by Jeffrey Emanuel (6/1/2024)

I periodically think about Hermann Grassmann and get sucked into reading about his life and work. Most people haven't heard of him, and even if they have, they can't tell you much about him. In short, he was a German polymath born in 1809. He was the son of an ordained minister who also taught math and physics at the local high school (technically, a Gymnasium) which Grassmann attended, and where he was not conspicuously brilliant or accomplished, although he was very good at music. Hermann then attended the University of Berlin, where he made the terrible choice in retrospect of studying theology with a sprinkling of classical languages.

What he should have majored in is math, since, as it turned out, he was an incredible world-class math genius. But he only realized that he liked math after he finished university and went back home to his hometown of Stettin (now a city in Poland), and by then, he wasn't in a position to receive the kind of rigorous and supervised formal training that is typical in math. Instead, he just taught himself from books and presumably from talking to his father. When he was just 23, he made his critical main discovery, which he basically spent the rest of his career explicating and exploring: he found a completely new way to "add" and "multiply" points and vectors in space.

After a year of this self-directed study, he tried to take the math examination that would allow him to teach high school math. But because of his late start and shaky fundamentals, he didn't get a particularly high score on this test, and thus was only permitted to teach lower level math. As an aside, this strikes me as totally laughable given the extremely low standards expected of the typical high school math teacher today, but back then, the standards were very different.

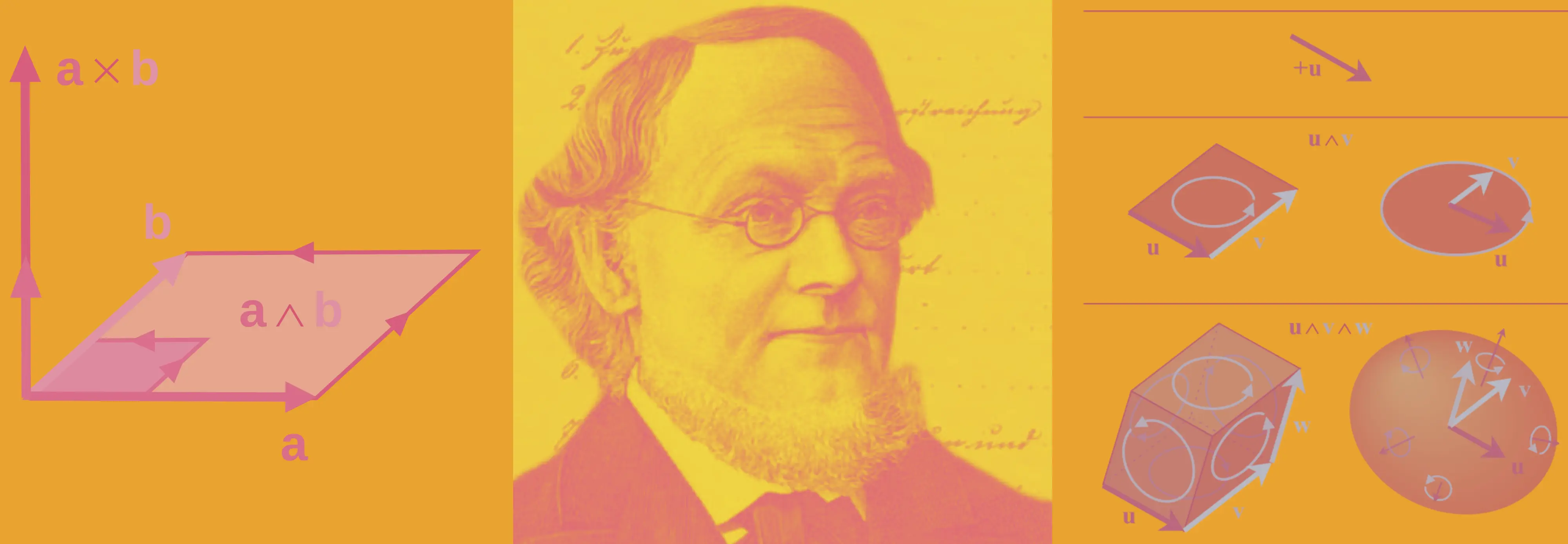

He didn't let this totally discourage him, though, and continued reading and learning math, and also started coming up with his own original mathematical ideas. To cut the story short, these ideas were totally revolutionary, and he ended up collecting them all several years later in his groundbreaking work, Die lineale Ausdehnungslehre, ein neuer Zweig der Mathematik (link), published in 1844 when he was 35. Grassmann essentially came up with a totally original and new conception of linear algebra. Instead of the more traditional development of systems of linear equations, vectors, matrices, determinants, etc., Grassmann had a more general and abstract conception of the subject, which focused on what is now known as an exterior algebra, also known as the "wedge product."

