This repository contains a Proof-of-Concept code, as well as the code walkthrough of a client-driver code which retrieves a handle to any process using a kernel driver. Usually, userland code can request a handle of a process using the OpenProcess() function, but it may fail in the case of certain processes like protected/privileged processes. However, no such restrictions are present in the Kernel Land.

In this case, the client takes in a target process's PID and tries to open a handle to it with PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS permissions using the OpenProcess() function. In case that fails, we then make a call to our driver using DeviceIoControl() to retrieve a handle from kernel land.

This repository is a part of my ongoing attempt to document my journey into Windows Kernel Land. I recommend reading through the previous post first in case you haven't already as I will skip some sections of the code which have been previously discussed back there.

.\ProcessRevealClient <PID>

The code consists of two parts a client and a driver. We would first look at the Driver code and then the client code.

The Driver has the following functions:

DriverEntry()- Driver entry point functionProcRevealUnload()- This function is called when the system unloads our driverProcRevealCreateClose()- This function handles Create/Close dispatch routines issued by the ClientProcRevealDeviceControl()- This function handles the DeviceControl dispatch routines issued by the Client

I am going to speedrun through these functions as they are almost the same as last time.

Just like before we fill the major function array entries with the associated functions responsible for handling the respective dispatch routines. Then we create a Kernel device using IoCreateDevice(). Clients will be interacting with this device object. Finally, we create a symlink pointing to that device with IoCreateSymbolicLink(). That's it.

This function is responsible for handling all Create and Close dispatch routines. This is a good time to introduce the CompleteRequest() function - which is just a convenience function we have so that we don't have to write the same repetitive code to complete IRPs.

This function is called when the driver is unloaded by the system. It performs the necessary cleanups like deleting the Device object we previously created as well as the corresponding symlink.

This function is responsible for handling any Device Control dispatch requests. The code function looks like this:

NTSTATUS ProcRevealDeviceControl(PDEVICE_OBJECT _DeviceObject, PIRP Irp) {

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(_DeviceObject);

ULONG len = 0;

NTSTATUS status = STATUS_INVALID_DEVICE_REQUEST;

PIO_STACK_LOCATION irpSp = IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation(Irp);

switch (irpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.IoControlCode) {

case IOCTL_OPEN_PROCESS:

// Check size of input and output buffer sizes

if (irpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.InputBufferLength < sizeof(ProcessData) ||

irpSp->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.OutputBufferLength < sizeof(HANDLE)) {

status = STATUS_BUFFER_TOO_SMALL;

break;

}

// Get process data sent by client

ProcessData* cData = (ProcessData*)Irp->AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer;

if (NULL == cData) {

status = STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER;

break;

}

CLIENT_ID cid = { 0 };

cid.UniqueProcess = ULongToHandle(cData->ProcessId);

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES objAttr = RTL_CONSTANT_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES(NULL, 0);

HANDLE hProcess;

status = ZwOpenProcess(&hProcess, cData->Access, &objAttr, &cid);

if (NT_SUCCESS(status)) {

len = sizeof(HANDLE);

KdPrint((DRIVER_PREFIX "Escalated Handle:\t0x%p\n", hProcess));

memcpy(cData, &hProcess, sizeof(hProcess));

}

break;

}

return CompleteRequest(Irp, status, len);

}The first thing we need to understand before diving into the function is the idea of Control Codes. According to MSDN:

I/O control codes (IOCTLs) are used for communication between user-mode applications and drivers, or for communication internally among drivers in a stack. I/O control codes are sent using IRPs.

These codes help the driver to define the functionality that the client seeks out of it. For example, a dispatch routine can have functionality to support various control codes, each of which caters to a specific condition.

