- zmq(全称:ZeroMQ)表面看起来像是一个嵌入式网络连接库,实际上是一个并发框架。

- zmq框架提供地套接字可以满足多种协议之间传输原子信息,如:线程间、进程间、TCP、广播等。

- zmq框架可以构建多对多地连接方式,如:扇出、发布-订阅、任务分发、请求-应答等。

- zmq框架的高速使其能胜任分布式应用场景

- zmq框架的异步IO机制让你能够构建多核应用程序,完成异步消息处理任务。

- zmq框架有着多语言支持,并能在几乎所有操作系统上运行。

- 概括地来说,这是一个高速并发消息通信框架,这是一个跨平台、跨系统、多语言的中间件软件。

- ZeroMQ官方相关文档:

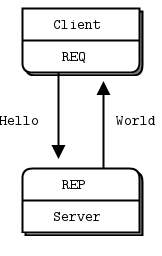

The REQ-REP socket pair is in lockstep. The client issues zmq_send() and then zmq_recv(), in a loop (or once if that’s all it needs). Doing any other sequence (e.g., sending two messages in a row) will result in a return code of -1 from the send or recv call. Similarly, the service issues zmq_recv() and then zmq_send() in that order, as often as it needs to.

ZeroMQ uses C as its reference language and this is the main language we’ll use for examples. If you’re reading this online, the link below the example takes you to translations into other programming languages.

//

// Hello World server in C++

// Binds REP socket to tcp://*:5555

// Expects "Hello" from client, replies with "World"

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

#ifndef _WIN32

#include <unistd.h>

#else

#include <windows.h>

#define sleep(n) Sleep(n)

#endif

int main () {

// Prepare our context and socket

zmq::context_t context (2);

zmq::socket_t socket (context, zmq::socket_type::rep);

socket.bind ("tcp://*:5555");

while (true) {

zmq::message_t request;

// Wait for next request from client

socket.recv (request, zmq::recv_flags::none);

std::cout << "Received Hello" << std::endl;

// Do some 'work'

sleep(1);

// Send reply back to client

zmq::message_t reply (5);

memcpy (reply.data (), "World", 5);

socket.send (reply, zmq::send_flags::none);

}

return 0;

}//

// Hello World client in C++

// Connects REQ socket to tcp://localhost:5555

// Sends "Hello" to server, expects "World" back

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

int main ()

{

// Prepare our context and socket

zmq::context_t context (1);

zmq::socket_t socket (context, zmq::socket_type::req);

std::cout << "Connecting to hello world server..." << std::endl;

socket.connect ("tcp://localhost:5555");

// Do 10 requests, waiting each time for a response

for (int request_nbr = 0; request_nbr != 10; request_nbr++) {

zmq::message_t request (5);

memcpy (request.data (), "Hello", 5);

std::cout << "Sending Hello " << request_nbr << "..." << std::endl;

socket.send (request, zmq::send_flags::none);

// Get the reply.

zmq::message_t reply;

socket.recv (reply, zmq::recv_flags::none);

std::cout << "Received World " << request_nbr << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}// Hello World server

#include <zmq.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <assert.h>

int main (void)

{

// Socket to talk to clients

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *responder = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_REP);

int rc = zmq_bind (responder, "tcp://*:5555");

assert (rc == 0);

while (1) {

char buffer [10];

zmq_recv (responder, buffer, 10, 0);

printf ("Received Hello\n");

sleep (1); // Do some 'work'

zmq_send (responder, "World", 5, 0);

}

return 0;

}// Hello World client

#include <zmq.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main (void)

{

printf ("Connecting to hello world server...\n");

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *requester = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_REQ);

zmq_connect (requester, "tcp://localhost:5555");

int request_nbr;

for (request_nbr = 0; request_nbr != 10; request_nbr++) {

char buffer [10];

printf ("Sending Hello %d...\n", request_nbr);

zmq_send (requester, "Hello", 5, 0);

zmq_recv (requester, buffer, 10, 0);

printf ("Received World %d\n", request_nbr);

}

zmq_close (requester);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}

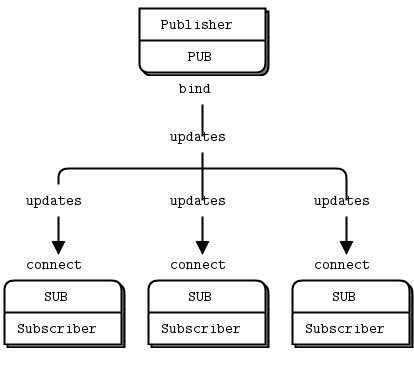

Note that when you use a SUB socket you must set a subscription using zmq_setsockopt() and SUBSCRIBE, as in this code. If you don’t set any subscription, you won’t get any messages. It’s a common mistake for beginners. The subscriber can set many subscriptions, which are added together. That is, if an update matches ANY subscription, the subscriber receives it. The subscriber can also cancel specific subscriptions. A subscription is often, but not always, a printable string. See zmq_setsockopt() for how this works.