Unlike in the traditional development, where we use simpler operations like the dot product or cross product, in Grassmann's presentation of the subject, everything is couched in terms of the wedge product, which is a bit more abstract and harder to explain. In a nutshell, the wedge product of two vectors can be thought of as the region spanned by the vectors in space using the traditional parallelogram rule; it's basically what you probably already know as the determinant, but instead of representing the quantity of the area spanned by this space, it's the space itself.

Basically, the wedge product generalizes the determinant to higher dimensions and different contexts. While the determinant gives a scalar quantity representing the volume or area, the wedge product retains the geometric and algebraic structure of the span. The wedge product can be seen as a more general and geometric representation, while the determinant provides a specific scalar measure of that geometric entity. It's sort of beyond the scope of this informal article, but since I don't want anyone to complain that I'm being too vague and "hand wavy" here, I'll quickly give you the formal definition of the wedge product:

The wedge product is an antisymmetric bilinear operation on vectors in a vector space. For vectors

-

Antisymmetry:

$\mathbf{u} \wedge \mathbf{v} = -(\mathbf{v} \wedge \mathbf{u})$ . -

Bilinearity: The wedge product is linear in both arguments.

$(a\mathbf{u} + b\mathbf{v}) \wedge \mathbf{w} = a (\mathbf{u} \wedge \mathbf{w}) + b (\mathbf{v} \wedge \mathbf{w})$ -

Associativity: The wedge product can be extended to higher-order products:

$\mathbf{u} \wedge (\mathbf{v} \wedge \mathbf{w}) = (\mathbf{u} \wedge \mathbf{v}) \wedge \mathbf{w}$

I don't know about you, but even though the ideas aren't intrinsically that hard or complicated, it already seems extremely abstract and sort of hard to parse. What's that funky carrot ^ symbol again? How does the anti-symmetry come into play exactly? And that whole "bilinearity" thing— it seems like it's loading a lot of complexity in a single word/idea! Anyway, it turns out that if you make the bivector the fundamental object of consideration, and the wedge product the primary operation of consideration, a lot of very nice math sort of "falls out." And it also turns out that this approach can generalize in a less clunky way than the more traditional presentation of linear algebra to higher dimensions and to doing calculus in these higher dimensional spaces, not just algebra. If you just walk through the implications of the axioms about the wedge product and look at what you get when you take the wedge product of two 3-dimensional vectors, you quickly end up with something that looks very similar to how you compute determinants of a matrix recursively using minors and cofactors, and indeed, it's basically the exact same idea but in different notation.

But like I said, it somehow "feels" hard and too abstract, especially compared to a regular vector or regular matrix and doing dot products or matrix multiplication with those. Sure, the matrix multiplication formula does seem pretty complex when you first learn about it, but then it quickly becomes second nature and you can think of it as just a bunch of repeated dot products, and since the dot product is just simple element-wise multiplication, it doesn't seem too bad. And guess what? This was essentially the reaction of the world to Grassmann's first big paper: no one really read it or cared, not even other mathematicians. Grassmann wasn't known for being a mathematician. He studied religion, right? And he couldn't even get a good score on his teacher exams. And what was even the point of this weirdly abstract presentation?

Grassmann didn't do a great job of articulating why his approach was a good one; he didn't start with simpler, concrete examples using more straightforward ideas and notation and show how they could be used productively to solve problems in engineering or applied physics. He just immediately jumped into the full theory in all its generality and abstraction, as he probably imagined that pure mathematicians are supposed to do. After all, his new theory was basically a new foundation for all of mathematics as it then existed, so he had to make things super abstract to allow for that expressive power. Also, he treated everything in complete generality, so everything was done in N dimensions; he didn't focus first on the 3-dimensions that most people care about and can understand intuitively (partly because there isn't a whole lot of benefit to his approach if you're just doing things in 2D and 3D— in those cases, the alternative approaches are in a sense simpler and more straightforward).

