Deep Learning library in Labview. C++-based implementation of a feed-forward neural network.

Compilation requires version 3.3.5. of the Eigen library. Compiled with VisualStudio C++ 2015.

The library currently supports

1. Multi-feature Convolutional Layers 2. Multi-feature Deconvolutional Layers 3. Dense Layers 4. Dropout Layers 5. Max-Pooling Layers 6. Pass-On Layers (apply some elementwise function) 7. Mixture Density Layer (Probability distribution of likely output values) 9. Layer sharing between networks 10. Sidechannel layers (input additional data upstream into the network) 11. Vanilla & Wasserstein GAN-training functions

with three different non-linearities ReLu, Tanh and Sigmoid (can be different for each layer).

Gradient descent is performed in minibatches and several methods are available

1. Momentum-based descent (Nesterov's accelerated gradient currently commented out for technical reasons). 2. RMSprop 3. ADAM

Furthermore, the library offers two normalization modes that can be used irrespective of the gradient-stepping scheme.

1. weight normalisation 2. spectral normalization

All methods can be turned on and off dynamically during the training. All hyperparameters can always be changed during the training.

Currently I apply this to "inverse-holography". More about that below..

For my research, I need to be able to create complicated light patterns in my holographic optical tweezer setup (see e.g. Dynamic holographic optical tweezers, Curtis et al, 2002). My setup features a so-called spatial light modulator (SLM), essentially a liquid crystal screen with 800x600 pixels. Each pixel can advance or delay the phase of the incoming laser beam. In theory, this should allow me to shape the beam in any way I want. In practice, I need to know which value I should assign to each pixel of this SLM to create that particular beam shape.

That is not a simple problem. In fact, its non-trivial enough, that there are mountains of literature about it (there always are).

I thought that deep learning might be one way to solve this problem. We should be able to train a neural network on the forward problem (Hologram to Intensity). The inverse problem is an ongoing project described further below.

Mathematically speaking, the forward-transformation we wish to train our network on is a non-linear matrix-to-matrix problem. Our images are intensity only, so no additional colour channels. The transformation that the SLM imparts on the beam cannot be written down in any analytical form and even if this was possible, it would require precise knowledge of the geometry of the setup.