The PUB-SUB socket pair is asynchronous. The client does zmq_recv(), in a loop (or once if that’s all it needs). Trying to send a message to a SUB socket will cause an error. Similarly, the service does zmq_send() as often as it needs to, but must not do zmq_recv() on a PUB socket.

In theory with ZeroMQ sockets, it does not matter which end connects and which end binds. However, in practice there are undocumented differences that I’ll come to later. For now, bind the PUB and connect the SUB, unless your network design makes that impossible.

There is one more important thing to know about PUB-SUB sockets: you do not know precisely when a subscriber starts to get messages. Even if you start a subscriber, wait a while, and then start the publisher, the subscriber will always miss the first messages that the publisher sends. This is because as the subscriber connects to the publisher (something that takes a small but non-zero time), the publisher may already be sending messages out.

This “slow joiner” symptom hits enough people often enough that we’re going to explain it in detail. Remember that ZeroMQ does asynchronous I/O, i.e., in the background. Say you have two nodes doing this, in this order:

- Subscriber connects to an endpoint and receives and counts messages.

- Publisher binds to an endpoint and immediately sends 1,000 messages.

Then the subscriber will most likely not receive anything. You’ll blink, check that you set a correct filter and try again, and the subscriber will still not receive anything.

Making a TCP connection involves to and from handshaking that takes several milliseconds depending on your network and the number of hops between peers. In that time, ZeroMQ can send many messages. For sake of argument assume it takes 5 msecs to establish a connection, and that same link can handle 1M messages per second. During the 5 msecs that the subscriber is connecting to the publisher, it takes the publisher only 1 msec to send out those 1K messages.

In Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns we’ll explain how to synchronize a publisher and subscribers so that you don’t start to publish data until the subscribers really are connected and ready. There is a simple and stupid way to delay the publisher, which is to sleep. Don’t do this in a real application, though, because it is extremely fragile as well as inelegant and slow. Use sleeps to prove to yourself what’s happening, and then wait for Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns to see how to do this right.

The alternative to synchronization is to simply assume that the published data stream is infinite and has no start and no end. One also assumes that the subscriber doesn’t care what transpired before it started up. This is how we built our weather client example.

So the client subscribes to its chosen zip code and collects 100 updates for that zip code. That means about ten million updates from the server, if zip codes are randomly distributed. You can start the client, and then the server, and the client will keep working. You can stop and restart the server as often as you like, and the client will keep working. When the client has collected its hundred updates, it calculates the average, prints it, and exits.

Some points about the publish-subscribe (pub-sub) pattern:

- A subscriber can connect to more than one publisher, using one connect call each time. Data will then arrive and be interleaved (“fair-queued”) so that no single publisher drowns out the others.

- If a publisher has no connected subscribers, then it will simply drop all messages.

- If you’re using TCP and a subscriber is slow, messages will queue up on the publisher. We’ll look at how to protect publishers against this using the “high-water mark” later.

- From ZeroMQ v3.x, filtering happens at the publisher side when using a connected protocol (tcp:@<>@ or ipc:@<>@). Using the epgm:@<//>@ protocol, filtering happens at the subscriber side. In ZeroMQ v2.x, all filtering happened at the subscriber side.

//

// Weather update server in C++

// Binds PUB socket to tcp://*:5556

// Publishes random weather updates

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#if (defined (WIN32))

#include <zhelpers.hpp>

#endif

#define within(num) (int) ((float) num * random () / (RAND_MAX + 1.0))

int main () {

// Prepare our context and publisher

zmq::context_t context (1);

zmq::socket_t publisher (context, zmq::socket_type::pub);

publisher.bind("tcp://*:5556");

publisher.bind("ipc://weather.ipc"); // Not usable on Windows.

