gVisor is a user-space kernel, written in Go, that implements a substantial

portion of the Linux system surface. It includes an Open Container Initiative

(OCI) runtime called runsc that provides an isolation boundary between

the application and the host kernel. The runsc runtime integrates with Docker

and Kubernetes, making it simple to run sandboxed containers.

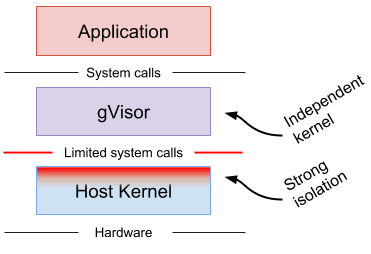

gVisor takes a distinct approach to container sandboxing and makes a different set of technical trade-offs compared to existing sandbox technologies, thus providing new tools and ideas for the container security landscape.

Containers are not a sandbox. While containers have revolutionized how we develop, package, and deploy applications, running untrusted or potentially malicious code without additional isolation is not a good idea. The efficiency and performance gains from using a single, shared kernel also mean that container escape is possible with a single vulnerability.

gVisor is a user-space kernel for containers. It limits the host kernel surface accessible to the application while still giving the application access to all the features it expects. Unlike most kernels, gVisor does not assume or require a fixed set of physical resources; instead, it leverages existing host kernel functionality and runs as a normal user-space process. In other words, gVisor implements Linux by way of Linux.

gVisor should not be confused with technologies and tools to harden containers against external threats, provide additional integrity checks, or limit the scope of access for a service. One should always be careful about what data is made available to a container.

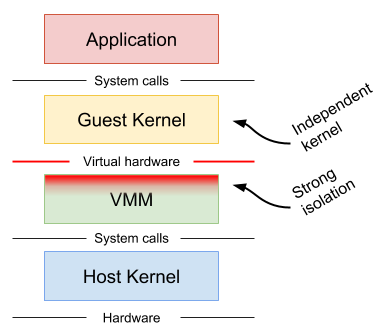

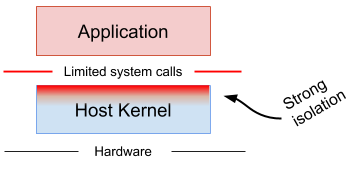

Two other approaches are commonly taken to provide stronger isolation than native containers.

Machine-level virtualization, such as KVM and Xen, exposes virtualized hardware to a guest kernel via a Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM). This virtualized hardware is generally enlightened (paravirtualized) and additional mechanisms can be used to improve the visibility between the guest and host (e.g. balloon drivers, paravirtualized spinlocks). Running containers in distinct virtual machines can provide great isolation, compatibility and performance (though nested virtualization may bring challenges in this area), but for containers it often requires additional proxies and agents, and may require a larger resource footprint and slower start-up times.

Rule-based execution, such as seccomp, SELinux and AppArmor, allows the specification of a fine-grained security policy for an application or container. These schemes typically rely on hooks implemented inside the host kernel to enforce the rules. If the surface can be made small enough (i.e. a sufficiently complete policy defined), then this is an excellent way to sandbox applications and maintain native performance. However, in practice it can be extremely difficult (if not impossible) to reliably define a policy for arbitrary, previously unknown applications, making this approach challenging to apply universally.

Rule-based execution is often combined with additional layers for defense-in-depth.

gVisor provides a third isolation mechanism, distinct from those mentioned above.

gVisor intercepts application system calls and acts as the guest kernel, without the need for translation through virtualized hardware. gVisor may be thought of as either a merged guest kernel and VMM, or as seccomp on steroids. This architecture allows it to provide a flexible resource footprint (i.e. one based on threads and memory mappings, not fixed guest physical resources) while also lowering the fixed costs of virtualization. However, this comes at the price of reduced application compatibility and higher per-system call overhead.

