This repository provides an example of programmatically generating Tiled-format maps in the Lua (.lua) format and using this with the STI (Simple Tiled Implementation) library. My aim is to demystify the Tiled format and to encourage others to use STI when doing procedural generation (i.e. generating random maps for roguelike or sandbox/open world games). This code doesn't get into true procedural generation, but it should serve as a decent starting point for that. It depends on the ability to pass a map table into STI directly, which was added in v0.16.0.4.

The first step is to create a table for your map:

-- create a new orthogonal map that is 64x64 tiles, each tile is 32x32 pixels

local map = {

orientation = "orthogonal",

width = 64,

height = 64,

tilewidth = 32,

tileheight = 32,

tilesets = {},

layers = {}

}I set the orientation to orthogonal (a typical top-down view). Notice that I create placeholders for tilesets and layers and setup the dimensions (in "tile" units -- the number of tiles across & number of tiles high) and also include pixel-dimensions of individual tiles.

In order for a map to display graphics, we need to reference a tileset. Each tileset image is a single image, usually a PNG, with all the tile images in it:

-- create a tileset from an image (Liberated Pixel Cup terrain_atlas.png from opengameart.org)

local tileset = {

name = "terrain_atlas",

firstgid = 1,

tilewidth = 32,

tileheight = 32,

spacing = 0,

margin = 0,

image = "terrain_atlas.png",

imagewidth = 1024,

imageheight = 1024,

tileoffset = {x = 0, y = 0},

tilecount = 1024,

tiles = {}

}

table.insert(map.tilesets, tileset)This is a 32x32 tileset from the (excellent) Liberated Pixel Cup on opengameart.org. The tilecount in my example happens to match the imagewidth and imageheight, but this isn't necessary.

Aside: in the Tiled format, I think the spacing and margin values are not completely independent of each-other. I could be wrong, but I think I recall being surprised that one includes the other.

Tiled maps are made up of layers, which are drawn in order. For this tutorial, we'll create a few layers, so we can layer things on top of each-other:

-- create a layer of the map, with the same height/width as the map

function addLayer(map, name)

local layer = {

type = "tilelayer",

name = name,

x = 0,

y = 0,

width = 64,

height = 64,

visible = true,

opacity = 1,

offsetx = 0,

offsety = 0,

properties = {},

encoding = "lua",

data = {}

}

table.insert(map.layers, layer)

return layer

end

local layer = addLayer(map, "grass")I don't think the name is strictly necessary, but it may be helpful later on. All the data here is pretty much boilerplate & matches the map data.

In the Tiled format a 0 represents an empty tile. The format seems to require that the entire layer be populated, so in some cases it's easiest to just pre-populate the whole layer with empty tiles or -- in our case -- with a grass tile:

-- populate the layer with a default tile ID

function populateLayer(layer, tile_id)

for i=1, layer.width * layer.height do

table.insert(layer.data, tile_id)

end

end

-- helper function to get the ID of a tile from the tileset using x,y coordinates

function getTileID(tileset, x, y)

local width = tileset.imagewidth / tileset.tilewidth

return x + y * width + 1 -- +1 because Tile ID 0 represents an empty tile

end

-- create a grass background layer

local grass_tile_id = getTileID(tileset, 22, 3)

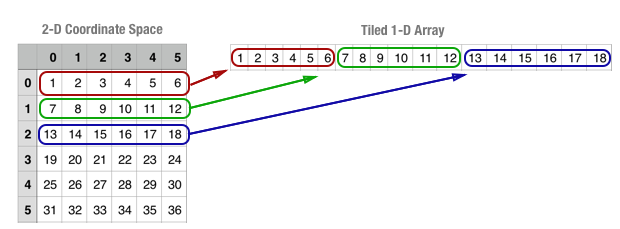

populateLayer(layer, grass_tile_id)The thing that makes this a little tricky is that the Tiled format "unrolls" 2-dimensional layer data onto a flat 1-dimensional array:

This one-dimensional array is compact and memory efficient, but it means that we can't reference tiles easily by their x,y coordinates. Instead, we need to calculate the index in the 1-D array with the formula x + y * width + 1. The + 1 is because Tile IDs are 1-based (the 0 Tile ID is reserved to represent an empty tile).

In the LPC tilesheet, there are path tiles from coordinates (18,2) to (20,4). We want a path that stretches horizontally across our map, so we'll just take the middle column of path tiles (19,2) to (19,4):

-- helper function to set a tile in the layer based on x,y coordinates

function setTile(layer, x, y, tile_id)

layer.data[x + y * layer.width + 1] = tile_id -- +1 because Tile ID 0 represents an empty tile

end

-- create a layer for the path

local path_layer = addLayer(map, "path")

populateLayer(path_layer, 0)

for x=0, path_layer.width - 1 do

setTile(path_layer, x, 5, getTileID(tileset, 19, 2))

setTile(path_layer, x, 6, getTileID(tileset, 19, 3))

setTile(path_layer, x, 7, getTileID(tileset, 19, 4))

endNote that setTile() uses the same x + y * width + 1 formula to convert from (x,y) space to Tiled's 1-dimensional array (+ 1 because Lua arrays are 1-based).

