This is a Keras implementation of the SSD model architecture introduced by Wei Liu at al. in the paper SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector.

The main goal of this project is to create an SSD implementation that is well documented for those who are interested in a low-level understanding of the model. The documentation and detailed comments hopefully make it a bit easier to dig into the code and adapt or build upon the model than with most other implementations out there (Keras or otherwise) that provide little to no documentation and comments.

Fully trained, convolutionalized VGG-16 weights are provided below, but fully trained SSD models are not.

There are currently two base network architectures in this repository. The first one, keras_ssd300.py, is a port of the original SSD300 architecture that is based on a reduced atrous VGG-16 as described in the paper. The network architecture and all default parameter settings were taken directly from the .prototxt files of the original Caffe implementation. The other, keras_ssd7.py, is a smaller 7-layer version that can be trained from scratch relatively quickly even on a mid-tier GPU, yet is capable enough to do an OK job on Pascal VOC and a surprisingly good job on datasets with only a few object categories. Of course you're not going to get state-of-the-art results with that one.

If you want to build an arbitrary SSD model architecture, you can use keras_ssd7.py as a template. It provides documentation and comments to help you turn it into a deeper network relatively easily.

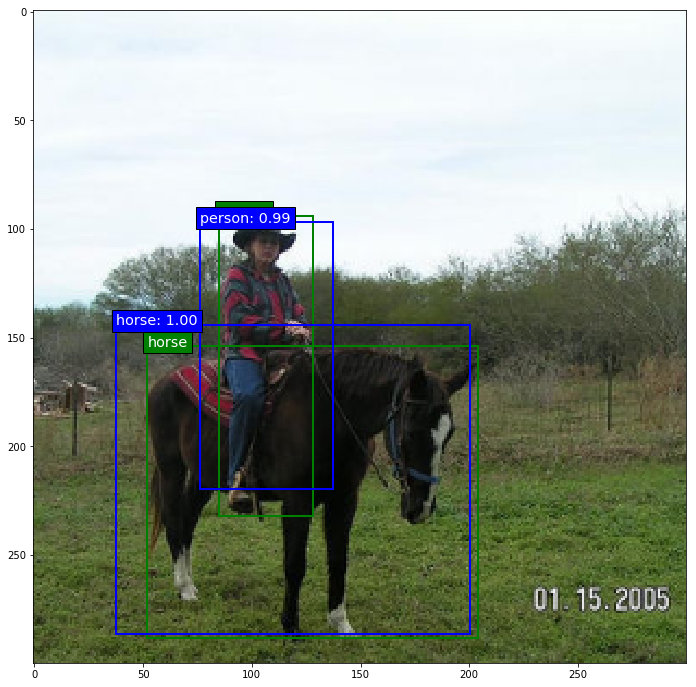

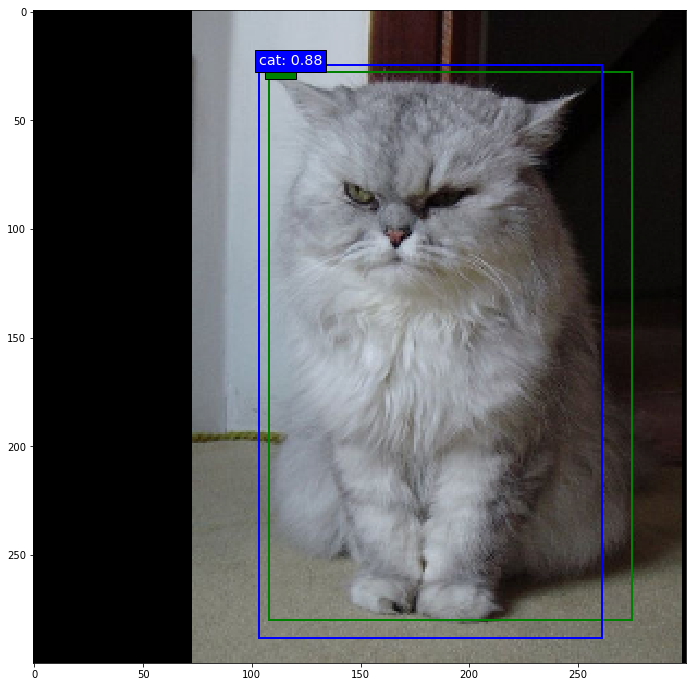

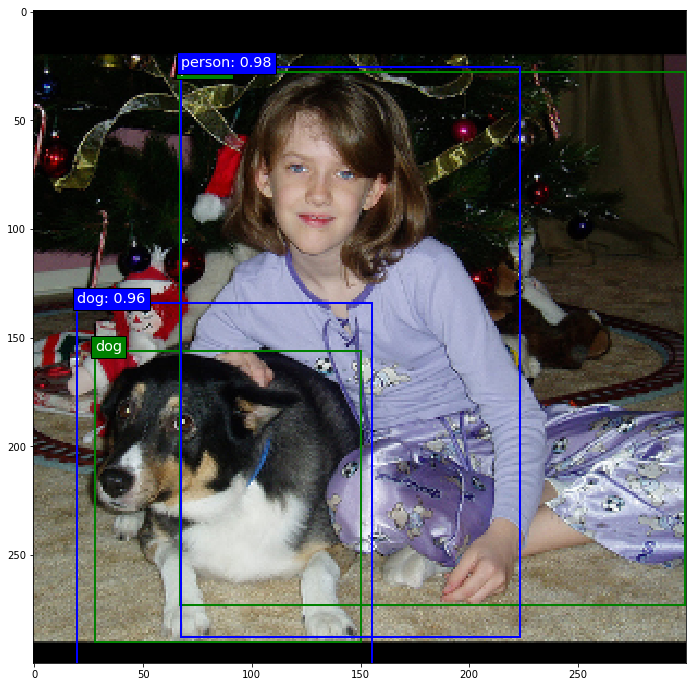

Below are some prediction examples of an SSD300 partially trained (20,000 steps at batch size 32) on Pascal VOC2007 trainval, VOC2007 test, and VOC2012 train. The predictions were made on VOC2012 val. The purpose of these examples is just to demonstrate that the code works and the model learns. Predictions are shown in blue, ground truth boxes in green.