// Initialize random number generator

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

while (1) {

int zipcode, temperature, relhumidity;

// Get values that will fool the boss

zipcode = within (100000);

temperature = within (215) - 80;

relhumidity = within (50) + 10;

// Send message to all subscribers

zmq::message_t message(20);

snprintf ((char *) message.data(), 20 ,

"%05d %d %d", zipcode, temperature, relhumidity);

publisher.send(message, zmq::send_flags::none);

}

return 0;

}//

// Weather update client in C++

// Connects SUB socket to tcp://localhost:5556

// Collects weather updates and finds avg temp in zipcode

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <iostream>

#include <sstream>

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

zmq::context_t context (1);

// Socket to talk to server

std::cout << "Collecting updates from weather server...\n" << std::endl;

zmq::socket_t subscriber (context, zmq::socket_type::sub);

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:5556");

// Subscribe to zipcode, default is NYC, 10001

const char *filter = (argc > 1)? argv [1]: "10001 ";

subscriber.setsockopt(ZMQ_SUBSCRIBE, filter, strlen (filter));

// Process 100 updates

int update_nbr;

long total_temp = 0;

for (update_nbr = 0; update_nbr < 100; update_nbr++) {

zmq::message_t update;

int zipcode, temperature, relhumidity;

subscriber.recv(update, zmq::recv_flags::none);

std::istringstream iss(static_cast<char*>(update.data()));

iss >> zipcode >> temperature >> relhumidity ;

total_temp += temperature;

}

std::cout << "Average temperature for zipcode '"<< filter

<<"' was "<<(int) (total_temp / update_nbr) <<"F"

<< std::endl;

return 0;

}// Weather update server

// Binds PUB socket to tcp://*:5556

// Publishes random weather updates

#include "zhelpers.h"

int main (void)

{

// Prepare our context and publisher

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *publisher = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PUB);

int rc = zmq_bind (publisher, "tcp://*:5556");

assert (rc == 0);

// Initialize random number generator

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

while (1) {

// Get values that will fool the boss

int zipcode, temperature, relhumidity;

zipcode = randof (100000);

temperature = randof (215) - 80;

relhumidity = randof (50) + 10;

// Send message to all subscribers

char update [20];

sprintf (update, "%05d %d %d", zipcode, temperature, relhumidity);

s_send (publisher, update);

}

zmq_close (publisher);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}// Weather update client

// Connects SUB socket to tcp://localhost:5556

// Collects weather updates and finds avg temp in zipcode

#include "zhelpers.h" // 此文件在官方示例代码仓库中

int main (int argc, char *argv [])

{

// Socket to talk to server

printf ("Collecting updates from weather server...\n");

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *subscriber = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_SUB);

int rc = zmq_connect (subscriber, "tcp://localhost:5556");

assert (rc == 0);

// Subscribe to zipcode, default is NYC, 10001

const char *filter = (argc > 1)? argv [1]: "10001 ";

rc = zmq_setsockopt (subscriber, ZMQ_SUBSCRIBE,

filter, strlen (filter));

assert (rc == 0);

// Process 100 updates

int update_nbr;

long total_temp = 0;

for (update_nbr = 0; update_nbr < 100; update_nbr++) {

char *string = s_recv (subscriber);

int zipcode, temperature, relhumidity;

sscanf (string, "%d %d %d",

&zipcode, &temperature, &relhumidity);

total_temp += temperature;

free (string);

}

printf ("Average temperature for zipcode '%s' was %dF\n",

filter, (int) (total_temp / update_nbr));

zmq_close (subscriber);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}

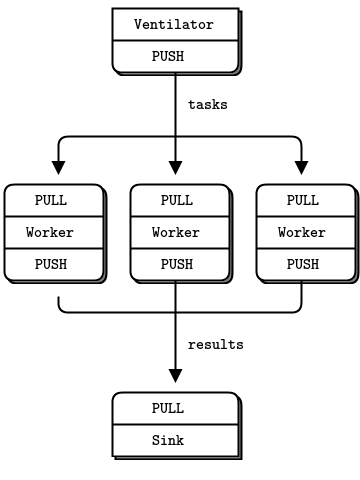

As a final example (you are surely getting tired of juicy code and want to delve back into philological discussions about comparative abstractive norms), let’s do a little supercomputing. Then coffee. Our supercomputing application is a fairly typical parallel processing model. We have:

- A ventilator that produces tasks that can be done in parallel

- A set of workers that process tasks

- A sink that collects results back from the worker processes

In reality, workers run on superfast boxes, perhaps using GPUs (graphic processing units) to do the hard math. Here is the ventilator. It generates 100 tasks, each a message telling the worker to sleep for some number of milliseconds:

//

// Task ventilator in C++

// Binds PUSH socket to tcp://localhost:5557

// Sends batch of tasks to workers via that socket

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <iostream>

#define within(num) (int) ((float) num * random () / (RAND_MAX + 1.0))

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

zmq::context_t context (1);

// Socket to send messages on

zmq::socket_t sender(context, ZMQ_PUSH);

sender.bind("tcp://*:5557");

std::cout << "Press Enter when the workers are ready: " << std::endl;

getchar ();

std::cout << "Sending tasks to workers...\n" << std::endl;

// The first message is "0" and signals start of batch

zmq::socket_t sink(context, ZMQ_PUSH);

sink.connect("tcp://localhost:5558");

zmq::message_t message(2);

memcpy(message.data(), "0", 1);

sink.send(message);

// Initialize random number generator

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

// Send 100 tasks

int task_nbr;

int total_msec = 0; // Total expected cost in msecs

for (task_nbr = 0; task_nbr < 100; task_nbr++) {

int workload;

// Random workload from 1 to 100msecs

workload = within (100) + 1;

total_msec += workload;

message.rebuild(10);

memset(message.data(), '\0', 10);

sprintf ((char *) message.data(), "%d", workload);

sender.send(message);

}

std::cout << "Total expected cost: " << total_msec << " msec" << std::endl;

sleep (1); // Give 0MQ time to deliver

return 0;

}// Task ventilator

// Binds PUSH socket to tcp://localhost:5557

// Sends batch of tasks to workers via that socket

#include "zhelpers.h"

int main (void)

{

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

// Socket to send messages on

void *sender = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PUSH);

zmq_bind (sender, "tcp://*:5557");

// Socket to send start of batch message on

void *sink = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PUSH);

zmq_connect (sink, "tcp://localhost:5558");

printf ("Press Enter when the workers are ready: ");

getchar ();

printf ("Sending tasks to workers...\n");

// The first message is "0" and signals start of batch

s_send (sink, "0");

// Initialize random number generator

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

// Send 100 tasks

int task_nbr;

int total_msec = 0; // Total expected cost in msecs

for (task_nbr = 0; task_nbr < 100; task_nbr++) {

int workload;

// Random workload from 1 to 100msecs

workload = randof (100) + 1;

total_msec += workload;

char string [10];

sprintf (string, "%d", workload);

s_send (sender, string);

}

printf ("Total expected cost: %d msec\n", total_msec);

zmq_close (sink);

zmq_close (sender);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}Here is the worker application. It receives a message, sleeps for that number of seconds, and then signals that it’s finished:

//

// Task worker in C++

// Connects PULL socket to tcp://localhost:5557

// Collects workloads from ventilator via that socket

// Connects PUSH socket to tcp://localhost:5558

// Sends results to sink via that socket

//

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

#include <string>

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

zmq::context_t context(1);

// Socket to receive messages on

zmq::socket_t receiver(context, ZMQ_PULL);

receiver.connect("tcp://localhost:5557");

// Socket to send messages to

zmq::socket_t sender(context, ZMQ_PUSH);

sender.connect("tcp://localhost:5558");

// Process tasks forever

while (1) {

zmq::message_t message;

int workload; // Workload in msecs

receiver.recv(&message);

std::string smessage(static_cast<char*>(message.data()), message.size());

std::istringstream iss(smessage);

iss >> workload;

// Do the work

s_sleep(workload);

// Send results to sink

message.rebuild();

sender.send(message);

// Simple progress indicator for the viewer

std::cout << "." << std::flush;

}

return 0;

}// Task worker

// Connects PULL socket to tcp://localhost:5557

// Collects workloads from ventilator via that socket

// Connects PUSH socket to tcp://localhost:5558

// Sends results to sink via that socket

#include "zhelpers.h"

int main (void)

{

// Socket to receive messages on

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *receiver = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PULL);

zmq_connect (receiver, "tcp://localhost:5557");

// Socket to send messages to

void *sender = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PUSH);

zmq_connect (sender, "tcp://localhost:5558");

// Process tasks forever

while (1) {

char *string = s_recv (receiver);

printf ("%s.", string); // Show progress

fflush (stdout);

s_sleep (atoi (string)); // Do the work

free (string);

s_send (sender, ""); // Send results to sink

}

zmq_close (receiver);

zmq_close (sender);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}Here is the sink application. It collects the 100 tasks, then calculates how long the overall processing took, so we can confirm that the workers really were running in parallel if there are more than one of them:

//

// Task sink in C++

// Binds PULL socket to tcp://localhost:5558

// Collects results from workers via that socket

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <time.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <iostream>

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

// Prepare our context and socket

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t receiver(context,ZMQ_PULL);

receiver.bind("tcp://*:5558");

// Wait for start of batch

zmq::message_t message;

receiver.recv(&message);

// Start our clock now

struct timeval tstart;

gettimeofday (&tstart, NULL);

// Process 100 confirmations

int task_nbr;

int total_msec = 0; // Total calculated cost in msecs

for (task_nbr = 0; task_nbr < 100; task_nbr++) {

receiver.recv(&message);

if (task_nbr % 10 == 0)

std::cout << ":" << std::flush;

else

std::cout << "." << std::flush;

}

// Calculate and report duration of batch

struct timeval tend, tdiff;

gettimeofday (&tend, NULL);

if (tend.tv_usec < tstart.tv_usec) {

tdiff.tv_sec = tend.tv_sec - tstart.tv_sec - 1;

tdiff.tv_usec = 1000000 + tend.tv_usec - tstart.tv_usec;

}

else {

tdiff.tv_sec = tend.tv_sec - tstart.tv_sec;

tdiff.tv_usec = tend.tv_usec - tstart.tv_usec;

}

total_msec = tdiff.tv_sec * 1000 + tdiff.tv_usec / 1000;

std::cout << "\nTotal elapsed time: " << total_msec << " msec\n" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

// Task sink

// Binds PULL socket to tcp://localhost:5558

// Collects results from workers via that socket

#include "zhelpers.h"

int main (void)

{

// Prepare our context and socket

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *receiver = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_PULL);

zmq_bind (receiver, "tcp://*:5558");

// Wait for start of batch

char *string = s_recv (receiver);

free (string);

// Start our clock now

int64_t start_time = s_clock ();

// Process 100 confirmations

int task_nbr;

for (task_nbr = 0; task_nbr < 100; task_nbr++) {

char *string = s_recv (receiver);

free (string);

if (task_nbr % 10 == 0)

printf (":");

else

printf (".");

fflush (stdout);

}

// Calculate and report duration of batch

printf ("Total elapsed time: %d msec\n",

(int) (s_clock () - start_time));

zmq_close (receiver);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}

The average cost of a batch is 5 seconds. When we start 1, 2, or 4 workers we get results like this from the sink:

- 1 worker: total elapsed time: 5034 msecs.

- 2 workers: total elapsed time: 2421 msecs.

- 4 workers: total elapsed time: 1018 msecs.

Let’s look at some aspects of this code in more detail:

- The workers connect upstream to the ventilator, and downstream to the sink. This means you can add workers arbitrarily. If the workers bound to their endpoints, you would need (a) more endpoints and (b) to modify the ventilator and/or the sink each time you added a worker. We say that the ventilator and sink are stable parts of our architecture and the workers are dynamic parts of it.

- We have to synchronize the start of the batch with all workers being up and running. This is a fairly common gotcha in ZeroMQ and there is no easy solution. The zmq_connect method takes a certain time. So when a set of workers connect to the ventilator, the first one to successfully connect will get a whole load of messages in that short time while the others are also connecting. If you don’t synchronize the start of the batch somehow, the system won’t run in parallel at all. Try removing the wait in the ventilator, and see what happens.

- The ventilator’s PUSH socket distributes tasks to workers (assuming they are all connected before the batch starts going out) evenly. This is called load balancing and it’s something we’ll look at again in more detail.

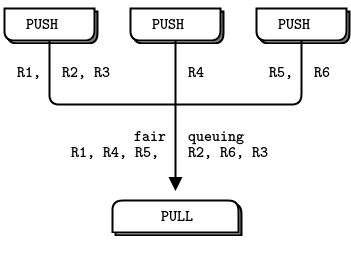

- The sink’s PULL socket collects results from workers evenly. This is called fair-queuing.

The pipeline pattern also exhibits the “slow joiner” syndrome, leading to accusations that PUSH sockets don’t load balance properly. If you are using PUSH and PULL, and one of your workers gets way more messages than the others, it’s because that PULL socket has joined faster than the others, and grabs a lot of messages before the others manage to connect. If you want proper load balancing, you probably want to look at the load balancing pattern in Chapter 3 - Advanced Request-Reply Patterns.