This repository contains an implementation of Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) learning using PyTorch. Double DQN builds on the original DQN by addressing the issue of overestimation in action-value estimation. In standard DQN, the max operator used in the target update tends to overestimate the Q-values, which can lead to suboptimal policies. Double DQN mitigates this by decoupling the action selection and evaluation steps: the online network selects the action, while the target network evaluates the value of that action. This adjustment leads to more accurate value estimates and, consequently, better performance.

The code is tested against various Atari environments provided by the Gymnasium library. These environments are vectorized for efficient parallel processing. A custom wrapper is implemented to preprocess the frames following the methodology outlined in the original DQN paper (including the use of reward clipping). For optimal performance, it is recommended to use the 'NoFrameskip' versions of the environments.

It's recommended to use a Conda environment to manage dependencies and avoid conflicts. You can create and activate a new Conda environment with the following commands:

conda create -n ddqn_env python=3.11

conda activate ddqn_envAfter activating the environment, install the required dependencies using:

pip install -r requirements.txtYou can run the algorithm on any supported Gymnasium environment with a discrete action space using the following command:

python main.py --env 'MsPacmanNoFrameskip-v4'-

Environment Selection: Use

-eor--envto specify the Gymnasium environment. The default isNone, so you must specify an environment.Example:

python main.py --env 'PongNoFrameskip-v4' -

Number of Learning Steps: Use

--n_stepsto define how many training steps the agent should undergo. The default is 100,000 steps.Example:

python main.py --env 'BreakoutNoFrameskip-v4' --n_steps 200000 -

Parallel Environments: Use

--n_envsto specify the number of parallel environments to run during training. The default is 32 environments, optimizing the training process.Example:

python main.py --env 'AsterixNoFrameskip-v4' --n_envs 16 -

Continue Training: Use

--continue_trainingto determine whether to continue training from saved weights. The default isTrue, allowing you to resume training from where you left off.Example:

python main.py --env 'AsteroidsNoFrameskip-v4' --continue_training False

Using a Conda environment along with these flexible command-line options will help you efficiently manage your dependencies and customize the training process for your specific needs.

