Those who study and work with humans are fundamentally interested in

questions of causation. More specifically, scientists, clinicians,

educators, and policymakers alike are often interested in causal

processes involving questions about when (timing) and at what levels

(dose) different factors influence human functioning and development, in

order to inform our scientific understanding and improve people’s lives.

However, for many, conceptual, methodological, and practical barriers

have prevented the use of methods for causal inference developed in

other fields.

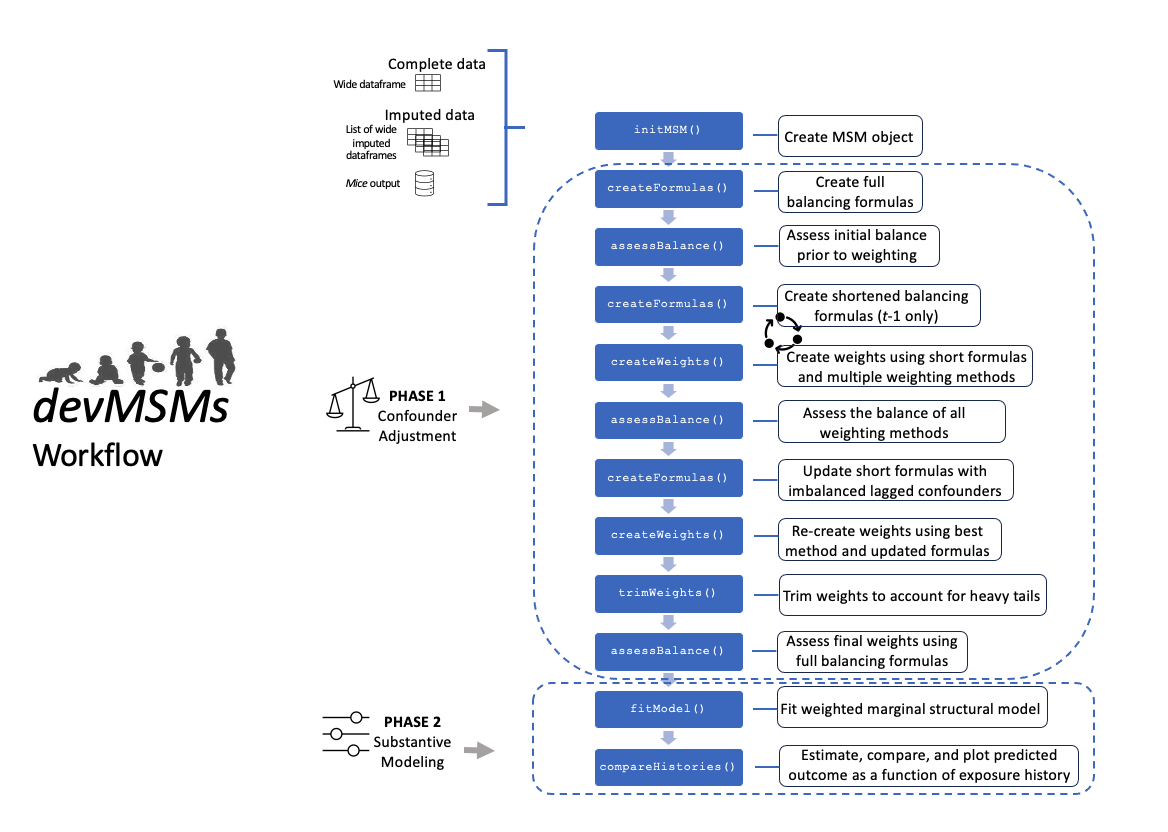

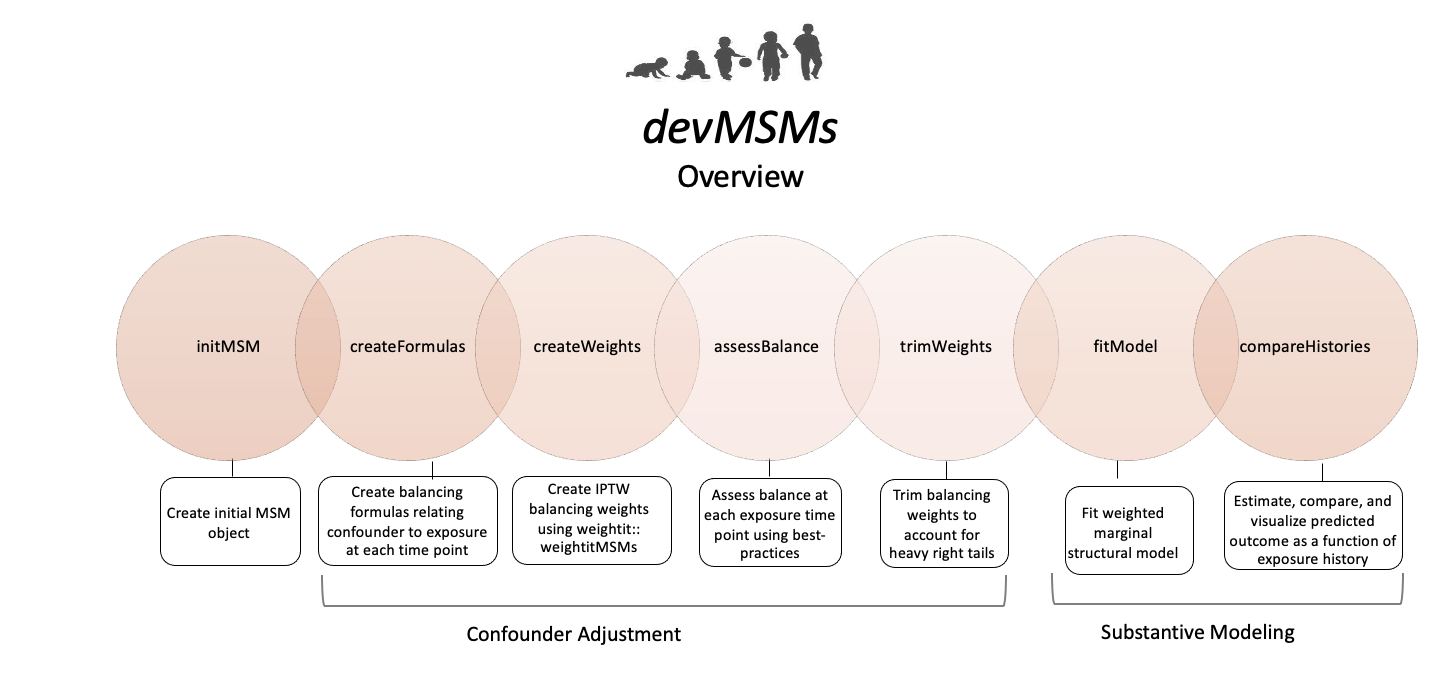

The goal of this devMSMs package and accompanying tutorial paper, Investigating Causal Questions in Human Development Using Marginal Structural Models: A Tutorial Introduction to the devMSMs Package in R (preprint), is to provide a set of tools for implementing marginal structural models (MSMs; Robins et al., 2000).

MSMs orginated in epidemiology and public health and represent one

under-utilized tool for improving causal inference with longitudinal

observational data, given certain assumptions. In brief, MSMs leverage

inverse-probability-of-treatment-weights (IPTW) and the potential

outcomes framework. MSMs first focus on the problem of confounding,

using IPTW to attenuate associations between measured confounders and an

exposure (e.g., experience, characteristic, event –from biology to the

broader environment) over time. A weighted model can then be fitted

relating a time-varying exposure and a future outcome. Finally, the

model-predicted effects of different exposure histories that vary in

dose and timing can be evaluated and compared as counterfactuals, to

reveal putative causal effects.

