React-mvc-lite: A simple, fine-grained MVC approach for React

Fine-grained MVC can provide unparalleled flexibility and dynamism since it relies on object oriented message dispatching to render components and it can also help with robustness (more modular code, less case logic). This tiny project implements MVC in React in an extremely simple way with very low overhead and very low boilerplate.

To use this package, you just define model classes with rendering methods. If you want or need a strict separation of presentation and domain, you can make separate view classes but you'll have provide a way to bridge from the models to the views. When it's practical, I advocate just putting the rendering methods in the models.

The MVC pattern was originally created in the 70s, for Smalltalk. The paper was published in 1988. There are several MVC approaches out there for doing MVC in React but my goal here is to provide lightweight, low boilerplate, fine-grained MVC for React.

Here's the general idea of MVC (courtesy of Wikimedia):

Web apps use this approach today but to many developers, the "view" is simply the entire web page. The controller processes the web request and consults models in the back-end to build the "view". This pattern works well but many apps could benefit from a finer-grained approach.

In Smalltalk, each widget has a model, view, and controller. This includes text fields, lists, buttons, menus, items in menus, and so on. The model for a text field holds a string and when the model changes, it automatically updates its view (the text field). Also, in Smalltalk, views contain views. What we think of today as "widgets", are views in Smalltalk, in the MVC sense.

So, instead of leaving web apps at a bulk approach, with only one view, the frontend can be comprised of many models, views, and controllers. This captures more of the original intent, flexibility, and power of the MVC paradigm (see the paper for details).

Normally, in a React app, you make components for data you want to render and each component references components for the data it uses directly, "inlining" them, so to speak.

You can see the example in action here, by the way.

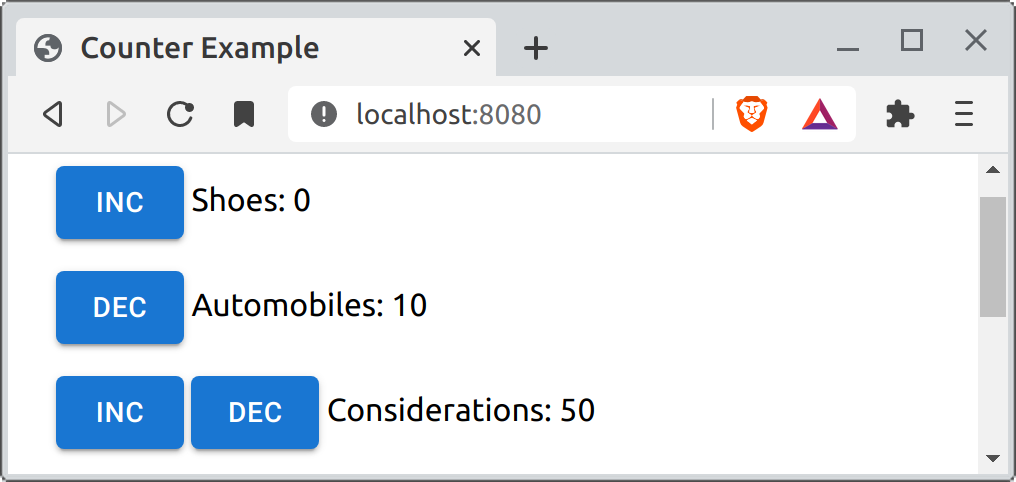

For this example, we'll use 3 types of counters: IncrementingCounter, DecrementingCounter, and IncDecCounter. The three counters really only differ in how they render (what buttons and how many of them) but in real life cases, the different objects would also vary in properties and behavior.

By the way, I do realize that my example is also a counter example.

For the inlining example, we end up with something like this:

function InlineCounters() {

return (

<>

{counterList.map((c, i)=> <InlineCounter counter={c} i={i}/>)}

</>

)

}

function InlineCounter({i, counter: c}: {i: number, counter: Counter}) {

const [value, setValue] = useState(c.value)

return (

<div className='mb-4' key={`inline-${i}`}>

{c.hasInc ?

<Button

variant='contained'

onClick={()=>{c.value++; setValue(c.value)}}>

Inc

</Button>

: <></>}

{c.hasInc && c.hasDec ? <> </> : <></>}

{c.hasDec ?

<Button

variant='contained'

onClick={()=>{c.value--; setValue(c.value)}}>

Dec

</Button>

: <></>}

{c.name}: {c.value}

</div>)

}There's nothing wrong with this approach and in many cases, this is

more practical and simpler than defining classes to represent

different configurations. The approach, however, is not very "OO"; it

uses case logic that you could avoid by using methods, maybe by

defining renderInc() and renderDec(). The fundamental structure

along with the state mangament, however, is in the InlineCounter

function. This means the counters aren't in charge of their own state

-- even if you provided renderInc() and renderDec(), they couldn't

call useState() except in very limited ways. If some counters, for

example, allow editing their name, they would need state for that but

others would not need it.

It takes a little discernment to decide whether it's fitting to make different classes for your model. When you need to, you can step out of "inline" mode and go into "MVC" mode. In MVC, different kinds of models have different kinds of views in different situations and there should be a straightforward way to choose the view for your model, like by just asking the model to render itself. A model could render itself differently depending on whether you're presenting an editor, a list element, or a select item for it.

Here's what Counters() looks like, an MVC version of

InlineCounters(). By calling c.renderEditor(), we let the model

decide how to render itself.

function Counters() {

return (

<>

{counterList.map((c, i)=> c.renderEditor(i))}

</>

)

}The renderEditor() method does have to use a tiny bit of ceremony

in order to interact properly with React because when you need to mange state, you have to

use a component; methods aren't React components.

renderEditor(index: number) {

return (<Render key={`inc-${index}`} render={()=> {

const controller = control(this, 'name', 'value')

console.log('render', this)

return (

<div className='mb-4'>

<Button

variant='contained'

onClick={controller(()=> this.value++)}>

Inc

</Button>

{this.name}: {this.value}

</div>

)

}}/>)

}The Render component provides a way to manage state from a method,

it simply delegates rendering to the function you give it. The

checkState function captures the state of the model -- it uses

deepEqual to detect state changes so you can give it properties that

contain structured data.

The controller is a function returned from the control() function,

which also captures the state of the model. In Smalltalk's MVC,

controllers process input events, so this is an analgous technique --

if your event handling is complex, you can gather it all into one

place instead of just using expressions like I do in the example.

So, that's it. Just use define your model and add rendering methods

that use <Render> and controller().

- build the dist directory with

npm run dist - run a webpack server with

npm run http