Jasmine Jerry Aloor and Alissa Chavalithumrong

- In a provided kitchen simulation enviroment pick and place food items into goal positions using a robotic arm (Franka "Panda")

- Place spam in drawer

- Place sugar on countertop

- Apply search, planning, constraint satisfaction, optimization, and probabilistic reasoning algorithms to real-world autonomy and decision-making problems

- Implement search, planning, constraint satisfaction, and optimization.

- Learn about problem formulations using .pddl

- Implement pybullet and pydrake libaries

- Every item location is known and can be reached by the robot.

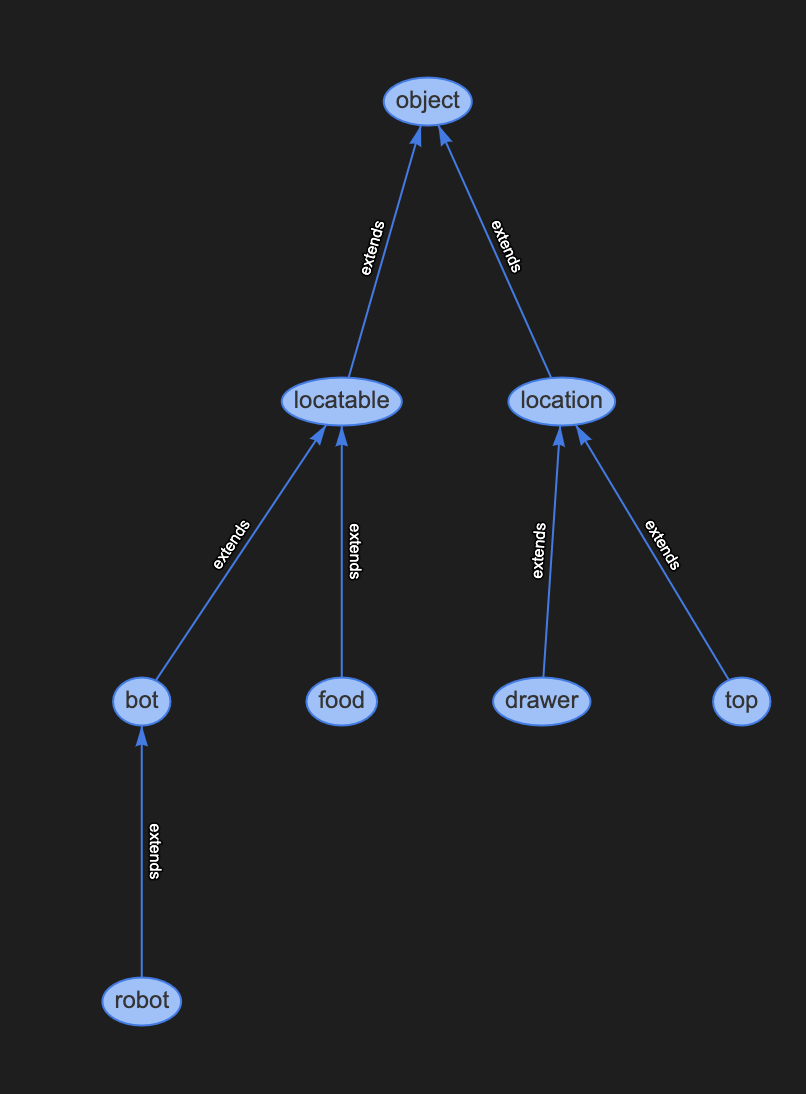

We design our object type to be made up of a location and a locatable. From there, we break down our locations to be top, and drawer. Similarly, our locatables are food and bot. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

In our problem.pddl file, through typing, we are able to specify our object. Spam and sugar are listed as a food type. The gripper is a special locatable that will be frequently queried, we use robot to further classify it. Our locations are broken down as drawer as drawer and countertop and stovetop as top. This is due to specific contraints that are required when placing items on a top vs drawer locations.

In our domain file, we have 4 predicates

(gripper-empty): is the gripper empty?(gripper-holding ?object - locatable): what object is the gripper holding?(on ?location - location ?object - locatable): what location is an object?(drawer-open): is the drawer open?

Figure 1: Domain heirarchy

domain.pddl: defines the “universal” aspects of the kitchen problemproblem.pddl: defines the global “worldly” aspects of the kitchen problemplanner.py: takes .pddl files and uses breath-first search to calculate a plan

planner.py output

Time: 0.00167083740234375s

plan:

move arm counter drawer

opendrawer arm drawer

move arm drawer stove

pickuptop arm sugar stove

move arm stove counter

droptop arm sugar counter

pickuptop arm spam counter

move arm counter drawer

dropdrawer arm spam drawer

closedrawer arm drawer

- In our first iteration of the .pddl files, we struggled with generating a valid domain and problem file that was solvable by our planner.

- All locatables (spam box and sugar box) and locations (countertop, drawer, stovetop) goal positions are known to the robot/motion planner. We also assume they are static and are at the sam e position during every run.

- Because the robotic gripper can reach all desired goal positions from one location near the kitchen, our base spawn location will be at that fixed position. Our spawn arm position will initalize in a neutral position where there are no possible collisions.