Of course, that sort of thing isn't a big deal nowadays, but back then, there was very little abstract, rigorous math out there besides Euclid's system. Perhaps not being brought up in the mathematical mainstream in university made Grassmann a bit clueless about what was expected of him or how people liked to see new mathematical ideas introduced. Besides that, Grassmann had no respected mentor, no famous mathematician to champion his work. When he finally finished his masterwork, Grassmann probably thought the work would surely convince the world that he was a good mathematician and should be allowed to teach math at a University (let alone just the harder high-school level math!). But he was sorely disappointed when he submitted the work in 1947 in an attempt to get a university post and the government asked the famous mathematician Ernst Kummer to give his opinion, and it wasn't very favorable: while he admitted that there were some good ideas in it, he didn't like the way it was presented and recommended against giving Grassmann the position, which effectively killed his chances for good.

As another example of Grassmann not doing a great job of explaining the intuition behind his ideas, he was given a great opportunity by the famous mathematician Möbius in 1946 to enter a competition to develop a geometric calculus that didn't depend at all on coordinates. Grassmann was actually the only one to submit an entry, so he won the competition, but "Möbius, as one of the judges, criticized the way Grassmann introduced abstract notions without giving the reader any intuition as to why those notions were of value." (Source: Wikipedia)

This story would already be pretty sad and disillusioning, but it gets much worse. Grassmann was convinced that his ideas were good, and decided that he just had to do a better job explaining them, making things more rigorous and clearer, and also showing how useful they were. So he spent the next ten years or so writing a bunch of different papers that used his theory for various practical purposes (like "electro dynamics" as it was called then, and problems involving curves and surfaces). Luckily, Grassmann did finally pass his various teaching exams and was able to teach at high schools in various subjects like math, physics, chemistry, and mineralogy, and when his father died, he eventually got to take over his old job in 1852. He was also pretty busy at home, considering that he had eleven kids (seven of whom survived to adulthood), so it's not like he just stayed in his room by himself working.

But he was definitely still an outsider in the rarefied circles of professional mathematics, and he didn't want to be stuck on the outside, so he kept refining and polishing his ideas from his first book. In fact, he worked at it for a ridiculously long time, and in 1862, a full 18 years after the publication of his first book, he finally published his refined second version of the same basic ideas, but in a new presentation, which he called Die Ausdehnungslehre: Vollständig und in strenger Form bearbeitet (link). Surely, this time people would finally recognize his brilliant work, right? No, it was a disaster. No one cared, hardly any copies sold, and he continued in complete obscurity. It's ironic too, since the second book looks basically like how a modern day math textbook would present these ideas, whereas most math books published back then would be pretty inscrutable by contemporary standards of presentation and rigor.

To add insult to injury, Grassmann got a letter from his publisher a couple years after his second book was published that said (in translation): “Your book Die Ausdehnungslehre has been out of print for some time. Since your work hardly sold at all, roughly 600 copies were used in 1864 as waste paper and the remaining few odd copies have now been sold out, with the exception of the one copy in our library.” (Source: Wikipedia). Grassmann was so upset by the way he was ignored after his second book came out that he could no longer pretend that it was just how his ideas were presented that was the problem.

So, he basically gave up. He stopped talking to other mathematicians and stopped working on mathematical ideas, since what was the point if no one read what he wrote or engaged at all with his ideas? Instead, he started studying linguistics and wrote a book about Sanskrit, including a 2,000 page Sanskrit dictionary and translation of the Rigveda which is still cited and read. While learning about Sanskrit, and remembering his university work in Greek, Grassmann noticed a phonological rule that is now known as Grassmann's law. Ironically, it only took a short while for the community of linguists, who are apparently less judgemental and cliquey than mathematicians were back then, to respect and honor him with awards and honorary degrees.

So what ended up happening to his mathematical works? Well, as usually happens, the world finally caught up many decades later and realized that the ideas were extremely smart and powerful. In the last year of Grassmann's life, the great scientist Gibbs discovered his work, and shortly thereafter, his ideas were taken up enthusiastically by Clifford who developed them more fully despite his own tragically short life (he died at just 33 years old).

People started talking about what we now call vector spaces and linear operators in the 1920s, but these ideas had already been nearly fully developed by Grassmann in the 1830's, nearly 100 years before! He didn't publish them until 1844, but that's because he spent a lot of time trying to polish everything nicely so people would understand it better. Anyway, by the 20th century, important mathematicians such as Peano and Cartan (and before that, the great Felix Klein) started talking about how great and ahead of his time Grassmann had been, but unfortunately, Grassmann was long dead by that point, having died in 1877 at the age of 68.