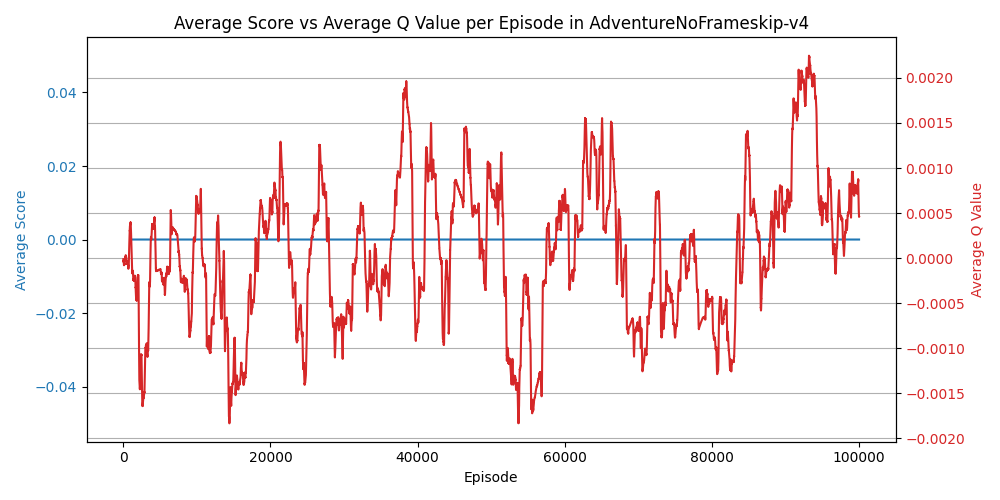

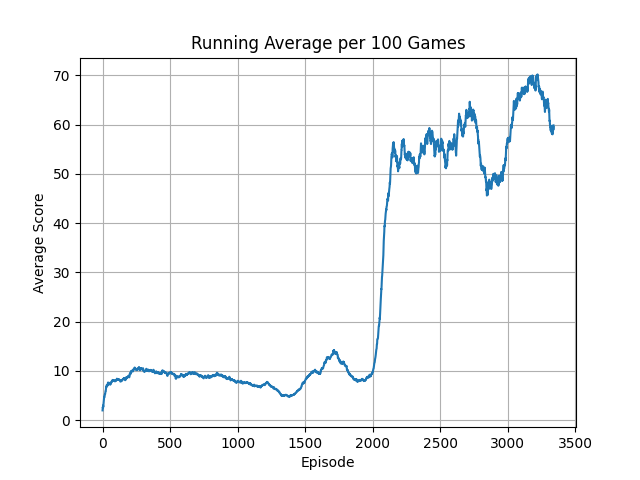

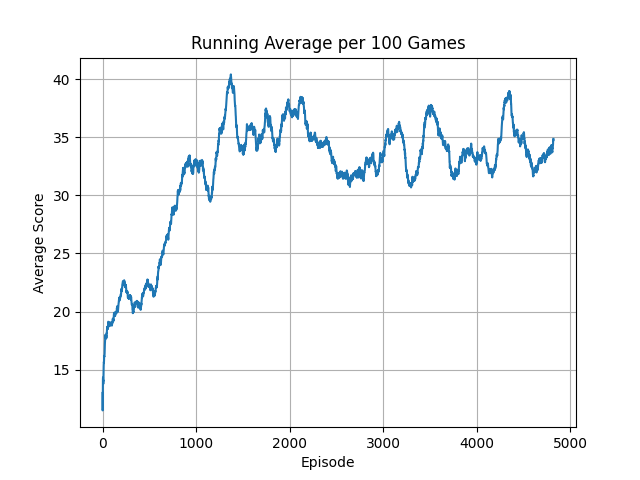

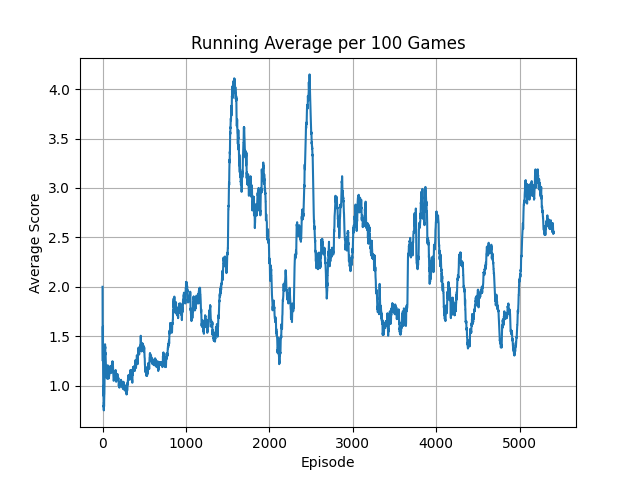

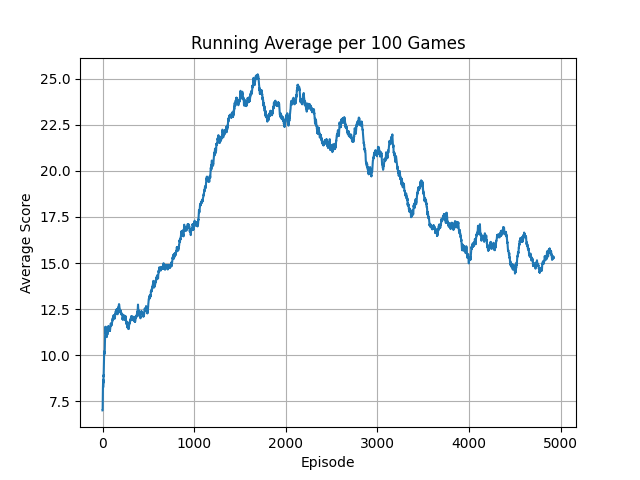

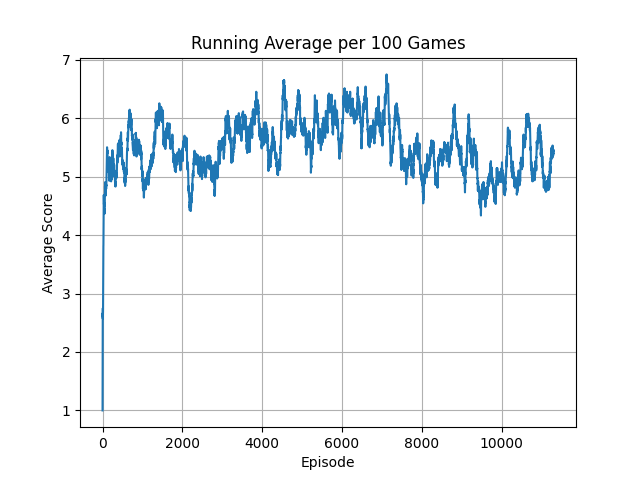

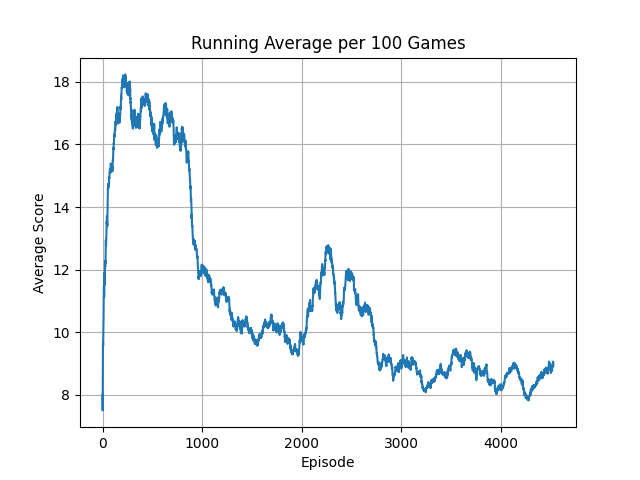

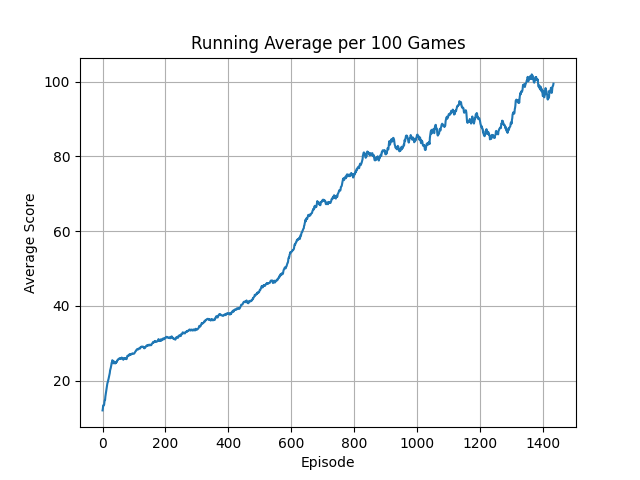

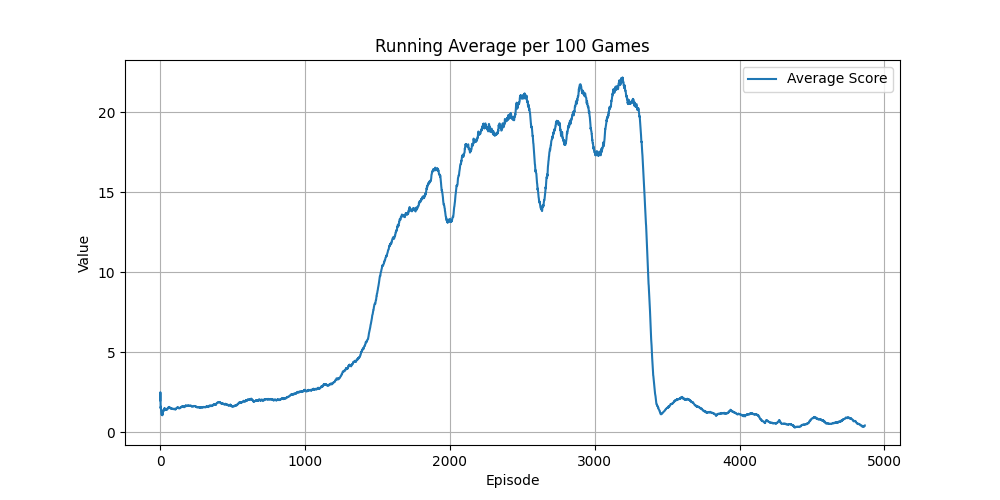

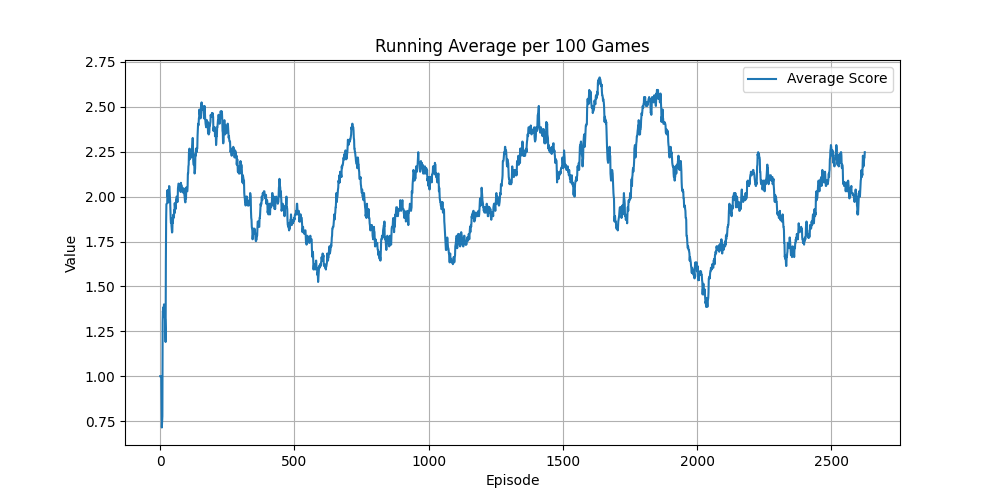

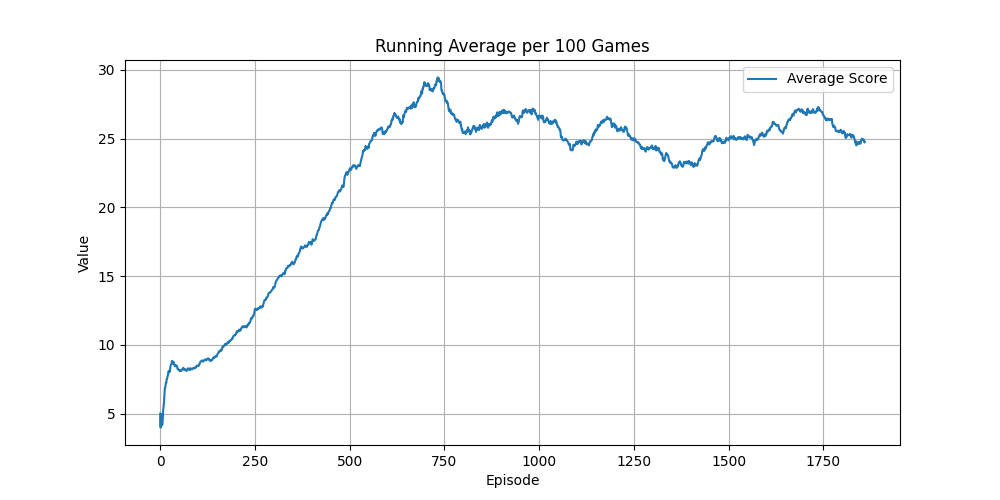

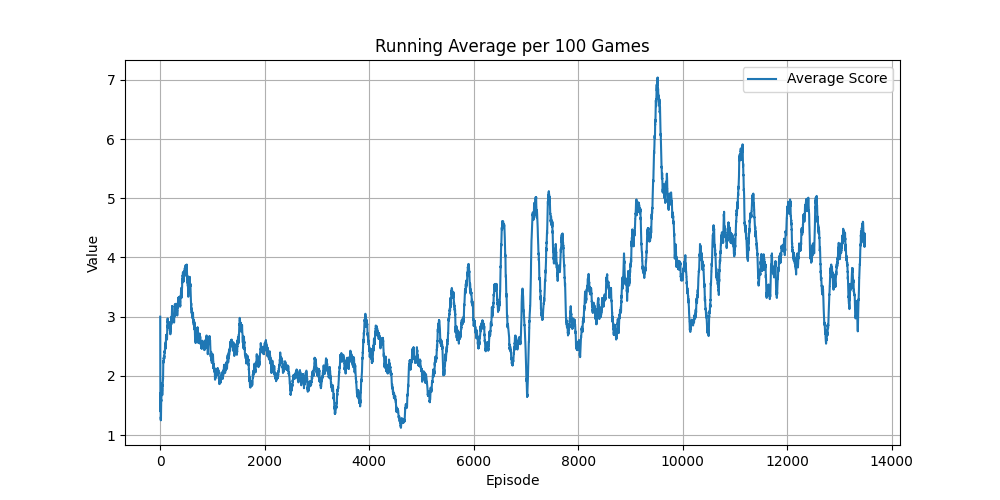

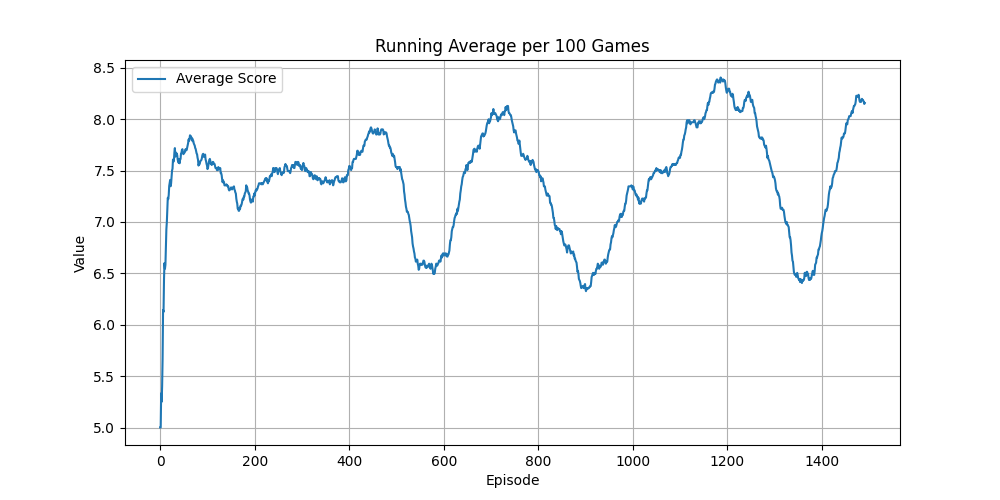

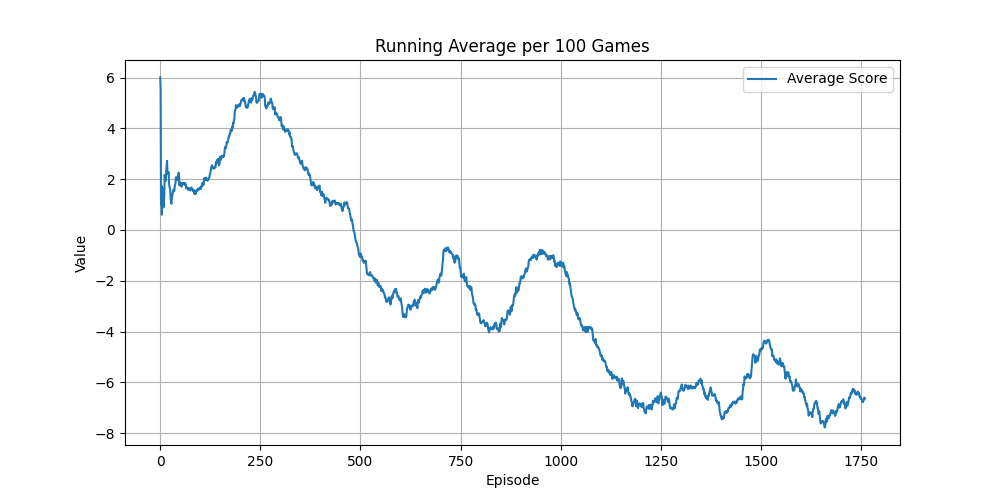

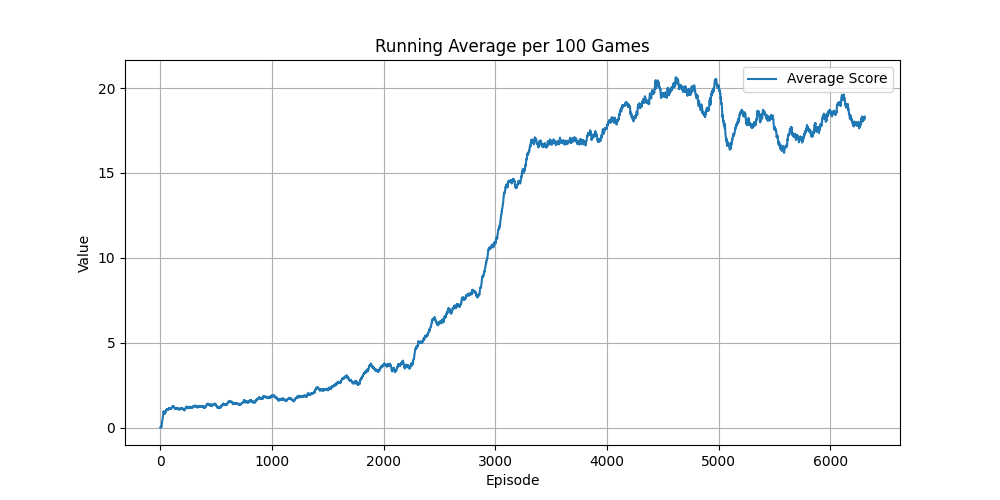

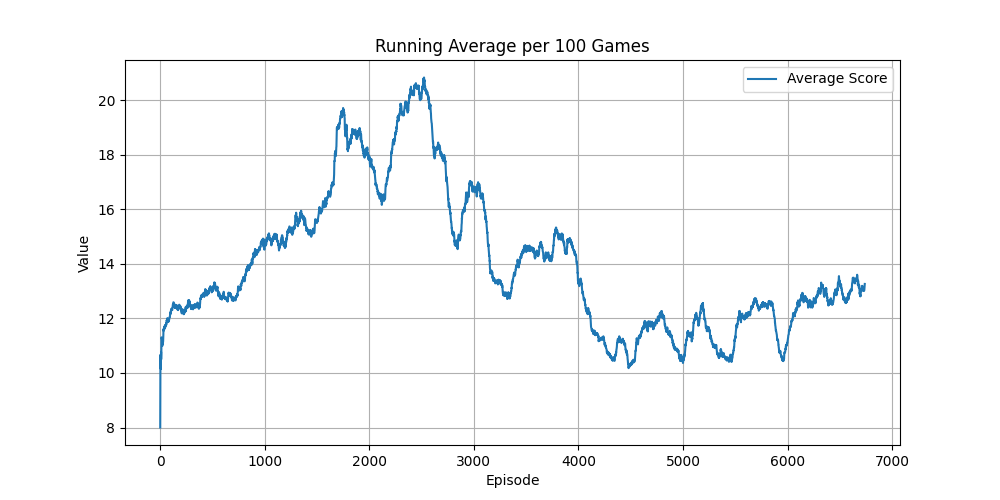

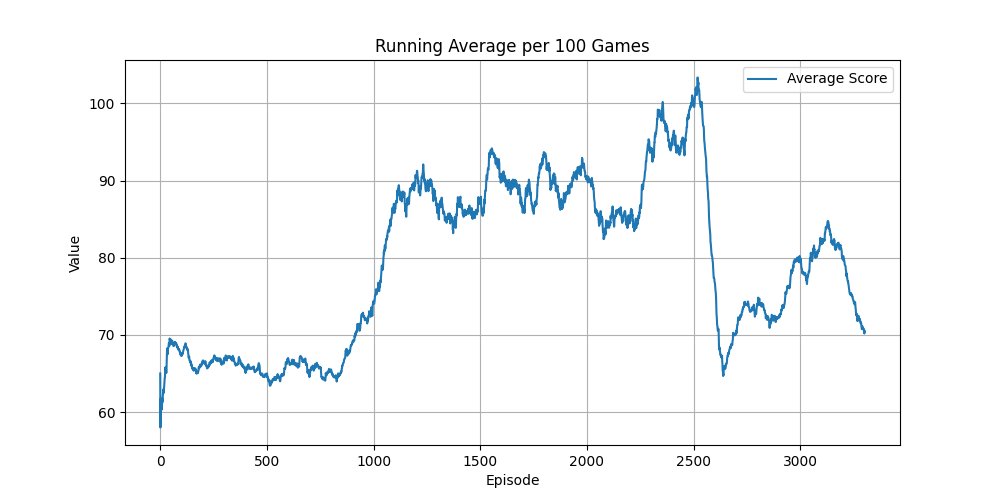

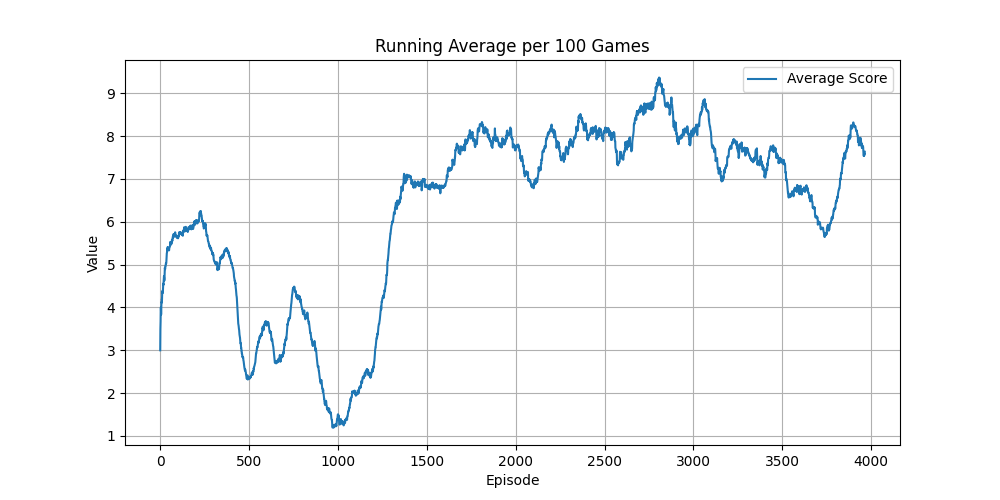

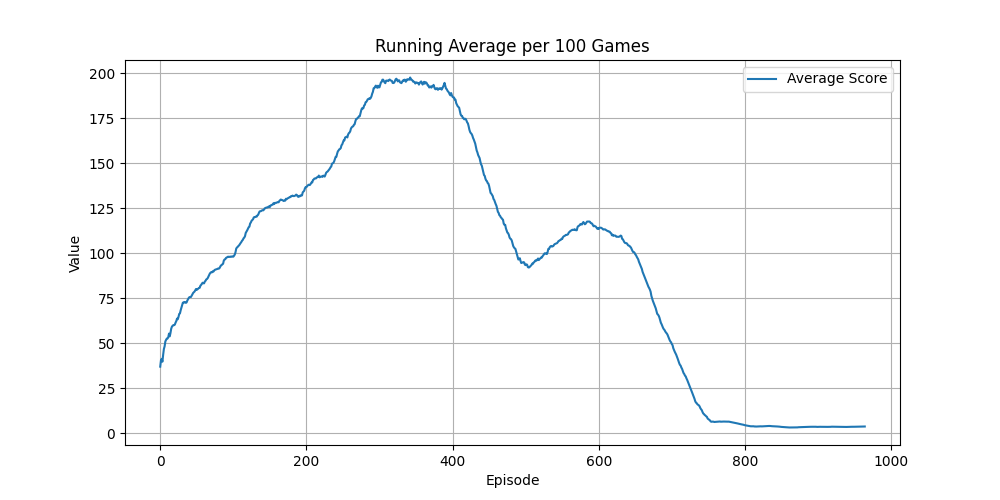

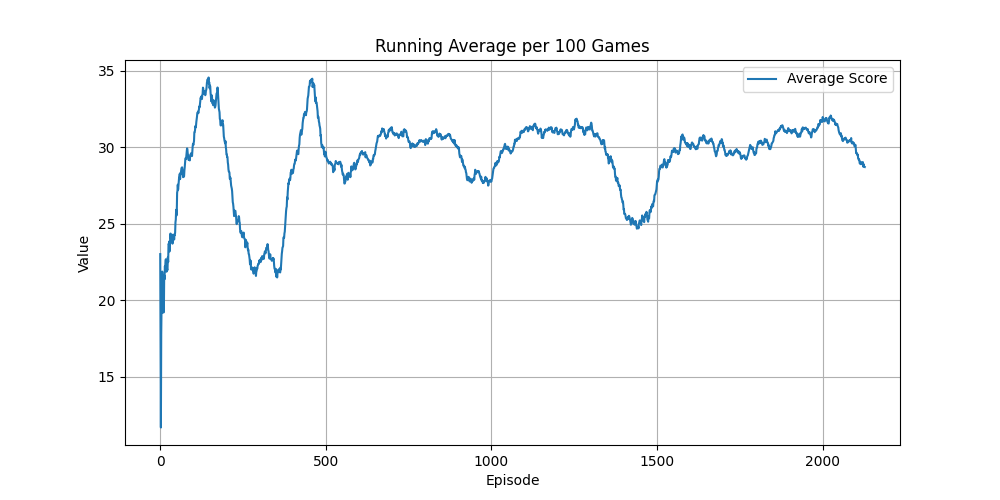

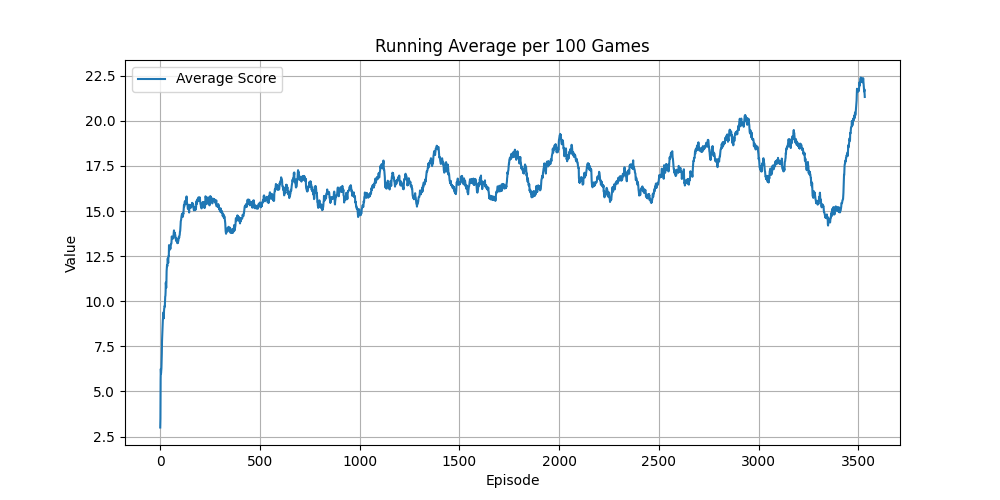

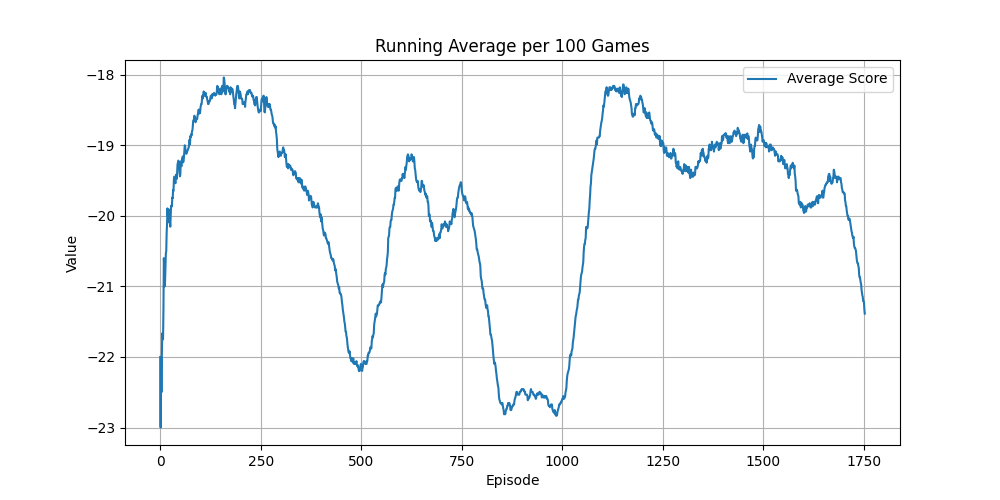

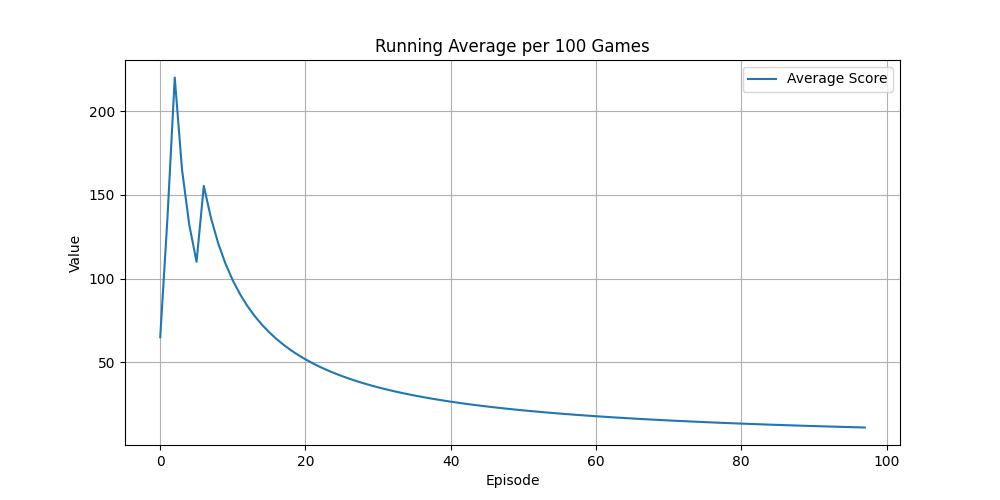

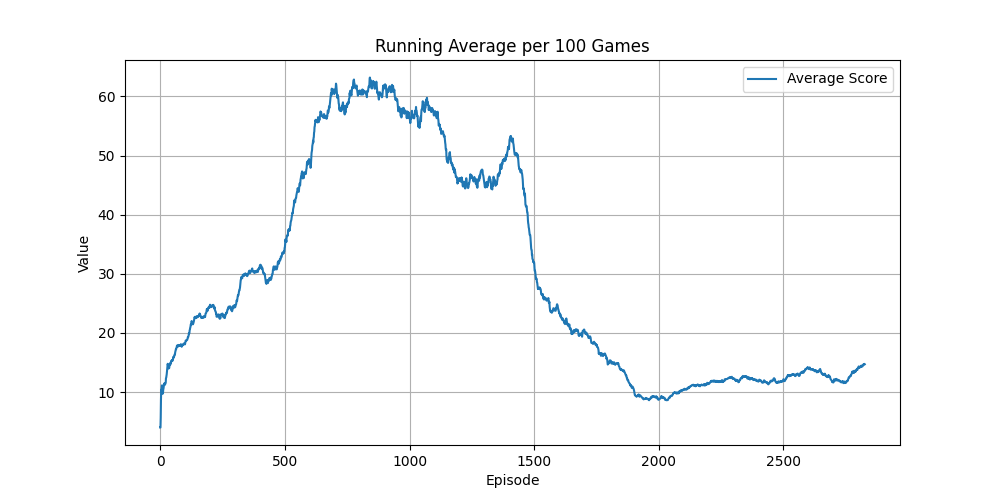

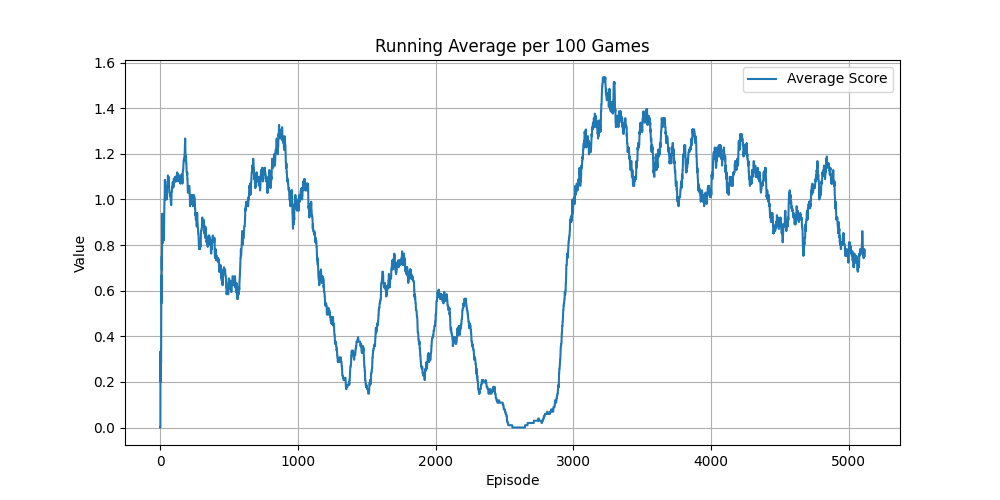

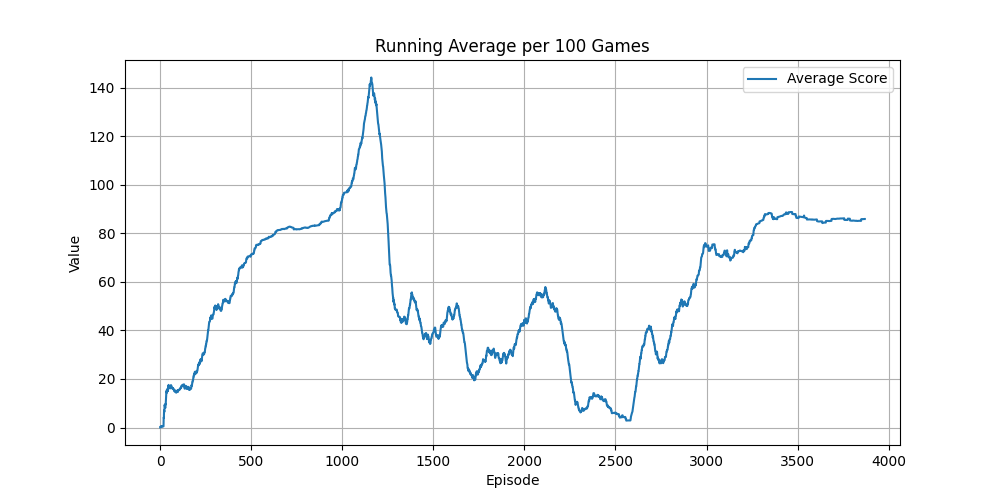

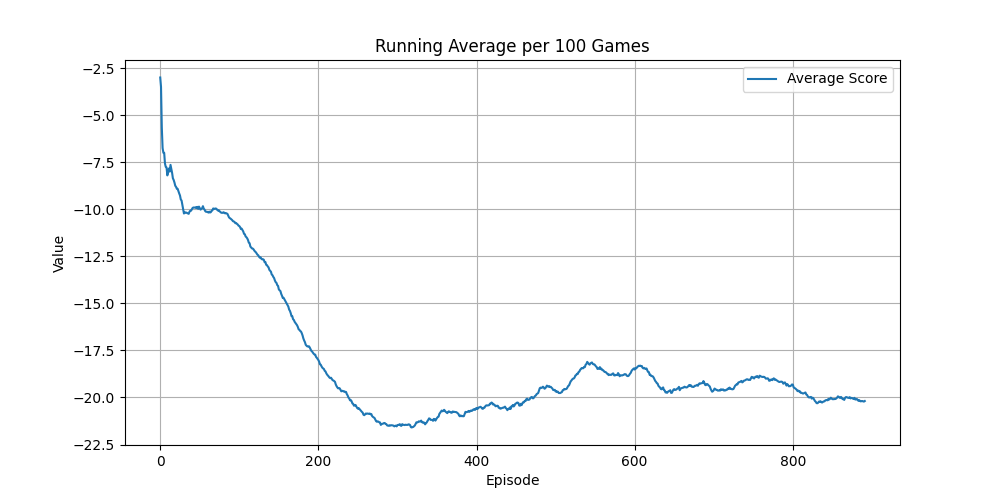

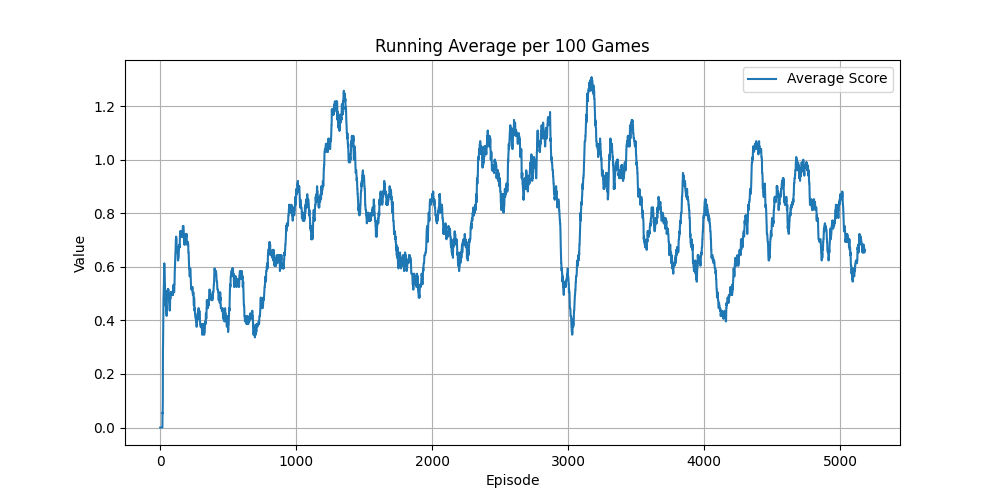

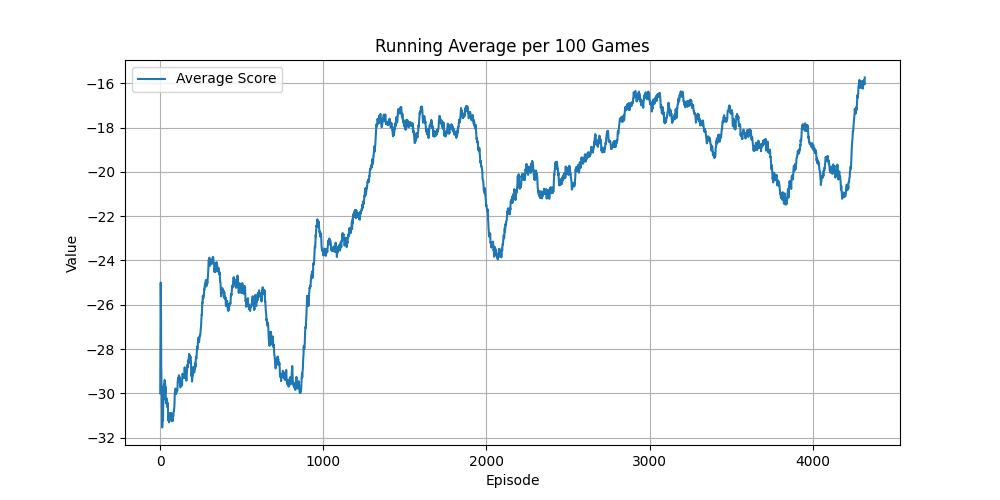

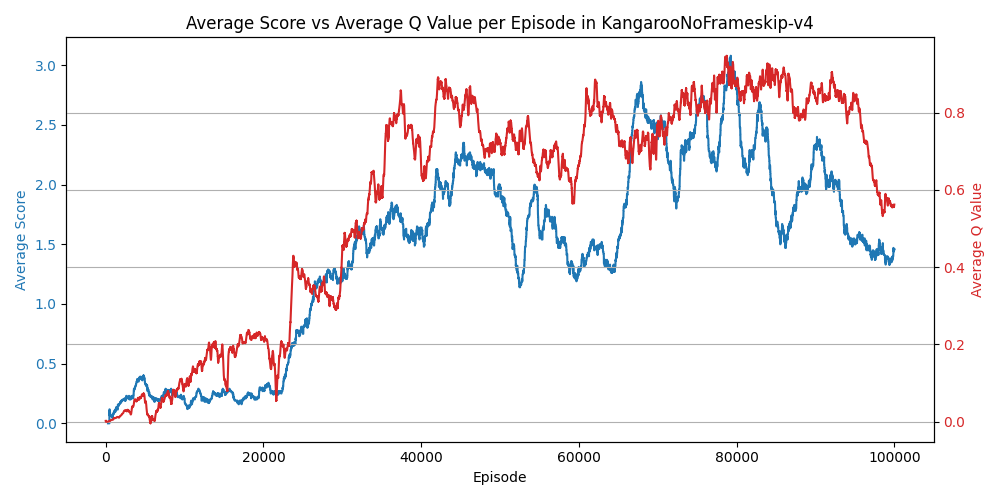