|

|

|

|

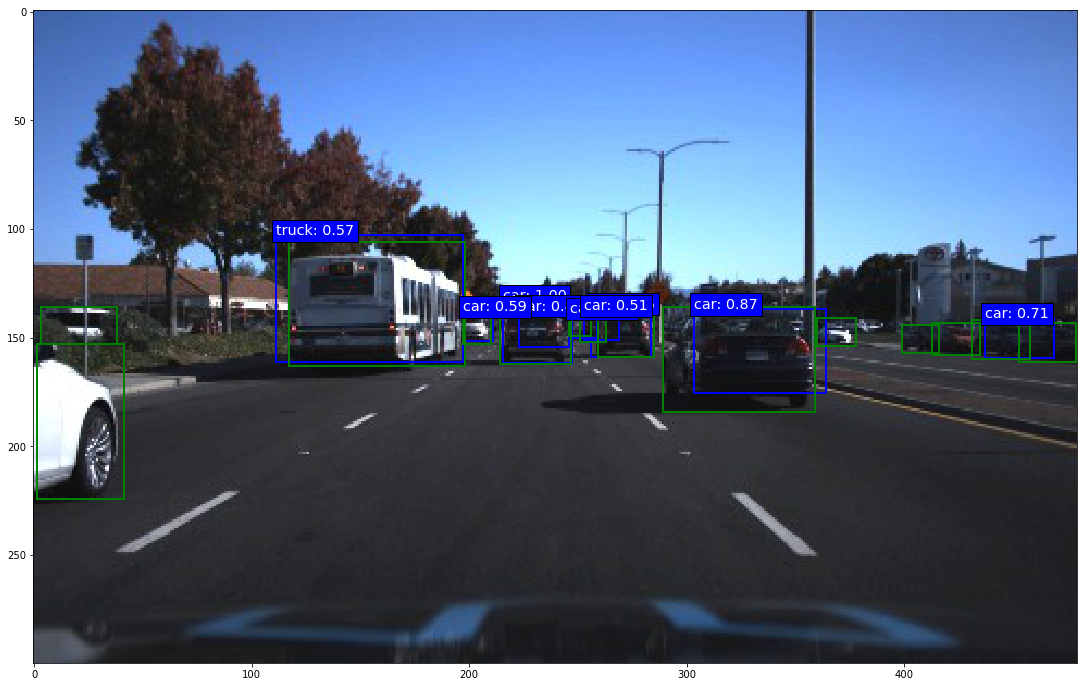

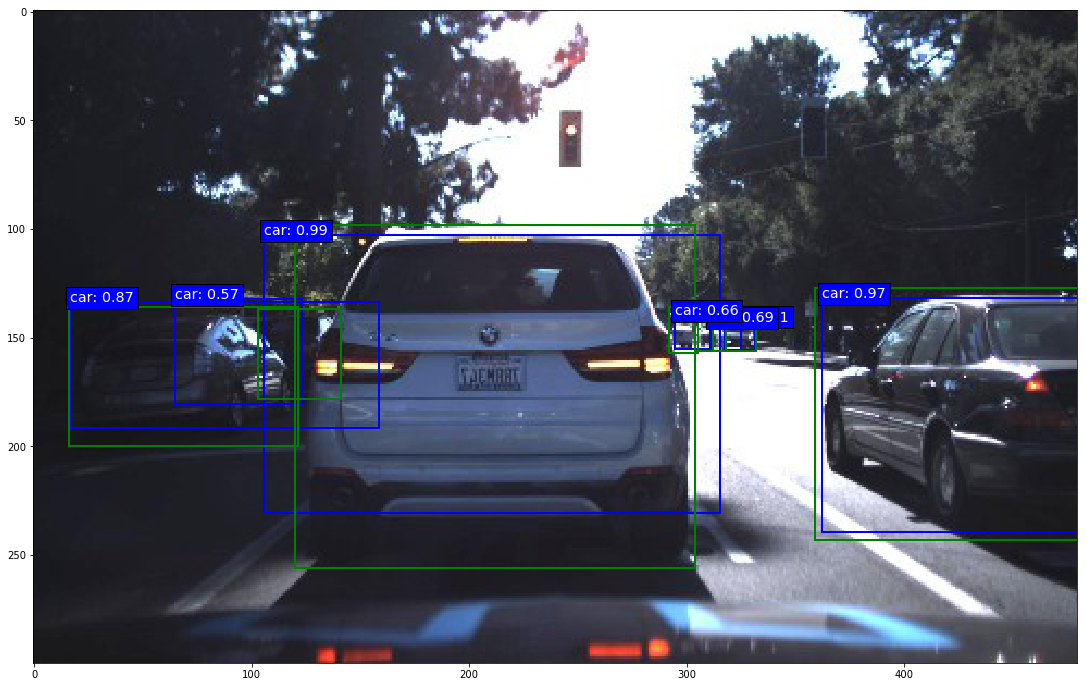

Below are some prediction examples of an SSD7 (i.e. the small 7-layer version) partially trained on two street traffic datasets released by Udacity with roughly 20,000 images in total and 5 object categories (more info in train_ssd7.ipynb). The predictions you see below were made after only 7000 training steps at batch size 32. Admittedly, cars are comparatively easy objects to detect, but it is nonetheless remarkable what such a small model can do after 7000 training iterations.

|

|

|

|

- Python 3.x

- Numpy

- TensorFlow 1.x

- Keras 2.x

- OpenCV (for data augmentation)

- Beautiful Soup 4.x (to parse XML files)

The Theano and CNTK backends are currently not supported.