Grassmann's ideas finally won, and there are whole subjects of math today, like differential geometry (and associated applications in theoretical physics, such as general relativity, electromagnetism, and fluid dynamics), that are couched entirely in Grassmann's conceptual framework, at least at the more advanced levels. We truly live in a Grassmannian world. If you had met Grassmann as a teenager, that would probably have come as a massive surprise, as this passage from a 1917 article explains:

"For in 1831 he wrote an account of his life in Latin in connection with the examination for his teacher's certificate; and later, in 1834, he handed in an autobiography to the Konsistorium in Stettin when he was passing his first theological examination. He refers to those earlier years as a period of slumber, his life being filled for the most part with idle reveries in which he himself occupied the central place. He says that he seemed incapable of mental application, and mentions especially his weakness of memory. He relates that his father used to say he would be contented if his son Hermann would be a gardener or artisan of some kind, provided he took up work he was fitted for and that he pursued it with honor and advantage to his fellow men." (Source: The Monist)

Did Grassmann ever in his wildest dreams imagine that this would eventually come to pass? Surprisingly, despite his treatment by his contemporaries, he actually did! Perhaps that explains why he was willing to toil on his own for so long. Here is what he said about this:

“For I have every confidence that the effort I have applied to the science reported upon here, which has occupied a considerable span of my lifetime and demanded the most intense exertions of my powers, is not to be lost. … a time will come when it will be drawn forth from the dust of oblivion and the ideas laid down here will bear fruit. … some day these ideas, even if in an altered form, will reappear and with the passage of time will participate in a lively intellectual exchange. For truth is eternal, it is divine; and no phase in the development of truth, however small the domain it embraces, can pass away without a trace. It remains even if the garments in which feeble men clothe it fall into dust.” — Hermann Grassmann, in the foreword to the Ausdehnungslehre of 1862, translated by Lloyd Kannenberg (Source: GrassmannAlgebra.com)

So, besides being a pretty depressing story about a man who never got the recognition he deserved during his own lifetime, what can the reader of today take away from his story that is a useful generalization? Well, I think there are actually quite a few lessons one can profitably take away from his story:

-

Ideas are important, but they aren't everything. You also need to do a good job explaining your ideas to the world. And if you want the world to care, you need to do so in a way that actually makes sense to people, and in a way that shows them how it might be worth their while to work through the difficulties in understanding your new ideas— because it will allow them to do various new useful things and understand other subjects in useful new ways.

-

Abstraction and generality are great, and that is of course the direction math has gone in a big way up through the present. But you probably shouldn't jump right into the full generality. Instead, start with the simpler cases that are more tangible and intuitive and develop those. That is, start with 2D and 3D, don't start with N-D!

-

Appeal to intuition first if you want to be understood. It's impossible to develop intuition when dealing in N-dimensions, and especially in a subject like geometry, where our intuitions about the subject can be incredibly fruitful in coming up with new theorems and understanding. And those intuitions are, for better or worse, grounded in our corporeal reality as 3D beings in a 3D world. You are wasting your great ideas if you don't first discuss how they work and apply in a more tangible and intuitive setting. Then, once you have your audience hooked, you can explain how the ideas actually generalize completely.

- Part of the problem of this approach for Grassmann's work in particular is that his methods don't really give you much benefit in 2- and 3-dimensions versus the more traditional approach, particularly in practical applications like engineering, where the typical vector/matrix formulation works very well and is more intuitive.

-

If you're an outsider to a field, rather than focus all your energy on getting the messaging/explanation more rigorous and perfect, or even trying to show how your new ideas in the field can be profitably employed in various applications, you're probably better served trying to find just one well-respected insider to that field and win that one person over completely to the merits of your ideas. Then, that person can serve as your champion, and other important and respected thinkers in that field— who are always extremely busy and don't have unlimited bandwidth to decipher long, impenetrable treatises and mathematical monographs— will have much more of a reason to give your ideas serious consideration; you effectively can piggyback on the accumulated credibility of your mentor.