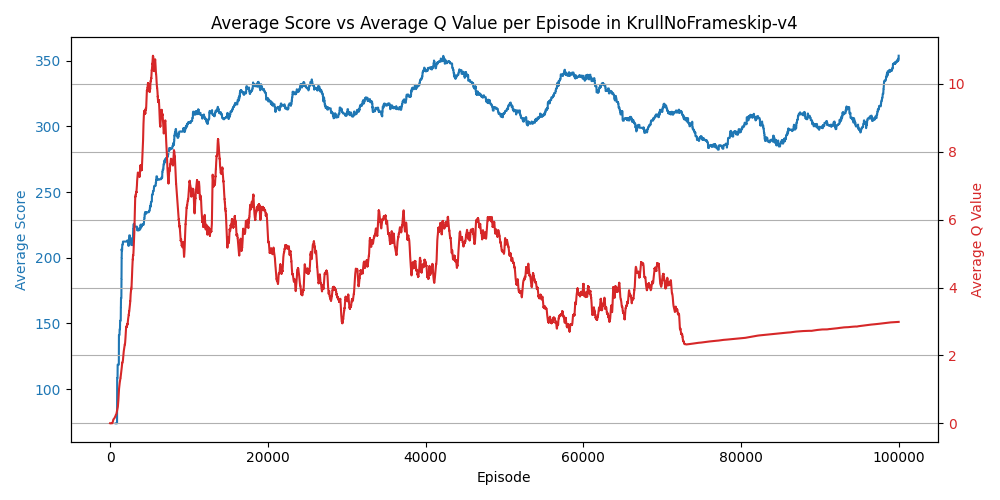

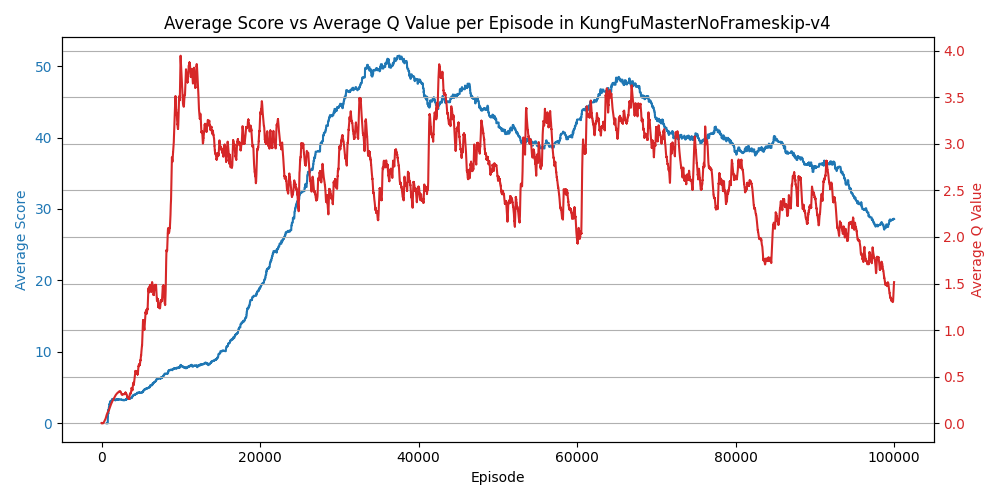

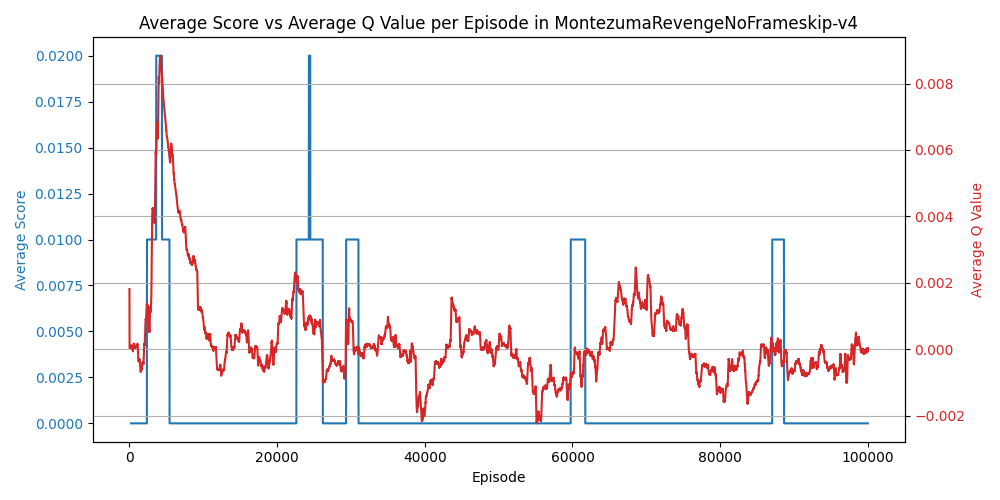

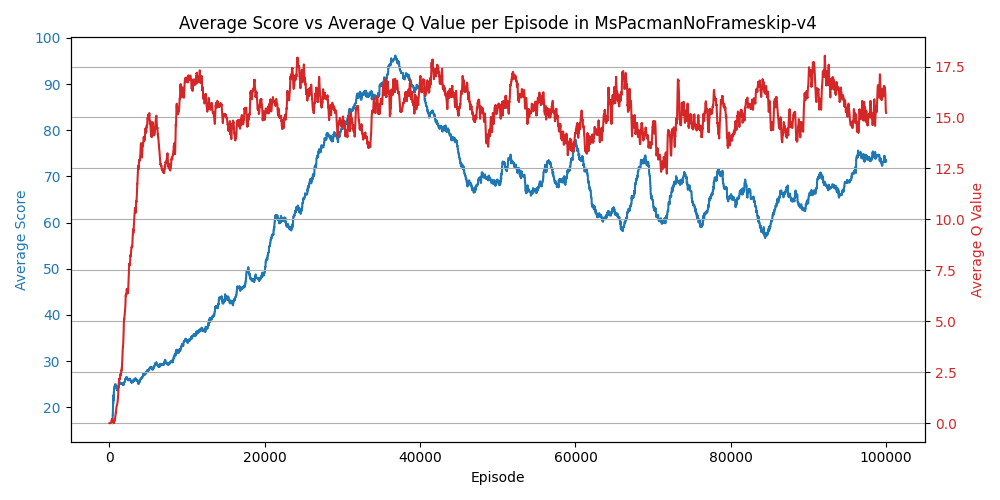

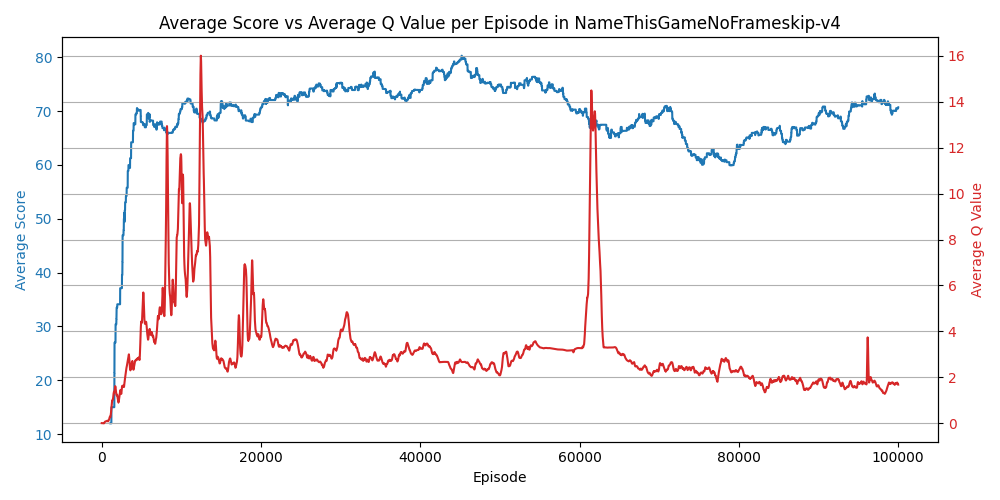

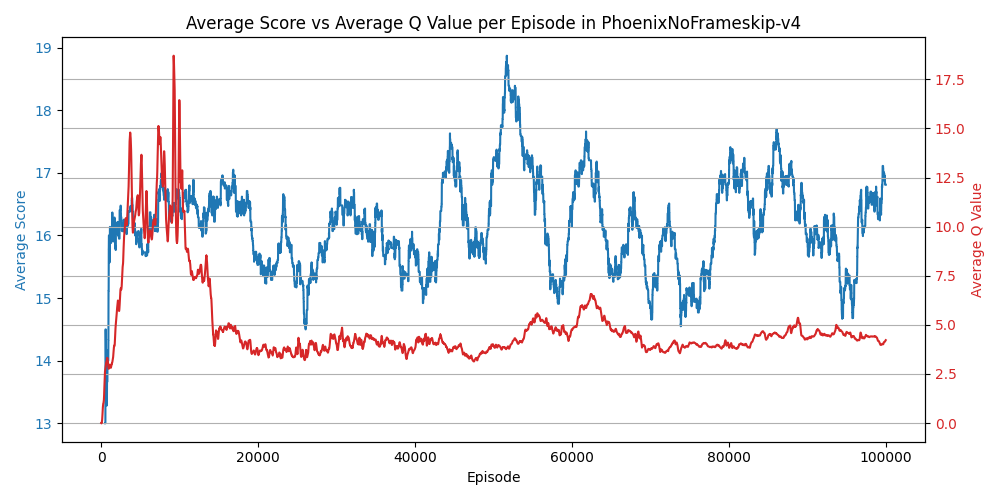

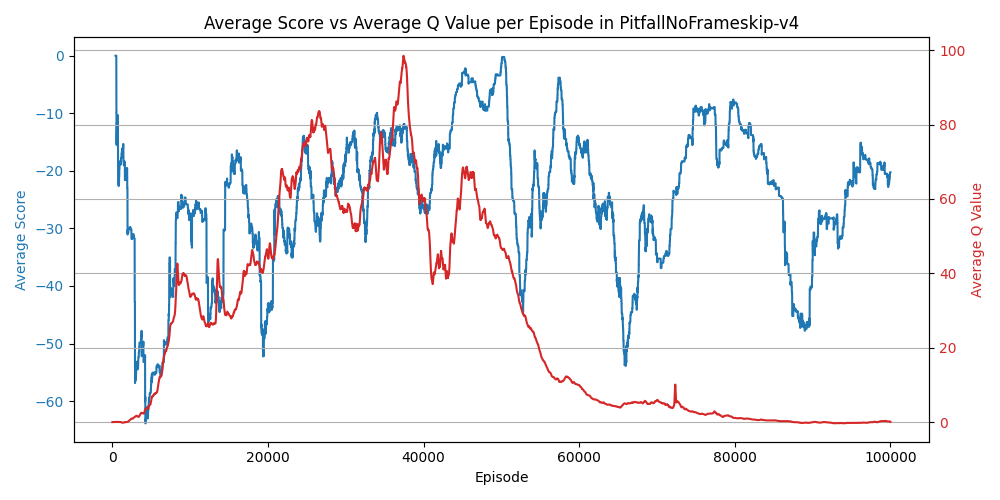

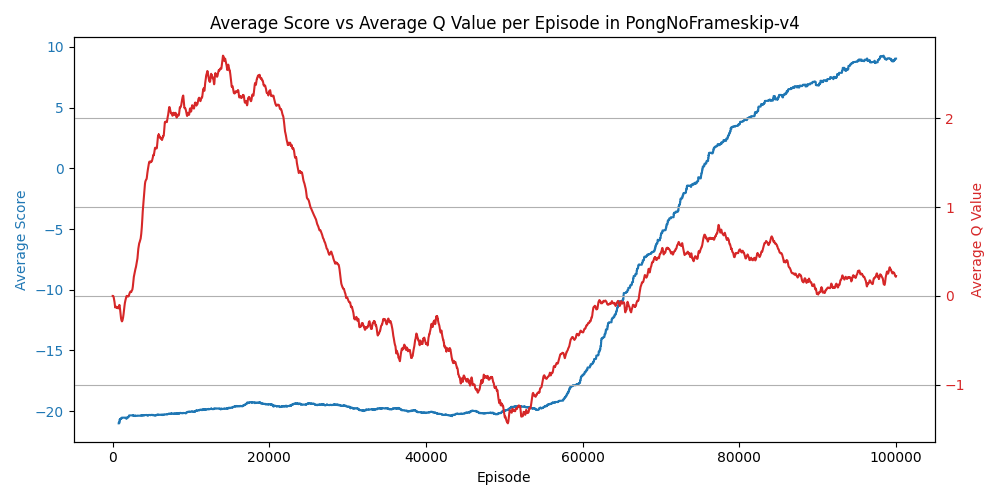

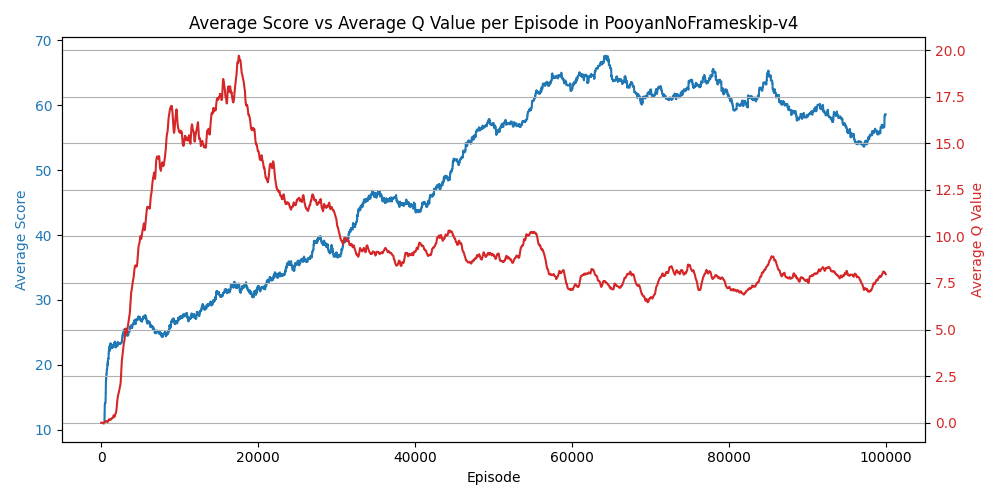

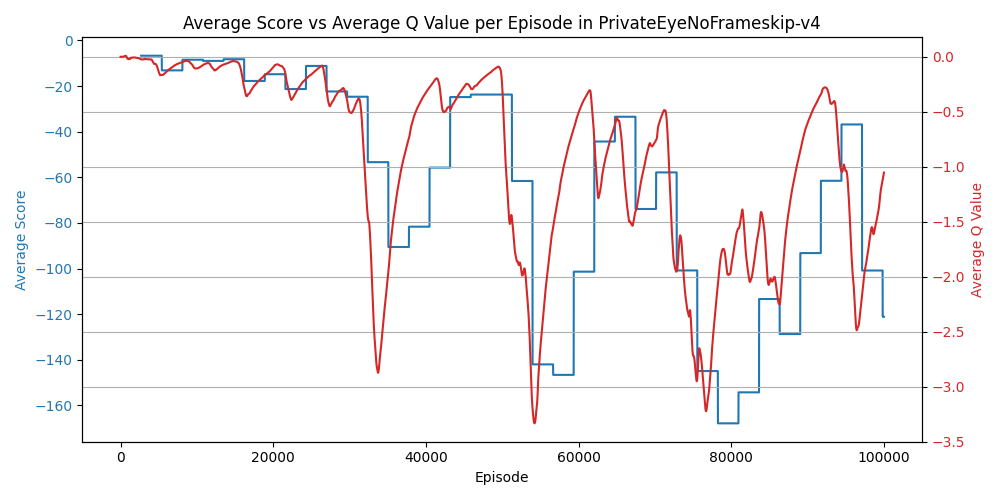

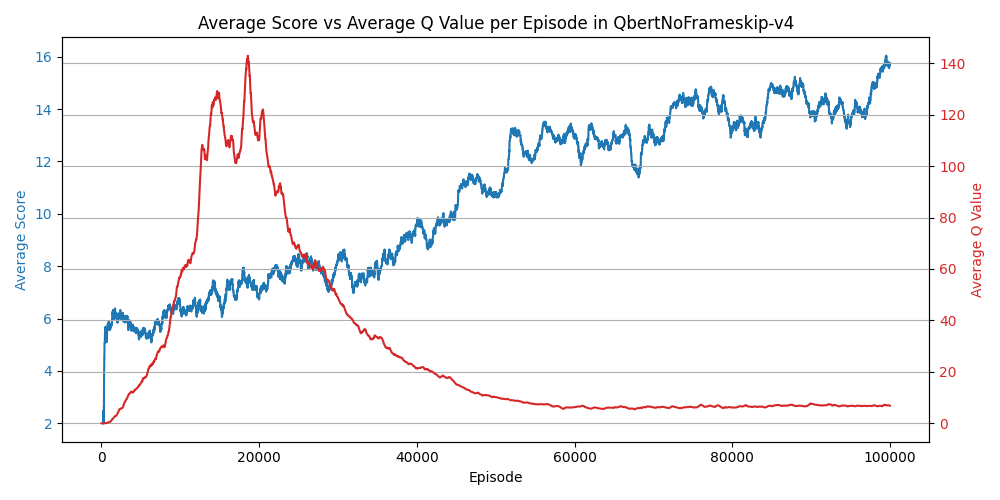

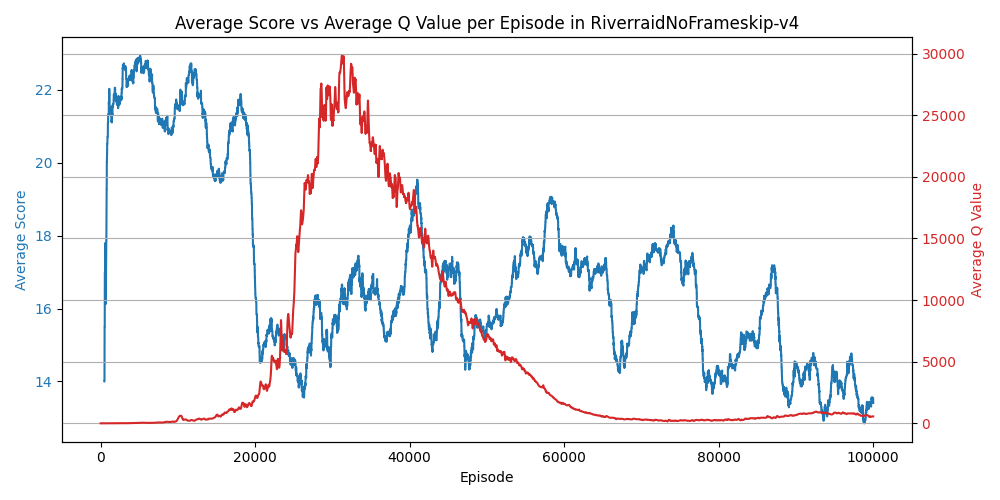

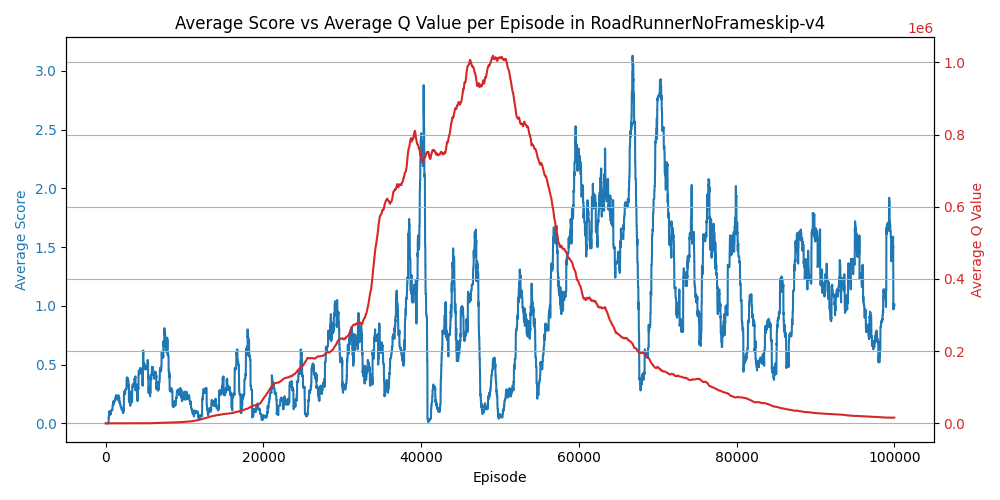

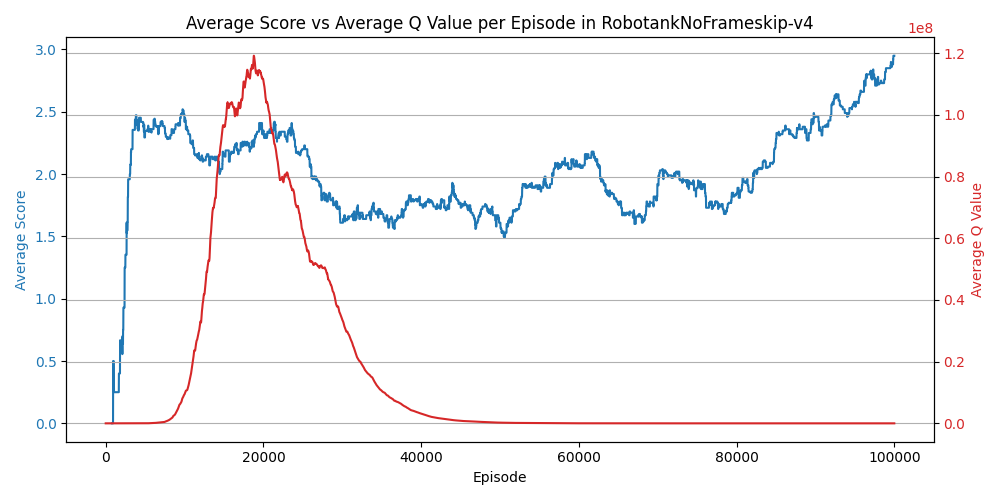

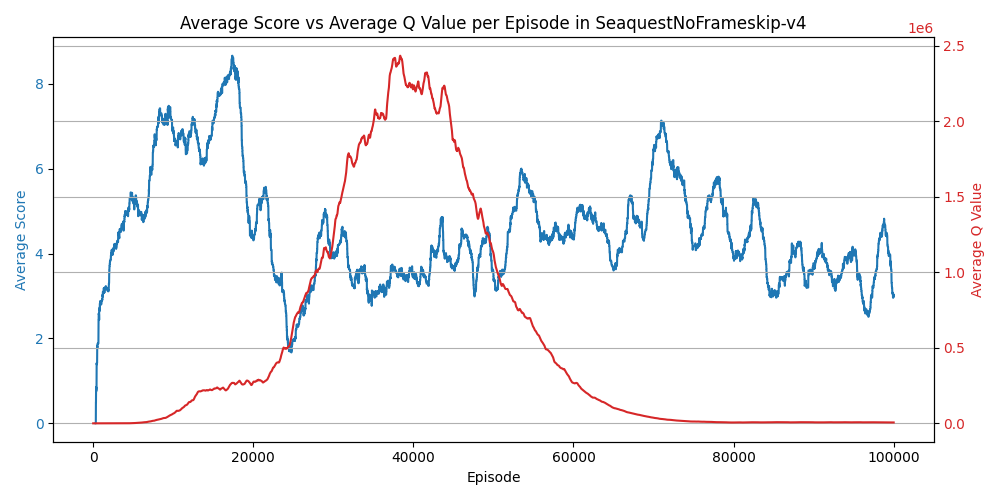

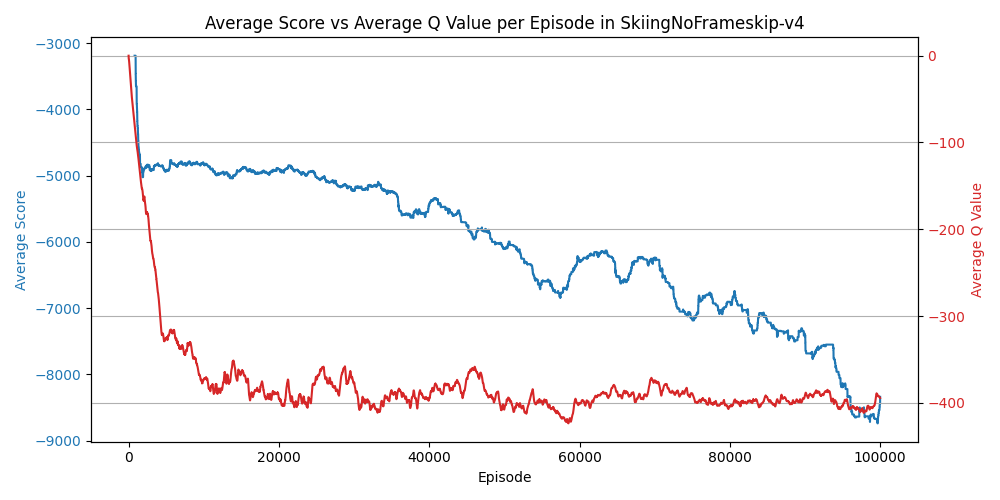

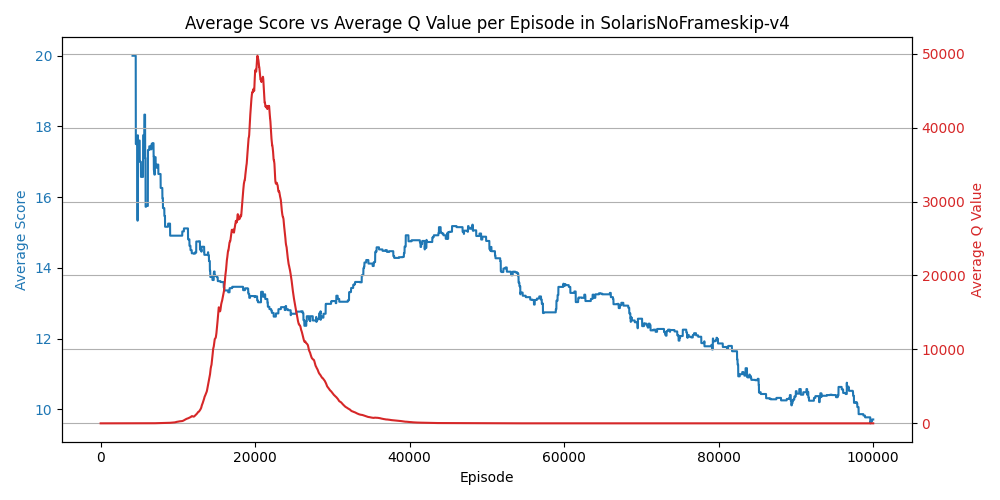

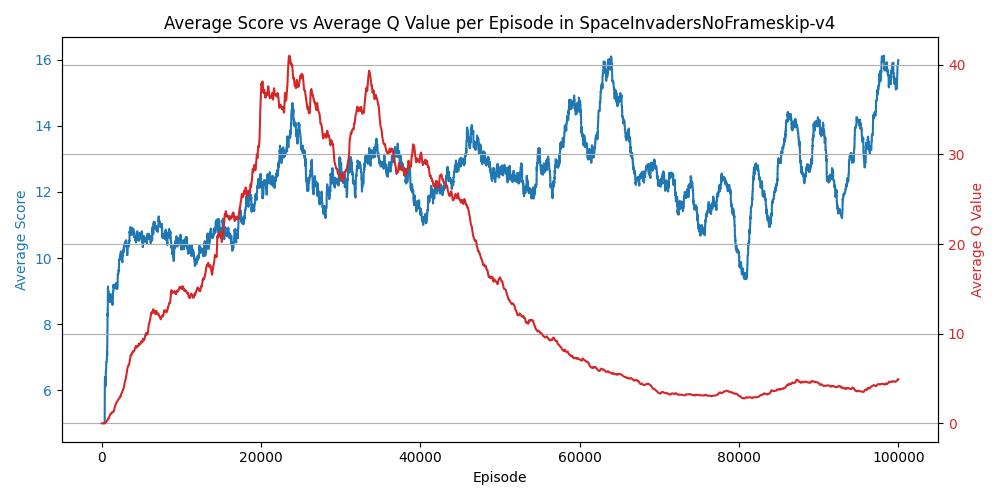

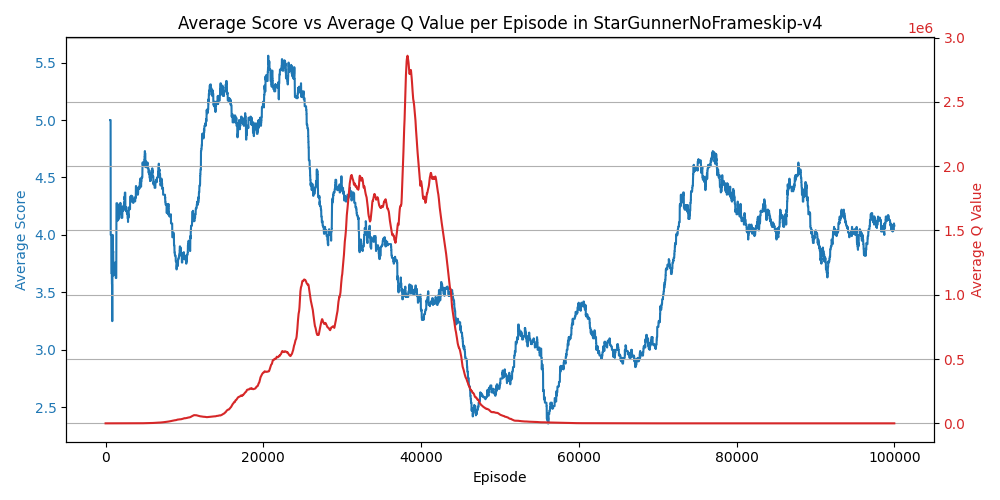

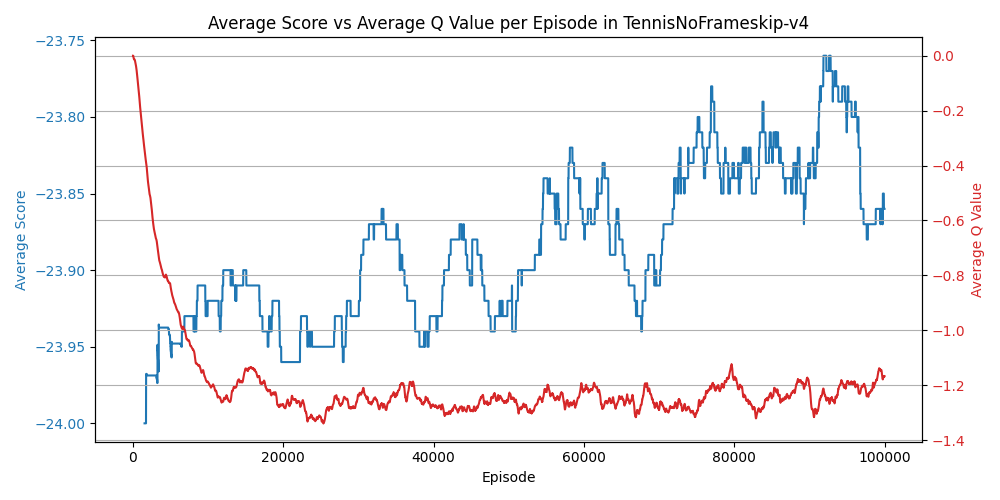

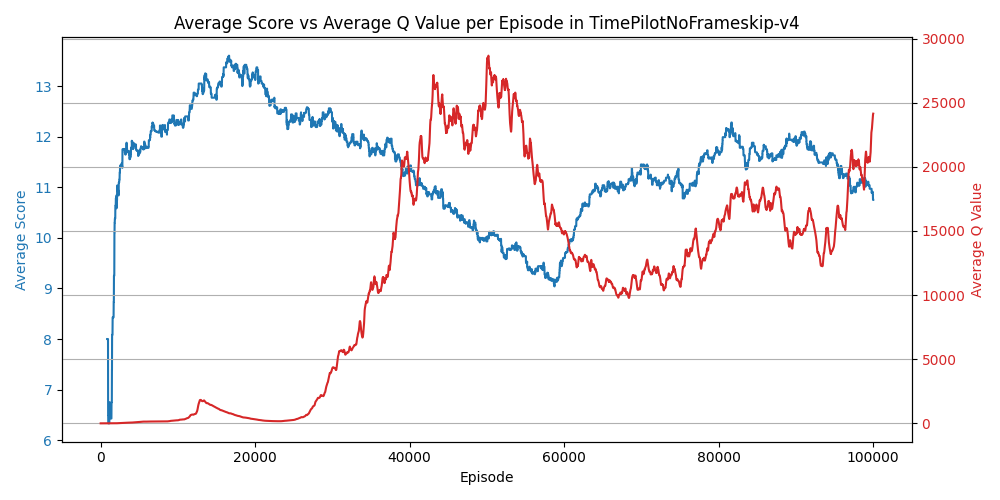

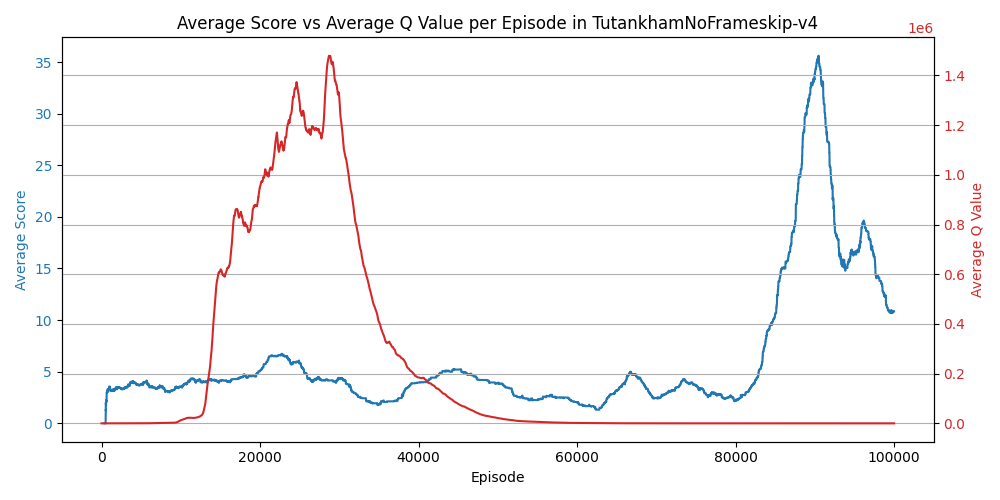

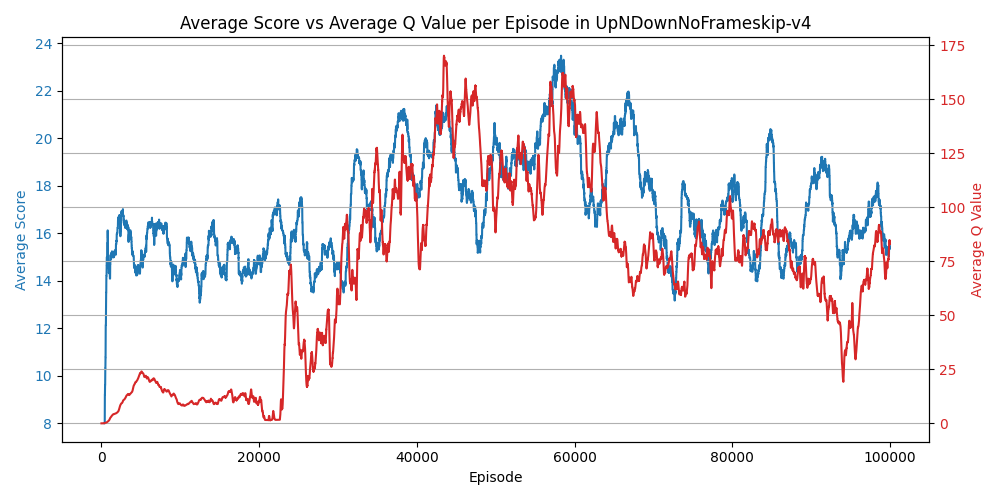

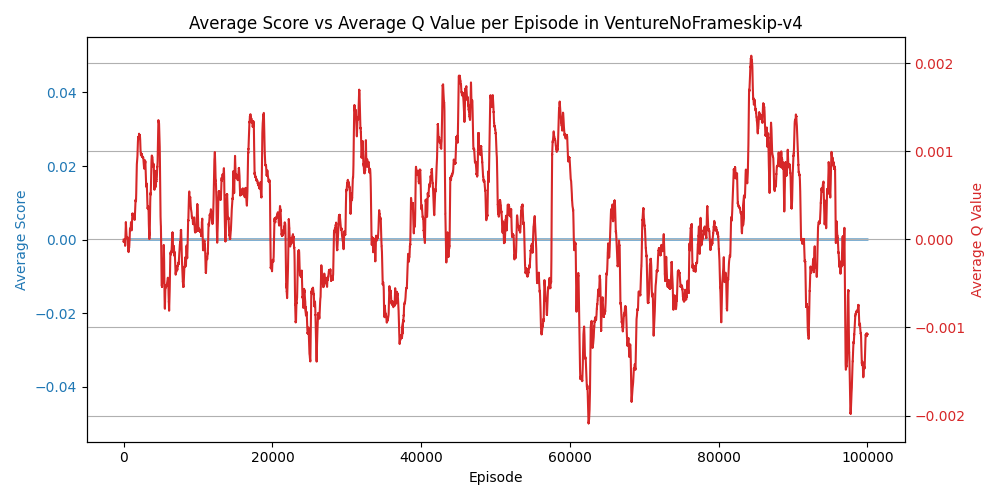

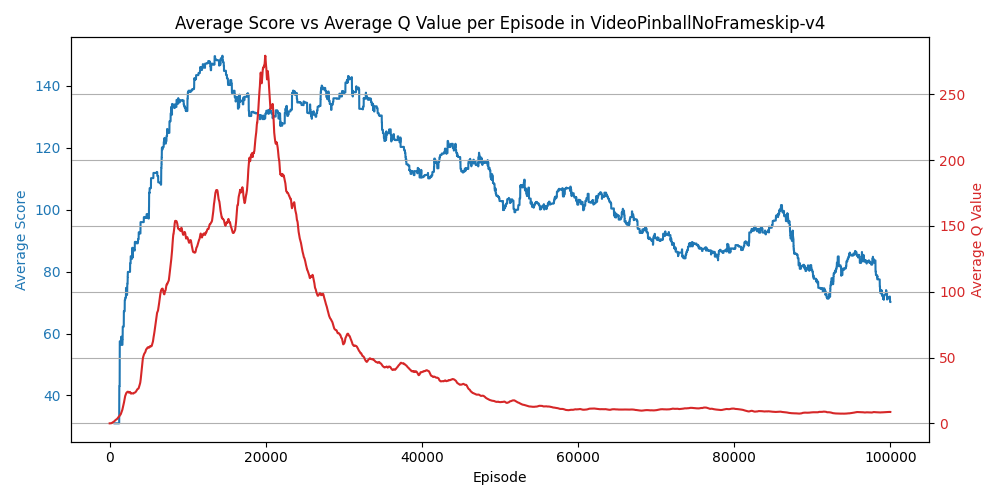

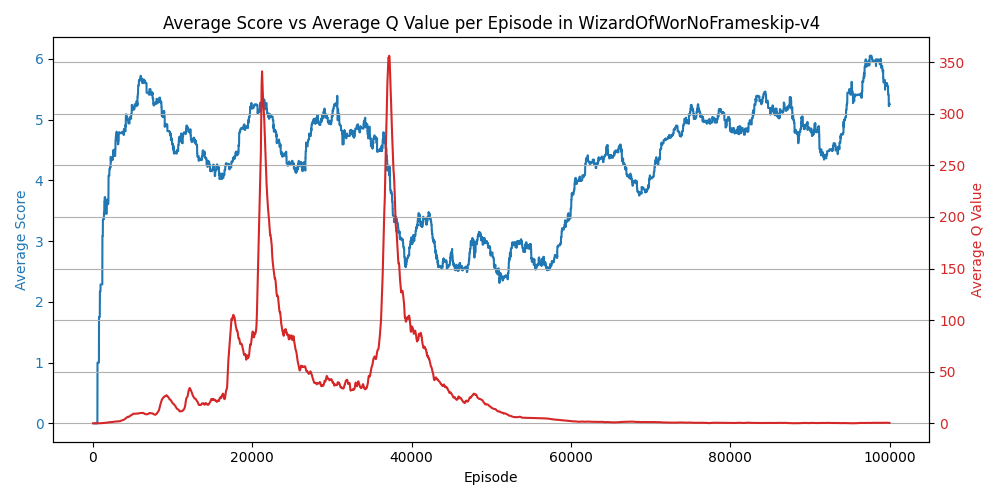

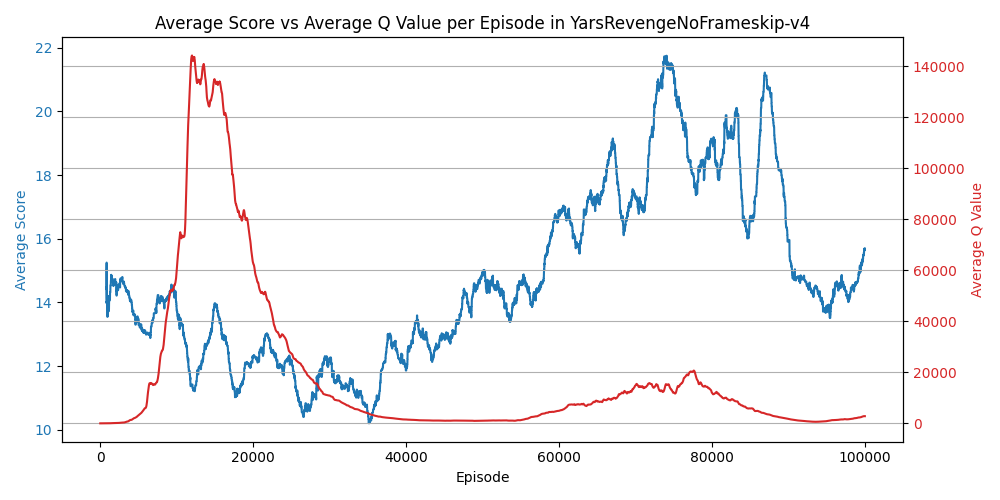

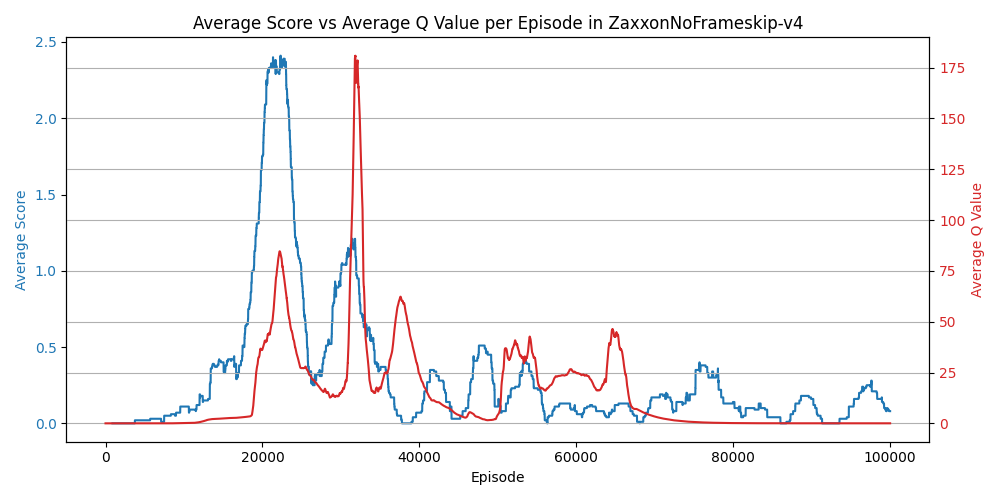