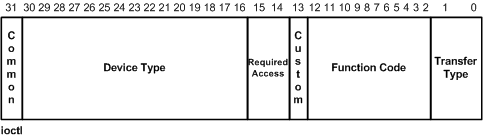

For example, our driver uses just one control code - IOCTL_OPEN_PROCESS. This cannot be an arbitrary number. There is a very specific way of constructing a Control Code. An I/O control code is a 32-bit value that consists of several fields. The following figure illustrates the layout of I/O control codes:

Windows makes it easier for us to define a control code using the CTL_CODE macro, which expands to:

#define CTL_CODE( DeviceType, Function, Method, Access ) ( \

((DeviceType) << 16) | ((Access) << 14) | ((Function) << 2) | (Method) \

)This Microsoft article goes through the details of defining I/O Control Codes. Just to give a quick rundown,

- DeviceType: This value identifies the device type and must be greater than or equal to 0x8000 because values lower than that are reserved for Microsoft.

- Function: This value identifies the function to be performed by the driver and must be higher than or equal to 0x800.

- Method: Indicates how the system will pass data between the Client and the Driver, essentially the Buffer Descriptions to go along with the IOCTL. More on this later.

- Access - Indicates the type of access that a caller must request when opening the file object that represents the device. This can be

FILE_ANY_ACCESS,FILE_READ_DATA, orFILE_WRITE_DATA- the last two of which can be ORed together.

For our case, we define IOCTL_OPEN_PROCESS as:

#define IOCTL_OPEN_PROCESS CTL_CODE(0x8001, 0x801, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)We set DeviceType to a value just above 0x8000, and the Function code to a value just over 0x800. For the Access type, we choose FILE_ANY_ACCESS to avoid any unwanted access issues. Finally coming to the Method parameter which is set to METHOD_BUFFERED. This allows us to use Buffered I/O with our driver. Looking at the description coming from Microsoft:

For this transfer type, IRPs supply a pointer to a buffer at Irp->AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer. This buffer represents both the input buffer and the output buffer that is specified in calls to DeviceIoControl and IoBuildDeviceIoControlRequest. The driver transfers data out of, and then into, this buffer.

For input data, the buffer size is specified by Parameters.DeviceIoControl.InputBufferLength in the driver's IO_STACK_LOCATION structure. For output data, the buffer size is specified by Parameters.DeviceIoControl.OutputBufferLength in the driver's IO_STACK_LOCATION structure.

The size of the space that the system allocates for the single input/output buffer is the larger of the two length values.

Essentially, when using Buffered I/O the IO manager copies the user buffer into a memory region that can be safely accessed by the kernel, and once the operations are done, it copies it back to the user's memory space.

Now that we have this out of the way, we can take a look at the driver code. Once we have the current IRP stack location, we check the Parameters.DeviceIoControl.IoControlCode member to check the control code issued by the client. Here we have just one control code, so we check for it. If the control code matches - we first check if we have the right buffer sizes. We use the ProcRevealCommon.h header file to define the common units used by both the client and driver, and in there we define the ProcessData struct, which is used to pass information to the driver.

typedef struct _ProcessData {

ULONG ProcessId;

ACCESS_MASK Access;

} ProcessData;If the buffer lengths are okay, we then map the AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer to a ProcessData struct. The AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer is where the I/O Manager copies the user-supplied buffer to make it accessible to the Driver, and mapping it to the structure allows us to easily access it.

Moving on - the crux of the program lies in the ZwOpenProcess() function - which does the heavy lifting for us. Consider it analogous to the OpenProcess() function(to be more accurate, it's the kernel counterpart to NtOpenProcess()) - but with Kernel powers.

The ZwOpenProcess() function takes the following parameters:

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

[out] PHANDLE ProcessHandle |

&hProcess |

A pointer to a HANDLE. The ZwOpenProcess routine writes the process handle to the variable that this parameter points to. |

[in] ACCESS_MASK DesiredAcces |

cData->Access |

The access right to the process project which the client requests |

[in] POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes, |

&objAttr |

Pointer to an OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES structure that specifies the attributes to apply to the process object handle. More on this later |

[in, optional] PCLIENT_ID ClientId |

&cid |

A pointer to a client ID that identifies the thread whose process is to be opened. |

There are two parts which I want to touch upon first:

-

PCLIENT_ID: Pointer to a structure contains identifiers of a process and a thread. For our case, we zero out the initial structure, and then set theUniqueProcessprocess, which should point to the Process ID. However, theUniqueProcessparameter takes aHANDLEinstead of aULONG, so we use theULongToHandle()function to make that conversion. -

POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES- A pointer to a structure that specifies the project object's attributes. This is usually used to set the Security Descriptor for the process handle, but since we have no special requirements like that, we would be zero-ing it all. The documentation forZwOpenProcess()states that:The ObjectName field of this structure must be set to NULL.