We employ the term exposure (sometimes referred to as “treatment” in

other literatures) to encompass a variety of environmental factors,

individual characteristics, or experiences that constitute the putative

causal events within a causal model. Exposures may be distal or

proximal, reflecting a developing child’s experience within different

environments at many levels (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994), ranging from

the family (e.g., parenting), home (e.g., economic strain), school

(e.g., teacher quality), neighborhood (e.g., diversity), to the greater

politico-cultural-economic context (e.g., inequality). Exposures could

also reflect factors internal to the child, including neurodevelopmental

(e.g., risk markers), physiological (e.g., stress), and behavioral

(e.g., anxiety) patterns to which the child’s development is exposed.

Core features of devMSMs include:

-

Flexible functions with built-in user guidance, drawing on established expertise and best practices for implementing longitudinal IPTW weighting and outcome modeling, to answer substantive causal questions about dose and timing

-

Functions that accept complete or imputed data to accommodate missingness often found in human studies

-

A novel recommended workflow, based on expertise from several disciplines, for using the devMSMs functions with longitudinal data (see Workflows vignettes)

-

An accompanying simulated longitudinal dataset, based on the real-world, Family Life Project (FLP) study of human development, for getting to know the package functions

-

An accompanying suite of helper functions to assist users in preparing and inspecting their data prior to the implementation of devMSMs

-

Executable, step-by-step user guidance for implementing the devMSMs workflow and preliminary steps in the form of vignettes geared toward users of all levels of R programming experience, along with a R markdown template file

-

A brief conceptual introduction, example empirical application, and additional resources in the accompanying tutorial paper

The package contains 7 core functions for implementing the two phases of

the MSM process: longitudinal confounder adjustment and outcome modeling

of longitudinal data with time-varying exposures.

Below is a summary of the terms used in the devMSMs vignettes and

functions. More details and examples can be found in the accompanying

manuscript.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exposure | Exposure or experience that constitutes the causal event of interest and is measured at at least two time points, with at least one time point occurring prior to the outcome. |

| Outcome | Any developmental construct measured at least once at a final outcome time point upon which the exposure is theorized to have causal effects. |

| Exposure Time Points | Time points in development when the exposure was measured, at which weights formulas will be created. |

| Exposure Epochs | (optional) Further delineation of exposure time points into meaningful units of developmental time, each of which could encompass multiple exposure time points, that together constitute exposure main effects in the outcome model and exposure histories. |

| Exposure Histories | Sequences of relatively high ('h') or low ('l') levels of exposure at each exposure time point or exposure epoch. |

| Exposure Dosage | Total cumulative exposure epochs/time points during which an individual experienced high (or low) levels of exposure, across an entire exposure history. |

| Confounder | Pre-exposure variable that represents a common cause of exposure at a given time point and outcome; adjusting for all of which successfully blocks all backdoor paths. |

| Time-varying confounder | A confounder that often changes over time (even if it is not measured at every time point), and is affected by prior exposure, either directly or indirectly. |

| Time invariant confounder | A confounder that occurs only at a single time point, prior to the exposure and remains stable and/or is not possibly affected by exposure. |

| Collider | A variable that represents a common effect of exposure at a given time point and outcome; adjusting for which introduces bias. |

devMSMs can be installed in R Studio from Github using the devtools package:

require(devtools, quietly = TRUE)

devtools::install_github("istallworthy/devMSMs")

library(devMSMs)The helper functions can be installed from the accompanying devMSMsHelpers repo:

devtools::install_github("istallworthy/devMSMsHelpers")

library(devMSMsHelpers)We propose a recommended workflow for using devMSMs to answer causal questions with longituinal data. We suggest using the vignettes in the order they appear in the Articles tab. After reading the accompanying manuscript, We recommend first reviewing the Terminology and Data Requirements vignettes as you begin preparing your data. We then recommend downloading the R markdown template file which contains all the code described in the Specify Core Inputs and Workflows vignettes (for binary (TBA) or continuous exposures) for implementing the steps below.

Please cite your use devMSMs using the following citation:

Stallworthy I, Greifer N, DeJoseph M, Padrutt E, Butts K, Berry D

(2024).

devMSMs: Implementing Marginal Structural Models with

Longitudinal Data. R package version 0.0.0.9000,

https://istallworthy.github.io/devMSMs/.