Each agent in this implementation is trained for 100,000 steps. In addition to the primary metrics tracked during training, I also began monitoring the average Q-values for a set of fixed initial states. This additional data is displayed in some of the learning plots and provides further context for evaluating the performance of the Double DQN algorithm. Tracking these average Q-values helps in understanding how the learned policy values specific states over time and can offer valuable insights into the stability and quality of the learned Q-function. Although this information appears in select plots, it complements the overall analysis by highlighting how valuable the agent considers a consistent set of scenarios throughout training, especially since early states should (usually) be fairly valuable.

|

Adventure

|

AirRaid

|

Alien

|

|

|

|

|

Amidar

|

Assault

|

Asterix

|

|

|

|

|

Asteroids

|

Atlantis

|

BankHeist

|

|

|

|

|

BattleZone

|

BeamRider

|

Berzerk

|

|

|

|

|

Bowling

|

Boxing

|

Breakout

|

|

|

|

|

Carnival

|

Centipede

|

ChopperCommand

|

|

|

|

|

CrazyClimber

|

Defender

|

DemonAttack

|

|

|

|

|

DoubleDunk

|

ElevatorAction

|

Enduro

|

|

|

|

|

FishingDerby

|

Freeway

|

Frostbite

|

|

|

|

|

Gopher

|

Gravitar

|

Hero

|

|

|

|

|

IceHockey

|