-

If people are telling you that your ideas aren't bad, but they should be expressed in a different/better way, maybe take that feedback more seriously, especially if the people who are giving you that feedback are themselves greatly respected and important in your field. Grassmann heard first from Kummer and then from Möbius that he was presenting his work in a really confusing and un-intuitive way, but he never really took that advice to heart and tried to integrate it into his work. He just doubled down on the rigor and generality, and tried to also include some practical applications, and it didn't work. An important addendum to this point is that, if the experts are ALSO telling you that your ideas themselves are terrible or make no sense, that is a very different situation. The experts might be wrong, and sometimes are, but in most cases it's more likely that you're a crank/charlatan yourself!

- While it's impossible to say how much his failure to make an impact during the time he was doing this work was a result of more "sociological" factors (i.e., him being an outsider in the world of pure math without the imprimatur of a university position), it certainly didn't help that he kept getting that feedback from his peers (at least the ones that even bothered to look at his work, which was a small group to start with).

-

If, despite your best efforts and work product, you are being ignored by your chosen field for whatever reason, try diversifying a bit! How much grimmer would Grassmann's life have been if he hadn't at least won the accolades from his fellow linguists? Some disciplines are simply less snobbish and care less about the provenance and specific presentation of ideas, and care more about what new things they can do or understand using those ideas. If you are truly "casting pearls before swine," then maybe the best thing to do is find a new audience to cast things before!

-

If you have the talent and proclivity, maybe you should major in math/physics/etc. rather than a softer subject like religion. It's much easier to learn the formal subjects in the structured environment of a university. Even if you're interested and talented in the humanities (or theology, philology, whatever), you can much more readily study those subjects on your own after school. Not only will you learn the math on firmer ground, you'll also be inculcated by the mores and customs of that field, and emerge with a much better idea of the way you should pitch your work to that community. Or maybe not— maybe Grassmann only came up with his super innovative work because he didn't study math in the same way as everyone else, but instead tried to figure it all out on his own, using his totally original approach and conceptualizations. But it certainly didn't help him spread those ideas, which is half the battle if you want to live a satisfying professional life in your chosen field.

While learning more about Grassmann and exterior algebras (not that I'm even slightly an expert on the subject), I couldn't help getting the feeling that there were some real parallels to other disciplines, and particularly to computer programming. I'll try to explain what I mean here. First, I would point out again something I mentioned earlier: that, from a practical computational standpoint for engineering and applied math/physics, the presentation of linear algebra in terms of Grassmann-style exterior algebra and wedge products and bivectors doesn’t really help much, because it doesn’t let you calculate anything that can’t be readily calculated by more direct and less abstract methods using the more typical "introductory presentation" of linear algebra in terms of vectors, matrices, determinants, etc. This traditional approach is typically sufficient for most engineering applications and allows for direct calculation of quantities such as:

-

Solving systems of linear equations (using matrix methods like Gaussian elimination, LU decomposition, or the matrix inverse).

-

Applying linear transformations, rotations, and scaling using matrices.

-

Calculating eigenvalues and eigenvectors for stability analysis, vibration modes, and other applications.

-

Determining areas, volumes, and solving linear systems using determinants.

Where the Grassmann approach starts to really shine is when you're dealing with more complex ideas, like trying to represent multi-dimensional volumes, orientations, and intersections, which can be cumbersome with traditional matrix methods, or when you move to higher dimensions, where exterior algebra naturally extends to multilinear algebra, allowing for the manipulation of tensors and forms in a way that generalizes concepts from linear algebra.

It's important to point out that the Grassmann approach doesn't really let you do anything that's not possible to do using traditional matrix approaches and the generalizations to tensors (which are basically matrices of matrices). It's more that they offer a different and very useful perspective and way of dealing with these ideas that has a lot of theoretical power, especially when you go beyond the basic stuff and get to the deeper mathematical ideas surrounding things like symmetry and invariants under transformations— the sort of "big ideas" that help unify and give structure to the subject in the minds of mathematicians and give a good conceptual framework for thinking about problems.

So how does all this relate to computer programming? Well, in a sense, can you think of these two approaches— on the one hand, matrices and tensors with the usual language and methods for working with them, and on the other hand, bivectors and wedge products and the Grassmann approach and presentation— as being a matter of "where you put the abstractions" of the underlying structure you’re working with. That is, with the matrix/tensor approach, the complexity and abstraction is in the underlying data structure itself— in the matrix or tensor and its structure— and then the operations for working with this data are relatively simple, like taking dot products or matrix multiplication. Whereas with the Grassmann approach, you're putting more of the complexity and structure in the operations themselves and less in the data structures. I'll try to flesh out what I mean a bit more here:

-

Data Complexity:

- In the matrix and tensor approach, the complexity is primarily in the structure of the data itself. Matrices and tensors are multi-dimensional arrays that can represent a wide range of relationships and data configurations.

