This misleadingly titled ‘game’ was my final project at SPICED Academy. Made using Unity Editor, it is a 3D online multiplayer game featuring third-person controls, running in the browser, served by an Ubuntu instance hosted on Amazon EC2.

I used the final project assignment as an opportunity to teach myself a new coding paradigm. Unity had come recommended to me by a friend and mentor in the programming industry as an excellent, professional-quality tool for designing games. Though Unity Editor is a sophisticated SDK with an excellent GUI, programming concepts remain integral to its use.

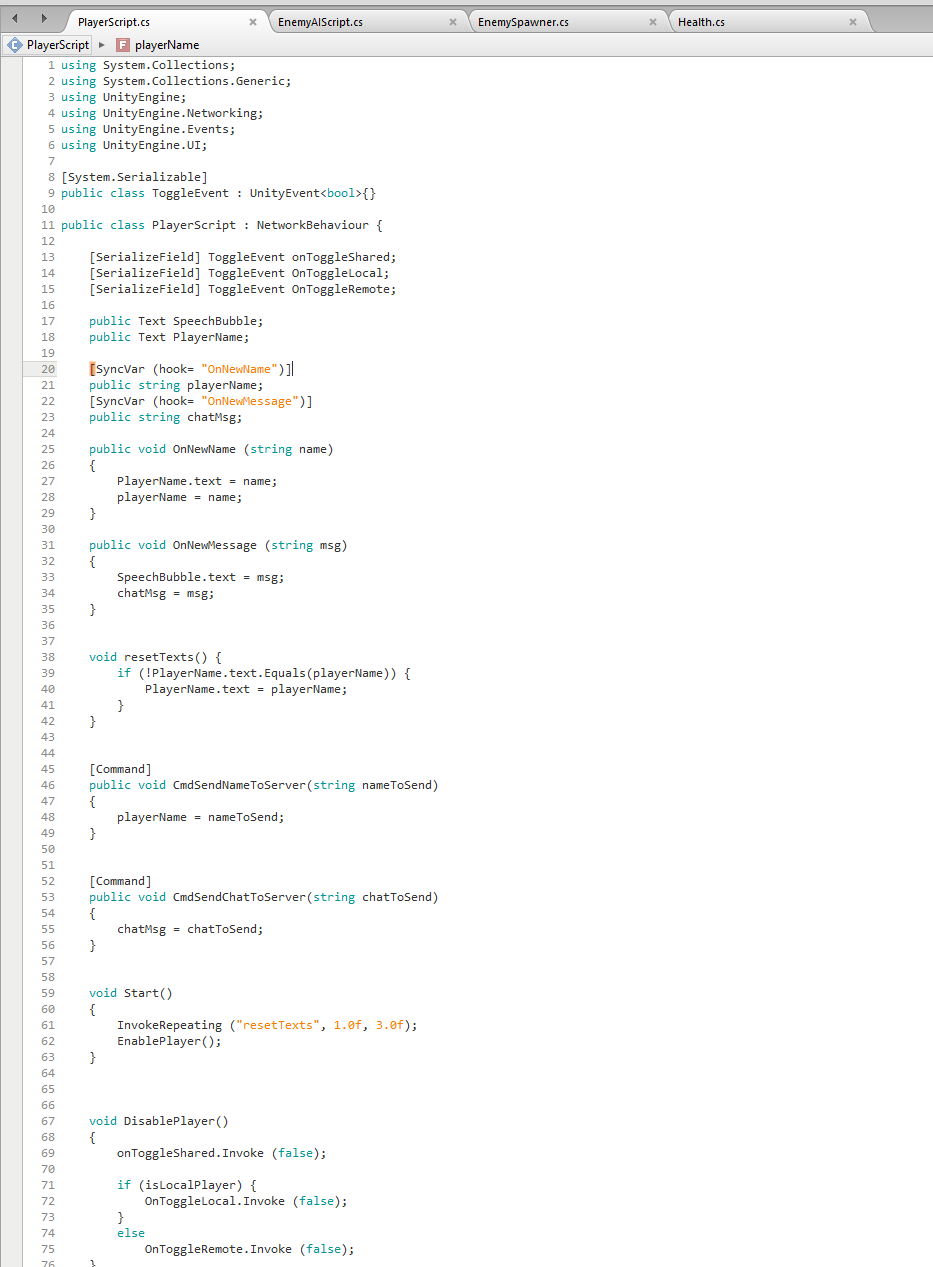

Not least among them is the scripting language. All scripting is done in C#, which was a new experience for me. Strictly-typed, there was a bit of a learning curve in adjusting to this new language while simultaneously learning how to relate separate scripts to “Game Objects,” and each other, within the game engine. Like in JavaScript, a kind of representational I/O logic governs almost everything you do in Unity, where Game Objects function much like normal objects in OOP. These objects become very complex as further “components” are attached to them. Components also work much like objects in OOP, and it is amongst these components that C# scripting is also attached and thus introduced to the game scene.

Scripts (mine for this game are here) sometimes act upon the respective Game Object itself, or sometimes on a specific component, or sometimes on an entirely different Game Object (or even a component on a different Game Object). Frequently, it is some combination of all these behaviors. The Network Manager is a kind of component, and though Unity does much of the hard work in networking for you (should you use this component), it nonetheless adds more complexity to the set of objective relations which define your game.

As my prior work with socket.io showed, I have a real interest in real-time connectivity over the internet. After I familiarized myself with the Editor (by way of the excellent documentation and tutorials provided by Unity), I became determined to host a multiplayer game on Heroku or elsewhere, via whatever means necessary. At some point it became apparent that, due to the realities of networking (specifically that Websockets in Unity would need their own port for communication), I would need to set up a separate, dedicated server in addition to the client representation on Heroku. Thus I dove into Amazon EC2, a very dense topic in and of itself, successfully setting up an Ubuntu instance which now hosts my headless Linux server, most likely live as you are reading this. Go ahead: try out Zombie Smash on Heroku!

The gameplay is minimal at present, but there are already some exciting elements there: players can simultaneously login, set a gamer tag and, using a 2d billboard attached to their character within the game world, engage in rudimentary chat. A few animation-less demons are sometimes encountered; if they can reduce the player’s health to zero (by catching up to the player), it sparks an instant respawn. Much work needs to be done to improve the execution of the actual gameplay. But hey, I taught myself Unity, C#, and AWS EC2 in the span of week. That’s pretty cool.

Note: if the Heroku App loads but does not successfully connect to the server, please reach out to me directly! Either via email (mullin.mm@gmail.com) or a PM on LinkedIn.

- Unity

- C#

- AWS EC2

- Linux/Ubuntu

- Heroku

- Unity Asset Store for the free assets (individual thanks will be posted soon)

- freesound.org for the SFX (same)

- Matthew Kennon for the music you hear