This project implements the 2016 paper End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars in which Bojarski et al. describe a convolutional neural network architecture used to infer vehicle control inputs given a forward facing vehicle camera stream. I apply the techniques in this paper to a driving simulation game : a player inputs controls to the simulator's virtual vehicle, and the mapping between the scene in front of the car and the player's controls is modeled by a neural network to "autonomously drive" the virtual car. Once trained, this neural network implementation drives a virtual car for dozens of laps around a virtual track with no human intervention.

This procedure was tested on Ubuntu 16.04 (Xenial Xerus) and Mac OS X 10.11.6 (El Capitan). GPU-accelerated training is supported on Ubuntu only. Prerequisites: Install Python package dependencies using my instructions. Then, activate the environment:

source activate deep-learning

Acquiring the driving simulator and example dataset with camera stream images and steering control inputs by a human player:

wget https://d17h27t6h515a5.cloudfront.net/topher/2017/February/58ae46bb_linux-sim/linux-sim.zip # linux version of simulator

unzip linux-sim.zip

rm -rf linux-sim.zip

wget -O udacity_dataset.tar.gz "https://www.dropbox.com/s/s4q0y0zq8xrxopi/udacity_dataset.tar.gz?dl=1" # example dataset

tar -xvzf udacity_dataset.tar.gz

rm -rf udacity_dataset.tar.gz

Optional, but recommended on Ubuntu: Install support for NVIDIA GPU acceleration with CUDA v8.0 and cuDNN v5.1:

wget -O cuda-repo-ubuntu1604-8-0-local-ga2_8.0.61-1_amd64.deb "https://www.dropbox.com/s/08ufs95pw94gu37/cuda-repo-ubuntu1604-8-0-local-ga2_8.0.61-1_amd64.deb?dl=1"

sudo dpkg -i cuda-repo-ubuntu1604-8-0-local-ga2_8.0.61-1_amd64.deb

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install cuda

wget -O cudnn-8.0-linux-x64-v5.1.tgz "https://www.dropbox.com/s/9uah11bwtsx5fwl/cudnn-8.0-linux-x64-v5.1.tgz?dl=1"

tar -xvzf cudnn-8.0-linux-x64-v5.1.tgz

cd cuda/lib64

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=`pwd`:$LD_LIBRARY_PATH # consider adding this to your ~/.bashrc

cd ..

export CUDA_HOME=`pwd` # consider adding this to your ~/.bashrc

sudo apt-get install libcupti-dev

pip install --ignore-installed --upgrade https://storage.googleapis.com/tensorflow/linux/gpu/tensorflow_gpu-1.1.0-cp35-cp35m-linux_x86_64.whl

This file is the core of this project. Use it to train the NVIDIA model on a driving dataset. Use python model.py -h

to see documentation information. Example command:

python model.py -d udacity_dataset -m model.h5 -c 3000

The program assumes the following:

- The required

-dargument is a path to the dataset directory.- The dataset directory contains a single .csv file with a driving log along with many .jpg images recorded from the player driving sequence associated with the log.

- The image names in the driving log match the images names in the dataset directory. I.e. image names such as

dir/IMG/center_2016_12_01_13_30_48_287.jpgshould be replaced in the driving log with simplycenter_2016_12_01_13_30_48_287.jpg. Use scripts such asscripts/combine_datasets.pyandscripts/fix_filenames.pyto prepare your dataset to work with this pipeline. - It's recommened that you start with the example dataset provided in the installation instructions.

- The required

-margument is the name of the Keras model to export. - The optional

-cargument is the CPU batch size i.e. the number of measurement groups that will fit in system RAM on your machine. The default value of 1000 should fit comfortably in a 16GB RAM machine. - The optional

-gargument is the GPU batch size i.e. the number of training images and training labels that will fit in VRAM on your machine. The default value of 512 should fit comfortable in a 6GB VRAM machine. - The optional

-rargument specifies whether or not to randomize the row order of the driving log.

In case you do not want or are not able to train a neural network on your machine, you can download my pre-trained model which successfully drives autonomously around a virtual track:

wget -O model.h5 "https://www.dropbox.com/s/l9f4gqb596rnjst/model.h5?dl=1"

Use drive.py in conjunction with the simulator to autonomously drive a virtual car according to a neural network model.

