. In fact, it is good practice to use

git alongside drake for reproducible

workflows.

However, data poses a challenge. The datasets created by make() can

get large and numerous, and it is not recommended to put the .drake/

cache or the .drake_history/ logs under version control. Instead, it

is recommended to use a data storage solution such as

DropBox or

OSF.

drake does not track R packages or system dependencies for changes.

Instead, it defers to tools like Docker,

Singularity,

renv, and

packrat, which create

self-contained portable environments to reproducibly isolate and ship

data analysis projects. drake is fully compatible with these tools.

The workflowr package is a

project manager that focuses on literate programming, sharing over the

web, file organization, and version control. Its brand of

reproducibility is all about transparency, communication, and

discoverability. For an example of

workflowr and drake

working together, see this machine learning

project by Patrick

Schratz.

Special thanks to Jarad Niemi, my advisor from

graduate school, for first introducing me

to the idea of Makefiles for

research. He originally set me down the path that led to drake.

Many thanks to Julia Lowndes, Ben Marwick, and Peter Slaughter for reviewing drake for rOpenSci, and to Maëlle Salmon for such active involvement as the editor. Thanks also to the following people for contributing early in development.

- Alex Axthelm

- Chan-Yub Park

- Daniel Falster

- Eric Nantz

- Henrik Bengtsson

- Ian Watson

- Jasper Clarkberg

- Kendon Bell

- Kirill Müller

- Michael Schubert

Credit for images is attributed here.