- Each entry in a matrix or tensor can have a different meaning depending on its position, and higher-order tensors can represent complex multi-dimensional relationships.

-

Operations:

- The operations on matrices and tensors, such as addition, multiplication, and contraction, are relatively straightforward and well-defined.

- These operations extend naturally from lower-dimensional cases (e.g., vector and matrix operations) to higher dimensions without fundamentally changing their nature.

-

Example:

- A matrix multiplication is a clear and direct operation that combines rows and columns of matrices to produce another matrix. The operation itself is simple and systematic, but the matrix structure can encode complex transformations and relationships.

-

Data Simplicity:

- In Grassmann’s approach, the data elements themselves (vectors, scalars, bivectors, etc.) are simpler and more elemental. They represent basic geometric objects and their orientations.

- The complexity and richness of the structure come from the operations applied to these elements, such as the wedge product.

-

Operations:

- The wedge product and other operations in exterior algebra encapsulate more of the abstraction and complexity. These operations introduce antisymmetry and higher-dimensional relationships in a natural and unified way.

- The operations themselves are more abstract, but they allow for elegant and compact representations of complex geometric and algebraic relationships.

-

Example:

- The wedge product of two vectors produces a bivector, representing the oriented area spanned by the vectors. This operation abstracts the orientation and area into a single algebraic object, simplifying the representation of such relationships.

-

Matrix/Tensor Approach:

- Complexity in Data: Matrices and tensors encapsulate complex structures within their entries and indices.

- Simplicity in Operations: The operations on these data structures are direct and extend naturally from familiar concepts like vector addition and scalar multiplication.

-

Grassmann’s Approach:

- Simplicity in Data: The data elements (vectors, scalars, bivectors) are simpler and more foundational.

- Complexity in Operations: The operations (wedge product, Hodge dual) are where the complexity and abstraction lie, capturing relationships and interactions in a sophisticated way.

-

Engineering and Applied Sciences:

- The matrix/tensor approach is often more practical for engineering and applied sciences because it provides a straightforward framework for numerical computation and data manipulation.

- Software tools and numerical libraries are well-optimized for matrix and tensor operations, making them efficient and easy to use for practical applications.

-

Theoretical and Abstract Mathematics:

- Grassmann’s approach shines in theoretical contexts where the relationships and interactions between geometric objects are of primary importance.

- Exterior algebra and wedge products provide a powerful language for expressing these relationships concisely and elegantly, which is valuable in fields like differential geometry, algebraic topology, and theoretical physics.

Now, the connection I saw to computer programming should hopefully be much clearer to you! In computer programming, you can often solve your problem mostly by choosing the right data structure which fits your problem nicely and leads to simple and performant code for computing with those data structures. Or, you can just use any old simple data structure like a linked list, and then your code becomes more complex and harder to optimize, but because you are ultimately dealing with very simple data structures at the "atomic" level, it is in some sense easier to understand each individual step and the "transformative essence" of the computation.

As you can probably tell, I and many other programmers have a very strong preference for the data structure centric approach. I find it a lot easier to think about various calculations if they can be easily conceptualized with a particular data structure. For example, the humble 2D table of rows and columns of data, like in Excel or Pandas, is an incredibly useful and powerful conceptual tool for doing all sorts of very complex transformations to data. Things like windowed averages over various lookback windows, or complex aggregate functions, can be done very quickly and easily, because you can essentially lean on the underlying structure and layout of the data itself to offload some of the complexity. And if you're trying to make an ACID compliant database, picking a B-tree as your fundamental primitive is going to make things a lot simpler because it will automatically take care of lots of issues that would otherwise require complicated strategies to deal with.

All that is to say, it doesn't really surprise me that vectors/matrices/tensors "won." The kinds of problems that most engineers and scientists care about, whether it's an engineer trying to calculate the forces and vibration modes of a trussed structure like a bridge, or a physicist trying to understand the spectrum emitted by a certain material when stimulated by light, usually come down to some variant of "gather together all the relevant data for your problem and arrange it in the form of a matrix, preferably a symmetric matrix; then compute the eigen-decomposition of that system and your desired answer should just fall out."