JamesBond

|

JourneyEscape

|

|

|

|

|

Kangaroo

|

Krull

|

KungFuMaster

|

|

|

|

|

MontezumaRevenge

|

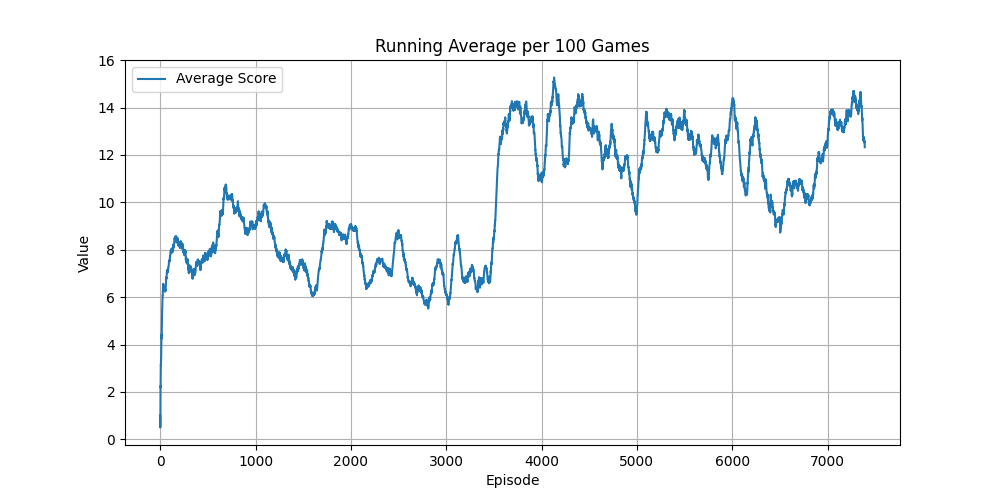

MsPacman

|

NameThisGame

|

|

|

|

|

Phoenix

|

Pitfall

|

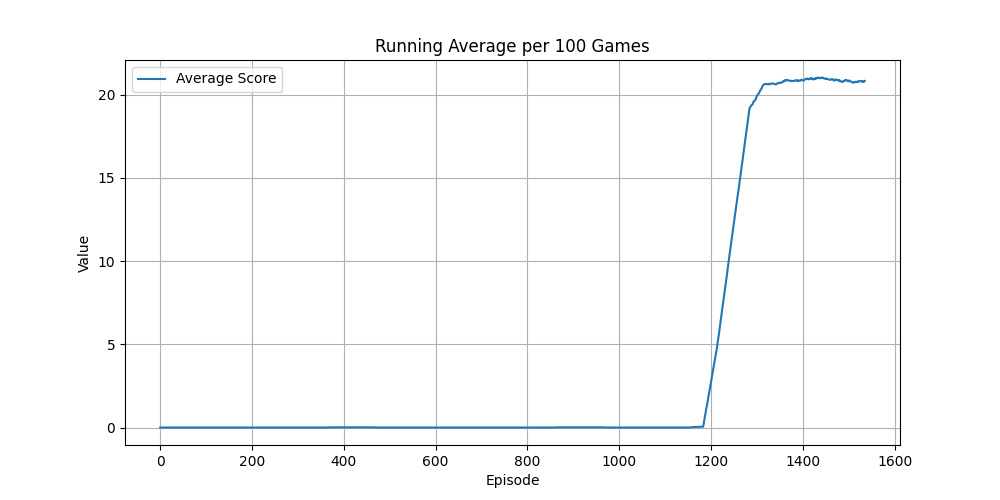

Pong

|

|

|

|

|

Pooyan

|

PrivateEye

|

Qbert

|

|

|

|

|

Riverraid

|

RoadRunner

|

Robotank

|

|

|

|

|

Seaquest

|

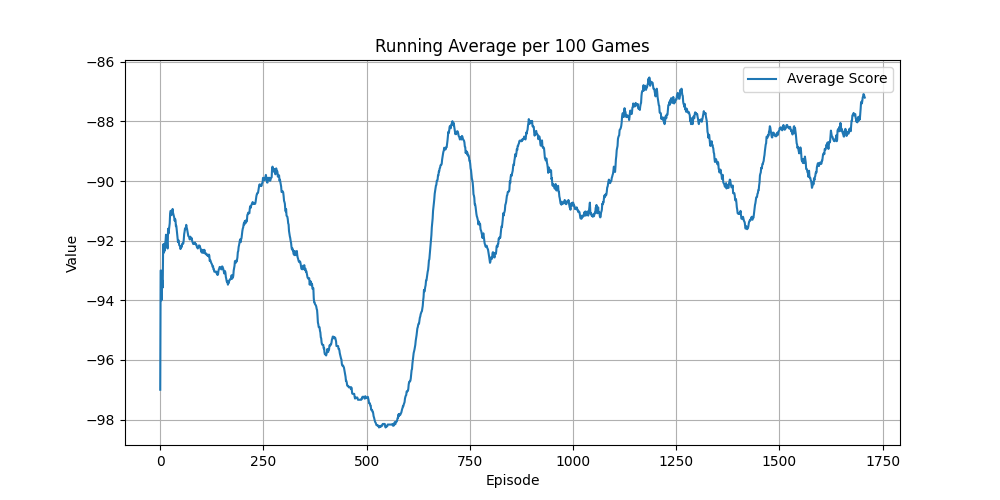

Skiing

|

Solaris

|

|

|

|

|

SpaceInvaders

|

StarGunner

|

Tennis

|

|

|

|

|

TimePilot

|

Tutankham

|

UpNDown

|

|

|

|

|

Venture

|

VideoPinball

|

WizardOfWor

|

|

|

|

|

YarsRevenge

|

Zaxxon

|

|

|

The variability in the Double DQN algorithm's performance across different Atari games highlights several nuanced challenges inherent to each environment. Understanding why some games perform poorly can provide deeper insights into the algorithm's limitations and potential areas for improvement.

-

State Space Complexity: Games like Montezuma’s Revenge and Adventure have large state spaces with many possible actions and outcomes, making it challenging for the algorithm to explore and learn effective strategies. The large state-action space requires more extensive exploration and training to converge on a good policy.