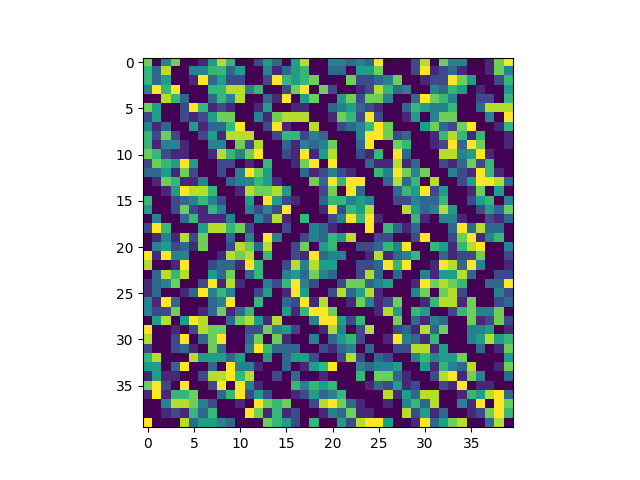

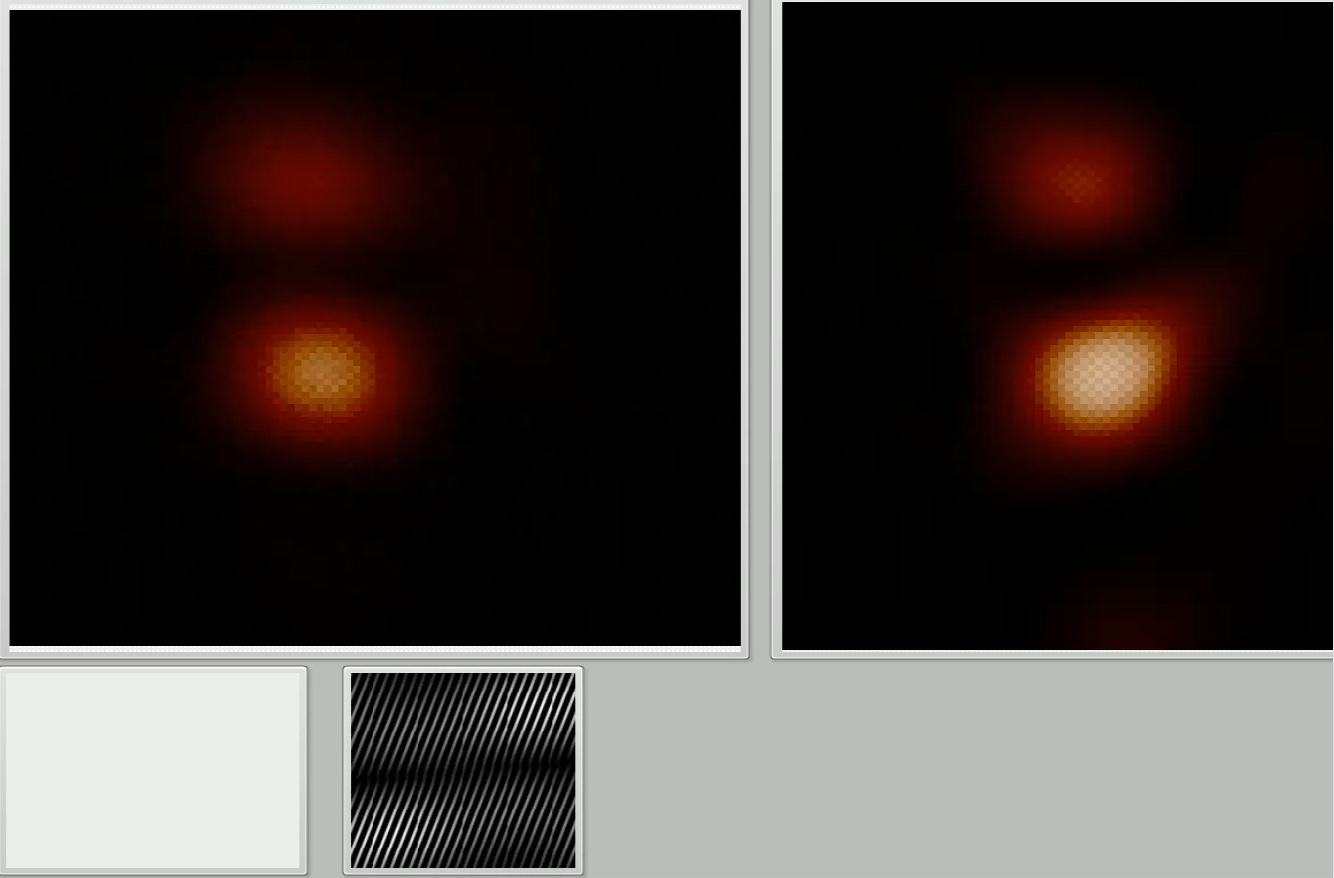

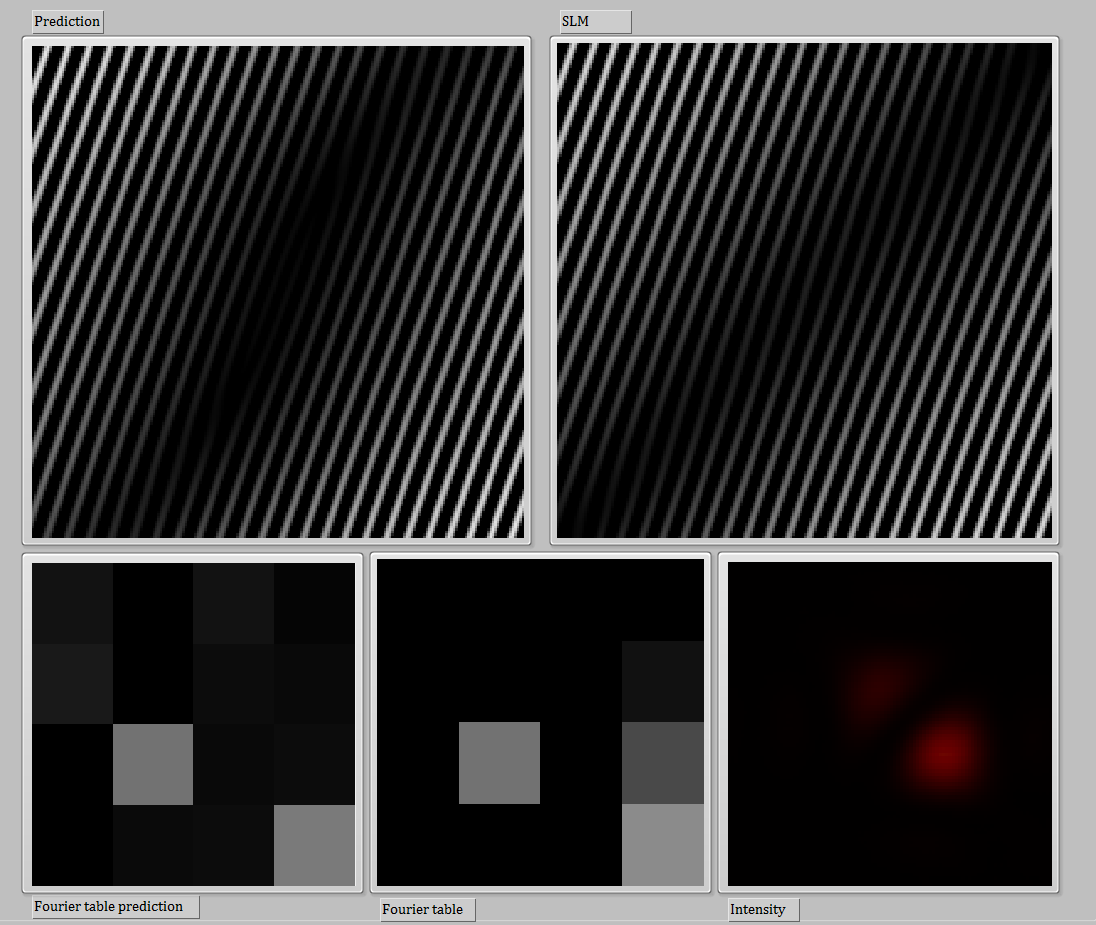

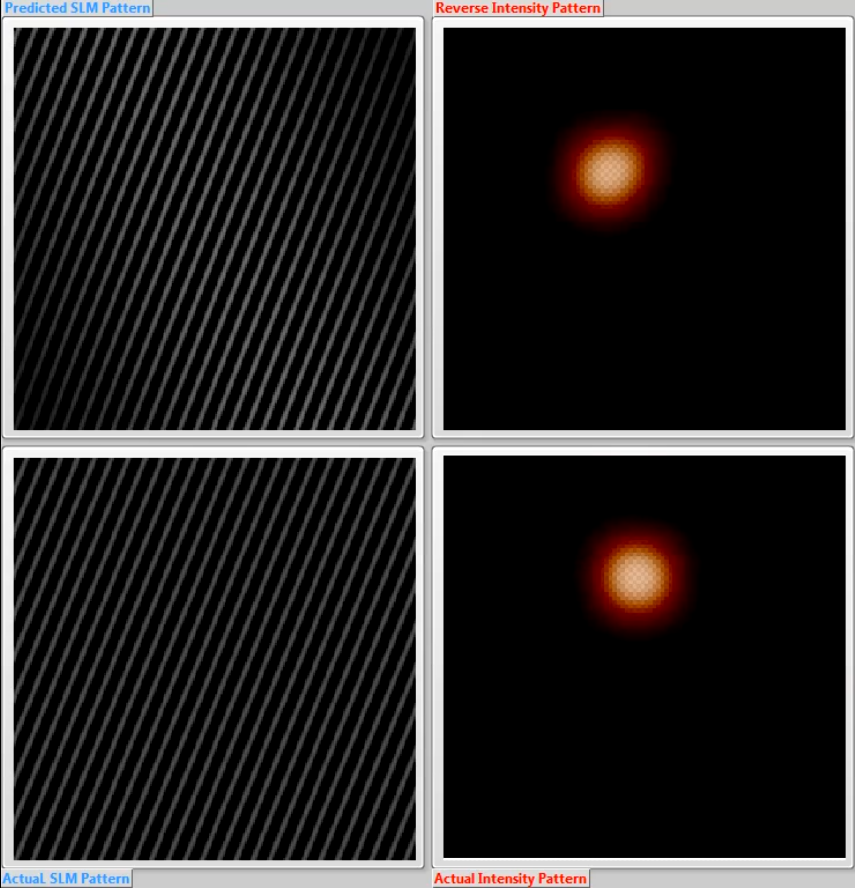

The following pictures should give you an impression of the transformation. You see pictures of the hologram with lots of striped patterns (left) and pictures of the corresponding laser light intensity fields (right), which can be pretty nice to look at.