Clone or download this repository, then:

The general training setup is layed out and explained in train_ssd7.ipynb and in train_ssd300.ipynb. The setup and explanations are similar in both notebooks for the most part, so it doesn't matter which one you look at to understand the general training setup, but the parameters in train_ssd300.ipynb are preset to copy the setup of the original Caffe implementation for training on Pascal VOC, while the parameters in train_ssd7.ipynb are preset to train on the Udacity traffic datasets. If your goal is not to train the original SSD300, then I would recommend reading train_ssd7.ipynb, which contains slightly more general explanations.

To train the original SSD300 model on Pascal VOC, download the datasets:

wget http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/voc2012/VOCtrainval_11-May-2012.tar

wget http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/voc2007/VOCtrainval_06-Nov-2007.tar

wget http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/voc2007/VOCtest_06-Nov-2007.tar

Set the file paths to the data accordingly in train_ssd300.ipynb and execute the cells.

It is also strongly recommended that you load the pre-trained VGG-16 weights linked below when attempting to train SSD300, otherwise your training will almost certainly be unsuccessful. Note that the original VGG-16 was trained layer-wise, so trying to train the even deeper SSD300 all at once from scratch will very likely not work. Also note that even with the pre-trained VGG-16 weights it will take at least 20,000 training steps to get a half-decent performance out of SSD300.

Training and prediction are covered in the notebook, but mAP evaluation is not.

If you'd like to train a model on arbitrary datasets, a brief introduction to the design of the data generator might be useful:

The generator class BatchGenerator is in the module ssd_batch_generator.py and using it consists of three steps:

- Create an instance using the constructor. The constructor just sets the desired order in which the generator yields the ground truth box coordinates and class ID. Even though different box coordinate orders are theoretically possible,

SSDBoxEncodercurrently requires the generator to pass ground truth box coordinates to it in the format[class_id, xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax], which is also the constructor's default setting for this parameter. - Next, lists of image names and annotations (labels, targets, call them whatever you like) need to be parsed from one or multiple source files such as CSV or XML files by calling one of the parser methods that

BatchGeneratorprovides. The generator object stores the data that is later used to generate the batches in two Python lists:filenamesandlabels. The former contains just the file paths of the images to be included, e.g. "some_dataset/001934375.png". The latter contains for each image a Numpy array with the bounding box coordinates and object class ID of each labeled object in the image. The job of the parse methods that the generator provides is to create these two lists.parse_xml()does this for the Pascal VOC data format andparse_csv()does it for any CSV file in which the image names, category IDs and box coordinates make up the first six columns of the file. If you have a dataset that stores its annotations in a format that is not compatible with the two existing parser methods, you can just write an additional parser method that can parse whatever format your annotations are in. As long as that parser method sets the two listsfilenamesandlabelsas described in the documentation, you can use this generator with an arbitrary dataset without having to change anything else. - Finally, in order to actually generate a batch, call the

generate()method. You have to set the desired batch size and whether or not to generate batches in training mode. If batches are generated in training mode,generate()calls theencode_y()method ofSSDBoxEncoderfrom the modulessd_box_encode_decode_utils.pyto convert the ground truth labels into the big tensor that the cost function needs. This is why you need to pass anSSDBoxEncoderinstance togenerate()in training mode. Insideencode_y()is where the anchor box matching and box coordinate conversion happens. If batches are not generated in training mode, then the ground truth labels are just returned in their regular format along with the images. The remaining arguments ofgenerate()are mainly image manipulation features for online data augmentation and to get the images into the size you need. The documentation describes them in detail.

The module ssd_box_encode_decode_utils.py contains all functions and classes related to encoding and decoding boxes. Encoding boxes means converting ground truth labels into the target format that the loss function needs during training. It is this encoding process in which the matching of ground truth boxes to anchor boxes (the paper calls them default boxes and in the original C++ code they are called priors - all the same thing) happens. Decoding boxes means converting raw model output back to the input label format, which entails various conversion and filtering processes such as non-maximum suppression (NMS).