On top of this, gVisor employs rule-based execution to provide defense-in-depth (details below).

gVisor's approach is similar to User Mode Linux (UML), although UML virtualizes hardware internally and thus provides a fixed resource footprint.

Each of the above approaches may excel in distinct scenarios. For example, machine-level virtualization will face challenges achieving high density, while gVisor may provide poor performance for system call heavy workloads.

gVisor was written in Go in order to avoid security pitfalls that can plague kernels. With Go, there are strong types, built-in bounds checks, no uninitialized variables, no use-after-free, no stack overflow, and a built-in race detector. (The use of Go has its challenges too, and isn't free.)

gVisor intercepts all system calls made by the application, and does the necessary work to service them. Importantly, gVisor does not simply redirect application system calls through to the host kernel. Instead, gVisor implements most kernel primitives (signals, file systems, futexes, pipes, mm, etc.) and has complete system call handlers built on top of these primitives.

Since gVisor is itself a user-space application, it will make some host system calls to support its operation, but much like a VMM, it will not allow the application to directly control the system calls it makes.

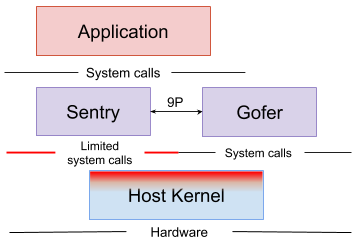

In order to provide defense-in-depth and limit the host system surface, the gVisor container runtime is normally split into two separate processes. First, the Sentry process includes the kernel and is responsible for executing user code and handling system calls. Second, file system operations that extend beyond the sandbox (not internal proc or tmp files, pipes, etc.) are sent to a proxy, called a Gofer, via a 9P connection.

The Gofer acts as a file system proxy by opening host files on behalf of the application, and passing them to the Sentry process, which has no host file access itself. Furthermore, the Sentry runs in an empty user namespace, and the system calls made by gVisor to the host are restricted using seccomp filters in order to provide defense-in-depth.

The Sentry implements its own network stack (also written in Go) called netstack. All aspects of the network stack are handled inside the Sentry — including TCP connection state, control messages, and packet assembly — keeping it isolated from the host network stack. Data link layer packets are written directly to the virtual device inside the network namespace setup by Docker or Kubernetes.

A network passthrough mode is also supported, but comes at the cost of reduced isolation (see below).

The Sentry requires a platform to implement basic context switching and memory mapping functionality. Today, gVisor supports two platforms:

-

The Ptrace platform uses SYSEMU functionality to execute user code without executing host system calls. This platform can run anywhere that

ptraceworks (even VMs without nested virtualization). -

The KVM platform (experimental) allows the Sentry to act as both guest OS and VMM, switching back and forth between the two worlds seamlessly. The KVM platform can run on bare-metal or on a VM with nested virtualization enabled. While there is no virtualized hardware layer -- the sandbox retains a process model -- gVisor leverages virtualization extensions available on modern processors in order to improve isolation and performance of address space switches.

There are several factors influencing performance. The platform choice has the largest direct impact that varies depending on the specific workload. There is no best platform: Ptrace works universally, including on VM instances, but applications may perform at a fraction of their original levels. Beyond the platform choice, passthrough modes may be useful for improving perfomance at the cost of some isolation.

These instructions will get you up-and-running sandboxed containers with gVisor and Docker.

Clone the gVisor repo:

git clone https://gvisor.googlesource.com/gvisor gvisor

cd gvisor

Build and install the runsc binary.

It is important to copy this binary to some place that is accessible to all

users, since runsc executes itself as user nobody to avoid unnecessary

privileges. The /usr/local/bin directory is a good choice.

bazel build runsc

sudo cp ./bazel-bin/runsc/linux_amd64_pure_stripped/runsc /usr/local/bin

Next, configure Docker to use runsc by adding a runtime entry to your Docker

configuration (/etc/docker/daemon.json). You may have to create this file if

it does not exist. Also, some Docker versions also require you to specify the

storage-driver field.