So, we can always do something like:

InitializeObjectAttributes(&objAttr, NULL, 0, NULL, NULL);

But, we have an easier way of doing it with the

RTL_CONSTANT_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES()macro which expands to:#define RTL_CONSTANT_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES(n, a) { sizeof(OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES), NULL, n, a, NULL, NULL }

Once, these parameters are initialized and if the call to ZwOpenProcess() is successful, we copy the value of the handle to the shared buffer space. Note that in Buffered I/O, the input and output share the same buffer, so, we will be copying the handle to the save memory we previously mapped the ProcessData struct from.

With the handle value copied, we can go ahead and complete the Irp using the CompleteRequest() helper function we talked about earlier.

With that done, we are now done with the driver and can move safely to the client side of the code.

Coming to the client code, this is what a barebones version of the code looks like:

int main(int argc, char * argv[]) {

char* __t;

HANDLE hProcess;

DWORD bytes = 0;

ProcessData data = { 0 };

if (argc != 2) return -1;

ULONG pid = strtoul(argv[1], &__t, 10);

hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, pid);

if (hProcess != NULL) {

CloseHandle(hProcess);

return 1;

}

HANDLE hDevice = CreateFile(USER_DEVICE_SYM_LINK, GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

data.ProcessId = pid;

data.Access = PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS;

DeviceIoControl(hDevice, IOCTL_OPEN_PROCESS, &data, sizeof(data), &hProcess, sizeof(hProcess), &bytes, NULL);

CloseHandle(hDevice);

CloseHandle(hProcess);

}The client checks for the correct user-supplied Process ID, converts it into a ULONG, and then tries to open a handle using OpenProcess() and in case it fails (which we are expecting it to), we move on opening a handle to our device object, using CreateFile() (read the previous article for details). Then we set the specify the target pid and the desired access right in the ProcessData struct.

Finally, we call the DeviceIoControl() function - the hero of the show. The parameters of the function are as follows:

| Variable | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

[in] HANDLE hDevice |

hDevice |

Handle to the kernel device object |

[in] DWORD dwIoControlCode |

IOCTL_OPEN_PROCESS |

The I/O control code for the operation |

[in, optional] LPVOID lpInBuffer |

&data |

Pointer to the input buffer, aka a ProcessData struct which contains the user-specified options |

[in] DWORD nInBufferSize |

sizeof(data) |

The size of the input buffer |

[out, optional] LPVOID lpOutBuffer |

&hProcess |

A pointer to the output buffer which is to receive the handle |

[in] nOutBufferSize |

sizeof(hProcess) |

Size of output buffer |

[out, optional] LPDWORD lpBytesReturned |

&bytes |

A pointer to a variable that receives the size of the data stored in the output buffer, in bytes |

[in, out, optional] LPOVERLAPPED lpOverlapped |

NULL |

A pointer to an OVERLAPPED structure, something we don't need right now |

If the call to DeviceIoControl() succeeds, we should have a handle to the process with PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS permissions!