-

Action Space Complexity: Ice Hockey and Zaxxon involve high-dimensional action spaces and require continuous adjustments to control. The complexity of managing multiple simultaneous actions and interactions can overwhelm the learning process within the given training duration.

-

Delayed Rewards: Many of the mentioned games, such as Elevator Action and Solaris, feature delayed rewards where the impact of actions may not be immediately apparent. This delay in receiving feedback complicates the learning process, as the algorithm has to connect actions with rewards over longer sequences.

Games with sparse rewards and long-term dependencies between actions and outcomes are notably challenging for value-based reinforcement learning algorithms.

-

Adventure: This game requires the agent to explore a large environment with many states but provides minimal feedback. The sparse and delayed rewards, combined with the need for exploration to find keys and treasures, can hinder the learning process. The algorithm struggles to associate actions with infrequent rewards across a vast state space.

-

Elevator Action: The game involves navigating elevators to complete objectives, with varying reward structures depending on the level of the elevator. The complexity of managing elevator timing and the sparse rewards for completing objectives make it difficult for the agent to learn effective policies quickly.

-

Ice Hockey: In Ice Hockey, the fast-paced nature and continuous interaction with other players create a challenging environment. The high-dimensional action space and the need for precise coordination contribute to poor performance. The sparse scoring opportunities and the need for effective teamwork add complexity that the algorithm may struggle to master within limited training steps.

-

Montezuma’s Revenge: This game is renowned for its difficulty due to its large state space, sparse rewards, and the need for complex sequences of actions to progress through the levels. The requirement to solve puzzles and avoid traps over extended periods makes it a particularly tough environment for reinforcement learning.

-

Solaris: The game involves managing resources and navigating through space with a limited amount of information about enemy positions and threats. The sparse reward structure and the complexity of the game dynamics make it hard for the algorithm to learn an effective strategy within a limited number of steps.

-

Venture: Venture features complex game dynamics with multiple rooms and enemies. The need to navigate and engage with various threats while seeking treasures results in a challenging environment for the algorithm, with sparse rewards and long-term dependencies.

-

Zaxxon: This game requires precise control and navigation through a 3D space while managing limited resources. The combination of continuous action requirements and sparse rewards adds complexity to the learning process, leading to suboptimal performance within the training constraints.

In the original DQN paper, the authors highlighted that reinforcement learning algorithms, including DQN and its variants, often struggle with environments featuring high-dimensional spaces and sparse rewards. The Double DQN algorithm improves upon DQN by reducing overestimation bias in action value estimation, but it does not fully address the inherent challenges posed by sparse rewards and complex state-action spaces. The difficulties observed in games like Adventure and Montezuma’s Revenge underscore the limitations of current algorithms in dealing with environments requiring extensive exploration and long-term planning.

Special thanks to Phil Tabor, an excellent teacher! I highly recommend his Youtube channel.