We see that pattern over and over again in so many disciplines that it's almost hard to believe that the same basic approach could keep working so well in such diverse settings. To give just a partial listing of such ideas in different disciplines:

-

Structural Engineering:

- Modal Analysis: In structural engineering, modal analysis is used to determine the natural vibration modes of structures such as bridges, buildings, and mechanical components. The mass and stiffness matrices of the structure are used to solve the eigenvalue problem, where the eigenvalues represent the natural frequencies and the eigenvectors represent the corresponding mode shapes.

- Stability Analysis: In stability analysis of structures, eigenvalue problems are solved to determine the critical load at which a structure becomes unstable (buckles). The stiffness matrix and geometric stiffness matrix are used to form a generalized eigenvalue problem.

-

Acoustics:

- Room Acoustics: In acoustics, the eigenmodes of a room or enclosure are determined by solving the Helmholtz equation. The eigenvalues correspond to the resonant frequencies, and the eigenvectors describe the spatial distribution of the sound pressure levels.

- Vibration Analysis: For acoustic systems like musical instruments or loudspeakers, the eigenmodes of the vibrating surfaces are analyzed to understand their frequency response and sound radiation characteristics.

-

Control Systems:

- State-Space Analysis: In control engineering, the dynamics of a system are often represented in state-space form. The system's behavior can be analyzed by computing the eigenvalues of the system matrix, which indicate the stability and response characteristics of the system.

- Pole Placement: Designing controllers involves placing the poles of the closed-loop system at desired locations in the complex plane. This is achieved by manipulating the eigenvalues of the system matrix.

-

Electrical Engineering:

- Power System Stability: In power systems, the stability of the network can be assessed by forming the admittance matrix and computing its eigenvalues. The eigenvalues provide insights into the stability margins and dynamic behavior of the power grid.

- Signal Processing: Eigen decomposition is used in various signal processing techniques, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, noise reduction, and feature extraction.

-

Computer Graphics and Vision:

- Shape Analysis: In computer graphics and vision, the shape of 3D objects can be analyzed by constructing matrices such as the Laplacian matrix and computing their eigenvalues and eigenvectors. These eigenmodes are used for tasks like mesh smoothing, segmentation, and deformation.

- Image Compression: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) are used for image compression and feature extraction by approximating the original image with fewer principal components.

-

Network Analysis:

- PageRank Algorithm: The PageRank algorithm used by Google to rank web pages constructs a stochastic matrix representing the web graph and computes its dominant eigenvector, which corresponds to the steady-state distribution of the random surfer model.

- Community Detection: In social network analysis, spectral clustering is used to detect communities by constructing a graph Laplacian matrix and analyzing its eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

-

Quantum Mechanics:

- Quantum State Analysis: In quantum mechanics, the properties of quantum systems are often analyzed by solving the Schrödinger equation. The Hamiltonian matrix is diagonalized to obtain its eigenvalues and eigenvectors, which correspond to the energy levels and quantum states of the system.

Basically, matrices are really great data structures for encoding useful things about the world. If you need some concept of physical locality, like pixels in an image that are nearby each other in 2D tending to be similar in color and brightness, that's built in— you don't need to somehow tack it on as you might if you were dealing with all the pixels as a linked list. Once you've managed to express your problem in the form of a matrix, the math "doesn't care" what it represents anymore: it's just a matrix and you now have access to all the many tools and concepts from linear algebra to do stuff with that matrix. For practical, real world problems, matrices usually are the way to go.

But at the same time, it's not as clear that scientists would have been able to come up with the deep insights that are embodied in General Relativity or the current Standard Model of physics if they were just dealing with things at the level of vectors, matrices, and tensors. Again, I'm not saying that it would be impossible to do so, because of course the formulations are essentially the same at an intrinsic level; it's more that I suspect that the Grassmannian approach highlights certain aspects of these subjects in a way that somehow make it easier for theorists to conceptualize the deepest nature of the subjects— things like invariants and symmetries that can give the sudden "aha!" moments that crack a field wide open and enable new problems to be solved.

If you're like me, you'll probably want to learn more about Grassmann's unusual life. Besides the Wikipedia article linked to at the start of this essay, I found this site to have a lot of interesting details about Grassmann's work. Also, there are a few more detailed scholarly works about his life, such as the ones here and here. There is also a longer and more recent book-length biography that can be found here.