In the end, the file should look something like:

{

"runtimes": {

"runsc": {

"path": "/usr/local/bin/runsc"

}

}

}

You must restart the Docker daemon after making changes to this file, typically this is done via:

sudo systemctl restart docker

Now run your container in runsc:

docker run --runtime=runsc hello-world

Terminal support works too:

docker run --runtime=runsc -it ubuntu /bin/bash

gVisor can run sandboxed containers in a Kubernetes cluster with cri-o, although

this is not recommended for production environments yet. Follow these

instructions to run cri-o on a node in a Kubernetes

cluster. Build runsc and put it on the node, and set it as the

runtime_untrusted_workload in /etc/crio/crio.conf.

Any Pod without the io.kubernetes.cri-o.TrustedSandbox annotation (or with the

annotation set to false) will be run with runsc.

Currently, gVisor only supports Pods with a single container (not counting the ever-present pause container). Support for multiple containers within a single Pod is coming soon.

The gVisor test suite can be run with Bazel:

bazel test ...

To enable debug + system call logging, add the runtimeArgs below to your

Docker configuration (/etc/docker/daemon.json):

{

"runtimes": {

"runsc": {

"path": "/usr/local/bin/runsc"

"runtimeArgs": [

"--debug-log-dir=/tmp/runsc",

"--debug",

"--strace"

]

}

}

}

You may also want to pass --log-packets to troubleshoot network problems. Then

restart the Docker daemon:

sudo systemctl restart docker

Run your container again, and inspect the files under /tmp/runsc. The log file

with name boot will contain the strace logs from your application, which can

be useful for identifying missing or broken system calls in gVisor.

For high-performance networking applications, you may choose to disable the user space network stack and instead use the host network stack. Note that this mode decreases the isolation to the host.

Add the following runtimeArgs to your Docker configuration

(/etc/docker/daemon.json) and restart the Docker daemon:

{

"runtimes": {

"runsc": {

"path": "/usr/local/bin/runsc"

"runtimeArgs": [

"--network=host"

]

}

}

}

Depending on hardware and performance characteristics, you may choose to use a

different platform. The Ptrace platform is the default, but the KVM platform may

be specified by passing the --platform flag to runsc in your Docker

configuration (/etc/docker/daemon.json):

{

"runtimes": {

"runsc": {

"path": "/usr/local/bin/runsc"

"runtimeArgs": [

"--platform=kvm"

]

}

}

}

Then restart the Docker daemon.

The following applications/images have been tested:

- golang

- httpd

- java8

- jenkins

- mariadb

- memcached

- mongo

- mysql

- node

- php

- prometheus

- python

- redis

- registry

- tomcat

- wordpress

The following applications have been tested and may not yet work:

- elasticsearch: Requires unimplemented socket ioctls. See bug #2.

- nginx: Requires

ioctl(FIOASYNC), but see workaround in bug #1. - postgres: Requires SysV shared memory support. See bug #3.

gVisor implements a large portion of the Linux surface and while we strive to make it broadly compatible, there are (and always will be) unimplemented features and bugs. The only real way to know if it will work is to try. If you find a container that doesn’t work and there is no known issue, please file a bug indicating the full command you used to run the image. Providing the debug logs is also helpful.

If you’re having problems running a container with runsc it’s most likely due

to a compatibility issue or a missing feature in gVisor. See Debugging,

above.

For performance reasons, gVisor caches directory contents, and therefore it may not realize a new file was copied to a given directory. To invalidate the cache and force a refresh, create a file under the directory in question and list the contents again.

This bug is tracked in bug #4.

We plan to release a full paper with technical details and will include it here when available.

Join the gvisor-users mailing list to discuss all things gVisor.

Sensitive security-related questions and comments can be sent to the private gvisor-security mailing list.

See Contributing.md.