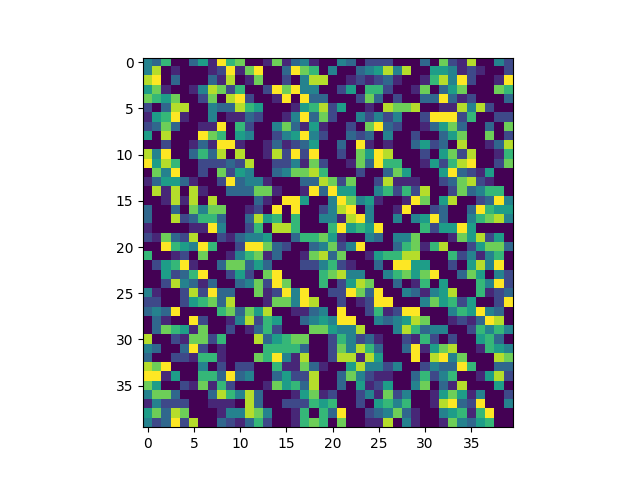

My results so far are encouraging. A convolutional network trained on the forward problem (Hologram -> Intensity), indeed predicts the laser light field correctly most of the time. Interestingly, the filters in the first convolutional layer actually converge to some sort of spatial frequency filter, as I had hoped.

When you follow the link below, you will see a video with a non-cherry picked selection of predictions (left) from the input hologram (bottom) and the actual intensity field, that I recorded (right).

The next challenge is to inversely "predict" the hologram from its own intensity field. This is an inverse problem and, unfortunately, it is "ill-posed", since there are many holograms that should give rise to the same or a very similar intensity field (optical aberrations that destroy this theoretical invariance might save us, but that is not yet clear).

I am currently trying to tackle this problem using Mixture-Density networks (see C Bishop 1994).

It it is probably hopeless to learn the holograms directly, since 800x600 (or any meaningful subset thereof) is too high dimensional. Instead, I chose a different approach. The network is trained in fourier space, which is much lower in dimensionality (8x8 if I only take the real part of the coefficients, otherwise it's 16x8). In any case, the fourier coefficients capture the essential information of the holograms (some sort of latent space?).

This trick should solve one my biggest headaches, which was the so-called 'phase problem': Two holograms that only differ in a global phase will produce the same intensity distribution. The mapping of holograms -> Intensity is not injective.

I thought, naively, that the mapping Fourier Coefficients -> Intensity might be injective. This, however, is not the case. I discovered that there are additional invariances in the problem arising from (1) non-linearities in the liquid crystals, which are difficult to completely get rid of and (2) light interference (laser light is coherent after all). So even in fourier space, the inverse problem is ill-posed.

UPDATE2: As Bishop writes in his book, Mixture Density models run into problems when the problem is invariant over not just a single branch of a function (like the inverse of x^2), but over a manifold of higher dimensionality (like r^2 = x^2 + y^2). This probably explains why mixture density approaches do not work for fourier dimensions higher than 4x4. The transformation could easily smear its invariance over some submanifold... so I changed tack a while ago.

A much better approach to learning the input distribution for inverse problems is to train a conditional generative adversarial network (see https://arxiv.org/pdf/1811.05910.pdf) on the problem. The idea is to condition both the critic and the generator on the output of the setup (the intensity) and ask the generator for a possible input that might have lead to this output.We had this idea here in Cambridge a couple of months ago ;) (seriously), but it got published in the mean time -> https://arxiv.org/pdf/1811.05910.pdf

for CT data (which is another famous inverse problem).

The inverse GAN approach works really well on all toy problems that I could conceive of, but it seems difficult to train the GAN's on my holography data. That's probably why the guys from Sweden used Wasserstein GAN's and trained them with gradient penalty.

Gradient penalty is almost impossible to implement without automatic differentiation though. I will therefore have to train the network using tensorflow and then export the graph into a format that allows me to transfer it to my network here, so that I can actually produce holograms.

Update -- Another idea might be to train the discriminator using spectral normalization, which I now added to the library. Spectral normalization achieved really good results on ImageNet, especially when it comes to variability of produced patterns, which is what I am looking for. It's also much easier to implement than Gradient penalty and not as computationally demanding.

The video below shows a conditional GAN trained on the inverse relation of the fourier table with the light field. I used only a single frequency to see if this works in principle (which it sort of does).

Arguably, the most naive approach to inverse problems might be to simply train two nets - one that simply learns the forward mapping, F: h -> I (where h is a hologramm and I is the intensity) and one that learns the inverse, B : I-> h' .

The loss function would have to read || F(B(I)) - I ||^2 and the training needs to proceed in two steps

1. Train forward mapping F: h->I, minimize( || F(h) - I || ^2 ) 2. Train backward mapping B inside forward F, i.e. minimize || F(B(I)) - I ||^2

One could even think about extending B with some latent variables Z, essentially turning it into a conditional generator. One could also try and add another training step, where F is trained on the output of Setup( B(I) )=I', since the holograms that B will produce won't likely be within the distribution of holograms that F sees during training....

Lots of things to try!