In order to train the model, you need to create an instance of SSDBoxEncoder that needs to be passed to the batch generator. The batch generator does the rest, so you don't usually need to call any of SSDBoxEncoder's methods manually. If you choose to use your own generator, here is very briefly how the SSDBoxEncoder class is set up: In order to produce a tensor for training you only need to call encode_y(), which calls generate_encode_template() to make a template full of anchor boxes, which in turn calls generate_anchor_boxes() to compute the anchor box coordinates for each predictor layer. The matching happens in encode_y().

To decode the raw model output, call either decode_y() or decode_y2(). The former follows the procedure outlined in the paper, which entails doing NMS per object category, the latter is a more efficient alternative that does not distinguish object categories for NMS and I found it also delivers better results. Read the documentation for details about both functions.

A note on the SSDBoxEncoder constructor: The coords argument lets you choose what coordinate format the model should learn. If you choose the 'centroids' format, the targets will be converted to the (cx, cy, w, h) coordinate format used in the original implementation. If you choose the 'minmax' format, the targets will be converted to the coordinate format (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax).

A note on the relative box coordinates used internally by the model: This may or may not be obvious to you, but it is important to understand that it is not possible for the model to predict absolute coordinates for the predicted bounding boxes. In order to be able to predict absolute box coordinates, the convolutional layers responsible for localization would need to produce different output values for the same object instance at different locations within the input image. This is not possible, since for a given input to the filter of a convolutional layer, the filter will produce the same output regardless of the spatial position within the image because of the shared weights. This is the reason why the model predicts offsets to anchor boxes instead of absolute coordinates, and why during training, absolute ground truth coordinates are converted to anchor box offsets in the encoding process. The fact that the model predicts offsets to anchor box coordinates is in turn the reason why the model contains anchor box layers that do nothing but output the anchor box coordinates so that the model's output tensor can include those. If the model's output tensor did not contain the anchor box coordinates, the information to convert the predicted offsets back to absolute coordinates would be missing in the model output.

If you want to build a different base network architecture, you could use keras_ssd7.py as a template. It provides documentation and comments to help you turn it into a deeper network easily. Put together the base network you want and add a predictor layer on top of each network layer from which you would like to make predictions. Create two predictor heads for each, one for localization, one for classification. Create an anchor box layer for each predictor layer and set the respective localization head's output as the input for the anchor box layer. All tensor reshaping and concatenation operations remain the same, you just have to make sure to include all of your predictor and anchor box layers of course.

You can download the weights of the fully convolutionalized VGG-16 model trained to convergence on ImageNet classification here. This is a modified version of the VGG-16 model from keras.applications.vgg16. In particular, the fc6 and fc7 layers were convolutionalized and sub-sampled from depth 4096 to 1024, following the paper.

The following things are still on the to-do list and contributions are welcome:

- Port weights from the original Caffe implementation for the fully trained networks in all configurations (SSD300, SSD512, trained on Pascal VOC, MS COCO etc.)

- Write an mAP evaluation module

- Support the Theano and CNTK backends

- "Anchor boxes": The paper calls them "default boxes", in the original C++ code they are called "prior boxes" or "priors", and the Faster R-CNN paper calls them "anchor boxes". All terms mean the same thing, but I slightly prefer the name "anchor boxes" because I find it to be the most descriptive of these names. I call them "prior boxes" or "priors" in

keras_ssd300.pyto stay consistent with the original Caffe implementation, but everywhere else I use the name "anchor boxes" or "anchors". - "Labels": For the purpose of this project, datasets consist of "images" and "labels". Everything that belongs to the annotations of a given image is the "labels" of that image: Not just object category labels, but also bounding box coordinates. I also use the terms "labels" and "targets" more or less interchangeably throughout the documentation, although "targets" means labels specifically in the context of training.

- "Predictor layer": The "predictor layers" or "predictors" are all the last convolution layers of the network, i.e. all convolution layers that do not feed into any subsequent convolution layers.