Usage of drive.py requires you to have saved the trained model as an h5 file, e.g. model.h5. This type of file is created

by running model.py as described above. Once the model has been saved, it can be used with drive.py using this commands:

python drive.py model.h5

This command prepares causes the driving program to start and wait for the simulator to be initialized. On Linux, initialize the simulator with the following (procedure is very similar on Mac):

cd linux_sim

./linux_sim.x86_64

Select the lowest resolution and fastest graphical settings. Afterward select "autonomous mode" followed by the desired track. The car will now drive on its own. This procedure loads the trained model and uses the model to make predictions on individual images in real-time and send the predicted angle back to the simulator server via a websocket connection.

python drive.py model.h5 run1

The fourth argument, run1, is the directory in which to save the images seen by the agent. If the directory already exists, it'll be overwritten. The

image file name is a timestamp of when the image was seen. This information is used by video.py to create a chronological video of the agent driving.

The following command...

python video.py run1

...creates a video based on images found in the run1 directory. The name of the video will be the name of the directory

followed by '.mp4', so, in this case the video will be run1.mp4. Optionally, one can specify the FPS (frames per second) of the video

like so:

python video.py run1 --fps 48

This will run the video at 48 FPS. The default FPS is 60.

A human player plays the simulation game manually and records game footage that is later used to train a neural network. On one of each six animation frames of the simulator (10 Hz), three virtual cameras on the front of the car capture 3 images into the dataset: a center image, a left side image, and a right side image. Over the course of gameplay, tens of thousands of (image, steering input) data pairs are recorded.

| Left Camera View | Center Camera View | Right Camera View |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

At each moment in which player data is recorded, a single steering input is recorded. This steering input is thus associated with three images: a left image, a center image, and a right image. However at inference time, a single steering input is inferred by the neural network given a single center view image. Thus, to make the left and right view images useful for neural network training, the steering input is increased by 0.2 degrees for a left image and decreased by 0.2 degrees for a right image.

Furthermore, the network must learn how to react to all kinds of turns. Unfortunately, a racing track will provide mostly left turns as examples because the car travels along the track counterclockwise. Thus the dataset is augmented with horizontally flipped versions of the three types of input images described in the previous paragraph as shown below:

In total, for each moment in which player training data is collected, 6 (image, steering input) pairs are added as training examples for the neural network. The next preprocessing step is cropping to remove parts of the scene that do not contain the road and normalization to ensure numerical stability during weight value optimization. The final preprocessing step is randomization: the dataset is shuffled such that the order of the (image, steering input) pairs is random.

This project uses a Keras implementation of the model described by Bojarski et al in the paper End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars which uses the convolutional architecture depicted in the following figure from the paper:

Rectified linear units are used as activation functions for each layer. Unlike the paper, this project performs preprocessing (including normalization) in batches outside of the training procedure. Thus, preprocessing is not GPU accelerated, but also does not have to be re-performed each time the network is retrained. For real-time performance applications, the GPU implementation of any preprocessing steps should be considered to increase the inference framerate.

The example dataset contains over 24,000 example camera views. With preprocessing, this total rises to over 48,000 training examples. This project implements user-configurable batch-based training such that the dataset is trained in batches big enough to fit in CPU and GPU memory. The neural network is trained using Keras implementation of the Adam optimizer and the mean squared error loss function. Before training and batching begins, the dataset is divided into training and validation sets: 20% of the dataset is reserved for validation. Using an NVIDIA GTX 1060 GPU and Intel Pentium G4600 CPU, training the entire dataset in batches for 15 epochs per batch takes 10 minutes.