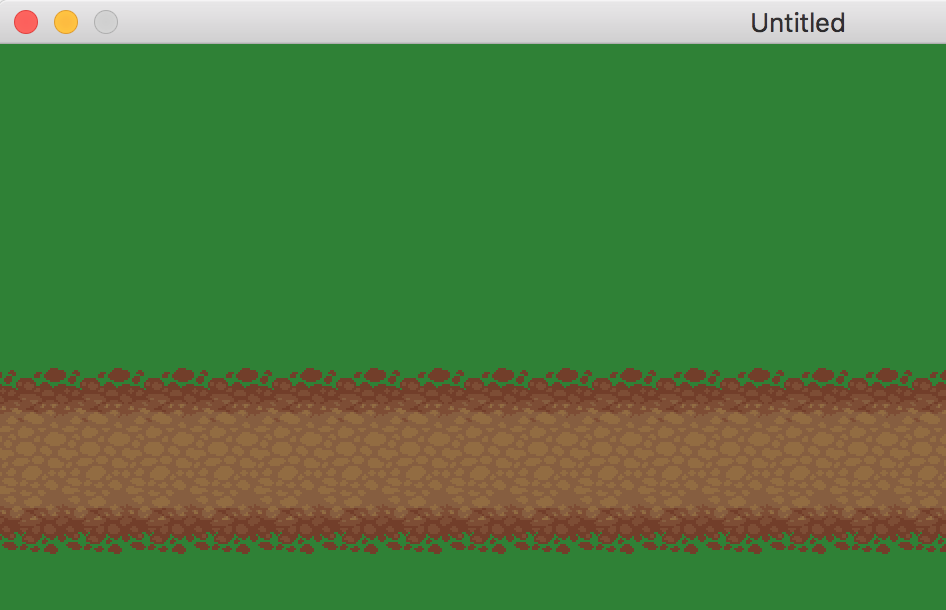

Add in some LÖVE and STI boilerplate (you can find this in the main.lua file), and we can see our path:

In the LPC tilesheet, there is a tree from the top-left coordinate of (30, 0) to the bottom-right coordinate of (31, 4), assuming a coordinate system that starts at (0, 0). Here, we add each of the 8 tree tiles to the layer:

-- create a layer for objects like trees

local objects_layer = addLayer(map, "objects")

populateLayer(objects_layer, 0)

setTile(objects_layer, 1, 1, getTileID(tileset, 30, 0))

setTile(objects_layer, 2, 1, getTileID(tileset, 31, 0))

setTile(objects_layer, 1, 2, getTileID(tileset, 30, 1))

setTile(objects_layer, 2, 2, getTileID(tileset, 31, 1))

setTile(objects_layer, 1, 3, getTileID(tileset, 30, 2))

setTile(objects_layer, 2, 3, getTileID(tileset, 31, 2))

setTile(objects_layer, 1, 4, getTileID(tileset, 30, 3))

setTile(objects_layer, 2, 4, getTileID(tileset, 31, 3))

setTile(objects_layer, 1, 5, getTileID(tileset, 30, 4))

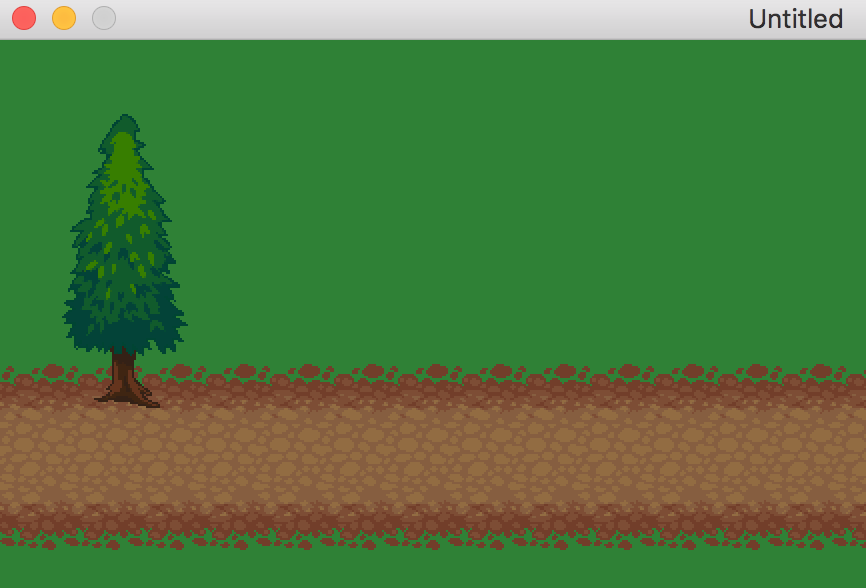

setTile(objects_layer, 2, 5, getTileID(tileset, 31, 4))Here's an updated screenshot with the tree:

I hope the above example made the Tiled Lua format clearer and more approachable. While it is certainly possible to ignore this format and the STI library and to instead create your own table format for procedurally-generated terrain, there are advantages to using the STI library, since it has become a bit of a standard in the LÖVE community and many libraries, tutorials and example code use it or interoperate well with it.