- The drawer is moved by bringing the arm close to the drawer handle and setting the open and shut ranges of the drawer appropriately. (We used 0.0 as closed and 0.4 as open)

- In the case of picking up, dropping, and opening/closing the drawer, we hard-coded each item to attach to the gripper when the gripper was brought close to it (with an error less than 0.05 in the joint space) and move with it.

The motion planner that was implimented was RRT (with goal biasing). We used RRT to calculate a path from our initial arm joint positions to a final joint goal position while avoiding collisions. We generated an activity plan from our PDDL planner, and from there parsed the actions and parameters.

For example, in the activity step move arm counter drawer, we would move the arm from it's current position at the counter to the drawer.

This is then passed into our Executor class in the root file project_run.py.

Determining the collision, distance, sample, and extend functions for the current simulation, which are subsequently given to the motion planner, was crucial to completing this task. The choice of whether to define points and paths in cartesian or joint space had to be made first. The latter was chosen since transferring this to cartesian space would be rather complicated and not unique, but in joint space all reachable configurations may simply be represented by the joint limits. Then, sampling in joint space can be easily accomplished by selecting a value at random between each joint's minimum and maximum joint angle. We used liner interpolator to determine the shortest path between two points. The cost funtion was the mean squared error from the current joint state to the target joint state

We then iterate through each step in of the activity plan and have the robot perform each action using RRT with goal biasing for the motions. We use a sample generator function similar to the example script provided. Once we get the manipulator arm to the required position from the path given by RRT, we proceed with the activity planner accordingly. As the objects are close by, we can generate the target joint angles using inverse kinematics (in-built functions which are provided by PyBullet).

Note: We had three types of visualiztion in our solution and decided to stick to the fastest one for the recording of the video in the interest of time. This made the arm motions awkward but we can sitch to more smoother arm motions for a more natural motion of the robot arm.

- We had the arm motions for RRT search tree which moved the arm violently for every sample joint ange set generated and had to remove that. We had to remove this feature as the application ended once a sample generated caused a collision.

- We had the arm iterate over the path found by RRT slowly showing a smoother motion (visualization in Section 3)

- We had a fast iteration over the path to quickly move the arm to the desired goal configurations (SHown in result video below)

collision.py: contains collision checking functions for rrtrrt2.py: contains the class for rrt functionsutils.py: helper functions for rrtplanner.py: planner implementationproject_run.py: final file to run the executor

This was the section that challenged us the most. Our unfamiliarity with pybullet, getting a Linux virtual machine compatible to run our arm-based Mac systems, and the libraries and installations involved took a while. The initial problem formulation made the inital startup for this section very time consuming.

A key challenge we faced was understanding how to implement a collision checker. We tried multiple methods including running a separate headless engine just to check if collision free paths exist for RRT. After a lot of brainstorming, we figured we could utilize the in-built pairwise link collision checking function. Once this was cleared, we could complete the implementation of our RRT algorithm.

The next challenge we faced was in integrating the activity plan and our RRT algorithm together. At times, RRT took a long time to find a solution to a target pose. After discussion and generating multiple ideas, we settled on using the planner to create a dictionary of required poses and joint angles for each of the activities mentioned. We then iterate over the plan again query the dictionary for the reuired target poses for the arm. This enabled us to get a fast solution.

A final challenge we faced was understanding how to stow the Spam container, and we settled to place it on the drawer and shut it accordingly.

In our optimization problem, we decided to minimize distance travelled per joint. By optimizing for distance, we are able to create the shortest and smoothest path. We seed our optimization problem with a path generated by RRT, and then use the general solver pydrake.Solve to calculate a solution.

Our constraint optimization problem is formalized above, where

Here is our resulting optimized trajectory. The red dots represent the trajectory generated by our RRT planner. The blue dots represents the new optimized trajectory.

Our trajectory optimization code is contained within optimization.py.

It consists of 3 main functions:

trajectory_file_to_nparray: converts trajectory_path.txt into a numpy arrayoptimization: runs the pydrake optimazation solver and produces the new optimized trajectory (optimized_trajectory_path.npy)run_optimization_simulation: runs simulation in pybullet

An issue that we ran into as formulating the optimization problem so that it was solvable by pydrake. IPopt and SNopt had issues solving matricies over 10 rows, which was difficult to use when our RRT code would produce trajectories of over 100 positions. We switched to using the general pydrake.Solve function, which allowed for pydrake to automatically select a solver that worked for our formulation.

Additionally, we had great difficulty in getting pyDrake installed in one of our systems due to multiple levels of library and dependency version mistmatch and had to rely on one system for this section. But we are glad it all worked out.

In this project we learnt a lot on manipulator motion planning and usage of PyBullet as a simulator. We were able to successfully come up with a solution for the three sections of the project.

Although our solution is not the most robust, due to several aspects of the arm movements that were 'hard coded' (such as goal arm positioning for objects and drawer movements), we were able to sucessfully compelete every section of the project.

Our group worked well together. We utilized our computing resources efficiently. We were able to creatively come up with solutions to problems and contribute equally on all sections. ❤️🔥