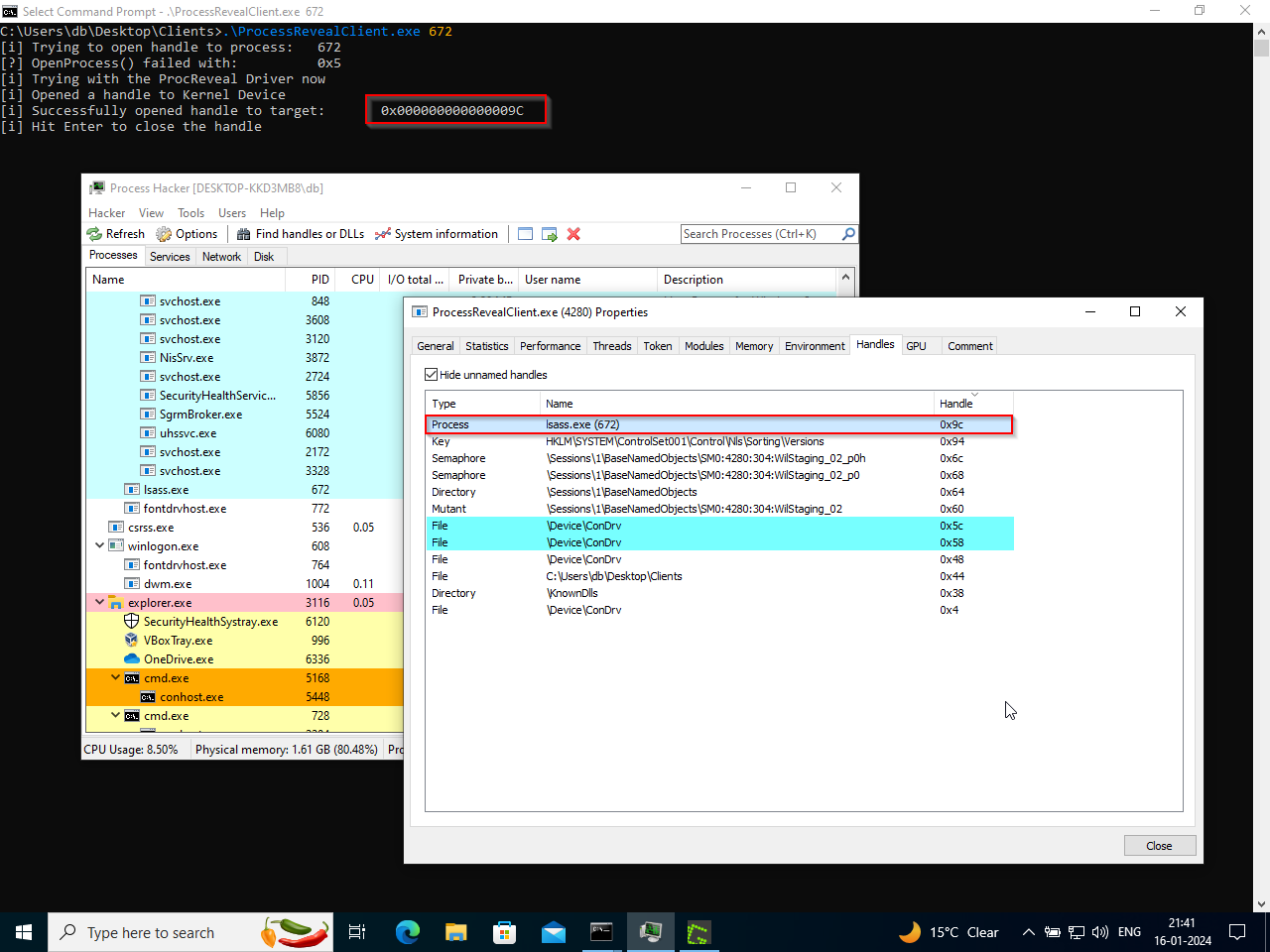

First, we use the sc.exe command line utility to load and start the driver. Once the driver has been loaded and is up and running, we can use the client to get a handle on a protected process - let's say lsass.exe.

We see that the initial OpenProcess() calls failed with the error code 0x5 aka ERROR_ACCESS_DENIED as expected because lsass.exe is a protected process after all. Once this fails, the client uses the Kernel device to get a handle on the process. Since there is nothing called a Protected Process from the Kernel Land (loosely speaking), we can get a handle on the process.

Just to verify this, we can always open up Process Hacker and examine the Handles tab of the Client Program, and there we should see the handle to the process being reflected there, indicating that our program works as expected!

With that, we complete another code walkthrough of the series. In case you haven't been following along, here are the previous ones, in order:

That being said, congratulations if you made it this far, and thanks for reading it through! This blog post is a part of my efforts to document my journey into Windows Kernel Land while going through @zodicon's Windows Internal training. Feel free to reach out to me with any feedback - and follow my Github/LinkedIn for more updates in the future. Till next time - Happy Hacking 🎉

This article is directly influenced by @zodicon's Windows Internal training and I recommend everyone interested in Windows Kernel Development to check it out.