Please report any bugs at the following link: https://github.com/istallworthy/devMSMs/issues

Arel-Bundock, Diniz, M. A., Greifer, N., & Bacher, E. (2024). marginaleffects: Predictions, Comparisons, Slopes, Marginal Means, and Hypothesis Tests (0.12.0) [Computer software]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/marginaleffects/index.html.

Austin, P. C. (2011). An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(3), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Blackwell, M. (2013). A Framework for Dynamic Causal Inference in Political Science. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00626.x

Cole, S. R., & Hernán, M. A. (2008). Constructing Inverse Probability Weights for Marginal Structural Models. American Journal of Epidemiology, 168(6), 656–664. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn164

Eronen, M. I. (2020). Causal discovery and the problem of psychological interventions. New Ideas in Psychology, 59, 100785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2020.100785

Fong, C., Hazlett, C., & Imai, K. (2018).Covariate balancing propensity score for a continuous treatment: Application to the efficacy of political advertisements. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 12(1), 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1214/17-AOAS1101

Foster, E. M. (2010). Causal inference and developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 46(6), 1454–1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020204

Greifer N (2024).cobalt: Covariate Balance Tables and Plots. R package version 4.5.2, https://github.com/ngreifer/cobalt, https://ngreifer.github.io/cobalt/

Greifer N (2024). WeightIt: Weighting for Covariate Balance in Observational Studies. https://ngreifer.github.io/WeightIt/, https://github.com/ngreifer/WeightIt

Jackson, John W.(2016). Diagnostics for Confounding of Time-varying and Other Joint Exposures. Epidemiology, 2016 Nov, 27(6), 859-69. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000547.

Haber, N. A., Wood, M. E., Wieten, S., & Breskin, A.(2022). DAG With Omitted Objects Displayed (DAGWOOD): A framework for revealing causal assumptions in DAGs. Annals of Epidemiology, 68, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.01.001

Hernán, M., & Robins, J. (2024). Causal Inference: What If. CRC Press.

Hirano, K., & Imbens, G. W. (2004).The Propensity Score with Continuous Treatments. In Applied Bayesian Modeling and Causal Inference from Incomplete-Data Perspectives (pp. 73–84). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470090456.ch7

Kainz, K., Greifer, N., Givens, A., Swietek, K., Lombardi, B. M., Zietz, S., & Kohn, J. L. (2017). Improving Causal Inference: Recommendations for Covariate Selection and Balance in Propensity Score Methods. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8(2), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1086/691464

Loh, W. W., Ren, D., & West, S. G. (2024). Parametric g-formula for Testing Time-Varying Causal Effects: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How to Implement It in Lavaan. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 59(5), 995–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2024.2354228

Pishgar, F., Greifer, N., Leyrat, C., & Stuart, E. (2021). MatchThem: Matching andWeighting after Multiple Imputation. R Journal, 13(2), 292–305. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-073

Robins, J. M., Hernán, M.Á., & Brumback, B. (2000). Marginal Structural Models and Causal Inference in Epidemiology. Epidemiology, 11(5), 550–560.

Rubin, D. B. (2005). Causal Inference Using Potential Outcomes: Design, Modeling, Decisions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 100(469), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214504000001880

Rubin, D. B. (1974). Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66(5), 688–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037350

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

Stuart, E. A. (2008). Developing practical recommendations for the use of propensity scores: Discussion of ‘A critical appraisal of propensity score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003’ by Peter Austin, Statistics in Medicine. Statistics in Medicine, 27(12), 2062–2065. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3207

Textor, J. (2015). Drawing and Analyzing Causal DAGs with DAGitty.

Thoemmes, F., & Ong, A. D. (2016). A Primer on Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting and Marginal Structural Models. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815621645

Woodward, J. (2005). Making Things Happen: A Theory of Causal Explanation. Oxford University Press, USA.