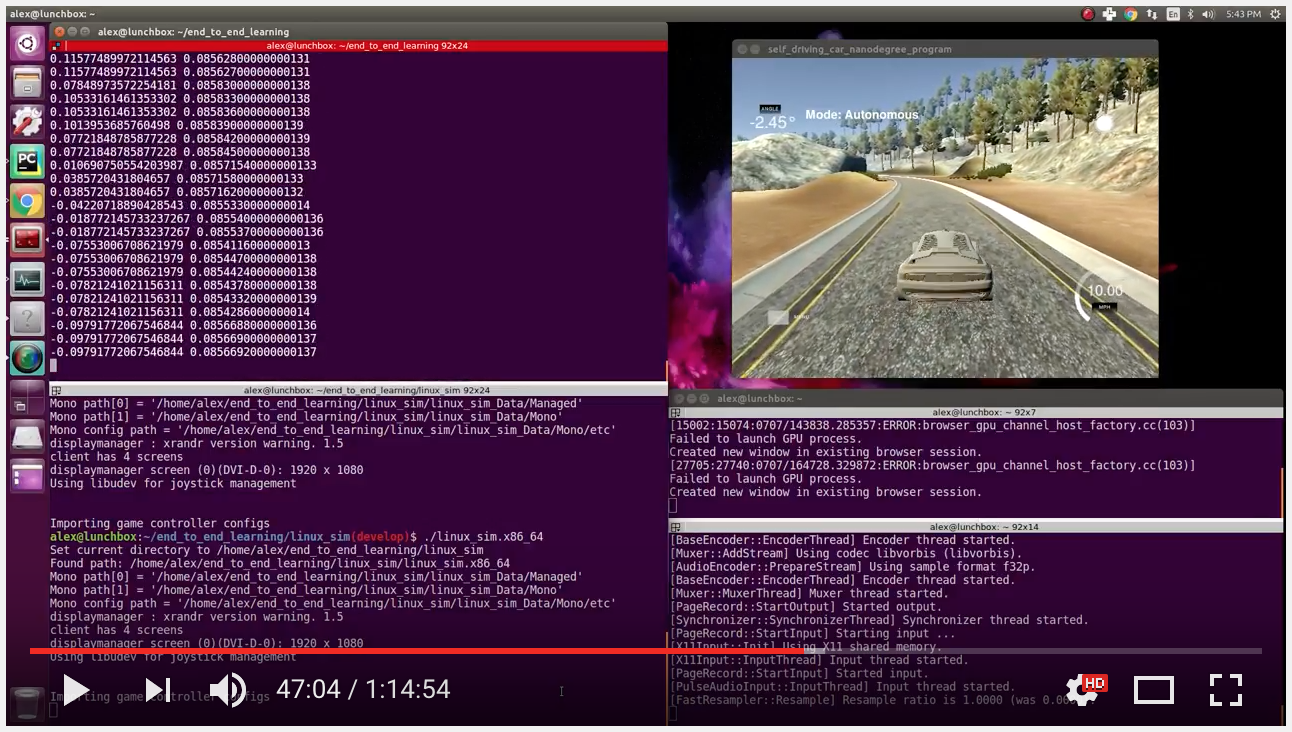

This neural network implementation successfully drives a virtual car for dozens of laps around a virtual track with no human intervention. Over 1 hour of video evidence is provided below:

| Autonomous Mode Full Screen Capture | Autonomous Mode FPV Feed |

|---|---|

|

|

As is to be expected, obstacles and terrain not encountered in the training set cause issues if they appear in the test set. When the neural network's performance was tested on a track with a differently patterned driving surface, different surrounding flora, and different obstacles, the network's decisions caused collisions and poor dirving performance. The folowing figure illustrates a collision with an obstacle type not encountered in the training set that appears in a different testing track:

Although the driving performance observed in the videos is encouraging, much work remains to create a complete autonomous agent for simulated driving. Future work on this project will be aimed at improving the generalization capabilities of this technique such that the system will be able to competently drive in diverse simulated environments. Two ways to improve generalization are to (1) augment the training dataset with more varied data and (2) to increase the sophistication of the algorithm applied to this problem. Method (1) can be implemented by carrying out more human-controlled simulated driving runs to record more training data. This method is limited in that it scales poorly because it requires long hours of manual work. Method (2) can be implemented by either (a) researching improved network architectures for end-to-end learning and (b) attempting improved preprocessing techniques not discussed in the cited paper. Option (b) could be approached by experimenting with preprocessing techniques that focus on the general task at hand: staying between the lines defined by the border between driving surface and non-driving surface. One possible method would be to use gradient images or images processed with Canny edge detection or line segment detectors as inputs to the neural network as opposed to normalized color images. The potential drawback of this option is that it introduces the issue of manually tuning more hyperparameters for any such edge or line detection algorithm.